![]()

1

The United Kingdom

INTRODUCTION

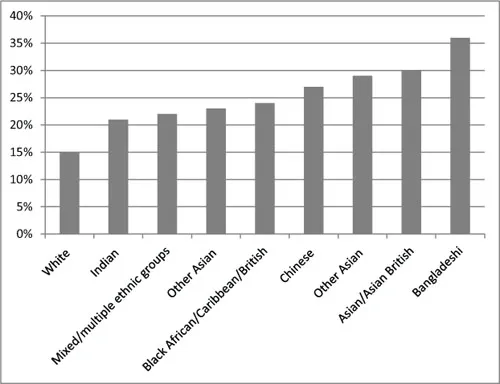

In the Introduction to this book, I referred to the close correlation between poverty and racism, and the way in which they reinforce each other. As Helen Barnard of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation points out, referring to a report on ethnicity by think tank Policy Exchange,1 it ‘does not highlight one of the most important facts about ethnicity in Britain: there is more poverty in every ethnic minority group than among the White British population’2 (see Figure 1.1). The legacy of empire, therefore, still looms large in the United Kingdom. However, this by no means tells the whole story of racism there. In the Introduction, I argued for a wide-ranging definition of racism. Such a definition must include non-colour-coded racism. In many accounts of racism, assumptions are made that it is solely about skin colour. In reality, significant forms of racism in the United Kingdom are not colour-based. In the immediate post-war period of mass migration, white Irish workers were racialized, along with Asian and African-Caribbean migrants. As immigrants’ children entered school, they too were on the receiving end of processes of racialization.3 With the mechanization of farming, many English Gypsies moved from rural areas to cities and towns, encountering hostile reactions from the local population and from the authorities,4 with similar consequences of racialization as their children entered the education system. Given the presence in England of Irish Travellers, anti-Gypsy, Roma and Traveller racism is compounded with anti-Irish racism.

Islamophobia became a major form of racism in Britain after the first Gulf War (1990–91),5 intensifying after 9/11 and 7/7. This form of racism may be termed hybridist,6 in that Muslims may or may not be subject to colour-coded racism and are often marked out not so much by their colour as by their beards and headscarves.7

These various and multifaceted forms of colour-coded, non-colour-coded and hybridist racism were made even more convoluted when in 1993 the Maastricht Treaty created the European Union. The integration of the United Kingdom into Europe and the disintegration of Eastern Europe has witnessed yet another form of racism directed at (predominantly) white Eastern European migrant workers and their families: xeno-racism.8 In addition, in the 1990s ‘asylum seekers’ became racialized as both centre-right and centre-left parties in Europe began to implement laws that criminalized them.9 All these types of racism need to be contextualized alongside ongoing and continuing antisemitism, still a significant form of non-colour-coded racism in the second decade of the twenty-first century, with racialization dating back centuries. There can, of course, be permutations among these various forms of racism.

Figure 1.1 Poverty rates by ethnic group, HBAI (households below average income), June 2013

Source: Gov.UK, ‘Households below average income (HBAI) statistics’, 1 July 2014, www.gov.uk/government/collections/households-below-average-income-hbai–2

In this chapter, I begin by looking at what I call older colour-coded racism from the colonial era up to the present, concentrating on people of Asian, black African, black African Caribbean and Chinese origins. I go on to examine older non-colour-coded racism, focusing on anti-Irish racism, antisemitism and anti-Gypsy Roma and Traveller (GRT) racism, before turning to a consideration of newer forms of racism. Under this heading, I discuss both newer non-colour-coded racism, namely xeno-racism and newer hybridist racism, which can be either colour-coded or non-colour-coded. In this final categorization, I include both Islamophobia (in this section I refer to the decline of state multiculturalism) and anti-asylum-seeker racism.10 Throughout, I relate (changes in) racism to (changes in) the requirements of capitalism, and the ways in which this is mediated by the apparatuses of the state: in particular, the political establishment and the media. I go to make some observations on racism in the run-up to the 2015 general election, before concluding with a discussion of racism in the context of austerity capitalism.

OLDER COLOUR-CODED RACISM: THE COLONIAL ERA AND ITS LEGACY

Empire, Nation and ‘Race’

Racialization is of course historically and geographically specific. Thus, in the British colonial era, when Britain ruled vast territories in Africa, Asia, the Caribbean and elsewhere, implicit in the rhetoric of imperialism was a racialized concept of ‘nation’, whereby the British were ‘destined’ to rule the inferior ‘races’ in the colonies.

Biological racism at the time of the British Empire was considered a science. One example of scientific racism will suffice, here directed at Africans by a president of the Anthropological Society of London, James Hunt:

there is as good a reason for classifying the Negro as a distinct species from the European as there is for making the ass a distinct species from the zebra; and if we take intelligence into consideration in classification, there is far greater difference between the Negro and the Anglo-Saxon than between the gorilla and chimpanzee … the analogies are more numerous between the Negro and apes than between the European and the ape. The Negro is inferior intellectually to the European … the Negro is more humanised when in his natural subordination to the European, than under any other circumstances … the Negro race can only be humanised and civilised by Europeans … European civilisation is not suited to the requirements and character of the Negro.11

The ongoing ferocious and relentless pursuit of expanding capital accumulation in the days of the British Empire in the nineteenth century has to be seen in the context of competition from other countries, and the need to regenerate British capitalism amid fears that sparsely settled British colonies might be overrun by other European ‘races’.

On the affinity between ‘race’ and class in the European mind in general, but prescient of the attitudes of the Victorian ruling class in particular, V. G. Kieran writes:

If there were martial races abroad, there were likewise martial classes at home: every man could be drilled to fight, but only the gentleman by birth could lead and command. In innumerable ways his attitude to his own ‘lower orders’ was identical with that of Europe to the ‘lesser breeds’. Discontented native in the colonies, labour agitator in the mills, were the same serpent in alternate disguises. Much of the talk about the barbarians or darkness of the outside world, which it was Europe’s mission to rout, was a transmuted fear of the masses at home.12

Bernard Semmel has developed Karl Renner’s concept of social imperialism to describe the way in which the ruling class attempted to provide a mass base for imperialism. Social imperialism made the links between nation and empire:

Social-imperialism was designed to draw all classes together in defence of the nation and empire and aimed to prove to the least well-to-do class that its interests were inseparable from those of the nation.13

The ideology of social imperialism, as Semmel points out, was presented to the working class by the Unionist Party in many millions of leaflets and in many thousands of street-corner speeches.14 In addition, there were set up self-professed propaganda organizations, such as the Primrose League, established in 1883. The League was organized on medieval lines: its full members were described as knights and dames and imperial knights, whereas the working class were enrolled as ‘associate members’. By 1891 it was claiming a million members; by 1901 1.5 million, of which 1.4 million were said to be working class.15 Its very effective propaganda exploited each of the imperial highlights of the 1880s and 1890s, such as the death of Gordon at Khartoum and the Boer War. Its leaflets had direct and simple messages, and it dressed up its propaganda in the guise of popular entertainment, often taking the form of ‘tableaux vivants’, magic lantern displays, lectures and exhibitions.16

By the end of the nineteenth century, the ideology of the ‘inferiority’ of Britain’s colonial subjects and the consequent ‘superiority’ of the British ‘race’ was, then, available to all. As far as popular culture in general is concerned, patriotism and Empire were highly marketable products from the late 1800s to 1914. There were a number of reasons for this. First, important social and economic changes had occurred, especially the transformation of Britain into a predominantly urban, industrial nation.17 Basic state education, available after the 1870 Act, and underpinned by imperial themes,18 and technical developments19 facilitated the introduction of cheap popular imperialist fiction.20 Britain’s imperial ‘adventures’ were justified by institutional racism in popular culture: in music halls,21 in juvenile fiction,22 in popular art23 and in the education system. For example, with respect to the educational ideological state apparatus (ISA), textbooks attempted to justify the continuance of ‘the strong arm and brave spirit … of the British Empire’.24 An imperial ‘race’ was needed to defend the nation and the colonies.25 Thus, the African subjects of the colonies were racialized, in school textbooks, as ‘fierce savages’ and ‘brutal and stinking’,26 while freed Caribbean slaves were described as ‘lazy, vicious and incapable of any serious improvement or of work except under compulsion’.27 At the same time, references were made to ‘the barbaric peoples of Asia’,28 and the most frequent impression conveyed about Indians and Afghans was that they were cruel and totally unfit to rule themselves.29 Missionary work was seen as ‘civilizing the natives’. Racism in all its manifestations had become collective ‘common sense’.

John Hobson writes of the importance of ‘hero-worship and sensational glory, adventure and the sporting spirit: current history/falsified in coarse flaring colours, for the direct stimulation of the combative instincts’.30 Springhall states:

that the ‘little wars’ of Empire, which took place in almost every year of Queen Victoria’s reign after 1870, provided the most readily available source for magazine and newspaper editors of romantic adventure and heroism set in an exotic and alien environment.31

Such images, Springhall continues,32 were also apparent in commercial advertising, school textbook illustrations, postcards, cigarette cards, cheap reproductions and other ephemera which appropriated and mediated the work of popular British artists of the time. Scientific biological racism had thus become institutionalized in popular culture in the British Imperial era in many ways.

The Empire and China

While imperialism did not take hold in mainland China as it did in other parts of Asia, Africa and the Caribbean, China was greatly affected by the British Empire, and its political and cultural legacies are still apparent today in the ex-colony of Hong Kong, despite its now being back under control of (the People’s Republic of) China.33 As a result of a high demand in Britain for tea, silk and porcelain, the British bartered Indian opium in exchange for these goods.34

Opium for medicinal purposes was first manufactured in China toward the end of the fifteenth century, and was used to treat dysentery, cholera and other diseases. It was not until the eighteenth century that there were any accounts of opium smoking in China.35 In 1729, concerned at its debilitating effect, the Chinese imperial government forbade the sale of opium mixed with tobacco and closed down opium-smoking houses.36 Selling opium for smoking ‘was classed with robbery and instigation to murder, and punished with banishment or death’.37

But, as Kristianna Tho’mas points out,38 this did not stop the British, who had gradually been taking over the opium trade from their European capitalist rivals, Portugal and Holland. Much of the opium at this time was grown and manufactured in Britain’s Indian Empire. As Marx put it, noting how the employees of the English East India Company exploited the Indians politically and economically, and facilitated drug addiction on the Chinese:

The … Company … obtained, besides the political rule in India, the exclusive monopoly of the tea-trade, as well as of the Chinese trade in general, and of the transport ...