![]()

Chapter 1

A HILLSIDE IN SOUTH AFRICA

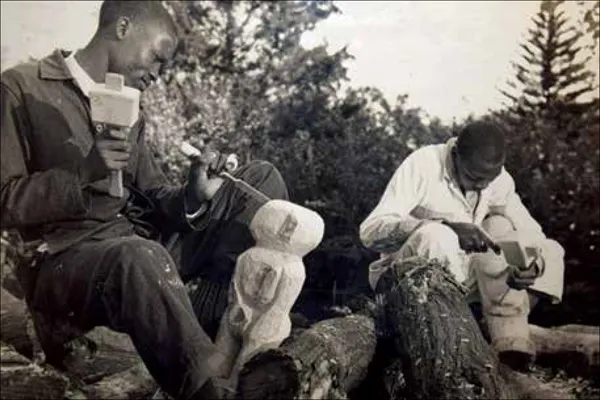

FOR MOST, the greatest challenge was the lack of materials. The syllabus called for students to weave with grass, but in many areas, no suitable grass existed; teachers reported using wool instead. When the lack of paint demanded similar improvisation, “we are using wet chalk and crayons.”1 The syllabus was unrelenting, no matter whether teachers taught in rural schools with ample stone and wood or in denuded urban areas where “there is no wood because the school is right in the Location.”2 Teachers were forced to find creative solutions to their particular experiences of material want, and they eagerly exchanged advice and suggestions. “Wood for sculpture can often be obtained free of charge from municipalities when trees such as Jacaranda, Silver Oak or Syringa have to be pruned or cut down,” one teacher reported, “John Ngcobo succeeded in getting some wood in this way in Pietermaritzburg.”3 Vivian Bopape frequented waste yards outside factories and in industrial areas; her quests were often rewarded with spoiled newsprint, broken glass, and torn sponges—all of which proved useful in her lessons.4 Material want affected teachers’ own art practices as well. Winston Radebe was a talented draftsman, but he lacked the money to buy conté crayons or charcoals. So he drew with shoe polish—Nugget brand, black and brown—and proudly enclosed a sample for his art teacher.5 Correspondence about materials dominated the pages of the art teachers’ newsletter from its initial publication in 1961. Lack was the “major enemy” of Ndaleni graduates, and its defeat drew the community of teachers, students, and artists together.6

Figure 1.1 A man in black and brown shoe polish, drawing by Winston Radebe, 1965, photograph by the author

Between the early 1950s and the early 1980s, South Africa’s Department of Bantu Education ran a school for the training of specialist arts and crafts teachers at Indaleni, outside Richmond in the Natal Midlands. Over those decades, nearly a thousand students attended the course, which qualified them to teach the department’s arts and crafts syllabus in apartheid South Africa’s schools. As we have seen, long before the advent of the policy of Bantu Education, syllabi for Africans had mandated that black students engage in what was variously called art, handwork, industrial education, craftwork, or arts and crafts while enrolled in government-funded schools. This took on a new urgency in the 1950s, when arts and crafts featured in the apartheid government’s efforts to preserve the absolute distinction between African (or “Bantu”) and European education. In the years leading up to the adoption of the Bantu Education Act in 1953, apartheid bureaucrats and theorists considered how best to ensure that the syllabus promoted difference—and in the years that followed, qualified teachers went to Ndaleni to study the activities called for in the Bantu Education syllabus.

At Ndaleni, they studied grasswork, beadwork, bonework, painting, drawing, wood carving, and claywork, among other subjects; they also developed their own art practice and gained a working knowledge of art history. Paid for with government bursaries, the art program was a two-year course through the 1950s and was then reduced to a one-year program from the 1960s until the course’s end in 1981. In return for the government bursary and a pay increase upon completing the course, Ndaleni students agreed to teach art in the apartheid government’s African schools. Close to a thousand graduated, about one hundred failed to complete the course, and nearly two thousand more were turned away because of a lack of space.7

That only one-third of applicants were admitted to the Ndaleni program indicates its appeal. A year at Indaleni (the former mission station as opposed to the art school, which did not use the locative prefix) was a year nestled in the Midlands, painting, sculpting, drawing, learning. The vast majority of Ndaleni students were already working teachers, so a year at Ndaleni also meant time away from their typically underfunded and overcrowded schools; it also meant a year without pay, being confined to shabby mission accommodations, and for older students being away from their families. Many considered themselves artists, even if society did not recognize them as such, and although it was not an art school in the strictest sense, Ndaleni was one of a very few places where black South Africans could study and develop their art.8 Yet attaining an Ndaleni certificate did not promise a much easier life. The same problems awaited graduates—more and more students, dilapidated working conditions, a pervasive lack of materials, and an even more pervasive lack of appreciation.

Figure 1.2 Students carving, late 1960s, photographer unknown, Ndaleni Scrapbook 4, with the permission of the Campbell Collections of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (hereafter cited as CC)

For many, it was worth it. Teaching art in Bantu Education schools could be rewarding, as Elijah Zwane wrote in the early 1960s. “Wishing to see what I had in my class, I introduced modeling in clay and picture painting, and the work of the pupils struck me with wonder,” he gushed. It was marvelous to “see what talents remain buried in the nerves of an African child.”9 A decade later, Mercy Ghu was similarly enthusiastic: “[The students’] imagination is fairly wide when it comes to clay or paper mâché,” she reported, “they are not at all inhibited!”10 Listening to them chatter while they worked, she was transported back to her time at art school, to the joy that resounded in the “sound of the hammer and chisel in the free, open air.”11

“Their world was different from ours. We must start there.”12 So wrote Nathan Huggins about the Harlem Renaissance, to free himself and his readers from decades’ worth of knowledge of what that era and its personalities meant. Let us start there: is it possible to tell the story of Elijah Zwane’s “wonder” or to exult in the “free, open air” of such a place as twentieth-century South Africa? Between the 1950s and the 1980s, hundreds of black South Africans journeyed across their benighted land to a hillside school to paint, to carve, to model, to think. The evidence they left behind suggests that, for the most part, they enjoyed the experience. They held fast to it, treasuring the school, their talent, their vision, their changed selves, and the community they made there amid society’s storms.

We know a good deal about those storms. As a way of life, the “apartheid” for which these teachers worked is still little understood. As a concept, it is a term immediately grasped and then shelved with colonialism, racism, segregation, and the Holocaust—the litany of a century’s wrongs.13 Generations of activists, artists, scholars, and others have condemned apartheid’s violence and urged resistance. Yet the term apartheid itself continues to do tremendous violence to those who lived under that system: when we invoke the word—and especially when we append the categories black and South African to it—it becomes too easy to sit back, satisfied that we know the whole story.14

But even those who lived it and fought righteous struggles against the apartheid system can claim only an imperfect knowledge of what it meant to live in that time and place.15 Broad sociological claims produce similarly partial truths—about poverty, about oppression, about inferior education and corrupt and unresponsive bureaucracies. All are true—and all obscure other truths, about the decisions with which people were presented, about the opportunities they seized, and about their exertions for better and more meaningful lives. Life is multiple and contradictory, the political philosopher Richard Iton writes, and when seeking to grasp its various incarnations, “we cannot overlook those spaces that generate difficult data.”16 The Ndaleni art school was such a difficult place.

At a basic level of political and historical identification, the art teachers who passed through Ndaleni were cogs in the machinery of white supremacy. They taught a syllabus written by C. T. Loram’s children—bureaucrats charged with the maintenance of racial separation—and even when teachers could not teach that syllabus to the letter, their quest for materials reveals that they aspired to do so.17 They were also people open to the possibility of beauty, imbued with a confidence that if they could imagine something, they could materialize it; if they needed to say something, they could say it.18 They were thinking people in a time and place that did not necessarily reward their sorts of thoughts. They were relics of a bygone ideology, justly relegated to history’s scrap heap. Ndaleni generates difficult data precisely because it opens a window into the closed room of the past—through its archive, we can see the faces looking out at us, blind to the world of knowledge and hindsight that we inhabit. Twentieth-century South Africa was only one among many such rooms. Indeed, we live in another room today, a room whose boundaries we perceive dimly, if at all. What did it mean to dwell in that realm of perception?19 What comes of our “attempt to see through the looking glass of epistemological history”?20 The Art of Life in South Africa is the story of a community, a school, and the idea that people everywhere are creative beings, capable of making manifest their unique visions of the world.

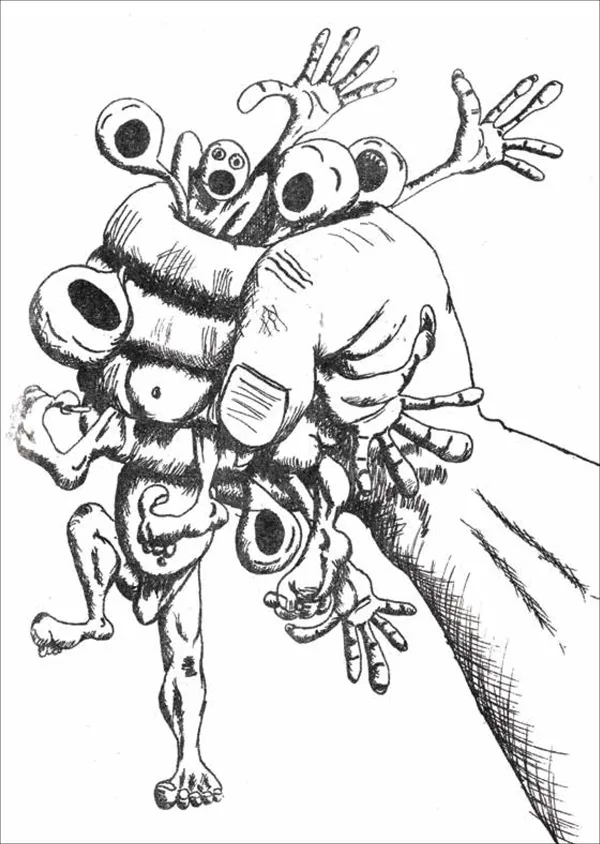

Figure 1.3 The Hand of Destruction, by Fish Molepo, ARTTRA, no. 38, October 1979, 22

TWENTIETH-CENTURY SOUTH AFRICA

Imagine a kiln. By the early 1960s, it was evident that the art school’s infrastructure was not up to its task. The syllabus called for students to be trained in clay, which was one of the few raw materials abundant in African schools because in many places—although not everywhere—it could be freely gathered from streambeds and other watercourses. In other words, the material was free only in the sense that it was paid for with students’ labor, not cash. The production of clay at Ndaleni art school was a bone-wearying process, involving trips to nearby streams to dig raw clay; hauling buckets up and down steep hills; and spending hours grinding, sieving, and curing raw clay for use in their art classes. All of this was arduous enough without the additional task of gathering wood to fire the students’ creations.

The students had no potter’s wheel, and they had no modern kiln.21 The first iteration of the Ndaleni art school newsletter begged supporters for £150 to buy an electric kiln to ease that last, excessive labor. Funds were not forthcoming, however, and it was not until the early 1970s that the Department of Bantu Education relented and delivered a brand-new, state-of-the-art, electric kiln to Ndaleni’s hillside campus.22 There it sat, untouched and unused, for a decade, until the school closed.

Figure 1.4 Stoking the kiln at Ndaleni, 1975, Ndaleni Scrapbook 4, with the permission of the CC

Ndaleni had electricity; the art school’s instructors might have plugged the thing in and made their students’ lives easier. Yet they understood too well the realities that would be faced by art teachers in the country beyond the campus. Bantu Education schools did not have electric kilns—many did not have electricity at all. It was better to continue to dig a hole in the ground, scrounge for bricks, and gather wood than to humor the department’s illusory modernity.23 The story of this cold electric kiln captures the reality of twentieth-century South Africa differently than do most history books. Both scholarship and popular memory typically capture the vastness of that time by focusing on a handful of well-told stories: the interwoven rise of the industrial state and political segregation, the maintenance of white supremacy and apartheid, and the “people’s” struggle for some sort of new po...