![]()

SECTION 1

Understanding the Crisis

![]()

1

Planet Earth is Wage-led!

A Simultaneous Increase in the Profit Share by 1 Per Cent-point in the Major Developed and Developing Countries Leads to a 0.36 Per Cent Decline in Global GDP

Özlem Onaran

The dramatic decline in the share of wages in GDP in both the developed and developing world during the neoliberal era of the post-1980s has accompanied lower growth rates at the global level as well as in many countries. Mainstream economics continue to guide policy towards further wage moderation along with austerity as one of the major responses to the Great Recession. In our report for the International Labour Office (Onaran and Galanis, 2012), we show the vicious cycle generated by this race to the bottom. The main caveat of this wisdom is to treat wages as a cost item. However, wages have a dual role affecting not just costs but also demand. We work with a post-Keynesian/post-Kaleckian model, which allows this dual role.

A fall in the wage share has both negative and positive effects

We estimate the effect of a change in income distribution on aggregate demand (i.e. on consumption, investment, and net exports) in the G20 countries. Consumption is a function of wage and profit income, and is expected to decrease when the wage share decreases. Investment is estimated as a function of the profit share as well as demand, and a higher profitability is expected to stimulate investment for a given level of aggregate demand. Finally, exports and imports are estimated as functions of relative prices, which in turn are functions of nominal unit labour costs, closely related to the wage share. The total effect of the decrease in the wage share on aggregate demand depends on the relative size of the reactions of consumption, investment and net exports. If the total effect is negative, the demand regime is called wage-led; otherwise the regime is profit-led. Mainstream economic policy assumes that economies are always profit-led, whereas in the post-Keynesian models the relationship between the wage share and demand is an empirical matter, and depends on the structural characteristics of the economy.

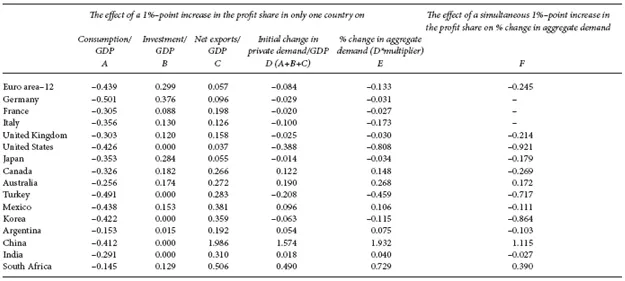

Next, we develop a global model to calculate the effects of a simultaneous decline in wage share. We calculate the responses of each country to changes in domestic income distribution and to trade partners’ wage share. The results are summarised in Table 1.1.

Three important findings emerge. First, domestic private demand (i.e. the sum of consumption and investment in Columns A and B in Table 1.1) is wage-led in all countries, because consumption is much more sensitive to an increase in the profit share than is investment. Second, foreign trade forms only a small part of aggregate demand in large countries, and therefore the positive effects of a decline in the wage share on net exports (Column C) do not suffice to offset the negative effects on domestic demand. Similarly, in the euro area as a whole, the private demand regime is wage-led. Finally, even if there are some countries, which are profit-led, the planet earth as a whole is wage-led. A simultaneous wage cut in a highly integrated global economy leaves most countries with only the negative domestic demand effects, and the global economy contracts. Furthermore some profit-led countries contract when they decrease their wage-share, if a similar strategy is implemented also by their trading partners. Beggar-thy-neighbour policies cancel out the competitiveness advantages in each country and are counter-productive. ILO (2012:60) in the Global Wage Report 2012/13 writes ‘the world economy as a whole is a closed economy. If competitive wage cuts or wage moderation policies are pursued simultaneously in a large number of countries, competitive gains will cancel out and the regressive effect of global wage cuts on consumption could lead to a worldwide depression of aggregate demand.’

At the national level, the US, Japan, the UK, the Euro area, Germany, France, Italy, Turkey and Korea are wage-led. Canada and Australia are the only developed countries that are profit-led; in these small open economies, distribution has a large effect on net exports (see Columns D and E). Argentina, Mexico, China, India, and South Africa are also profit-led.

Table 1 Summary of the effects of a 1%-point increase in the profit share (a decline in the wage share) at the national and global level

Race to the bottom leads to lower global growth

At the global level, the race to the bottom in the wage share, i.e. simultaneous increase in the profit share by 1 per cent-point in the major developed and developing countries, leads to a 0.36 per cent decline in global GDP. The euro area, the UK, and Japan contract by 0.18–0.25 per cent and the US contracts by 0.92 per cent as a result of a simultaneous decline in the wage share (see Column F in Table 1.1). Some profit-led countries, specifically Canada, India, Argentina and Mexico, also contract as a result of this race to the bottom. The expansionary effects of a pro-capital redistribution of income in these countries are reversed when relative competitiveness effects are reduced as all countries implement a similar low wage competition strategy; this consequently leads to a fall in the GDP of the rest of the world. The wage-led economies contract more strongly in the case of a race to the bottom. Australia, South Africa and China are the only three countries that can continue to grow despite a simultaneous decline in the wage share.

The microeconomic rationale of pro-capital redistribution conflicts with the macroeconomic outcomes

First, at the national level in a wage-led economy, a higher profit share leads to lower demand and growth; thus even though a higher profit share at the firm level seems to be beneficial to individual capitalists, at the macroeconomic level a generalised fall in the wage share generates a problem of realisation of profits due to deficient demand. Second, even if increasing profit share seems to be promoting growth at the national level in the profit-led countries, at the global level a simultaneous fall in the wage share leads to global demand deficiency and lower growth.

Policy implications

At the national level, if a country is wage-led, pro-capital redistribution of income is detrimental to growth. There is room for policies to decrease income inequality without hurting the growth potential of the economies.

For the large wage-led economic areas with a high intra-regional trade and low extra-regional trade, like the euro area, macroeconomic and wage policy coordination can improve growth and employment. The wage moderation policy of the euro area is not conducive to growth.

Debt-led consumption, enabled by financial deregulation and housing bubbles seemed to offer a short-term solution to aggregate demand deficiency caused by falling wage share in countries like the US, UK, Spain or Ireland until the crisis. The current account deficits and debt in these countries were matched by an export-led model and current account surpluses of countries like Germany, or Japan, where exports had to compensate for the decline in domestic demand due to the fall in labour’s share. However this model also proved to be unsustainable as it could only co-exist with imbalances in the other European countries – an issue, which is now in the epicentre of the euro crisis.

A global wage-led recovery as a way out of the global recession is economically feasible. Growth and an improvement in equality are consistent. This is true for wage-led and profit-led countries. We present a scenario, where all countries can grow along with an improvement in the wage share, and the global GDP would increase by 3.05 per cent (Onaran and Galanis, 2012).

The austerity policies with further detrimental effects on the wage shares since 2010 will only bring further stagnation. Growth in China and a few developing countries alone cannot be the locomotive of global growth.

A global wage-led recovery can also create space for domestic demand-led and egalitarian growth strategies rather than export orientation based on low wages in the developing countries. Second, even if some important developing countries are profit-led, like China and South Africa, south–south cooperation can create a large economic area, where destructive wage competition policies are avoided.

Rebalancing growth via increasing domestic demand in the major developing countries, in particular China would also be helpful in addressing global imbalances. However, this rebalancing can only take place in an international environment where the developed countries not only leave space for developmentalist policies, support technology transfer, but also create an expansionary global environment.

Given the profit-led structures in some developing countries, the solution requires a step forward by some large developed economies in terms of radically reversing the pro-capital distribution policies.

References

International Labour Organisation (2012) Global Wage Report 2012/13, International Labour Office. Available from www.ilo.org.

Onaran, Ö. and Galanis, G. (2012) ‘Is aggregate demand wage-led or profit-led? National and global effects’, Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 40, International Labour Office. Available from www.ilo.org.

![]()

2

From Financial Crisis to Stagnation: The Destruction of Shared Prosperity and the Role of Economics

Thomas I. Palley

Marshall McLuhan, the famed philosopher of media, wrote: ‘We shape our tools and they in turn shape us.’ His insight also applies to the economy which is shaped significantly by economic policy derived from economic ideas. The critical role of economic policy and ideas is central to understanding the continuing global economic crisis which is the product of flawed policies derived from flawed ideas.

Competing perspectives on the crisis

Broadly speaking, there exists three different perspectives on the crisis. Perspective #1 is the hardcore neoliberal position, which can be labelled the ‘government failure hypothesis’. In the US it is identified with the Republican Party and the Chicago school of economics. Perspective #2 is the softcore neoliberal position, which can be labelled the ‘market failure hypothesis’. It is identified with the Obama administration, half of the Democratic Party, and the MIT economics departments. In Europe it is identified with Third Way politics. Perspective #3 is the progressive position which can be labelled the ‘destruction of shared prosperity hypothesis’. It is identified with the other half of the Democratic Party and the labour movement, but it has no standing within major economics departments owing to their suppression of alternatives to orthodox theory.

The government failure argument holds that the crisis is rooted in the US housing bubble and bust which was due to failure of monetary policy and government intervention in the housing market. With regard to monetary policy, the Federal Reserve pushed interest rates too low for too long in the prior recession. With regard to the housing market, government intervention drove up house prices by encouraging homeownership beyond peoples’ means. The hardcore perspective therefore characterises the crisis as essentially a US phenomenon.

The softcore neoliberal market failure argument holds that the crisis is due to inadequate financial regulation. First, regulators allowed excessive risk-taking by banks. Second, regulators allowed perverse incentive pay structures within banks that encouraged management to engage in ‘loan pushing’ rather than ‘good lending’. Third, regulators pushed both deregulation and self-regulation too far. Together, these failures contributed to financial misallocation, including misallocation of foreign saving provided through the trade deficit. The softcore perspective is therefore more global but it views the crisis as essentially a financial phenomenon.

The progressive ‘destruction of shared prosperity’ argument holds if the crisis is rooted in the neoliberal economic paradigm that has guided economic policy for the past 30 years. Although the US is the epicentre of the crisis, all countries are implicated as they all adopted the paradigm. That paradigm infected finance via inadequate regulation and via faulty incentive pay arrangements, but financial market regulatory failure was just one element.

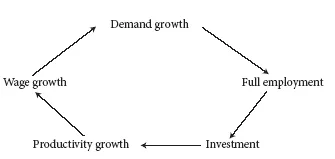

The neoliberal economic paradigm was adopted in the late 1970s and early 1980s. For the period 1945–75 the US economy was characterised by a ‘virtuous circle’ Keynesian model built on full employment and wage growth tied to productivity growth. The model is illustrated in Figure 2.1. Productivity growth drove wage growth, which in turn fuelled demand growth and created full employment. That provided an incentive for investment, which drove further productivity growth and supported higher wages. This model held in the US and, subject to local modifications, it also held throughout the global economy – in Western Europe, Canada, Japan, Mexico, Brazil and Argentina.

Figure 2.1 The 1945–75 virtuous circle Keynesian growth model

After 1980 the virtuous circle Keynesian model was replaced by a neoliberal growth model that severed the link between wages and productivity growth and created a new economic dynamic. Before 1980, wages were the engine of US demand growth. After 1980, debt and asset price inflation became the engine.

The new model is rooted in neoliberal economics and can be described as a neoliberal policy box that fences workers in and pressures them from all sides. It is illustrated in Figure 2.2. Corporate globalisation put workers in international competition via global production networks supported by free trade agreements and capital mobility. The ‘small’ government agenda attacked the legitimacy of government and push...