![]()

1

Sleepwalking City

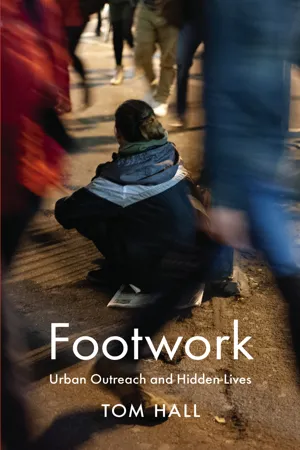

This book is about the city. More than that, or more particularly, it is about city streets and the ways in which those who might come to depend on them are seen by others passing by; not only seen, but sometimes seen to and looked after. This makes it a book about people and what they are prepared to see and do, and the moves they make – again, on the city streets.

The idea that being in the city might be a matter of moves made, suggests a game: turns taken and missed, stratagems and tactics, tricks, forfeits; winners and losers. The comparison would be frivolous were games not a near universal human pastime. Joseph Rykwert takes the dice-and-board game as a guiding analogy in the first few pages of his erudite study The Seduction of Place: The History and Future of the City. The point he seeks to make is that cities are not simply given to us in ways we cannot hope to work with(in) and negotiate:

It seemed to me then – as it still does now … that the city did not grow, as the economists taught, by quasi-natural laws, but was a willed artifact, a human construct in which many conscious and unconscious factors played their part … The principal document and witness to this process was the physical fabric of the city. (2002: 4–5)

We are all of us, Rykwert continues, ‘agents as well as patients in the matter of our cities’ (2002: 5). Our agency is exercised as improvisation on the rule, after each throw of the dice; we have choices to make, about the sorts of city in which we want to live. The choices Rykwert has in mind are those that have shaped urban planning over the last few hundred years, but the same agency is there all the way down to ground level and can be exercised in the course of something as ordinary as a short walk.1 There are the rules and conventions with which the material city confronts us – this street, that subway, a bridge, a wall, a doorway – and then there is what we choose to make of these, how we choose to move and where, what we are prepared to do in order then to see what happens next. Footwork is a study of just these sorts of moves, rules and gambits, exercised on the city street.

Put concretely, Footwork describes the operating practices of a team of ‘outreach’ workers, charged to look after people found in difficulties on the streets of only one city: Cardiff. Just about all the action in the book comes from Cardiff because that is the city in which I live; I came to Cardiff in 1997 (I was born and grew up in Manchester). This makes it a very local account, and as such it stands for itself. The team I am interested in was established around about the same time that I arrived in Cardiff and continues its work today, so we are inadvertently paired in that way; but I am also close to the team as a result of having purposely shared its work – the various moves that outreach requires – over a number of years, as observer and participant. Which makes this book an ethnography of a certain sort of street work: outreach.

The book has a wider horizon too and I give notice of that in this opening chapter and a good part of the next. To write about a city’s streets and what gets done there is to open up the possibility at least that what you have to say might bear on city streets elsewhere and what happens there or might do, and it is absolutely the case that outreach work of something like the sort I will report on here happens in a good few cities around the world. It happens in Manchester, certainly; I’ve seen it in New York and spent time there with the people whose job it is to do it. But I am reporting only from Cardiff, and as such the book supplies no evidence; it does not stand as proof of something else. What it does supply, if not evidence, is an example. As anthropologists Lars Højer and Andreas Bandak have it, examples are attentive to ‘unruly details’ and ‘suggestive as much as descriptive’; ‘evidence “makes evident” … and can be gathered (the many become one), whereas exemplification multiplies, makes connections and evokes (the one becomes many)’ (2015: 8, 12). We shall see.

Coming round

Cities grow and change, and sometimes die – or are said to. People do too. People also sleep, which is something the modern city does rather less of, if at all. Almost any city in the twenty-first century might claim to be a city that never sleeps, and most would be pleased to do so. For some commentators, these processes of growth and change and death are linked: urban development bereaves us even as it delivers something new. A brand-new building towers where an older one once stood, and mixed in with the thrill of transformation and renewal is the uneasy feeling that a part of the city has been lost.

Some have put it more strongly than that. Louis Chevalier for one, whose angry and partisan account, The Assassination of Paris, records a city done to death by indifferent technocrats and greedy developers: skyscrapers, automobiles, chewing gum, ‘buildings cheaply thrown up around a supermarket in the middle of a parking lot … a few stunted trees’ (1994: 71; originally 1977); a restless, predatory modernization. Sleep has also had a part to play:

Will Paris always be Paris …? Without doubt. But these towers suddenly thrusting up on the horizon, all at once, in a few months … like those monsters in Japanese films who rouse themselves from a millennial sleep, get up on their haunches, and destroy cities … The towers were there … everywhere, flaunting their ugly silhouettes, cut off at the top, grotesquely inclined this way and that, like King Kong … We are only at the beginning, just waking up, and I had, as at any awakening, only a confused, obscure memory of a long and extraordinary illusion. (1994: 3)

Like the monsters recently awakened, Chevalier has been sleeping – has been blind; his eyes closed even when walking the streets:

Perception is itself a matter of habit. Images from the past obscure the eye … At first we do not see, or we see without registering the image. Then, when it is no longer possible not to see, we arrange things, first instinctively then deliberately, to avoid seeing them as much as possible. We take complicated routes to avoid the monsters … one can always choose one’s subway stop, take another street and even, while in enemy territory, close an eye, open an umbrella … The more present-day Paris annoyed me, the more I turned to the past, played hide-and-seek. (1994: 4)

I will have more to say about hide-and-seek in the city. Chevalier talks of turning to the past, but there are other ways in which to look away, and there is in any case something wholly contemporary about acts of urban unseeing. We all close our eyes to the city some of the time, choosing to ignore a lot of what takes place around us. A sort of blindness might even be necessary to city life, thinning out the massive sensory input available to us at any one time, the artefactual and architectural cacophony of the streets. Urban environments exceed our ability to encompass them, even in a frozen moment – never mind the swinging perspectives brought on by movement, never mind the upheavals of configuration brought on by construction and demolition (Barber, 1995: 29). And in this sense we have no choice at all; the city is too much, and we must shut it out or at any rate manage and prioritise our encounter with it – closing an eye, picking our route, opening an umbrella.

Nor is this just a matter of ourselves and the built environment. We are not alone in the city: there are countless others there too. Some of the ways in which we see and seek out, and also hide from these others, or fail to see them, in the midst of a changing cityscape, is the subject of this book.

Eyes wide shut

The idea of the city as a hard place is an old saw: hard in itself, as a physical site – built to last, like the third little piggy’s house – but hard also in the sense that the people living there are said to be distant and unfeeling, with not much time for others they do not already know; they look past you in the street, right through you. To be hard in this way is to belong to the city. The implied contrast is that between an urban way of life and personality and some other existence where something more like kindness and community prevail, most likely rural. But it is not all bad news for the city. If city dwellers are unfriendly, they are also said to be savvy and sharp, go-getting, sophisticated too – although this word can bite back. This distinction between city life and country living reaches back a long way (see Williams, 1973); it is of course ideological and has been variously put to work and imagined – but it is not wholly imaginary, not simply false. As a contrastive device, it has played a particular role in sociological analyses of the modern industrial city and its progeny. It was central to the work of the Chicago school of urban sociology, whose investigations of city life are generally recognised as having established modern urban studies (Hannerz, 1980: 20). For the Chicago sociologists the modern city was ‘remaking human nature’, establishing new types of personality, modes of thought and a ‘city mentality … clearly differentiated from the rural mind’; the difference was ‘not merely one of degree, but of kind’ (Wirth, 1984: 219–222; originally 1925). Cities were different sorts of places; city dwellers were different sorts of people.

Central to this analysis was the idea that city life was a matter of living among strangers, and a matter of getting used to this. Strangers in the city were not, as elsewhere, occasional figures not from round here and most likely gone tomorrow. Strangers were locals, the very inhabitants with whom life was going to have to be made from one day to the next; they belonged in the city no less than you did. Strangers were the city, and urbanism as a way of life meant managing that extraordinary circumstance somehow. Along something like the same lines, Nigel Thrift has recently argued that the jar and scrape of everyday encounters with others we do not know makes the city essentially anti-social: misanthropy, he suggests, is a ‘natural condition of cities, one which cannot be avoided and will not go away’ (2005: 140). He describes cities today as threaded through with aversion and ill-will, even hatred: ‘cities are full of impulses which are hostile and murderous and which cross the minds and bodies of even the most pacific and well-balanced citizenry’ (2005: 140). Is the city really as hard as all that? Here is Jonathan Raban on the well-balanced citizenry of 1970s London:

Coming out of the London Underground at Oxford Circus one afternoon, I saw a man go berserk in the crowd on the stairs. ‘You fucking … fucking bastards!’ he shouted, and his words rolled round and round the lavatorial porcelain tube as we ploughed through. He was in a neat city suit, with a neat city paper neatly folded in a pink hand … What was surprising was that nobody showed surprise: a slight speeding-up in the pace of the crowd, a turned head or two, a quick grimace, but that was all … Who feels love for his fellow-man at rush hour? Not me. I suspect the best insurance against urban violence is the fact that most of us shrink from contact with strangers. (1988: 12; originally 1974)

A moment of urban frenzy; a decidedly odd thing for a man in a neat city suit to do. And yet the incident is nothing really, not at all newsworthy, just one of those things that happen sometimes in the city, more often than we care to notice.2

Most of us are familiar with the sudden flare-up of urban ill-temper, even rage. The impulse is always there, as a possibility, and we are prepared for it. Just another one of those things. Only last week I saw a man assaulted outside a pub, across the road from where I was sitting in my car. It was an explosive escalation of what seemed to have been a petty row, and was all over in seconds. He got up from the ground, his shirt-front spattered with blood, and retreated inside, backing through the pub door, his hands raised. His attacker stayed outside and stalked up and down the pavement, gesturing angrily but with diminishing conviction, running himself down like a clockwork toy. A third man leaning against the wall of the pub watched the whole thing over the top of his pint glass without once moving or giving any sign that he had actually seen anything. I waited for the lights to turn green, and drove on. This was something more than the jar and scrape of city life, but nothing traumatic in any sense that could be said to have widened beyond those directly involved. No one witness to the assault seemed to think it worth doing anything much about, myself included. No one tried to get involved, and no one was visibly upset other than the two protagonists. I did flinch a little, inwardly, at the time, but that was about it. I suppose others – the third man, leaning on the wall – may have done the same.

To flinch is to shy or turn away, also to shrink under pain. The idea that another’s pain might be ours as well, or that our sharing of it, imaginatively, might be the way through to fellow-feeling, can be found in Adam Smith’s moral philosophy. Smith argues that it is human nature to feel pity or compassion for the misery of others; sympathy: ‘[t]he greatest ruffian, the most hardened violator of the laws of society, is not altogether without it’ (2002: 11; originally 1759). Yet if we are not without pity this is still some way off from routinely taking a hand in the lives of others – parking the car and getting out and crossing the road to check that someone, a stranger, is going to be OK. Smith’s account starts with what we might see, and how that might make us feel: we see a blow fall and we imagine how it might feel to have been hit – perhaps we flinch. But if we (already) shrink from contact with strangers, as Raban has it, what does it matter if we also flinch when we see a stranger hurt? What we see of their injury leads nowhere.3 Is seeing enough? Not enough for Richard Sennett, who writes:

In the course of the development of modern, urban individualism, the individual fell silent in the city. The street, the café, the department store, the railroad, bus and underground became places of the gaze rather than scenes of discourse. When verbal connections between strangers in the modern city are difficult to sustain, the impulses of sympathy which individuals may feel in the city looking at the scene around them become in turn momentary – a second of response looking at snapshots of life. (2002: 358)

To gaze is to stare, to look vacantly but at the same time fixedly; snapshots are images taken (out) of passing life. But it does not follow that this is how we only ever see, the eye like a camera. There are other ways of looking, not so fixed or photographic. To see in a way that engages others – strangers, and their needs – and the world around us is not so much to gaze at as to enquire and question, to look (out) for and look after. A discursive attention, perhaps. In large part, and in the detail certainly, that is what this book is about. I intend to provide a record of what looking out for others on the city street looks like – how it appeared to me at least, having shared time with a group of people dedicated to just that undertaking.

Strangers, streets and walls

The general problem as some have framed it is that cities bring people together in large numbers but not as one big (happy) family. The effect can be claustrophobic. Living with strangers makes us edgy, but also indifferent; we shrink from contact, and all the while ‘the run of daily life … [feeds] back into the city’s fabric as an undertow of spite’ (Thrift, 2005: 141). Plaited together, a determined suspicion and unconcern, each of these a refusal properly to see another person, supply a necessary technique for managing all that proximity – the push and shove of all those other lives pressed close around us. The classic statement of this urban condition belongs to the German sociologist Georg Simmel, who suggests that ‘antipathy which is the latent adumbration of actual antagonism … brings about the sort of distanciation and deflection without which this type of life could not be carried on at all’ (1971: 331; originally 1903).4 Ill-disposed to others, disinclined to make them our concern, we gaze blankly, or look away. We do not see them and are closed, ourselves, in turn. We may even pick our routes, like Chevalier, arranging things – instinctively, deliberately – so as to avoid encounters with those to whom our sympathy least comfortably extends. Should we come across any one such by chance, we may close an eye – so as not to flinch.

The city street is the archetypal location for such unconcern: the street is the place where strangers walk on by. And then what? Where do they walk on to, these strangers? Off the edge of the page presumably, because ‘the street’ as such is an abstraction, is no real street at all; no one ever walked there, or sat importuning passers-by. Actually existing streets, on the other hand, are somewhere in particular. More than that, they are physical settings – as Rykwert insists. The materiality of real streets, their structure and composition, matters for any human encounter we might have on them, be that encounter kind or unkind. Walking on by the needs of others requires a reasonably firm and dependable surface on which to do so. It cannot happen in mid-air. It can go badly wrong in a muddy field. High-quality granite paving on a laying course of minimum compressive strength 30MPa, well maintained and swept clean – all this makes pedestrian indifference that little bit easier, that little bit more smooth.5 Putting the needs of others behind us is not just a figure of speech: it can be brought off materially, with devastating effect, simply by turning the corner of a building. My point is that the only streets we know are real ones, and real streets are not only physically somewhere, a fragment of geography, but also materially constituted and as such participant in what we might do there. The relationship between the two, between the city street and what we might see and do there, is one of imbrication (Katznelson, 1992: 7).

Given which, if city life is in some ways unseeing we should expect the built environment to confirm this. And in ...