![]()

1

CHINA AND THE TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY CRISIS

Before 2008, capitalism was celebrated as the best of all possible economic and social systems. It was “the End of History” – “There is no alternative!” The Great Recession of 2008–2009 nearly destroyed the global capitalist economy and brought the era of “the End of History” to an end.

Since then, mass protests and popular rebellions have transformed the political map throughout the world. In Western Europe and North America, growing poverty and mass unemployment led to young people’s political awakening and popular desires for social change. In the Middle East, dictatorial regimes that had lasted for decades were overthrown by popular uprisings. In Latin America, several progressive governments were elected. Cuban socialism began to revive and a successful socialist transition in Venezuela became a possibility. In China, the Maoist New Left became a significant political and intellectual force. For several years, Bo Xilai (who was a member of the Chinese Communist Party’s Politburo) led an economic and social experiment in the Municipality of Chongqing that seemed to provide a viable progressive alternative to the neoliberal capitalist model.

In 2012, Bo Xilai was purged from the Party and later sentenced to life imprisonment ostensibly on the indictment of corruption. In 2013, the new Chinese leadership led by Xi Jinping re-confirmed their commitment to “reform and openness”. The Chinese govenrment has undertaken a new round of neoliberal “economic reforms” including privatization of the remaining state-owned enterprises and financial liberalization.

Despite growing popular opposition, European capitalist classes were determined to impose fiscal austerity programs on the working classes. In the Middle East, the initial promises of the “Arab Spring” have been replaced by political chaos and social miseries as the region plunged into a complex web of class conflicts, religious fundamentalism, and imperialist intervention.

The economic and social success of Latin American progressive governments has been partially based on the global commodity boom driven by China’s demands for energy and raw materials. Ironically, as the Chinese capitalist economy slows down, global commodity prices have collapsed. Latin American progressive governments are now struggling for their political survival.

It appears that, for the moment, the global ruling elites have brought the system back to life and put the popular challenges against the system under control. However, underneath this apparent stability, a new crisis is approaching.

This book will argue that by the 2020s, economic, social, and ecological contradictions are likely to converge in China, leading to a major crisis for Chinese and global capitalism. Unlike the previous major crises, the coming crisis may not be resolved within the historical framework of capitalism.

Global Capitalism: Crisis and Restructuring

Capitalism is a unique historical system based on the endless accumulation of capital. The modern capitalist world system emerged in Western Europe in the sixteenth century and became the globally dominant system in the nineteenth century. The rise of global capitalism depended upon a set of historical conditions that provided cheap and abundant supply of labor force, energy, and material resources. However, by the early twenty-first century, the various conditions that historically have underpinned the operation of the capitalist world system are beginning to be undermined.

The capitalist world system operates as a “world-economy” with multiple political structures rather than as a “world-empire” with a single dominant political structure (Wallerstein 1979: 5–6). The competition between multiple states compels the “nation-states” to provide favorable political conditions for capital accumulation. But excessive inter-state competition undermines the system’s long-term common interests and threatens the survival of the system. Thus, a state more powerful than all the other states or a hegemonic power is needed to regulate the inter-state competition and promote the “systemic interests” (Arrighi and Silver 1999: 26–31).

Historically, the United Provinces (the Dutch Republic), the United Kingdom, and the United States have been the successive hegemonic powers. US-led global capitalist restructuring in the mid-twentieth century helped to resolve the systemwide major crisis over the period 1914–1945 and paved the way for the unprecedented boom of the global capitalist economy from 1950 to 1973.

The US-led restructuring succeeded in part by accommodating the challenges of the “anti-systemic movements”. These movements represented the interests of the social groups that were created during the previous stages of global capitalist expansion. These included the “social democratic movement” which represented the western working classes, the “national liberation movement” which represented the non-western indigenous elites (the “national bourgeoisies”), and the “communist movement” (Wallerstein 2003).

The modern communist movement originated from the left wing of the social democratic movement in the early twentieth century. But by the mid-twentieth century, it had evolved into a radical variant of the national liberation movement (Wallerstein 2000a). In several peripheral and semi-peripheral states (most importantly in Russia and China) where the old ruling elites were unable to establish the necessary social conditions required for effective capital accumulation, the communist movement succeeded by mobilizing the great majority of the population (the peasants and the proletarianized industrial workers) to create viable nation-states capable of effective competition within the capitalist world system (Chapter 4 of this book will discuss in detail the core, semi-periphery, and periphery as structural positions in the capitalist world system).

During the global economic boom from 1950 to 1973, historical anti-systemic movements were consolidated and new social forces were created. By the late 1960s, the collective demands of the working classes in the core and the semi-periphery started to exceed the capacity of the system to accommodate. The general decline of the profit rate led to a system-wide economic and political crisis.

In response to the crisis, the global capitalist classes organized a counter-offensive. China was one of the key battlegrounds in the global class struggle. By the late 1970s, China’s internal class struggle ended with the decisive victory of the “capitalist roaders in authority within the Communist Party” (a political term used during China’s Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976, referring to the faction of the Chinese Communist Party leadership who were in favor of greater economic and social inequality). China’s reintegration into the global capitalist economy provided the system with the fresh supply of a large cheap labor force. This helped to turn the global balance of power in favor of the capitalist classes who went on to win the global class war in the late twentieth century.

The essence of “neoliberalism” was the dismantling of the global social contract established after 1945 (the “New Deal”) in order to recreate favorable conditions for global capital accumulation. The neoliberal triumph in the 1990s led to the global redistribution of income from the workers to the capitalists. The drastic decline of living standards in many parts of the world reduced the global level of effective demand. Trillions of dollars of speculative capital flowed across national borders, generating financial bubbles followed by devastating crises. The neoliberal global economy was threatened by the tendency towards stagnation and amplified financial instability.

In the late 1990s and the early 2000s, the United States acted as the “consumer of last resort” for the global economy. The US current account deficits helped to absorb surpluses from the rest of the world, allowing China, Japan, and Germany to pursue export-led growth. Within the United States, economic growth was led by debt-financed household consumption. The global economic expansion in the early 2000s rested upon a set of financial imbalances that soon became unsustainable.

The Next Global Economic Crisis?

The Great Recession of 2008–2009 was the deepest economic crisis global capitalism has had since 1945. As the United States, Europe, and Japan struggle to recover from the crisis, global economic momentum shifts from the “developed countries” to the “emerging economies”.

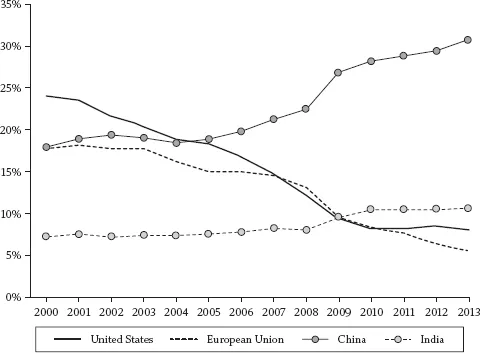

Figure 1.1 compares the relative contribution to global economic growth by the United States, the European Union, China, and India for the period 1990/2000– 2003/2013. For the period 1990–2000, the United States contributed 24 percent of the total world economic growth, the European Union contributed 18 percent, China contributed 18 percent, and India contributed 7 percent. For the decade 2003–2013, China contributed 31 percent of the total world economic growth, India contributed 11 percent, the United States contributed 8 percent, and the European Union contributed only 6 percent.

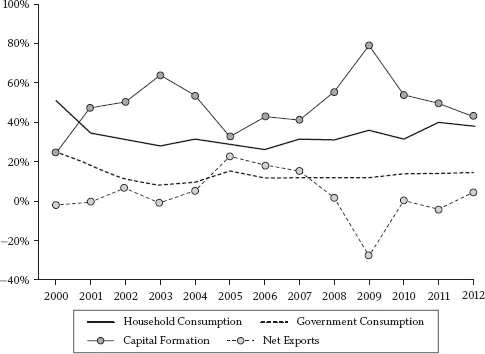

Before 2008, China’s economic growth was driven by investment and net exports. Since then, China’s economic growth has been dominated by investment. Figure 1.2 compares the relative contribution to China’s economic growth by the four components of gross domestic product (GDP): household consumption, government consumption, capital formation (investment), and net exports (exports less imports) for the period 2000–2012.

For the period 2005–2007, investment contributed about 40 percent of China’s economic growth and net exports contributed about 20 percent. In 2009 (at the depth of the global economic crisis), China’s net exports growth turned negative, subtracting 28 percent from China’s economic growth. Fueled by massive fiscal stimulus programs, investment contributed 80 percent of China’s economic growth in 2009.

Figure 1.1 Contribution to Global Economic Growth (1990/2000–2003/2013)

Source: Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in constant 2011 international dollars for the world and individual countries from 1990 to 2013 is from the World Bank (2014). An economy’s contribution to global economic growth is calculated as the ratio of the economy’s cumulative growth of GDP over the cumulative growth of world GDP over a ten-year period.

Figure 1.2 Contribution to China’s Economic Growth (2000–2012)

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China (2013 and earlier years). A macroeconomic component’s contribution to economic growth is calculated as the ratio of the component’s annual change over the nominal GDP’s annual change.

Since then, western capitalist economies have struggled with debt crises and economic stagnation. China’s exports growth has slowed and net exports have made only an insignificant contribution to the overall economic growth. Investment, on the other hand, has been the largest source of China’s economic growth.

The excessively high level of investment is driving down China’s capital productivity, leading to falling profit rates for the capitalists. As a capitalist economy is driven by the pursuit of profit, declining profit rates threaten to undermine capital accumulation. If many capitalists fail to pay back debts as their returns on capital fall below expectations, an accumulation crisis will turn into a financial crisis.

Before 2008, the United States functioned as the main stabilizing force for the global capitalist economy. Since then, China has become the driving engine of global economic growth. If both the United States and China are trapped in economic crisis, what else can prevent the global capitalist economy from falling into a vicious downward spiral?

Class Struggle

In The Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx predicted that the modern proletariat – or the social class of wage workers – would one day become the “grave diggers” of the capitalist system.

Marx’s argument was based on the following reasoning. The growth of capitalist industry tended to destroy handicrafts and small farms, turning peasants and small producers into “proletarians” who did not own the means of production and had to sell their labor power to make a living. As individuals, proletarians were vulnerable to capitalist exploitation. However, modern capitalist production was based on collective labor processes. The workers worked together in capitalist factories and lived together in towns and cities. Their concentration made it relatively easy for the workers to get organized. Capitalist economic development provided improved means of transportation and communication, making it possible for the workers to get organized in entire regions and countries. The growth of workers’ organizations made the working class stronger. Eventually, the entire working class would be organized as a revolutionary political party, overthrowing the capitalist system (Marx and Engels, 1978[1848]).

By the beginning of the twentieth century, there were working class political parties in most European countries. Many of them adopted Marxism as their official political program. Although a European workers’ revolution did not materialize after the First World War, the “specter of communism” was a constant threat to the European capitalist classes throughout the first half of the twentieth century. The threat forced the global capitalist classes to make major concessions after 1945.

The post-1945 “New Deal” included a “capital-labor accord”, a welfare state, and Keynesian macroeconomic policy. The “capital-labor accord” promised that the Western working classes could expect steadily rising real wages in proportion with the growth of labor productivity. In return, the working class would refrain from challenging the capitalist ownership of the means of production (Gordon, Weisskopf, and Bowles 1987). The welfare state provided that the government would guarantee a minimum lifetime income (in the form of pensions and unemployment benefits) and cover a substantial portion of the cost of labor power reproduction (in the form of socialized education and health care). In addition, the government was expected to use Keynesian macroeconomic policy to ensure a reasonably high level of employment.

In effect, the post-1945 “New Deal” allowed the western working classes to receive a portion of the world surplus value in exchange for their political cooperation with the capitalist system. The global capitalist concessions were made possible by the transfer of surplus value from the periphery to the core and the massive consumption of cheap fossil fuels, especially oil.

By the 1960s, strengthened by the long economic boom and welfare state institutions, the western working classes demanded an even bigger share of the world surplus value. The semi-peripheral working classes (in the former Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, and Latin America) also demanded a share of the world surplus value. Squeezed by higher wages, higher taxes (to pay for the welfare state expenditures), and rising energy costs, global capitalism was in deep crisis. The global capitalist classes responded with a counter-offensive. But in the 1970s, the outcome of the global class war was by no means certain.

China’s counter-revolution changed the global balance of power. The “opening-up” of China made it possible for the western industrial capital to be relocated to China, exploiting China’s massive cheap labor force. By the beginning of the twenty-first century, China became the center of global manufacturing exports.

What happened in Europe in the nineteenth century is now taking place in China. Capitalist industrialization and urbanization have brought about fundamental changes to China’s social structure. Proletarianized working class is becoming the majority of the Chinese population. A new generation of Chinese workers is demanding economic, social, and political rights. The Chinese workers’ struggles have grown in size and in militancy. Despite government repression, the workers have been able to win concessions from the capitalists. In recent years, wages have grown more rapidly than labor productivity. Both the capitalist profit share (the share of profit in economic o...