eBook - ePub

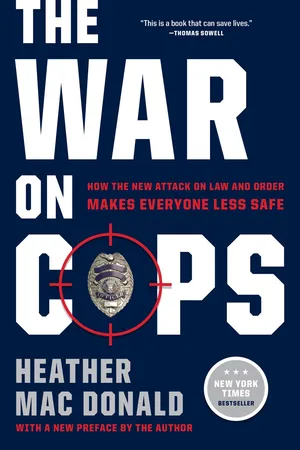

The War on Cops

How the New Attack on Law and Order Makes Everyone Less Safe

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

New York Times Best Seller

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The War on Cops by Heather Mac Donald in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Civil Rights in Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Burning Cities and the Ferguson Effect

The August 2014 police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, spawned a narrative as stubborn as it was false: Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson had allegedly shot the 18-year-old “gentle giant” in cold blood while the latter was pleading for his life, hands raised in surrender. After Brown’s death, rioters torched and looted Ferguson businesses. The facts were that Brown, a budding criminal who weighed nearly 300 pounds, had punched Wilson in the face, tried to grab Wilson’s gun, and charged at him, leading Wilson to fire in self-defense.

In the months that followed, the lie that Brown had died in a racially motivated police execution was amplified by the media, college presidents, and the left-wing political class. The newly formed Black Lives Matter movement promoted the notion that black American males were being hunted down and killed with impunity by renegade white police officers. Eric Garner, who had died after a forceful police takedown on Staten Island, New York, was added to the list of martyrs to racist police brutality.

Riots broke out in Ferguson for a second time in November 2014 when a grand jury declined to indict Wilson for Brown’s death. Black Lives Matter protests grew ever more virulent as a second myth took hold: that the American criminal-justice system is rigged against blacks. In December 2014, Ismaaiyl Abdullah Brinsley assassinated Officers Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos of the New York Police Department in retaliation for the deaths of Garner and Brown. Police actions in minority neighborhoods became increasingly tense; suspects and bystanders routinely challenged officers’ lawful authority.

Slandered in the media and targeted on the streets, officers reverted to a model of purely reactive policing that had been out of vogue since the early 1990s. The inevitable result? Violent crime surged in city after city, as criminals began reasserting themselves—a phenomenon that I and others controversially described as the “Ferguson effect.” President Barack Obama’s FBI director, James Comey, confirmed the Ferguson effect in a speech at the University of Chicago Law School in October 2015. The rise in homicides and shootings in the nation’s 50 largest cities was likely due to the “chill wind blowing through American law enforcement over the last year,” he said, a wind that “is surely changing behavior.” Sadly, the president himself contributed directly to that chill wind against the nation’s police forces.

1

Obama’s Ferguson Sellout

On November 24, 2014, President Obama betrayed the nation. Even as he went on national television to respond to the grand-jury decision not to indict Officer Darren Wilson for fatally shooting 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, the looting and arson that had followed Brown’s shooting in August were being reprised, destroying businesses and livelihoods over the next several hours. Obama had one job and one job only in his address that day: to defend the workings of the criminal-justice system and the rule of law. Instead, he turned his talk into a primer on police racism and criminal-justice bias. In so doing, he perverted his role as the leader of all Americans and as the country’s most visible symbol of the primacy of the law.

Obama gestured wanly toward the need to respect the grand jury’s decision and to protest peacefully. “We are a nation built on the rule of law. And so we need to accept that this decision was the grand jury’s to make,” he said. But his tone of voice and body language unmistakably conveyed his disagreement, if not disgust, with that decision. “There are Americans who are deeply disappointed, even angry. It’s an understandable reaction,” he said.

Understandable, so long as one ignores the evidence presented to the grand jury. The testimony of a half-dozen black observers at the scene had demolished the early incendiary reports that Wilson attacked Brown in cold blood and shot Brown in the back when his hands were up. Those early witnesses who had claimed gratuitous brutality on Wilson’s part contradicted themselves and were, in turn, contradicted by the physical evidence and by other witnesses, who corroborated Wilson’s testimony that Brown had attacked him and had tried to grab his gun. (Minutes before, the hefty Brown had thuggishly robbed a diminutive shopkeeper of a box of cigarillos; Wilson had received a report of that robbery and a description of Brown before stopping him.) Obama should have briefly reiterated the grounds for not indicting Wilson and applauded the decision as the product of a scrupulously thorough and fair process. He should have praised the jurors for their service and courage in following the evidence where it led them. And he should have concluded by noting that there is no fairer criminal-justice system in the world than the one we have in the United States.

Instead, Obama reprimanded local police officers in advance for an expected overreaction to the protests: “I also appeal to the law-enforcement officials in Ferguson and the region to show care and restraint in managing peaceful protests that may occur. . . . They need to work with the community, not against the community, to distinguish the handful of people who may use the grand jury’s decision as an excuse for violence . . . from the vast majority who just want their voices heard around legitimate issues in terms of how communities and law enforcement interact.”

Such skepticism about the ability of the police to maintain the peace appropriately was unwarranted at the time and even more so in retrospect; the forces of law and order didn’t fire a single shot. Nor did they inflict injury, despite having been fired at themselves. Missouri’s governor, Jay Nixon, was under attack for days for having authorized a potential mobilization of the National Guard—as if the August rioting didn’t more than justify such a precaution. Any small-business owner facing another wave of violence would have been desperate for such protection and more. Though Nixon didn’t actually call up the Guard, his prophylactic declaration of a state of emergency proved prescient.

Obama left no doubt that he believed the narrative of the mainstream media and race activists about Ferguson. That narrative held that the shooting of Brown was a symbol of nationwide police misbehavior and that the August riots were an “understandable” reaction to widespread societal injustice. “The situation in Ferguson speaks to broader challenges that we still face as a nation. The fact is, in too many parts of this country, a deep distrust exists between law enforcement and communities of color.” This distrust was justified, in Obama’s view. He reinvoked the “diversity” bromide about the racial composition of police forces, implying that white officers cannot fairly police black communities. Yet some of the most criticized law-enforcement bodies in recent years have, in fact, been majority black.

“We have made enormous progress in race relations,” Obama conceded. “But what is also true is that there are still problems, and communities of color aren’t just making these problems up. . . . The law too often feels like it’s being applied in a discriminatory fashion. . . . [T]hese are real issues. And we have to lift them up and not deny them or try to tamp them down.”

To claim that the laws are applied in a discriminatory fashion was a calumny, unsupported by evidence. For the president of the United States to put his imprimatur on such propaganda was bad enough; to do so following a verdict in so incendiary a case was grossly irresponsible. But such partiality followed the pattern of this administration in Ferguson and elsewhere, with Attorney General Eric Holder prematurely declaring the Ferguson police force in need of wholesale change and President Obama invoking Ferguson at the United Nations as a manifestation of America’s ethnic strife.

The wanton destruction that followed the grand jury’s decision was overdetermined. For weeks, the press had been salivating at the potential for black violence. The New York Times ran several stories a day, most on the front page, about such a prospect. Media coverage of racial tension portrayed black violence as customary, and riots as virtually a black entitlement.

The press dusted off hoary tropes about police stops and racism, echoing the anti-law-enforcement agitation and the crusade against “racial profiling” of the 1990s. The New York Times selected various features of Ferguson almost at random and declared them racist, simply by virtue of their being associated with the city where Michael Brown was killed (a theme that Chapter 2 examines further). A similar conceit emerged regarding the grand-jury investigation: innocent or admirable aspects of the prosecutor’s management of the case, such as the quantity of evidence presented, were blasted as the product of a flawed or deliberately tainted process—so desperate were the activists to discredit the grand jury’s decision.

This kind of misinformation about the criminal-justice system and the police can only increase hatred of the police. That hatred, in turn, will heighten the chances of more Michael Browns attacking officers and getting shot themselves. Police officers in the tensest areas may hold off from assertive policing. Such de-policing will leave thousands of law-abiding minority residents who fervently support the police ever more vulnerable to thugs.

Obama couldn’t have stopped the violence in Ferguson with his address to the nation. But in casting his lot with those who speciously impugn our criminal-justice system, he increased the likelihood of more such violence in the future.

2

Ferguson’s Unasked Questions

Press reports on the Ferguson “unrest,” as the media prefer to call such violence, quickly began to reveal an operative formula: select some aspect of the city’s political or civic culture; declare it racist by virtue of its association with Ferguson; disregard alternative explanations for the phenomenon; blame it for the riots. Bonus move: generalize to other cities with similar “problems.” By this process, the media could easily reach predetermined conclusions.

For example: Ferguson’s population is two-thirds black, but five of its six city council members are white, as is its mayor. Conclusion: this racial composition must be the product of racism. Never mind that blacks barely turn out to vote and that they field practically no candidates. Never mind that the mayor ran for a second term unopposed. Is there a record of Ferguson’s supposed white power structure suppressing the black vote? None has been alleged. Did the rioters even know who their mayor and city council representatives were? The press didn’t bother to ask. It only saw an example of what was imagined to be a disturbingly widespread problem. In a front-page story complete with a sophisticated scatter-graph visual aid, the New York Times summed up the problem: “Mostly Black Cities, Mostly White City Halls.”

Another example: Ferguson issues fines for traffic violations, and 20 percent of its municipal budget comes from such receipts. If people with outstanding fines or summonses don’t appear in court, a warrant for their arrest is issued. Conclusion: this is a racist system. The city is deliberately financing its operations on the backs of the black poor. The only reason that blacks are subject to fines and warrants, according to the media, is that they are being hounded by a racist police force. “A mostly white police force has targeted blacks for a disproportionate number of stops and searches,” declared Time (September 1). What was the evidence for such “targeting”? Time provided none. Might blacks be getting traffic fines for the same reason that whites get traffic fines—because they broke the law? The possibility was not considered.

The most frequently summonsed traffic offense is driving without insurance, according to an “exposé” of Ferguson’s traffic-fine system by the New York Times. Perhaps the paper’s editors would be blasé about being hit by an uninsured driver, but most drivers would be grateful that the insurance requirement is being enforced. Might poor blacks have a higher rate of driving without insurance than other drivers? Not relevant to know, apparently.

The next highest categories of driving infraction are blasting loud music out your car and driving with tinted windows. If you attend police-and-community meetings in poor areas, you will regularly hear complaints about cars with deafening sound systems. Should the police ignore such complaints? Are they ignoring similar complaints in white areas because they want to give whites a pass? Do Ferguson’s white and black drivers blast loud music from their cars at the same rate? We never learn. Tinted windows pose a possibly lethal threat to the police during traffic stops, since they prevent officers from assessing the situation inside the car before approaching. Ignoring this infraction puts officers’ lives at risk. Should the police nevertheless do so? Such is the implication, if doing so would mean fewer fines for black motorists. The New York Times quotes a victim of the “racist” Ferguson traffic-enforcement system who was fined for driving without a license. Why was his license suspended? Was he driving drunk? Did he hit someone? We will never know. What is the crime rate in the black areas of Ferguson? That is also something that the mainstream press is not interested in finding out.

The most ubiquitous “Ferguson is racist” meme was that the city’s police force is too white. Four of Ferguson’s 53 officers are black. This imbalance, it was suggested, must be the result of racism and must itself cause racist enforcement activity. How many qualified black applicants have been rejected after applying to join the Ferguson police force? Not an interesting question, evidently.

The “too-white police force” meme, which the New York Times generalized into another front-page article (“Mostly White Forces in Mostly Black Towns,” September 10), complete with another impressive set of graphs, is of particular interest in light of the federal government’s investigation of New York City’s sprawling Rikers Island jail complex. In August 2014, the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York issued a report denouncing the “deep-seated culture of violence” among Rikers corrections officers toward adolescent inmates. He accused guards of handcuffing juvenile inmates to gurneys and beating them. Rikers had been bedeviled by such claims of officer abuse of inmates for years, but the resulting problem for the “abusive white cops” meme is that the Rikers officer force is about two-thirds black. (New York’s population is 23 percent black, but no one has complained about the racial imbalance among Rikers guards.)

Also in August, the Detroit Police Department emerged from 11 years of federal oversight for alleged abuse of civilians, including a pattern of unjustified shootings. The Detroit force, too, is about two-thirds black. In 2012, after a two-year investigation for a pattern of civil rights violations, the U.S. Justice Department imposed on the New Orleans Police Department an exceptionally expansive consent decree—a nominally consensual agreement overseen by a court—to try to rein in the alleged unconstitutional behavior of its officers, the majority of whom are black.

Now perhaps these civil rights allegations against these majority black forces are trumped up. But if so, perhaps similar allegations against majority white forces are, too. Or maybe the race of officers has little to do with whether they can police fairly.

As the grand jury was deliberating over whether to charge Darren Wilson with murder for shooting Michael Brown, cops were being shot at in and around Ferguson. Authorities hastily discounted any connection with the ongoing protests. Death threats against police officers multiplied. Even after the grand jury found insufficient grounds to indict Officer Wilson, the media kept flogging a story that was driven by facile, and ultimately dangerous, preconceptions.

3

Finding Meaning in Ferguson

Shortly after President Obama’s speech on the grand-jury decision, the New York Times officially pronounced on the “meaning of the Ferguson riots.” A more perfect example of what the late Daniel Patrick Moynihan called “defining deviancy down” would be hard to find. The Times’ editorial encapsulated the elite narrative around the shooting of Michael Brown and the mayhem that twice followed it.

The Times could not bring itself to say one word of condemnation against the savages who self-indulgently destroyed the livelihoods of struggling entrepreneurs and their employees in Ferguson, Missouri. The real culprit behind the riots, in the Times’ view, was not the actual arsonists and looters; it was Robert McCulloch, the county prosecutor who presented the shooting of Brown by Officer Darren Wilson to a St. Louis County grand jury. After hearing three months of testimony, the grand jury decided not to bring criminal charges against Wilson. The Time...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface to the Paperback Edition

- Introduction: The Policing Revolution, Crime, and the Anti-Law-Enforcement Movement

- Part One: Burning Cities and the Ferguson Effect

- Part Two: Handcuffing the Cops

- Part Three: The Truth About Crime

- Part Four: Incarceration and Its Critics

- Index