![]()

Economists agree: The single biggest threat to future job growth in the United States is the surge of artificial intelligence. Gallup, January 2018

America is finally approaching full employment. But a chorus of experts claims that this happy situation will be short-lived. Their warning is not the usual one about unemployment rising again when the next recession hits. Instead, the proposition is more ominous: that technology is finally able to replace people in most jobs.

The idea that we face a future without work for a widening swath of the citizenry is animated by the astonishing power of algorithms, artificial intelligence (AI) and automation, especially in the form of robots. At last count, more than a dozen expert studies, each sparking a flurry of media attention, have offered essentially the same conclusion: that the amazing power of emerging technologies today really is different from anything we’ve seen before; that is, the coming advances in labor productivity will be so effective as to eliminate most labor.

It has become fashionable in Silicon Valley to believe that, in the near future, those with jobs will comprise a minority of “knowledge workers.” This school of thought proposes carving off some of the wealth surplus generated by our digital overlords to support a Universal Basic Income for the inessential and unemployable, who can then engage in whatever pastime their heart desires, except working for a wage.

It is true that something unprecedented is happening. America is in the early days of a structural revolution in technology, one that will culminate in an entirely new kind of infrastructure, one that democratizes AI in all its forms. This essay focuses on the factual and deductive problems with the associated end-of-jobs claim. In it, we explore what recent history and the data reveal about the nature of AI and robots, and how those technologies might impact work in the 21st century.

But before mapping out the technological shift now underway and its future implications, let’s look for context at previous revolutions in labor productivity.

One of humanity’s oldest pursuits is inventing machines that reduce the labor-hours needed to perform tasks. History offers hundreds of examples. Each invention seemed amazing in its era. To note a handful of examples, in modern times, we have seen the arrival of the automatic washing machine in the 1920s; the programmable logic controller (PLC), which enabled the first era of manufacturing automation in 1968; the word processor in 1976; and the first computer spreadsheet in 1979.

History demonstrates that, when it comes to major technological dislocations, most forecasts get both the “what” and the “when” wrong.

As with the “typing pools,” rows of accountants “ciphering,” rooms full of draftsmen with sharp pencils, or other common workplace sights from bygone eras, it is easy to predict which groups will lose jobs from gains in labor productivity. It is far harder, on the other hand, to predict the kinds of new jobs and how many will appear. It’s easy to see how an economy expanding due to accelerated productivity leads to added wealth, which, in turn, leads to more demand for existing products and services, all of which entail labor. But it is more challenging to predict the specifics of how new technologies invariably lead to unanticipated businesses producing new kinds of products and services, all employing people in entirely novel ways.

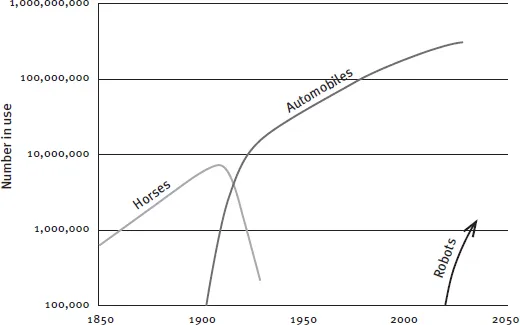

One of the most powerful advances in the history of labor productivity was the arrival in 1913 of a practical automobile. The very word “automobile” was coined to describe the automation of mobility, a long-time goal of humanity. The transition from grain-fed horses to petroleum-fueled automobiles took place with astonishing velocity precisely because the productivity benefits were so profound. (See Figure 1.) Along the way, as every schoolchild learns, the automobile totally upended the character and locus of every kind of employment associated with centuries of transportation services. Gone forever were all the jobs and millions of acres of land devoted to the feeding, care and use of horses.

The 1956 invention of the shipping container—an idea patented by U.S. trucking-company owner Malcolm McLean—also radically increased labor productivity. Containerization led to a 2,000% gain in shipping productivity in just five years and the end of centuries of rising employment for longshoremen (and, historically, they were all men). That gain in productivity rivaled that which took place in the previous century with the switch from sail to steam power: both radically lowered shipping costs, and both propelled world trade, prosperity and, derivatively, employment.

Figure 1. Grand Transitions in Labor Productivity, 1850–2050 (Projected)

Source: Adapted from Nakicenovic, Nebojsa

Containerization is also a clear example of how a new mode of business is made possible by building on a machine-based infrastructure invented and deployed by others: containerization could not have been effected prior to the availability of the precision powered cranes and gantries. That model matches exactly what Sears and Roebuck did in 1892, using the existing railroad infrastructure to launch their revolutionary retail empire, and what Amazon did a century later, using the existing Internet infrastructure to do the same.

One could wax lyrical about the pursuit of productivity. After all, the single most precious resource in the universe is the corporeal time we humans have. Maybe, someday, genetic engineers will find magic to change that. But it remains the case that every human being is born with a “bank” account with a maximum balance of about one million living hours. As with money, a million sounds like a lot—until you start consuming it.

Using technology to reduce or amplify human labor is more than metaphysical, though. Productivity is central to economic progress. As economic historian Joel Mokyr has pointed out, technological innovation gives society the closest thing there is to a “free lunch.” From the dawn of the industrial revolution, it has enabled the near-magical increase in the availability of everything, from food and fuel to every imaginable service. There is an enormous body of scholarship devoted to the study of how productivity increases both wealth and employment. Providing a coherent theory around that reality earned Robert Solow a 1987 Nobel Prize.

Epoch-changing shifts in technology do two inter-related things: they propel economies, and they introduce unintended disruptions across society. None of history’s technological disruptions were predicted by economists or policymakers. But once a disruption is underway, pundits pile on fast with predictions about implications and impacts—predictions that are almost always wrong, both in character and in outcomes.

Now, again, we are at the beginning of a new technological epoch, this one characterized by the infusion of automation into everything. This transformation comes at a propitious time.

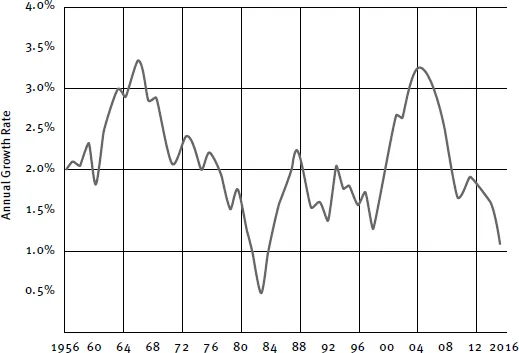

For a decade now, America has been in a productivity deficit. (See Figure 2.) By definition, this means that America is under-invested in productivity-driving technologies. Thus, while much has been written about the causes and management of the recent “great recession,” one cannot blame automation for the high unemployment rates during this period of anemic growth. Put another way, if automation is eliminating jobs, we would see a collateral increase in productivity, because businesses invest in automation only if it improves productivity; that’s the whole point.

Spending on new productivity-driving technology happens at the confluence of two forces. First, financial, tax and regulatory conditions must be favorable for accessing and deploying capital. Technology always entails capital spending. Second, the new technologies are purchased at scale only when they are sufficiently mature. Maturity isn’t just a cost metric. High costs can be justified if outcomes yield greater benefits. The key signal of maturity is when a technology becomes relatively easy to adopt within the organizational and human practicalities of any enterprise.

Figure 2. U.S. Productivity Growth, 1956–2016

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Back in the 1970s, economists were puzzled by a productivity collapse similar to our current one. No productivity gains were apparent from the then recent mainframe computer revolution, a time, incidentally, when IBM enjoyed a dominant market share matched today only by the likes of Amazon’s dominance in Cloud hardware. Few experts—arguably no one—in the 1970s foresaw what would emerge in the decades that followed.

The 1976 economic report to Congress by the Council of Economic Advisers (chaired by Alan Greenspan) did not contain the word “computer.” Missing the computer revolution in economic forecasts at that time was understandable, but no small error.

The systemic economic and societal impact of computing would not manifest itself until later, with the emergence of broadly distributed personal computing. Similarly, the associated employment of millions of people would not show up until the explosive growth of personal computing and the rise of firms like Intel and Microsoft.

Now, in the early part of the 21st century, it is clear from the trends seen in Figure 2 that the nation is at or near the bottom of a productivity cycle. Today’s state of automation and AI is no more broadly distributed than computing was in the mainframe era (1960–1980). The next incarnation of productivity-driving computing technology has yet to be democratized. When it is, we can expect a surge in productivity and economic growth for America.

There is one thing we know about economies: while robust growth can’t solve all of society’s problems, it can go a long way toward ameliorating many of them. But many economists and forecasters have been claiming that America is in a “new normal” in which GDP growth is going to hover around an anemic 2% a year for the foreseeable future.

As every economics student learns, rising productivity is precisely what creates economic growth. This is not debatable. Where there are debates, they center on what policies will best ensure productivity and whether, for example, bureaucrats can stimulate or direct the emergence of technologies that increase productivity. Only a small uptick in productivity is required to restore the U.S. economy to an average of 3% to 4% annual GDP growth.

At a 3.5% annual growth rate, by 2028 the U.S. economy would be $3.6 trillion bigger than one that staggered along at a 2% rate. The latter is the growth rate assumed by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) for calculating the deficit and other amounts. The CBO, by default, assumes that technology-driven productivity advances won’t emerge; this assumption requires myopia, a lot of hubris, or both. A nearly $4 trillion increase in the GDP would bring extra wealth equivalent to adding a California plus a Texas to the U.S. economy. It also would represent a cumulative addition to the economy about equal to the federal debt.

So we find ourselves at a curious place in history. If the automation-kills-jobs thesis is correct, then America’s future is one—the claim goes—in which robots and AI make us richer overall but with most work found in the “knowledge economy,” while jobs disappear everywhere else. Hence we see the resurrection of the idea of a Universal Basic Income (UBI), funded by taxing either robots or those companies deploying AI—that is, invisible virtual robots in the Cloud. The end-of-work adherents argue that a UBI is needed to support the “inevitable” rise of a permanent unemployed class. Is there any precedent in history for such an outcome?

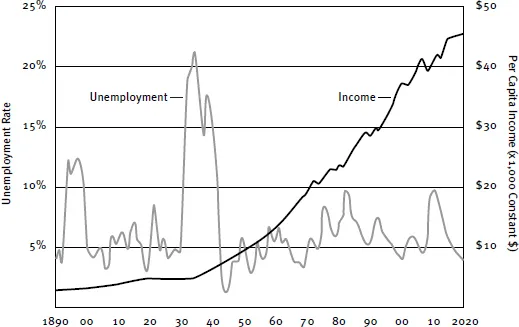

We know two things about the effect of the myriad technological changes over the past 130 years. The first is that continual and often profound advances in labor-saving productivity have boosted the economy so much that per capita wealth has reached unprecedented heights. The second is that despite all that “labor saving,” about 95% of willing and able people have, on average, continued to be employed. In other words, the unemployment rate has remained essentially unchanged at about 5% for all of those 130 years, episodically fluctuating due to cyclical recessions. (See Figure 3.)

If labor-saving technology were a net job destroyer, the unemployment rate should have been growing inexorably over history. But it hasn’t. MIT economist David Autor has been particularly eloquent on the apparent paradox of more employment despite unrelenting advances in labor-reducing technologies, observing that, with regard to the prospects for employment growth, “the fundamental threat is not technology per se but misgovernance.”

Figure 3. 130 Years of U.S. Economic Growth

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Of course, where and how most people are employed has changed. Farming, the most commonly noted example of vanishing employment, accounted for 40% of jobs in the pre-industrial era, compared to only 2% today. In the 1960s, the early days of modern automation saw a rapid decline in automobile-manufacturing jobs, despite the huge boom in automakers’ output. Consider a more recent example, the 1976 introduction of a practical word processor by Wang Laboratories. (Wang invented modern word processing and utterly dominated that market into the early 1980s but was unable to navigate the creative destruction of the burgeoning PC industry, filing for bankruptcy in 1992.) Word processing quickly supplanted the old corporate “typing p...