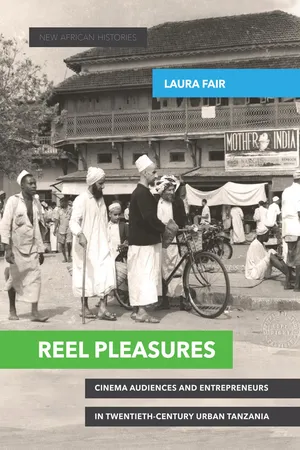

![]()

Chapter 1

BUILDING BUSINESS AND BUILDING COMMUNITY

The Exhibition and Distribution Industries in Tanzania, 1900s–50s

THE ENTREPRENEURS who built the exhibition and distribution industries in East Africa were businessmen, and like their counterparts the world over, their aim was to turn a profit. But business cultures everywhere are also historically situated and socially constructed. In early twentieth-century East Africa, the capitalist profit imperative was tempered by local cultural norms and religiously sanctioned obligations that made sharing wealth and investing in community corollaries of individual accumulation. Wealth was revered—but all the more so when it was shared. “Big men,” esteemed women, and respected families earned their social status by financing cultural troupes, religious festivals, or large public parties that brought the community together. Privately investing in public infrastructure (such as wells, waterworks, schools, mosques, and hospitals) was another common means of redistribution. Immigrants and the children of immigrants abided by these customary standards as much as the native born did, for this was an effective way to signal their commitment to belonging and to foster social bonds in their new home.1

For the men who built the exhibition industry in Zanzibar and Tanganyika in the early 1900s, one critical factor in evaluating business returns was the degree to which a capital investment helped build a good city and put one’s town on the map. As of the 1930s, only nine towns were able to boast of regular film screenings (see map I.1). These towns were in their infancy at the time—a small fraction of their size and population today—and were built largely of impermanent materials such as mud and stick and thatch. Investing in a building like the Royal in Zanzibar, the Regal in Tanga, or the Tivoli in Mwanza signified a man’s belief in the solidity and prosperity of the future, as well as his commitment to the beautification of a town’s built environment. Cinemas were among the largest and most architecturally innovative buildings in any town, and bringing the latest global media to the community added a touch of cosmopolitan spark to local life. Building a public space where hundreds came together demonstrated one’s willingness to invest in urban civic and artistic culture.

The men who built the industry incorporated elements of preexisting leisure and business customs into cinema’s commercial culture. Like turning a profit, the desire to outdo a rival was a basic business motivation. But in East Africa, the rivalry between theaters was infused with elements from local song, dance, and football competitions. Leisure group competitions were at their most intense when a club had a known competitive rival, and the same was true for cinematic exhibition. Through innovative architectural styles, technological acumen, and the display of the best and most recent films, rival exhibitors continuously strove to win the contest for loyal fans, and moviegoers benefited as a result. This may sound like business competition anywhere, but in the small, face-to-face environment of East African towns, it took on a distinct quality. Business relationships between distributors and exhibitors also incorporated elements of the patron-client relations that infused nineteenth-century business and leisure networks. Building social capital and enhancing a reputation as a trustworthy, dependable individual were deemed far more critical to business success than amassing quick profits. And in the industry in Tanzania, unlike in some other capitalist cultures, the goal was never to eliminate one’s rival but rather to outclass him.

BUILDING HOMES AND INVESTING IN PLACE

The earliest displays of moving pictures were introduced to East Africa by merchants, traders, and sailors traveling the oceans aboard British and Indian vessels. By 1904, if not before, exhibitions of moving pictures had become an exciting and regular feature of urban nightlife in Zanzibar Town.2 Local audiences could never be sure when a man carrying a hand-cranked projector and a few reels of film along with his other goods would arrive, but when he did, word quickly spread.3 Little was required to muster a crowd other than finding a place to hang up a sheet as a makeshift screen: by nightfall, a sizable audience was virtually guaranteed. Given the public’s enthusiasm, what began as an itinerant sideshow quickly grew into a permanent venue with regularly scheduled displays.

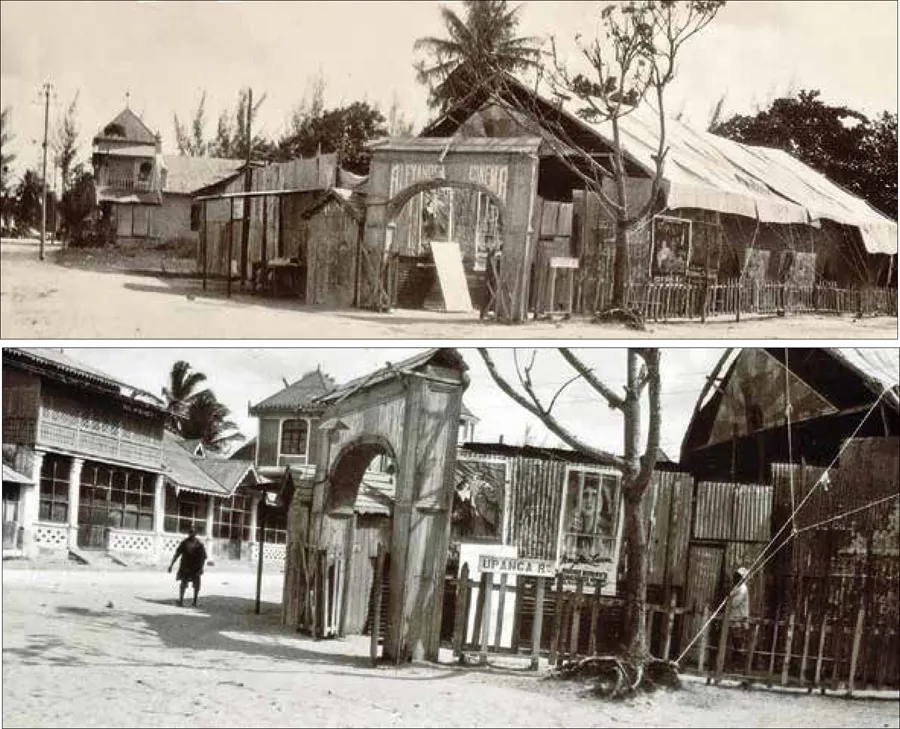

Hassanali Adamjee Jariwalla began as an itinerant showman when he was barely twenty and went on to pioneer the formal industry in East Africa. Jariwalla was actually employed by a firm in Bombay as a cloth merchant and traveled by dhow on the monsoon winds taking goods from India to Madagascar and Zanzibar each year. On one trip, according to his grandson, someone in Bombay offered him films and a portable projector to carry together with his other wares,4 and just for fun, he took them along. Soon, he was providing itinerant shows when the dhow he was traveling on reached port, and the enthusiastic welcome that greeted his arrival each season encouraged him to start putting on regular shows. In 1914, he settled permanently in Zanzibar, choosing to make it his new home. That same year, he opened the region’s first semipermanent exhibition hall inside a khaki tent adjacent to the central market, in the neighborhood of Mkunazini. He named the theater the Alexandra, and Zanzibar’s Official Gazette proudly advertised that the latest releases from India, Europe, and the United States could be seen there each night. Within two years, Jariwalla was operating two such venues in Zanzibar, as well as a third in the Upanga neighborhood of Dar es Salaam.5

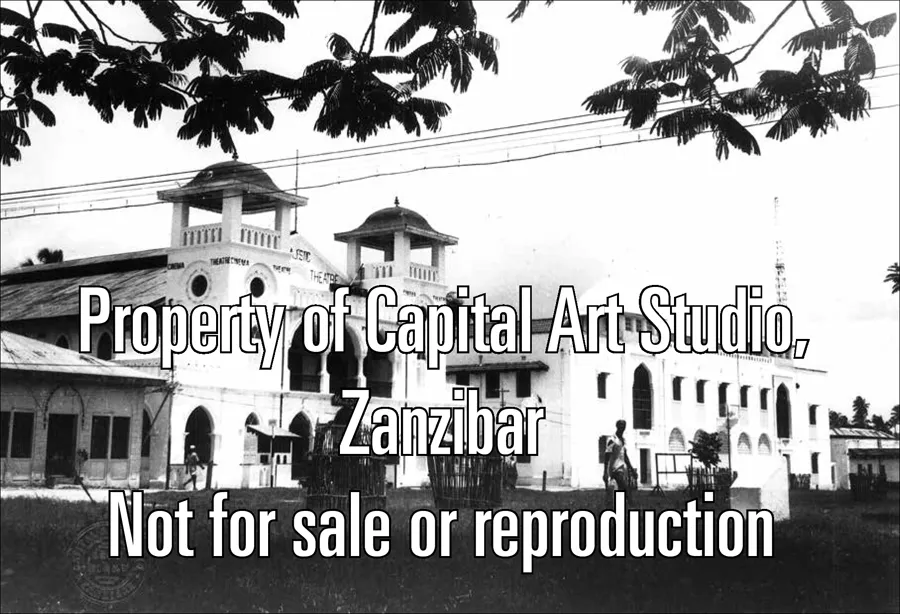

Business was brisk, inspiring him to draw up plans to transform his exhibition venues from makeshift tents into rock-solid picture palaces. He took what certainly must have seemed a crazy risk, investing his hard-earned savings from the cloth trade in erecting East Africa’s first luxurious cinema—the Royal Theater, which opened in 1921 on the site now occupied by the Majestic Cinema. The Royal was one of the grandest public buildings in Zanzibar and certainly the only piece of architecture of its stature devoted to entertainment.6 Designed by the British resident, J. H. Sinclair, who was trained as an architect, the theater was built in the Saracenic style popularized across the British Empire by those who sought to incorporate so-called Muslim domes and Indian arches into imperial design.7 Sinclair may have dictated the facade, but Jariwalla insisted on the content. The Royal was a large and modern theater on a par with the best operating anywhere in the world at the time. With room for nine hundred seated patrons, as well as box seats and a balcony, the latest projection equipment, and new releases from three continents, the Royal was as impressive as its name implied.8

Figures 1.1 a, b Alexandra Cinema, Dar es Salaam, c. 1916. Images courtesy of the Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies Winterton Collection, Northwestern University

Why would a young South Asian merchant risk his savings by sinking everything into an unproven industry and an outlandishly expensive building in Zanzibar? To be sure, the crowds drawn to the moving pictures in the town seemed insatiable, and Jariwalla was clearly of an entrepreneurial spirit. But if it was possible to make people happy showing them silent films inside a tent, why invest something on the order of a million dollars to build a picture palace?9 This was Africa, after all. Wouldn’t a makeshift tent suffice? And when the average weekly attendance was five hundred patrons who paid less than ten cents for each ticket, how many shows over how many decades would it take to pay off the cost of construction, let alone turn a profit? Furthermore, how sure could anyone be in the 1910s that cinemagoing would be an enduring pastime—especially in East Africa, which was in the early, brutal years of imperial conquest? To comprehend the rationale behind building a cinema in colonial Tanzania, we need to see that investments of this type were about much more than monetary profit: they earned proprietors, townspeople, and even colonial officials valuable social and cultural capital.

Figure 1.2 Royal Cinema, Zanzibar, opened 1921 (renamed the Majestic in 1938). Photo by Ranchhod T. Oza, courtesy of Capital Art Studio, Zanzibar

All the men who built cinemas in Tanzania were either immigrants or the children of immigrants, but after settling in Zanzibar or Tanganyika, they invested heavily in developing not just business and commercial networks but also the physical, social, and cultural infrastructure of their towns. Sinking their capital literally into the ground spoke louder than any words could about their commitment to making East Africa home. The architectural history of the region is largely a lacuna, but Robert Gregory estimates that upwards of 90 percent of the cityscape in East African colonial towns—from private homes to markets, courthouses, and schools—bore the mark of immigrant Asian contractors, architects, craftspeople, financiers, and laborers.10 From private homes and shops to public buildings of many types, South Asians played a major role in giving East African towns concrete form. Privately owned buildings offered opportunities to display artistic style, architectural competence, and financial power.11 And cinemas, as monuments to the idea of a collective public sphere, enabled businessmen to demonstrate their commitment to building a beautiful town and a social community as well.

The religious traditions and personal experiences of many South Asian immigrants helped generalize expectations that financial success came with communal obligations. Many early immigrants were from regions prone to drought, famine, and debt. Most had fled because they had few other options. A common trope in the stories of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century immigration is the young man, perhaps barely in his teens, who arrives in East Africa poor and alone. He is saved from abuse and the vagaries of life only by the generous intervention of some kind soul who takes him in; provides food and shelter; gives him a job; and helps him mature into a solid, successful, and respected man.12 In fact, a number of poor immigrant boys became some of the wealthiest and most powerful men in East Africa. And according to individual and communal narratives, they never lost sight of where they came from. Personal experience both inspired and obligated them to help others.

In neither India nor East Africa did the colonial state invest substantially in health, education, or social welfare. Consequently, such obligations fell largely on local communities. South Asians built many formal and informal institutions for fund-raising and communal development; the annual tithe of 10 percent of one’s income collected by Shia Ismailis and Bohora Ithnasheris for communal investment was but one expression of the strong commitment to social improvement. These acts of philanthropy were, of course, just as fraught with struggles over class, gender, and religious norms and decorum as benevolent donations by the Fords, Rockefellers, or Gateses, but they were still critically important for feeding the hungry, healing the sick, and housing the poor. They also reinforced the conviction that financial success came with communal obligations. Many of the first public hospitals, clinics, and maternity wards in East Africa were built and endowed by successful South Asians, as were some of the best public libraries, the first universities and preschools, sports stadiums, social halls, cultural centers, and public parks. In many instances, these institutions were the first of their kind serving all, regardless of race, religion, or class.13 By making charitable gifts, endowing public institutions, and supporting critical social welfare institutions, individuals and families displayed their wealth, demonstrated their generosity, and enhanced their own social standing as patriarchs and communal elders. Through generous giving, they acquired blessings in the afterlife and social power in the here and now.

Cinemas were certainly not charities like orphanages or medical clinics, but they were nonetheless treasured gifts to the community: they healed souls, opened minds, and provided aesthetic and emotional nourishment for old and young alike. They were, to be sure, businesses first and foremost. But investing in a business enterprise that simultaneously provided a social good was a culturally and historically specific ideal of prudent spending. The men who built East Africa’s cinemas were typically of much more modest means than those who endowed the universities and hospitals, yet in giving what they could, they too sought to endow their communities with cultural facilities. Cinemas were also frequently given over to charity organizations for fund-raising events, further demonstrating the owners’ commitment to philanthropy. As early as 1920, for example, Jariwalla was dedicating the proceeds from various evening shows to charity, a tradition that was followed by proprietors up through the 1980s. Exhibitors were also known to dedicate proceeds to fledgling political parties or public institutions, including the police, schools, and sports teams. In addition, owners and managers frequently allowed local social groups to utilize their facilities rent-free for music, dance, and theatrical shows.14 Charitable donations enhanced the personal and institutional bonds between theaters and the people of the town.

PROJECTING MODERNITY, TECHNOLOGICAL SOPHISTICATION, AND COSMOPOLITAN CULTURAL STYLE

The social capital that came from having a cinema accrued to the community at large as well as to the proprietor. One recurring theme across the hundreds of interviews conducted for this project was that having a cinema of any kind, especially one as beautiful and impressive as the Royal, dramatically enhanced the cachet of a town and, by extension, the prestige of its people. Haji Gora Haji, a poet and film fan from Zanzibar who worked as a sailor on a jahazi (sail-powered cargo boat) in his younger days, described the status he and his crewmates enjoyed as Zanzibaris when they docked in “sleepy backwater towns” along the coast where few had ever witnessed the wonders of moving pictures. The two main islands comprising the Zanzibar archipelago, Unguja and Pemba, boasted six cinemas during much of Haji’s life, making it the equivalent of a regional cultural Mecca.15 Coming from a place with so many cinemas also gave young, economically poor but culturally rich Zanzibaris, Haji among them, artistic license to weave enraptured tales of evenings at the moving pictures for adoring crowds—tales that allegedly inspired others to stow away onboard boats headed to Zanzibar.16

Like picture palaces erected elsewhere in the world, the architecturally opulent theaters built in East Africa were intended to serve as spectacles and as sources of visual pleasure in and of themselves. At a time when the vast major...