![]()

Part I: Israeli Independence, Palestinian Catastrophe

We have forgotten that we have not come to an empty land to inherit it, but we have come to conquer a country from people inhabiting it.1

Moshe Sharett, Israel’s second prime minister

‘Ben-Gurion was right …Without the uprooting of the Palestinians, a Jewish state would not have arisen here.’2

Benny Morris, Israeli historian

In August 1897, in the Swiss city of Basle, a meeting took place that would have profound and disastrous consequences for the Palestinians – though they were not present at the event, or even mentioned by the participants. The First Zionist Congress, the brainchild of Zionism’s chief architect Theodor Herzl, resulted in the creation of the Zionist Organization (later the World Zionist Organization) and the publication of the Basle Programme – a kind of early Zionist manifesto.

Just the year before, Herzl had published ‘The Jewish State’, in which he laid out his belief that the only solution to the anti-semitism of European societies was for the Jews to have their own country. Writing in his diary a few days afterwards, Herzl predicted what the real upshot would be of the Congress:

At Basle I founded the Jewish State. If I said this aloud today, I would be answered by universal laughter. In five years perhaps, and certainly in fifty years, everyone will perceive this.3

Herzl’s Zionism was a response to European anti-semitism and, while a radical development, built on the foundations of more spiritually and culturally focused Jewish settlers who had already gone to Palestine on a very small scale. At the time, many Jews, for different reasons, disagreed with Herzl’s answer to the ‘Jewish question’. Nevertheless, the Zionists got to work; sending new settlers, securing financial support and bending the ear of the imperial powers without whose cooperation, the early leaders knew, the Zionist project would be impossible to realise.

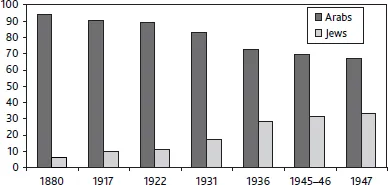

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the population of Palestine was around 4 per cent Jewish and 96 per cent Palestinian Arab (of which around 11 per cent were Christian and the rest Muslim).4 Before the new waves of Zionist settlers, the Palestinian Jewish community was ‘small but of long standing’, and concentrated ‘in the four cities of religious significance: Jerusalem, Safed, Tiberias and Hebron’.5 As new Zionist immigrants arrived, with the help of outside donations, French experts were called upon to share their experience of French colonisation in North Africa.6

An early priority for the Zionists was to secure more land on which to establish a secure, expanded, Jewish community. In 1901, the Jewish National Fund (JNF) was founded, an organisation ‘devoted exclusively to the acquisition of land in Palestine for Jewish settlement’.7 The JNF was destined to play a significant role in the history of Zionism, particularly as the land it acquired, by definition, ‘became inalienably Jewish, never to be sold to or worked by non-Jews’.8

Figure 1 Palestinian population, 1880–1947

Source: Facts and Figures About the Palestinians, Washington, DC:

The Center for Policy Analysis on Palestine, 1992, p. 7.

The land purchased by the JNF was often sold by rich, absentee land-owners from surrounding Arab countries. However, much of the land was worked by Palestinian tenant farmers, who were then forcibly removed after the JNF had bought the property. Thousands of peasant farmers and their families were made homeless and landless in such a manner.9

The Zionists knew early on that the support of an imperial power would be vital. Zionism emerged in the ‘age of empire’ and thus ‘Herzl sought to secure a charter for Jewish colonization guaranteed by one or other imperial European power’.10 Herzl’s initial contact with the British led to discussions over different possible locations for colonisation, from an area in the Sinai Peninsula to a part of modern day Kenya.11 Once agreed on Palestine, the Zionists recognised, in the words of future president Weizmann, it would be under Britain’s ‘wing’ that the ‘Zionist scheme’ would be carried out.12

The majority of British policy-makers and ministers viewed political Zionism with favour for a variety of reasons. For an empire competing for influence in a key geopolitical region of the world, helping birth a natural ally would reap dividends. From the mid nineteenth century onwards, there was also a tradition of a more emotional and even religious support for the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine amongst Christians in positions of influence, including Lord Shaftesbury and Prime Minister Lloyd George.13

Britain’s key role is most famously symbolised by the Balfour Declaration, sent in a letter in 1917 by then Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour to Lord Rothschild. The Declaration announced that the British government viewed ‘with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people’ and moreover, promised to ‘use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object’. At the time, Jews were less than 10 per cent of Palestine’s population.14

In the end, the role of the imperial powers proved crucial. For all the differences between some in the British foreign policy establishment and members of the Zionist movement – as well as the open conflict between radical Zionist terror groups and British soldiers – it was under British rule that the Zionists were able to prepare for the conquest of Palestine. Ben-Gurion once joked, after visiting the Houses of Parliament in London, ‘that he might as well have been at the Zionist Congress, the speakers had been so sympathetic to Zionism’.15

Differences between the Zionist leaders of various political stripes were essentially tactical. As Ben-Gurion explained, nobody argued about the ‘indivisibility’ of ‘Eretz Israel’ (the name usually used to refer to the total area of the Biblical ‘Promised Land’).16 Rather, ‘the debate was over which of two routes would lead quicker to the common goal’. In 1937, Weizmann told the British high commissioner that ‘we shall expand in the whole country in the course of time … this is only an arrangement for the next 25 to 30 years’.17

A LAND WITHOUT A PEOPLE …

There is a fundamental difference in quality between Jew and native.18

Chaim Weizmann, Israel’s first president

The Zionist leadership’s view of the ‘natives’ was unavoidable – ‘wanting to create a purely Jewish, or predominantly Jewish, state in an Arab Palestine’ could only lead to the development ‘of a racist state of mind’.19 Moreover, Zionism was conceived as a Jewish response to a problem facing Jews; the Palestinian Arabs were a complete irrelevance.

In the early days, the native Palestinians were entirely ignored – airbrushed from their own land – or treated with racist condescension, portrayed as simple, backward folk who would benefit from Jewish colonisation. One more annoying obstacle to the realisation of Zionism, as Palestinian opposition increased, the ‘natives’ became increasingly portrayed as violent and dangerous. For the Zionists, Palestine was ‘empty’; not literally, but in terms of people of equal worth to the incoming settlers.

The early Zionist leaders expressed an ideology very similar to that of other settler movements in other parts of the world, particularly with regards to the dismissal of the natives’ past and present relationship to the land. Palestine was considered a ‘desert’ that the Zionists would ‘irrigate’ and ‘till’ until ‘it again becomes the blooming garden it once was’.20 The ‘founding father’ of political Zionism, Theodor Herzl, wrote in 1896 that in Palestine, a Jewish state would ‘form a part of a wall of defense for Europe in Asia, an outpost of civilization against barbarism’.21

Many British officials shared the Zionist view of the indigenous Palestinians. In a conversation, the head of the Jewish Agency’s colonisation department asked Weizmann about the Palestinian Arabs. Weizmann replied that ‘the British told us that there are some hundred thousand negroes and for those there is no value’.22

Winston Churchill, meanwhile, explained his support for Jewish settlement in Palestine in explicitly racist terms. Comparing Zionist colonisation to what had happened to indigenous peoples in North America and Australia, Churchill could not ‘admit that a wrong has been done to those people by the fact that a stronger race, a higher grade race, or, at any rate, a more worldly-wise race, to put it that way, has come in and taken their place’.23

The Zionist movement was passionately opposed to democratic principles being applied to Palestine, for obvious reasons. As first Israeli Prime Minister Ben-Gurion admitted in 1944, ‘there is no example in history of a people saying we agree to renounce our country’.24 At the beginning of British Mandate rule in Palestine, the Zionist Organization in London explained that the ‘problem’ with democracy is that it

too commonly means majority rule without regard to diversities of types or stages of civilization or differences of quality … if the crude arithmetical conception of democracy were to be applied now or at some early stage in the future to Palestinian conditions, the majority that would rule would be the Arab majority …25

As late as 1947, the director of the US State Department Office of Near Eastern and African Affairs warned that the plans to create a Jewish state ‘ignore such principles as self-determination and majority rule’, an opinion shared by ‘nearly every member of the Foreign Service or of the department who has worked to any appreciable extent on Near Eastern problems’.26

THE ‘TRANSFER’ CONSENSUS

‘Disappearing’ the Arabs lay at the heart of the Zionist dream, and was also a necessary condition of...