![]()

1

Endgame Britain? The Four Crises of ‘Anglobalisation’

In the twelve months after the Yes campaign was launched, the UK lost its triple-A credit rating, finalised its humiliating withdrawal from Afghanistan, and saw 350,000 people rely on food banks to stave off hunger. But many analysts cringe at these topics, considering them impertinent to the 2014 debate. Column inches are dedicated to ‘what Scotland thinks’, pouring over the minutiae of voter intentions and the intrigues of party leaders. The debate’s substance, the British state, often disappears in this haze.

Public opinion is crucial, but its terms are not fixed. Rather than treat voters as a passive bundle of neuroses, we should remind them of the urgency of change, addressing the citizen, not the psyche. Otherwise, by focusing on individual impulses, conservative forces will set the agenda and define the meaning of 2014.

Yes supporters tend to downplay the vote’s significance, fearing it will startle potential supporters. But if we tell people they are terrified of change, they will start to believe it. If you fear the unknown, why vote for separation? Instead, we should treat citizens as rational and mature enough to handle the implications of their decision. The stakes are very high, as Scotland’s vote could consign the British state to history. No referendum has ever had such far-reaching consequences. Every four years, we register views on politicians, but how often do we decide the fate of a global power?

Our analysis of independence thus begins with the ideology of Britain today. Fantasies of national destiny are common to all Westminster parties, but they receive little scrutiny. By outlining Britain’s ruling ideas, we expose their ‘nationalist’ core. British politics relies on an imaginary sense of power and purpose; but reality often intrudes, exposing the shabbiness of Westminster’s ambitions. When facts trespass on prevailing assumptions, a crisis results; and UK politics faces crises on many fronts.

Anglobalisation

Britain was the first truly capitalist nation state, and despite its gradual democratisation, its core institutions survived disruptions intact. Unlike European rivals, it escaped convulsions of invasion and revolution for over three centuries. While other states chopped off heads, swung dictators from lampposts, and restructured parliaments, the UK evolved in bits and pieces. Existing elites absorbed democratic challenges with minimal upheaval. Labour sold the welfare state as an extension of the privileges of Empire.

Although the establishment retained its privileges, this did not insulate Britain from wider events. In lieu of radical change, Britain suffered a century-long erosion of power. For most of the 1900s, Westminster contemplated ‘decline’, ceding influence to American and European challengers.

Two issues highlighted Britain’s woes. First, after 1945, Britain surrendered its Empire, pressured from above by the US and from below by anti-colonial uprisings. Preserving a Commonwealth trading area and a Sterling zone slowed, but did not stop, this slump of global ambition. The US quashed an Anglo-French-Israeli invasion of Suez in 1956, proving Britain’s shrivelling relevance. Paralysing conflicts within Britain’s industries during the 1960s and 1970s heightened these problems, leading to the tag ‘the sick man of Europe’. Britain had enjoyed a rapid rise to imperial power and industrial supremacy in the nineteenth century; but in a century it vanished.

Britain’s elites saw waning influence overseas and workers’ strength in industry as two parts of the same problem. Both symbolised decline. This is why British ideology pivots around Margaret Thatcher. Her reign, according to present-day mythology, restored national pride on both fronts. Thatcher identified a common enemy (‘socialism’) both at home and abroad; by declaring war on this rot, she reversed Britain’s malaise and lifted the gloom.

Even critics point to Thatcher’s ‘remarkable achievements’ and the necessity of her reign. As a result, a new post-decline ideology emerged, spanning all sides of Westminster. From sinking the Belgrano to hosting the Olympics, the media proclaims a British resurgence. Tony Blair cast the UK both as a ‘pivotal power’ between Europe and the US, and as ‘cool Britannia’, a trendsetter in fashion and retail. The colonies have gone; but Britain retains its purpose, and its intellectuals celebrate British Civilisation without apologies. Politicians and historians recount the Victorian era as a golden age, with lessons for American statesmen today. ‘We should be proud of our colonial history in Africa,’ Gordon Brown remarked on a trip to Tanzania, ‘the days of Britain having to apologise for its colonial history are over.’1

In common parlance, ‘British nationalism’ refers to little Englanders, xenophobes and the BNP. But this confuses nationalism with defensive parochialism; for the most powerful states, nationalism affirms their right to rule. By this logic, Brown beats Nick Griffin or Nigel Farage as a British nationalist. True, Britain no longer commands other nations; instead, Westminster nationalism declares a continuous bond between the UK and US Empires. Their shared mission is to open closed societies to globalisation: ‘commerce, civilisation and Christianity’, in the words of Scottish explorer David Livingstone. British nationalists see uninterrupted purpose in the Anglophone world, a project to spread civilisation across the globe.

We call this the fantasy of ‘Anglobalisation’, following the Scottish historian Niall Ferguson.2 This word captures both parts of British nationalism: the aristocracy of English-speaking whites, and free market evangelism. Although Ferguson’s rhetoric recalls Tory chauvinism, all major parties in Westminster express similar ideas. This new British nationalism refuses to apologise for the past, and casts itself as a wise counsel to the American ‘colossus’.

By explaining these ideas, we do not excuse them. Britain’s Empire was far from a civilising influence. We refer anyone who doubts this to Mike Davis’s research on ‘late Victorian Holocausts’, free market famines imposed on India and China in the late nineteenth century that killed up to 50 million.3 We could mention the slave trade, Trevelyan’s starving of Ireland, the Bengal famine, torture camps, and many other cruelties inflicted under the banner of ‘civilisation’. Alas, we do not have the space to explore the details of Britain’s crimes. But they are not ancient history or irrelevant to the debate. Gulags rendered ‘Communism’ unspeakable; the Holocaust did the same for fascism. Britain committed parallel acts in a parallel era, but nobody apologises; instead, the Empire’s achievements are heralded as exemplars of civilised rule.

In Chapter 2, we will examine British nationalism in greater depth. In this chapter, we want to confront the myth of post-Thatcher revival. Each proposal to ‘fix’ British decline, rather than adjust and transform Westminster’s raison d’être, generates new imbalances. The product of these failed fixes is the constitutional crisis of 2014.

Imperial Crisis

As of 1909, the British Empire spanned a quarter of the world’s surface, comprising 12.9 million square miles of territory and 444 million subjects. Including the oceans, Britain ruled 70 per cent of the planet.4 Circa 1970, a small fraction remained. Although Britain intervened in ex-colonies such as Uganda, where it patronised Idi Amin, and in Northern Ireland, its sovereignty ran to a few islands. The Suez crisis was as damaging for British imperialism as Vietnam was for the Americans; for at least a generation, Westminster laboured under a ‘Suez syndrome’. A significant bloc of Tory opinion, led by Enoch Powell, urged Westminster to adjust to the loss of Empire by retreating into insular English nationalism.

Thatcher’s role was to mix Powell’s English individualism with a muscular role for Britain in world affairs. When the Argentinian junta claimed sovereignty over the Falklands, her immediate response was to dispatch the naval fleet. Britain, Thatcher insisted, would not take impertinence from trumped-up generals. The affair helped Westminster overcome its Suez syndrome by showing that Britain could move unilaterally to defend its interests.5 It also cemented a new transatlantic alliance with the Reagan administration, spanning the globe from Afghanistan to Chile in a war on socialism in any form.

The crusading US-UK alliance continued after the end of the Cold War. Blair emphasised the UK’s role as ‘deputy sheriff’6 to the US in defending Western values, aiming to fuse Thatcher’s brute force with so-called ‘humanitarian purpose’. His advisers spoke of a ‘post-modern imperialism’ tasked with bringing freedom to the world.7 Blair insisted: ‘We are not a superpower, but we can act as a pivotal partner … a force for good … I believe we have found a modern foreign policy role for Britain.’8

The twin myths of humanitarian intervention and an ethical foreign policy helped to legitimise this benign imperialism. Charity-inclined celebrities such as Bono and Bob Geldof were happy to declare common purpose with US and UK leaders, who were ‘good guys’. Bush and Blair, they insisted, wanted the G8 summit to rid Africa of hunger and disease. Even leaving Iraq aside, this strained credulity. Live Aid in 1985, the pinnacle of rock-star charity, raised £30 million to relieve African poverty. Two months later, the UK government finalised an arms deal with Saudi Arabian dictators worth £43 billion, more than 1,400 Live Aids.9 Appeals to the moral character of world leaders can mask the systemic nature of violence.

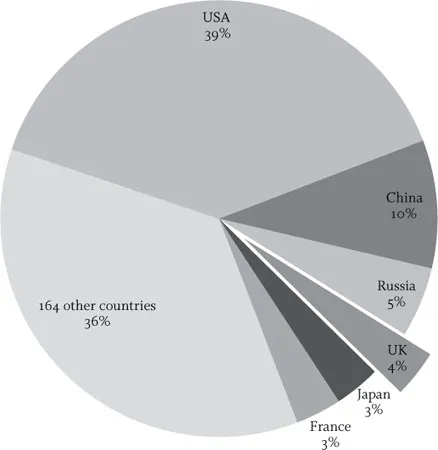

But when Blair insisted that the UK directed American power to moral ends, he had many accomplices in the media. John Pilger, Seumas Milne and Tariq Ali may have queried this Westminster self-image, but there were few other dissenters. Of course, there were sprinklings of truth among the canards: the UK was more than a ‘poodle’ of the US. At the level of diplomacy and, to a degree, of armed force, Britain exercised potent force. Having once ruled the world, the UK is still one of five countries to have a permanent seat on the UN Security Council, along with the US, France, Russia and China. Even so, the term ‘special relationship’ is a Westminster vanity; the US’s total military spending dwarfs all of its rivals put together (see Figure 1.1). Measured by arms superiority, the US surpasses any earlier Empire, even Britain at its peak.

The early years of the War on Terror appeared to cement American command. After 9/11, most agreed that terrorists had wronged America, and gave Washington leeway to exact vengeance, overriding international law. Only a few broke with conformity and identified the roots of 9/11 in American foreign policy. Afghan casualties, ‘collateral damage’ of the war, served as proof that justice requires sacrifices. The radical Left, and the odd Establishment deviant, opposed the war, but they were minorities; even the Scottish Nationalists praised the sincerity of Western intentions in Kabul.

The great gamble was to extend this ideological success to Iraq. Tony Blair knew the impact of the invasion would define the next generation of global politics. In the run-up to war, on 18 March 2003, he faced his critics in the Commons:

The outcome of this issue will now determine more than the fate of the Iraqi regime and more than the future of the Iraqi people … It will determine the way Britain and the world confront the central security threat of the 21st century; the development of the UN; the relationship between Europe and the US; the relations within the EU and the way the US engages with the rest of the world. It will determine the pattern of international politics for the next generation.10

Figure 1.1 Percentage of world military expenditure in 2012 by six countries with highest expenditure

Source: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) www.sipri.org

Today, the anti-Iraq War movement has changed the debate on American power. But in 2003, the establishment still accepted the framework of the US’s good intentions. All Westminster parties agreed that Saddam’s WMDs were the principle danger to world peace, and required swift action. Anyone who mentioned oil interests, queried WMDs, or cited Israel’s nuclear bombs was labelled a conspiracy theorist or a lunatic.

This did not prevent many MPs voting against invasion, but the Lib Dems and other opponents still upheld the mission’s sincerity, never questioning Bush’s crusade against terrorism, chemical weapons and evil dictators. Their aim was a multilateral compromise and a second UN resolution. Those who moved outside this frame, such as Tony Benn and George Galloway, faced vicious character assassinations. ‘Legitimate’ opponents of the war preserved polite fictions of humanitarian purpose.

However, Blair’s omen proved fatally correct: Iraq really did redefine global politics, even more than he imagined. After a decade of occupation, no one accepts US good intentions a priori, at least not without significant qualifications. Few doubt the anti-war version of events: that the neocons aimed to capture Iraq’s oil ahead of Russia and China, and to strengthen Israel. Even Alan Greenspan, former head of the US Federal Reserve, admits as much: ‘I am saddened,’ he wrote, ‘that it is politically inconvenient to acknowledge what everyone knows: the Iraq war is largely about oil.’11

Like Vietnam and Suez before it, Iraq looms over any US-UK mission. Opinions also shifted on Afghanistan, which morphed from a good war into a graveyard. The US’s aerial power can destabilise ‘rogue states’ and ‘evil dictators’ with ease, but it could not command a restless population allied to a determined guerrilla resistance.

The UK presented itself as the conscience of US power, drawing on its colonial experience of building local alliances to police civilian populations. But ‘divide and rule’ in Iraq and Afghanistan did not prove to be a pacifying principle. On the contrary, it prompted vicious sectarian reprisals and open civil war. The persistent conceit of post-Thatcher Westminster – that a US-UK alliance could bind morals to muscle – is exposed as another bromide of imperial power.

As a result, post-Iraq Britain lacks clear purpose. The US has moved on under Obama, but still asserts remote influence in Syria and Pakistan. On Assad, the UK enraged their Washington handlers by voting against military action, the first time Westminster had openly disobeyed American wishes since Suez. This was a bungled miscalculation rather than a deliberate affront, but it highlighted new insecurities about the UK’s vassal role. Britain needs the US far more than vice versa; the White House ...