![]()

FOUR

The Old Simplicity That Worked

THE NEW MYTHOLOGY of La Raza taught in our colleges and universities goes something like this: California was and is an utterly racist state. Its myriad of laws and protocols stymied Mexican aspirations for a century and a half until the rise in the 1970s of militant interest groups—MEChA (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán), MAPA (Mexican-American Political Association), the United Farm Workers and La Raza studies departments everywhere. They alone finally, and only through protest, agitation and occasional violence, have just started to change the complexion of California by insisting on more balanced and sensitive educational programs, coupled with a vast safety net of state assistance and federal affirmative action preferences to redress past injustices. All this was in rightful recompense for the theft of California from Mexico. Under this regime—intellectual and literal—today’s massive illegal immigration is seen as just deserts in returning the American Southwest to its proper cultural foundations.

What has been the result of la causa? Has the lot of Hispanics—gauged by graduation rates from high school, percentages with college degrees, per capita crime statistics vis-à-vis whites and Asians—improved through these efforts to renew ethnic pride and force society to recognize past Chicano icons from Joaquín Murrieta to Caesar Chavez?

dp n="103" folio="76" ?Unfortunately, nearly the opposite is true. Three decades after the rise of the new militancy and separatism, along with unchecked immigration, Hispanics have the highest dropout rates from high school and the lowest percentages of bachelor’s degrees of any ethnic group in the state. For all the good intentions, outreach programs, city-sponsored Cinco de Mayos, Caesar Chavez state holidays and eponymous boulevards and billions of dollars in entitlements, the government—alas!—apparently does not have the power to create instantaneous parity by fiat. Indeed, in our collective efforts to be angelic we can sometimes be devilish by establishing the principle that the state is responsible for an individual’s success or failure.

The key achievement of all these militant groups was the promulgation of a partial truth, which by its very incompleteness became part of today’s Big Lie. Racism, discrimination, labor exploitation—these and more, of course, have been the burdens of the Mexican-American experience. They are also universal pathologies, and quite predictable given the peculiar relationship between a vast democratic and capitalist American nation and an autocratic, economically backward Mexico. But instead of being pondered in that light, these shortcomings are defined as uniquely the sins of white Americans.

The result of the whitewashed new history is that Aztec cannibalism and human sacrifice (especially at the dedication of the great pyramid of Huitzilopochtli in 1487) on a scale approaching the daily murder rate at Auschwitz are seldom discussed as a part of the Mexican past. While Cortés is loudly condemned, we do not hear that the Tlaxcaltecs and other tribes considered the Europeans saviors rather than enslavers. Terrorist organizations of the late nineteenth century like the Gorras Blancas and the Mano Negra are romanticized. The everyday killer Joaquín Murrieta becomes a modern-day Robin Hood who acted on behalf of his people. Endemic and historic Mexican discrimination—either on the basis of skin color (zambos or negras) or class (surrumatos)—is passed over. We are not often told of the racist, anti-Semitic and essentially fascist Sinarquismo movement of the early twentieth century, which favored both Prussian militarism and later German Nazism and claimed half a million supporters in Mexico and thousands north of the border. Reies López Tijerina has made a comeback, a popular folk icon in my college days, with his silly lawsuits about reclaiming “Chicano land” from present-day New Mexicans, including efforts to annex the Kit Carson National Forest to help create a vast racial state of “Aztlan.” Yet rarely do the commentators who have resurrected Tijerina for their pantheon of brown heroes point out that his broadsides were racist to the core and laced with anti-Semitism. Few today discuss how the UFW failed because of its corruption and misappropriation of workers’ funds—and its often bizarre antics such as forcing employees to undergo Synanon-inspired coercive training.

Mexican pathology is ignored in a monolithic caricature of the often heartbreaking history of the border, and so too are the early American efforts at redressing racism: the California Mexican Fact-Finding Committee, the state high court’s reversal of the Sleepy Lagoon murder case, and the efforts of Anglos like Carey McWilliams and Alice Greenfield to champion Mexican causes. We know that easy therapy rather than complex tragedy brings dividends under the present system of racial antagonism in our universities, but does it bring college graduation rates above 7 or 8 percent as well? The terrible suspicion remains that by not emphasizing and promoting traditional education to young Latinos—broad classes in history, logic, philosophy, Western civilization, literature and classics—Chicano leaders ensure a constituency that simply does not possess the learning to question the one-dimensional history and cardboard-cutout heroes and villains that these leaders force-feed them.

Most past segregation was cultural rather than racial, and thus rarely absolute, since anyone who somehow got education, money and a nice house was accepted as mainstream. But even forty years ago there was certainly not much institutionalized racism left. My father’s closest friend on the local junior college faculty, Ray Velasco, was a well-respected physics teacher in 1962. Even a small, conservative rural town like Selma was openly even-handed: In 1965 our top drama student in the fourth grade was Hilario Montoya. Our head football coach thirty-five years ago was Mexican-American. My high-school girlfriend, Ellen Martinez, received a full-ride scholarship to UC Santa Cruz in 1971. Our student body president in 1972 was Mexican-American.

At the acme of the La Raza movement of the 1960s and 1970s, so-called Hispanics had been in the mainstream of American life for years and had found their talent widely appreciated by all races—the best-selling recording artists Herb Alpert, Linda Ronstadt, Richie Valens, Freddie Fender and Joan Baez, the mega-stars Anthony Quinn and Ricardo Montalban, the actresses Raquel (Tejada) Welch, Chita Rivera and Rita Moreno, television icons like Freddie Prinze, Cheech Marin, the great Roberto Clemente, Orlando Cepeda, Tony Oliva and Jim Plunkett, tennis stars such as Rosie Casals, Pancho Gonzales, the famous coaches Tom Flores and Pancho Segura and the golfers Lee Trevino, Chi Chi Rodriguez and Nancy Lopez. And all this success came well before Selena, Fernando Valenzuela and Jennifer Lopez, and without the need of activists like Luis Valdez or Corky Gonzales. Most Americans did not know whether such heroes were Cuban, Puerto Rican or Mexican—and didn’t much care, inasmuch as they were interested in talent, not race.

Hispanics were not always commensurately represented in all American institutions, but notable examples like those above could be multiplied ad infinitem, suggesting that roadblocks were not legal or institutional, but the inevitable social prejudices typical of dominant cultures the world over, which tend to react against their minorities (though elsewhere with autocratic government sanction that thwarts the possibility of amendment by a maturing and more tolerant citizenry). So when today’s social critics talk of segregated swimming pools, race wars, and a scary atmosphere for Mexicans akin to the Deep South of segregation days, they are largely talking of a time long before Desi Arnaz and Jose Ferrer.

dp n="106" folio="79" ?Until 1970, California dealt with rising Mexican immigration the way it handled the lesser influx of Asians, Sikhs, Armenians and all other mass arrivals of immigrants—with rather unapologetically coarse efforts to insist on assimilation. Behind such a one-dimensional policy there were simplistic but unmistakable assumptions about the immigrant: he was here to stay and become an American, not to go back and forth between the old and the new country. He was to become one of us, not we one of him. He was here because he chose to be here, and so was required to learn about us, not we about him.

An underlying supposition in that rather unsophisticated thinking was the prime theorem: the United States is a place far superior to Mexico. Otherwise the immigrant would have stayed put and we would instead have joined him, and thus we would have been his guests there, rather than his hosts here. A corollary was no less important in the mind of the Californian: if we changed so as to accommodate the Mexican alien, then logically he would have no need to come here, since he was voting with his feet to reject Mexican culture, not replicate it. As a Mexican friend admitted to me in a moment of candor, “If you let us make California into Mexico, we will just go to Oregon. If we turn Oregon into Mexico, we’ll stampede our way into Washington. If we turn Washington into Mexico, we’ll sneak into Canada.” What he meant, I think, is that the preservation of American society in its present form—democracy, freedom, uncensored media, diversity in politics, religion and ethnicity, open markets, private property, a vibrant middle class, secular government, civic and judicial audit and more—was attractive to brave Mexicanos stuck in Mexico. They saw America as antithetical to their homeland, and thus their last and only hope.

What was all this chauvinistic and self-acclaimed sense of “superiority” of the United States over Mexico really about? Surely it was not based on racial or genetic pseudoscience, for even racist Californians conceded that many Mexican immigrants, against great odds, soon found parity in every sense with native Californians. Rather the difference was empirically based and multifaceted—legal, economic, religious, historical, cultural and political. Our courts, it was once agreed, were less likely to be corrupt and tended to be systematic and public, not secretive, haphazard and capricious. Our police could be corrupt, but petty bribery was the exception, not the rule, and they did not assassinate reformers with regularity and impunity. There was nothing quite like the mordida in America—the “bite” put on citizens by every government official; those caught taking money were usually shamed and retired or jailed. Our police today are not escorting cocaine dealers and using squad cars to provide security for heroin smugglers on a regular basis.

Our religions were diverse—from eccentric Christian fundamentalists and persecuted Mormons to almost secular Unitarians and Congregationalists—not monolithic parishes. The many branches of Protestantism taught various and sometimes quite contrary doctrines concerning God’s grace in this world and the next. Catholicism was more likely to suggest that the ills and inequities of this world would be redressed in the next; in the days before liberation theology, the grasping rich would get their due when they faced God, rather than be held accountable in the present. Under the monopoly of the conservative Catholic Church in Mexico, an entire culture was taught that sex was for procreation, and the more children, the more souls that could be saved. In contrast, the American Protestant tendency was to regard many offspring as requiring too much time and investment from parents, siblings and society at large—an idea that Catholics considered silly and selfish as well as blasphemous.

According to the educational theory that once held sway, America was the creation of Jefferson, Hamilton, Franklin and Adams; Mexico was the legacy of Hernan Cortés and Pedro Alvarado. Pilgrims were not the same as conquistadors, or so our teachers in their pride maintained. We broke away from liberal reforming British parliamentarians; Mexico much later and with more difficulty separated from a more authoritarian Spanish monarchy. North America was opened to mass immigration; Spain tried to keep all but the Spanish out of Latin America. We were a temperate climate; much of Mexico was nearly tropical. We kicked the English and French out early; Mexico had Spanish and French in their country even in the nineteenth century. American settlers from all over Europe swarmed into a largely uninhabited, but Mexican, Southwest; adventurous Mexican families and homesteaders in covered wagons did not then venture into a largely uninhabited Oregon, Montana and Wyoming. We fought Germans; Mexico intrigued with them. American society at its best was a society of three classes, not two; in Mexico it was mostly a war between campesinos and their patrons, as society from the very beginning of the Spanish conquest was to be defined as the private property of the elite hidalgos and caballeros.

Ours was not so much a patriarchal society, at least in comparison with Latin America or the Arab world. Women were more visible, often worked outside the home, and were active in protests; not so much in Mexico, at least in times of peace. In the United States, private property, deeds and title searches were de rigueur; the rule of property law was not so sacrosanct in Mexico. A man finding his newly built house on someone else’s lot made headlines in America; in Mexico it raised not an eyebrow. Florida, a long peninsula with an inhospitable climate, was settled and its swamps drained as it became a successful multiracial state; Baja California, about the same size and shape and also blazing hot, until recently remained mostly a parched wasteland.

There was no siesta in America; more likely you ate your fatty foods while driving to and from work. Various strains of our heritage, some of them pernicious and neurotic—from the WASP ethic to German Mennonite and Scandinavian habits of constant work—made us pay more attention to our jobs and income than to our families and recreation. Americans, it seemed, lived to work; Mexicans worked to live. All that and more made America, rather than Mexico, an often cut-throat economic powerhouse, where the system protected capital and property, the government dispensed largess at the will of the people, and a person was judged on his performance at making money, not his class, parentage, race or religion.

If you wanted to retire, relax and be accorded status and privilege for being older, refined and male, then Mexico just might be a better place than America. But if you were Irish, Japanese, Korean, African-American, Indian, Muslim or Jehovah’s Witness, and wished to work and get rich, then you’d do far better in America. Any who disagree can ask themselves: how many millions of these have flocked to Mexico, then or now?

The schools, without self-doubt, often rudely and with little apology, dealt head-on with the contradiction that plagues every immigrant to America. Lost in an entirely new world that initially either ignores, oppresses, or discriminates against him, he naturally tends to romanticize the distant culture that pushed him into exile in the first place. I do not know whether my early teachers were conscious of such human subtleties, or aware that an excess of deference can encourage disdain rather than gratitude, that newfound affluence can create envy, and that every majority culture—even one that has recently arrived from Mexico and established an ethnic enclave in a small rural California town—tends to ostracize a minority. Yet these were problems and paradoxes that our instructors sought to resolve one way or another. They seemed to know that the Mexican immigrant could and should retain a pride in his ethnic heritage—to be expressed in music, dance, art, literature, religion and cuisine only—while being mature enough to see that the core political, economic and social values of his abandoned country were to be properly and rapidly forgotten. In my hometown the idea was to turn Mexicans into Selmans. And yet, in accomplishing this delicate task, our grammar school teachers of the 1950s and 1960s, most with degrees from normal schools in Texas and Oklahoma, knew far better the fundamental differences between a flourishing multiracial society and a failed and fractious multicultural quagmire than do our present Ph.D.s from Stanford and Berkeley.

dp n="110" folio="83" ?On “Old Country” day for “show and tell” we all brought in our family’s native dress, food and books to class—hardly a diverse exercise when well over 90 percent of the students at Eric White Elementary School were from Mexico. The student presentations were one-dimensional and completely predictable, as were the teachers’ evaluations; indeed, today such a response would earn immediate dismissal for the teacher and hours of therapeutic counseling for the aggrieved students.

The Mennonite Eric Scheidt once showed us his family’s East Prussian Bible and even spoke a few words of German for us—as he was politely reminded how lucky his parents were to be here rather than being caught in Hitler’s Germany. My twin brother and I brought Swedish rye crackers, a straw dahla horse and pictures of Vikings; but we were hurt when Mr. Payne remarked that Sweden was neutral in World War II. We replied that all second-generation Swedish Hansons in four families sent their only sons to World War II, in which all saw combat and not all survived—a desperate effort on the part of ten-year-olds to establish their patriotic fides. The onus was on us to prove our American credentials, and we found little empathy by claiming to be Swedes and absolutely no guilt to be tapped among our teachers for their being somewhat less ambiguously American.

All of us, but the vast Mexican majority in particular, rolled our eyes and were nauseated when Margaret Olsen went on and on about Denmark, claiming that Copenhagen was cleaner than Los Angeles and that Danes were the world’s finest craftsmen. We put up with her silly handmade Danish dress, but deeply resented the idea that anything important in Denmark could be better than anything unimportant here. Why else, we wondered, would her parents have come here in the first place—and as late as 1940, no less? But of course, almost every other class presentation was Mexicaninspired—piñatas, lore about Pancho Villa, the glories of the Mexican saints—and thus just as brutally reinterpreted by our teachers as interesting artifacts of a foreign culture, but hardly the building blocks of a truly lawful and humane society such as our own.

dp n="111" folio="84" ?Again, the paradoxical mentality of the immigrant was not politely ignored and certainly not assuaged, as it would be today, but rather directly assaulted. The unvoiced assumption—a formulation of classic know-nothingism—resonated with us: If it is really so good over there, why don’t you go back? Was this an exercise in American exceptionalism? Absolutely. Did our teachers lay the foundations for later chauvinism that might manifest itself collectively in what is now derided as American “unilateralism” on the world stage? Perhaps. But did the relegation of cultural diversity to the realm of the private and familial rather than the public and official encourage divisiveness and tension? Hardly at all.

The goal of assimilation that was once the standard, if unspoken orthodoxy in our schools and government is now ridiculed as racist and untrue. The result is that the very idea of both Mexico and America is changing, as is the experience of the immigrant. Instead of growing more distant, a romanticized Mexico is kept closer to the heart of the new arrival—thus erecting a roadblock on his journey to becoming an American. Those who die as Mexicans in California have sought neither to become citizens of the United States nor to return to Mexico. As a local columnist for our paper recently described their nether world: Pensaban que se iban a ir patras (“They thought they would go back to their home”). Apparently he was sad that those who fled Mexico always nostalgically promised to go back, yet eventually died in the United States.

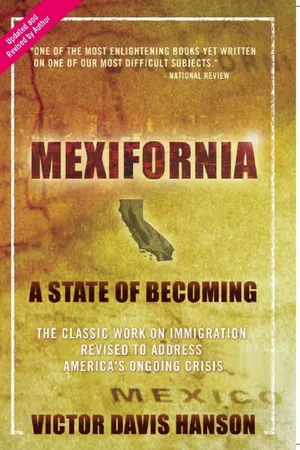

Sociologists, the media and university activists now envision balkanized enclaves in America, assuring us that retaining the umbilical cord of Mexican culture is not injurious. Instead, we are for the first time creating a unique culture that is neither Mexican nor American, but something amorphous and fluid—the dividend of the multicultural investment. Whether you break the law to reach California or immigrate legally, it makes little difference in determining how well you drive, whether you send your kids to college, or whether you draw on the public services of the state. The bien pensant punditry—which lives exclusively north of the border, most often in white suburbs that are not integrated—will rush to add that southern California and northern Mexico will soon create their own regional civilization, perhaps even their own language and culture. An offspring not wholly of either parent will arise, and this Califexico, Mexifornia or Republica del Norte is not a “bad” thing at all, but something which, if not exactly advantageous, at least is inevitable.

After all, these pundits note, two thousand maquiladoras—American corporations with Mexi...