![]()

1

“Our Agricultural Brotherhood”

Origins, Purposes, and Structure

We propose meeting together, talking together, working together, buying together, selling together, and in general acting together for our mutual protection and advancement. . . . Sectionalism is, and of right should be dead and buried with the past. . . . In our agricultural brotherhood . . . we shall recognize no North, no South, no East, no West.

—Declaration of Purposes of the Patrons of Husbandry

Months before President Andrew Johnson formally declared an end to the US Civil War on 20 August 1866, he sent Bureau of Agriculture clerk Oliver Kelley to inspect the ravaged rural South. Six days after his fortieth birthday, Kelley departed Washington on 13 January 1866 and traveled across the South until 21 April, recording the effect of the war on southern agriculture.1 Although the South bore the brunt of the war’s devastation, farmers across the nation were suffering, especially when compared to the business titans emerging in the postbellum period.

A year and a half after Kelley’s southern journey, the Patrons of Husbandry were born. The first official meeting of what became the Grange took place on 15 November 1867 in Washington, DC, and officers were elected on 4 December 1867. By no means the first nor the only American agricultural organization, the Grange nevertheless stands out for its longevity.2 Improving the economic lot of farmers was its original focus, but the Grange has sustained itself primarily by its appeal as a fraternal and social association that engages in community service and political advocacy for farmers.

Setting the Stage for Farmer Discontent: Aftermath of the War

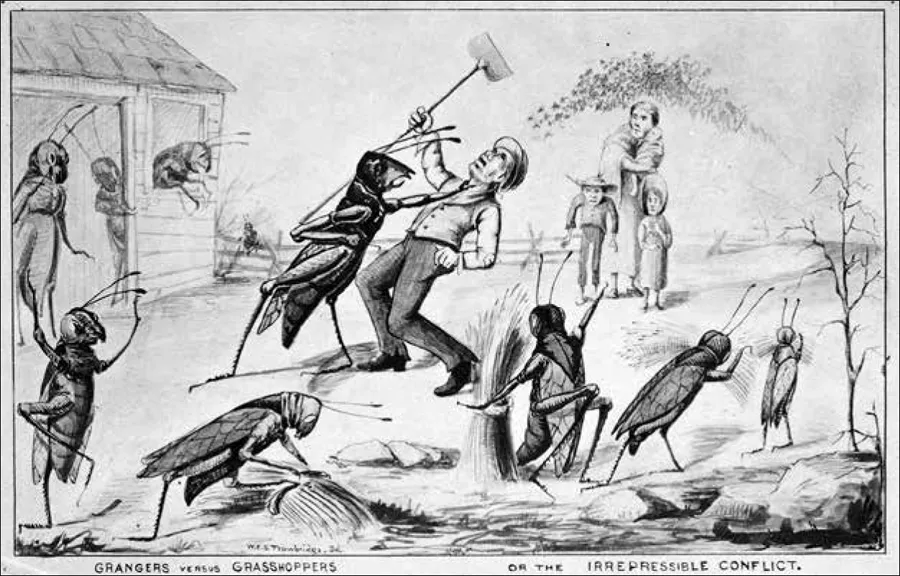

Military deaths during the Civil War accounted for more than 2 percent of the US population, with most of the dead being able-bodied men in their prime. An estimated one out of ten men of military age never returned home; nearly a quarter of Southern men ages twenty to twenty-four in 1860 lost their lives in the war. The demobilization of both armies sent hundreds of thousands of survivors back to their farms, but many of them returned to neglect and disarray. The men themselves did not always come back whole: for instance, 20 percent of Mississippi’s entire state budget in 1866 went for artificial limbs. Although the Homestead Act of 1862 had opened up cheap land to aspiring farmers, improved capital-intensive farm technology made it difficult for small farmers to achieve economic success. Tumultuous weather and periodic pest infestations (fig. 1.1)—described so vividly in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House books—added to the misery.3

The official cessation of conflict also meant a downturn in demand for rations, animal feed, wool, horses, and mules. Emancipation and Reconstruction generated major changes in agricultural supply as well. Former slaves met with resistance, political suppression, and violence as they sought to distance themselves from the plantation and to grow their own crops and food. The war was over, but the struggle to move from a slave to a free society had only just begun. Under the leadership of General O. O. Howard, the Freedmen’s Bureau made heroic efforts to smooth the transition, but lack of funds hampered the bureau, which was disbanded under President Ulysses S. Grant.

As a further irritant to farmers and other citizens, corruption plagued the postwar federal government. Perhaps the best-known episode was the Crédit Mobilier scandal, which consisted of financial hijinks by the directors of the Union Pacific Railroad abetted by certain members of Congress. The public learned the details of Crédit Mobilier in 1872, during Grant’s second run for office, but the shady behavior by government officials actually occurred during Andrew Johnson’s administration.4

Figure 1.1. Grangers versus Grasshoppers, 1880. Source: Minnesota Historical Society

Financial turmoil and monetary policy took its toll on postbellum agriculture as well. Many farmers experienced setbacks during the massive financial panic of 1873. What is more, the nation’s return to the gold standard after its experiment with greenbacks during the war meant precipitous price declines and financial uncertainty, which affected numerous farmers adversely.5

Even as farmers suffered, they observed others amassing enormous amounts of wealth. Extensive inequality existed in the United States throughout the nineteenth century, but it increased markedly between 1870 and the early twentieth century.6 Some of the richest men in American history built their fortunes starting during this time, including John D. Rockefeller, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and Andrew Carnegie. Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner satirized the greed of this period—and bestowed its name—in 1873 in their coauthored book, The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today.

In short, the time was ripe for farmers to find an outlet to express their discontent. The Grange provided it.

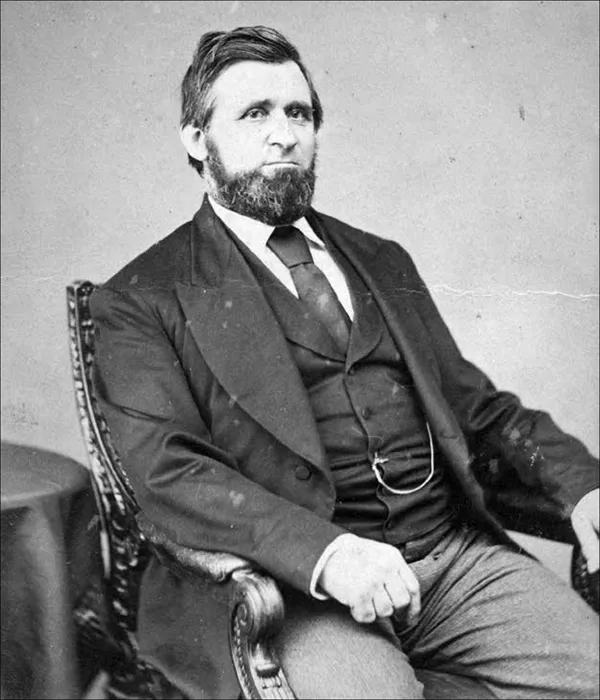

Figure 1.2. Oliver Kelley, 1875. Source: Minnesota Historical Society

Oliver Kelley and the Founding of the Grange

Kelley’s Early Years

Oliver Kelley (fig. 1.2) is generally acknowledged as the principal founder of the Grange, with his talent appearing to lie more in organizing than in actual farming. He grew up in Boston but moved to St. Paul in 1849, where he joined Minnesota’s first Masonic Lodge. Kelley’s connection with the Masons proved critical in helping him shape the Grange.7

Town life did not satisfy Kelley. After reading a number of books on agriculture, he bought land in Itasca—at the headwaters of the Mississippi River—in hopes that the territorial capital would move there and Kelley could benefit from a ready market for his crops. Unfortunately for him, a split vote in the legislature kept the capital in St. Paul. Kelley then established the first Minnesota agricultural society in 1852. His personal farm operation collapsed shortly thereafter, in part because Kelley tied up his cash in a real estate venture called “Northwood” that went bust in the Panic of 1857. Portentously, volatility in railroad stock prices contributed to this financial crisis.8

After drought destroyed much of the rest of his holdings, Kelley moved to Washington in 1864 to serve as a correspondent for the St. Paul Pioneer Press as well as a clerk in the Department of Agriculture. There, he struck up friendships with men who later joined him to organize the Grange. These included William Saunders, who headed the division of gardens in the Bureau of Agriculture and designed the military cemetery at Gettysburg; William Ireland, a clerk in the Post Office and a fellow Mason; and John Trimble, a Treasury Department clerk and an Episcopalian clergyman. In December 1867, Kelley and his colleagues formally elected the first officers of the Grange in Washington, DC.9

Organizational Growth, Methods, and Structure: The Heady Beginning

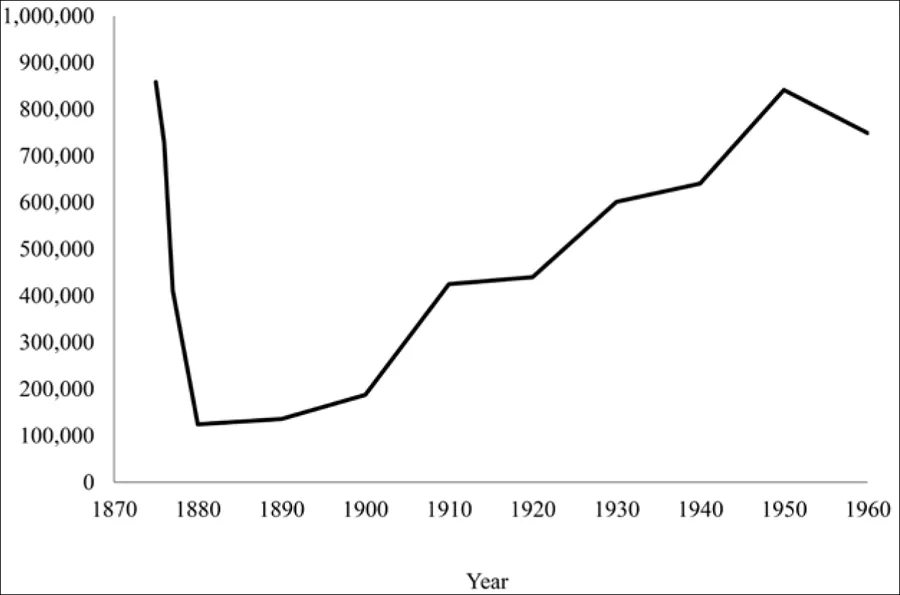

Membership in the Grange was never larger than shortly after its birth in late 1867, although it came close to its original size again in about 1950 (fig 1.3). Grange membership swelled considerably before the financial panic of 1873 began.10 But the panic made the Grange even more relevant: transportation-cost worries and financial irregularities (particularly among railroad enterprises) that surfaced as the panic spread encouraged the new farmer association to focus on collaborative enterprises and rate regulation. A number of financial institutions—including Jay Cooke & Company, which had helped the federal government with innovative financing techniques during the Civil War—failed during the panic due to railroad loans gone bad. This added steam to the budding farmer movement.

The founders of the Grange set up a temporary national organization, but they intended its structure to grow from the ground up, with the fundamental building block being a subordinate Grange made up of at least thirteen initial members.11 Each subordinate was to have at its helm a “Worthy Master,” along with other officers. Kelley and his companions envisioned an eventual web of subordinates spun across the nation, woven together to form larger county- and statewide Granges.

Figure 1.3. Grange Membership, 1875–1960. Source: Tontz (1964, table 1)

The beginning was rocky, as Kelley’s initial attempts to inaugurate subordinates on his own mostly failed. Kelley organized the first permanent subordinate in Fredonia, NY, in April 1868 but was unsuccessful in establishing others as he traveled from Washington back to his Minnesota home. By 1871, four years after the inception of the National Grange, only 180 subordinate Granges existed across the country, with three-quarters seated in Iowa and Minnesota. These were arranged concentrically by date of creation around Oliver Kelley’s farm (fig. 1.4). Only three State Granges had formed by 1871, with Minnesota leading the way in 1869, followed soon by Iowa and Wisconsin.12

Kelley then hit upon a surefire formula: send a paid recruiter to obtain an introduction to a leading farmer, win over the farmer by stressing the practical benefits of the Grange, and enlist the farmer’s help in signing up his neighbors. Colonel D. A. Robertson, a fruit grower, journalist, legislator, and sheriff, spearheaded much of the early recruitment effort. By choosing respected men in the community to lead the charge, particularly in the South, Kelley’s army of recruiters soon met with considerable success. A. J. Rose, a rancher, farmer, and education reformer, was a prime example in Texas. Rose reassured wary farmers that the organization was fundamentally conservative in nature and pointed to its refusal to ally itself with the Knights of Labor (one of the largest and most influential labor unions of the 1870s and ’80s) as proof.13

Figure 1.4. Oliver Kelley Farm, 2013. Source: Photograph by Austin Wahl

In Minnesota, many people organized a single subordinate Grange, but a few organized huge numbers of them. Among all those involved, 65 individuals organized only one subordinate each and 49 organized between two and four subo...