![]()

1

Drought and New Mobilities in the Omani Interior

“He who eats her halwa must [also]

patiently endure her misfortune”

“If fortune does not obey you, follow it so

that you may become its companion.”

—Nineteenth-Century Omani Proverbs

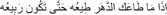

IN THE 1840S, Nizwa, one of the largest and most important towns in the Omani interior, and its environs were struck by a severe drought. This drought lasted for more than five years, disrupted the normal patterns of life, and resulted in mass emigration. The festival (’eid al-adha) marking the culmination of the Hajj in 1845 reflected the impact of this environmental crisis. Because of the drought, Nizwans were unable to celebrate in their normal manner. The eighty-foot-tall fort at the center of Nizwa commanded a view of what had been, in more prosperous times, extensive date groves. As a meeting place of four streams, Nizwa was generally well watered, and, consequently, its citizens were well off. Writing forty years after the drought, S. B. Miles noted that Nizwa surpassed “all the towns of Oman in its supply of water, natural wealth, and the industry of its inhabitants.”1 Before the drought in the 1840s, the area’s agriculture supported a population whose size was second only to Muscat, and its industry included “famous and extensive” textile and embroidery works. Nizwa grew cotton and indigo, and women spun and men worked looms to produce blue cotton goods.2 Nizwa was also a religious capital, known as bayḍat al-Islam, the core—literally, “egg”—of Islam, for its historical role in maintaining the Ibadi Imamate.3 The people of Nizwa prayed and studied in three hundred mosques.

During the December 1845 festival (’eid), however, something was amiss. A procession of drummers and horn players led cheering men to the central square for mock fighting with swords, spears, and matchlocks. Women watched the festivities from the rooftops. But the normal celebrations lacked something important. The ’eid al-Adha celebrations of the Hejira year 1261 went on for a typical three days, but the circumstances—namely, the five years of drought—meant that anxiety plagued people from every social class. With the central market closed and commerce suspended, adults worried about rain. Would this be the year? More immediately, those who anticipated the delectable sweetmeats for which Nizwa was famous felt the sting of the drought. There was no halwa. None of the sweet delicacies were procurable. And it was not simply a question of obtaining the ingredients. Many families had left Nizwa because of the drought and mysteriously, the departed included all of the confectioners.4 The out-migration of confectioners, who were people of humble status, offers new clues on the mobility and circulation of people within Arabia and beyond.

FIGURE 1.1. Nizwa fort, silent witness to the 1840s drought. Percy Cox took this photograph in 1901. “Some Excursions in Oman,” Geographical Journal 66, no. 3 (September 1925).

The long drought and the loss of viable agricultural lands around Nizwa caused people to flee. While some moved to places in the interior or to the coastal towns of Oman, others went farther afield. One Nizwan became an important property broker in Zanzibar. Juma bin Salim al-Bakri, whose story was introduced earlier, amassed huge ivory holdings at his headquarters in the eastern Congo. And, fifteen years after the halwa-free Hajj festivities, a confectioner who had traveled through Muscat to East Africa became a trade agent and “big man” in the most important trading depot in central Africa. Thus, in that drought-stricken festival in 1845, while the men of Nizwa sipped coffee in the evening and listened to a poet sing his verses, they were likely worrying about the ruin of the whole province. They probably could not have imagined how far the drought would compel their neighbors and countrymen to travel.

* * *

This chapter examines eastern Arabia in the early nineteenth century to explain the environmental, social, and political conditions that prompted Arab migration to East Africa. The Omani ruler Seyyid Said bin Sultan al-Busaidi’s reasons for shifting his capital to Zanzibar in 1832 were financial and geostrategic, but what motivated others?5 Despite the important connections, many histories focused on East Africa have taken Arab migration for granted and overlooked push factors.6 Surprisingly, many of the Arab migrants who traveled to Africa in the nineteenth century were people of modest means from interior towns, not wealthy traders from port cities. Rather than neglect the Omani interior, this chapter focuses on the patterns of circulation that connected Arabian oasis towns like Nizwa to far-off Zanzibar and new settlements in eastern and central Africa.

This story necessarily begins with the underlying geographical and environmental factors that shaped human settlements in interior Oman and ends with threats that periodically upset these settlements. The management of water shaped Omani settlement patterns, and this chapter takes up the technological adaptations and religious traditions that addressed environmental limitations. Scholarly approaches that have presupposed a false dichotomy between static interior societies and enterprising coastal peoples have misread Omani history and misunderstood the processes that linked the interior regions of Arabia and Africa. Seyyid Said bin Sultan’s activity in the Indian Ocean, and his outposts in Africa in particular, renewed circuits of travel and created new opportunities. Thus, when Arabs in Oman were faced with progressively more difficult choices about how to handle constricting droughts or devastating floods, a new temporizing strategy—decamping to Africa—was open to them.

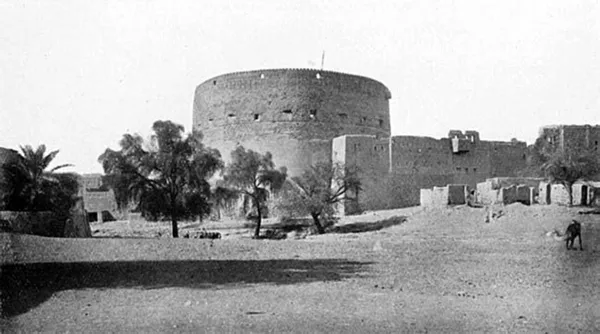

MAP 1.1. Oman and its surrounding regions

GEOGRAPHY

Oman’s peculiar geography has made it both relatively isolated from the Arabian Peninsula and well connected to maritime networks. The region’s geography has created unusual patterns of rainfall and runoff, and humans have built irrigated settlements that are well adapted to these arid, rugged conditions. Oman’s seemingly contradictory forces of isolation and integration have also sustained Ibadism, a sect of Islam that is neither Sunni nor Shi’a, though regional dynamics have also undermined Ibadism’s ideal form of governance, the imamate.7 These forces have also tempted scholars to mistake the country for a static interior cutoff from the littoral, a view derived from the country’s twentieth-century history, when it was known as the Sultanate of Muscat and Oman, than from the preceding century, which is our focus.

Geography is inherently visual and most easily understood through maps or metaphors. It is useful to imagine the Arabian Peninsula as a boot. Viewed from the side, the boot has a heel, Yemen, which nearly rests on the Horn of Africa. The boot’s spiked toe pokes into the Straits of Hormuz, the passage into the Persian Gulf. The countries of the eastern Mediterranean (Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan) serve as the boot’s pull straps at the top, and Saudi Arabia is the boot’s thick shaft. Oman is the boot’s toe box. The top of the toe box curves out into the Persian Gulf’s entrance, and the toe box meets the outer sole at Ras al-Hadd, the eastern-most point of the peninsula, which juts out into the Arabian Sea of the Indian Ocean.

As it turns out, this particular boot is steel-toed: mountains line the inside of the toe box and seem to cut off (or protect) the interior from the outside world.8 These mountains, called the Hajar range, run for more than three hundred miles (500 km), are seventy-five miles (110 km) at their widest, and reach to nearly ten thousand feet (3,000 m) at their highest point, Jebel Akhdar (green mountain). The range only breaks at a few points, where drainage has created passes through the mountains. On the sea side of the mountains, a coastal plain known as the Batinah (al-Bāṭinah) fills the gentle arc at a width of twenty miles. The mountains draw close to the shore again, and the Batinah ends at an important pass—the Sumayl Gap—through the mountains, right before the twin ports of Muttrah and Muscat. The steep mountains plunging to the sea create the natural harbors of Muttrah and Muscat, and the Sumayl Gap is the broadest break in the mountains. Historically, Sumayl was a vital link between the coast and the interior for the movement of people and goods; control of the pass had military implications for the ruler and those who wished to challenge him.

The Omani interior lies between the landward side of the Hajar range and the desert forelands of central Arabia. This region was historically known as Oman, so the modern nation-state derives its name from its interior rather than its more famous coasts. Thus, referring to the “Omani interior” is something of neologism. In the interior, the mountains give way to a bajada zone of alluvial fans that reach out to a vast waterless plain before running into the desert sands.9 Primary settlements exist in the mountains, on the piedmont, and out in the plain. Movement along the outwash fans is much easier than crossing the mountains or the desert, facilitating exchange between interior settlements. In this sense, if we imagine the desert as the sea, the Omani interior shares characteristics with littoral societies: greater similarities in location, occupation, and culture to those on the littoral than to those in the hinterland.10 The interior settlements fall into two general regions, al-Dakhiliya and al-Sharqiya. Al-Dakhiliya (literally, “the interior”) is the central region, snugged south and west of the Jebel Akdhar massif. To the east, al-Sharqiya (literally, “the east”) is hemmed in by the Hajar Mountains to the north and east. The region gives way in the south to the Wahiba Sands. The Sumayl Gap connects Dakhilya and Sharqiya to the ports of Muscat and Muttrah, and Sharqiya also has a connection to the port of Sur to the southeast.

IBADISM

Another defining aspect of the Omani interior has been its religious character. Oman has been the home of Ibadi Islam for 1,200 years. Ibadism (Ibaḍiyya) is a sect that separated from mainstream Islam in 37 AH/657 CE, before the better-known divisions of Sunni and Shia took place. Ibadis refer to themselves as “the people of straightness” (ahl al-istiqāma), and they believe they are the practitioners of “the oldest and most authentic form of Islam.”11 Ibadi theology centers on a longing for a righteous imam who scholars and pious leaders select to facilitate the believers’ ability to live in an ideal society defined by piety and justice.12 Striving to achieve this righteous imamate has been a touchstone of Omani history, and Wilkinson has proposed an “Imamate Cycle” as a means to explain the Omani past. In this view, new imamates have strong ideological power, but when the ideological basis of the Ibadi imamate weakens, the struggle for power and wealth increases, and this struggle leads to a revival of tribal factionalism.13 Elected imams ruled Oman from the interior towns, generally Nizwa or al-Rustaq.

While the first Busaidi ruler of Oman, Ahmad bin Said, was proclaimed an Imam in 1749, his descendants who have ruled the country have not been elected as imams since the late eighteenth century. In 1785, Imam Ahmad’s grandson, Hamed bin Said bin Ahmad (r. 1784–1792), shifted his seat of power from al-Rustaq, where his father had ruled, to Muscat in order to take advantage of the Indian Ocean trade.14 While trade connections and migration to Africa led some Ibadis to adopt Sunnism, Ibadism thrived in the Omani interior and remained a potent political discourse for challenging the Busaidi sultanate over the last two hundred years. Ibadism has only recently attracted broader scholarly attention, and the Omani interior’s distinctive relationship with this religion contributed to broader misunderstandings of the region.

MISREADING THE INTERIOR

While the coastal Indian Ocean port cities of eastern Arabia have long been cosmopolitan centers, scholars have considered the interior of Oman to be isolated, static, and conservative. Yet it was interior Arabs, from Oman proper, who took to the Indian Ocean in great numbers in the nineteenth century. The imagined dichotomy between an outward-looking coastal people and an inhospitable interior inhabited by backward, fearsome people echoes the view that both contemporaries and scholars held about East Africa’s coast and interior. In this false geographical determinism, the mountains and deserts of Arabia played the same role as the sup...