![]()

1

First Encounters with Post-War America and American Culture: the 1940s

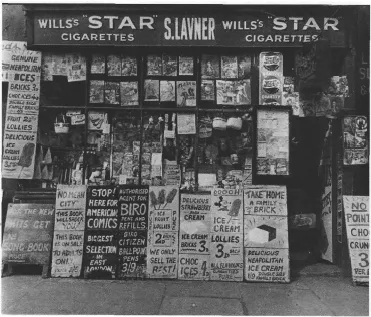

Many British towns and cities during the late 1940s and early 1950s were smoke-blackened places punctuated by areas of devastation due to wartime bombing raids. Especially drab were the working-class, innercity districts consisting of ranks of similar terraces made up of two-storey houses with no front gardens and outside toilets at the back. Often, the only splashes of colour and visual excitement in such areas were the newsagents selling daily papers, magazines and comics, cigarettes and tobacco, ice cream, soft drinks and sweets.

1. Nigel Henderson, Shop Front, East London, c. 1949–52.

Gelatin silver print, 20.3 × 25.4 cm. Estate of the artist. Photo: reproduced courtesy of Janet Henderson.

Nigel Henderson (1917–84), an amateur cameraman of upper-class origins, photographed one such shop – located in Hackney, a poor district in the East End of London – some time between 1949 and 1952. This photograph is a vivid reminder of the penetration of American mass culture into British, proletarian life: the top of the window is full of American crime, detective, pin-up and film magazines while on the pavement below stands a hand-painted board which announces ‘Stop! here for American comics, biggest selection in East London’; a second sign for ice cream lollies is accompanied by a crude depiction of Mickey Mouse’s head; a third displays several Pepsi-Cola bottle tops.

The newsagent’s window is so replete with imagery, products and lettering that one cannot see the shop’s interior. Unwittingly, the shopkeeper had produced a huge collage – similar to the pinboards crowded with images that certain British artists were so fond of generating at the time – in which American and British signs vie for the attention of passers-by. Such newsagents were a familiar sight to the people who were later to be labelled ‘Pop artists’.

Another place where American mass culture was available to working- and middle-class Britons was, of course, the cinema. Before the spread of television in the 1950s caused a decline in cinema attendance, 30 million Britons used to visit 4,500 cinemas (some people went two or three times a week) to view the two feature films shown per programme, plus trailers and Pathe News, and to listen to organ playing during the interval. Cinemas were far more numerous in the 1940s than they are today. Despite a quota system designed to protect the indigenous film industry from being overwhelmed or even destroyed by Hollywood, most of the films screened were American in origin and so certain visions of the American way of life were conveyed to British viewers, most of whom had no way of checking their veracity.

The interest which many British artists were to take in American culture, as Robert Kudielka has observed, ‘was not based on personal experience’ because ‘very few artists … had actually been to the United States. America was a fantasy of mass media via mass media.1 Even before the Second World War – in 1927 – an editorial in the Daily Express had noted:

The bulk of picture goers are Americanised to an extent that makes them regard the British film as a foreign film. They talk America, think America, dream America; we have several million people, mostly women, who, to all intents and purposes, are temporary American citizens.2

Via the contents of American movies a British child would learn far more about the history of the Wild West, the behaviour of private detectives, the police and criminal gangs in the major cities than they would about, say, the history of Europe. The effect of films on the feelings and imaginations of children is incalculable. Michael Sandle (b. 1936), the British sculptor, has acknowledged how the private fantasies and fears that followed watching Hollywood movies as a child fuelled the imagination that inspired the sculpture he made as an adult.3

American vernacular or mass culture was thus much more available to the British than either American or European modern art. Access to the latter usually depended upon an art school education. It also helped to live in London and to be a member of the Institute of Contemporary Arts: some provincial towns had no art galleries at all. At that time, books, magazines and catalogues about the work of living artists were few and far between. And to see what little existed one needed access to an art school library or specialist London bookshops such as Tiranti and Zwemmer.

One European city where new American art could be viewed in the late 1940s was Venice. This was because of the Biennale exhibitions held there and the presence of the American collector, Peggy Guggenheim. She had bought a Palazzo on the Grand Canal and turned it into a museum. As we shall discover, a number of British architects, painters and critics first encountered Abstract Expressionist canvases in Venice.

As mentioned in the Introduction, during the late 1940s a number of British artists travelled to Paris because they assumed it would resume its pre-1939 position as the world’s art capital and that the School of Paris – a galaxy of foreign and French artists: Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Brancusi, Giacometti, et al – would continue to be the cutting edge of artistic innovation. However, once it became clear that America was now the dominant world power and that in Abstract Expressionism it had developed an art movement comparable in ambition and quality to any previous European movement, it dawned on European artists and critics that New York had supplanted Paris as the world’s art capital. To some degree the shift of power across the Atlantic occurred before and during the Second World War when so many artists, especially the Surrealists, fled to America. Clement Greenberg (1909–94), an American critic who was to become extremely influential in the 1950s and 1960s, was later to argue that New York did not become the world’s art capital by rejecting Paris but by assimilating its achievements and then transcending them.

There is an amusing painting by the American artist Mark Tansey (b. 1949) which records the transfer of power. Entitled Triumph of the New York School (1984), it depicts members of the two schools dressed in military uniforms assembled for a surrender ceremony. André Breton, the ‘Pope’ of Surrealism, signs the surrender document for the School of Paris in front of Greenberg, the representative of the victorious New York School.

Even in Paris during the late 1940s it was not possible to escape the presence of America because there were ex-GIs and American artists living there. Eduardo Paolozzi (b. 1924), a Scottish-born sculptor, collagist, film-maker and printmaker of Italian immigrant parents, was one of the British artists who went to Paris – in 1947 – and remained for two years. William Gear and William Turnbull, two other Scottish artists, were also in Paris at roughly the same time. Gear’s abstractions were indebted to the School of Paris but his wife Charlotte was an American and it was thanks to her that a selection of his gouaches were shown at the Betty Parsons Gallery, New York in the autumn of 1949. At the time, Parsons was Jackson Pollock’s dealer.

Paolozzi had grown up in Leith which was then a rough district of Edinburgh. His parents ran ice cream and sweet shops so his social circumstances were of working or lower middle class. Naturally he was exposed to mass cultural influences: he drew footballers, aeroplanes and film stars, copied and collected cigarette cards, and enjoyed American Western and gangster movies screened in local cinemas. He also read comics and pulp magazines full of science fiction stories and tales of air battles. His propensity to collect mass culture material and his fascination with the conjunction of fantasy and machines and technology can therefore be dated to his childhood. The adult Paolozzi was to write:

It is conceivable that in 1958 a higher order of imagination exists in a SF pulp produced on the outskirts of LA than in the little magazines of today. Also, it might be possible that sensations of a difficult-to-describe nature be expended at the showing of a low-budget horror film. Does the modern artist consider this?4

What was valued by the staff in British art schools during the 1940s were the fine arts, the masterpieces of European ‘high’ culture and subjects like the nude. ‘Low’ or mass culture was despised, and students were expected to abandon or suppress any enthusiasm they might have had for it. At that time it was not envisaged that such material might become the content of fine art. Paolozzi – who attended art schools in Edinburgh, London and Oxford (1943–47) – was only one of many British art students who experienced this clash of cultures and tastes. The more adventurous students also tended to identify with modern rather than historic art and this was another bone of contention with tutors because many of them were suspicious of all artistic developments since Post-Impressionism.

In Paris Paolozzi became acquainted with Arp, Brancusi, Dubuffet, Giacometti, Léger and Tzara. He learnt about Dada and Surrealism, in particular the work of Duchamp and Ernst. But while he familiarised himself with modern art, he also made crude collages in scrapbooks from issues of American magazines he was given by some of the wives of ex-GIs whom he met. On their discharge from the armed forces, GIs were given grants to study equalling the number of years that they had served. There were also a number of American artists staying for short or long periods in Paris.

At the time Paolozzi’s collages were not intended as works of art in their own right, but simply as reference and inspiration sources. In the 1970s Paolozzi explained that his attitude to the raw material had been ‘ironic’ and ‘rather surrealist’.5 When Paolozzi showed them to others, their reaction was generally one of amusement. Nevertheless, in retrospect, a plausible claim can be made for Paolozzi being the founder, or at least a key precursor, of Pop art.

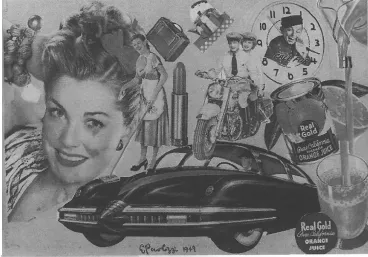

Let us consider the contents of some of Paolozzi’s early collages: I was a Rich Man’s Plaything (1947) consists of the cover of the magazine Intimate Confessions with a smiling semi-naked female on the front, to which has been added the exclamation ‘Pop!’ emerging from a hand-held gun, a slice of cherry pie and the emblem ‘Real Gold’ derived from the label on a tin of Californian fruit juice. Below is a cigarette card illustrating an American bomber with the slogan ‘Keep ‘Em Flying!’, plus the image of a Coca-Cola bottle and a circular advertisement stating ‘Serve Coca-Cola at Home’. Thus, in this loose assembly of images we find the themes of sex, gun culture, military power and junk food and drink. It is left to the viewer to connect them but they certainly serve as an array of the common stereotypes Europeans had of the American way of life.

Another collage, Meet the People (1948), features the head of the film and television star Lucille Ball, the Disney cartoon character Minnie Mouse, a tin of tuna fish, a overhead shot of a fizzy drink and a sumptuous plate of fruit; all superimposed on a colourful, abstract, wavy pattern. A third collage – Sack-O-Sauce, (1948) – represents the collision of European modern art and American mass culture: the ground upon which the cut-out collage elements – which include Mickey Mouse – are pasted is a reproduction of a Miró painting extracted from a copy of Verve that Paolozzi had been given in 1947.

2. Eduardo Paolozzi, Real Gold, 1949.

Collage on paper from the Bunk series, 28 × 40.6 cm. London: artist’s collection. © Eduardo Paolozzi 1998. All rights reserved DACS.

Other collages are dense compilations of images depicting new American cars, motorcycles, roast meat, tinned spam, cameras, kettles, radios, lipstick, housewives in lavishly appointed kitchens, atomic technology, science fiction and striptease scenes. Paolozzi makes no attempt to provide a critique of these images or any explanation as to how and why Americans came to enjoy such material wealth, he simply gathers and presents them. His aim had been ‘to find a kind of connection between those found images and one’s actual experience, to make them into an icon, or a totem, that added up as different types of symbol’.6

When Paolozzi returned to live in London in 1949 he bought reduced-price copies of Colliers and The Saturday Evening Post from newsagents on the Charing Cross Road. The abundance depicted in the advertising pictures they contained was in stark contrast to his own straightened circumstances. Later Paolozzi explained that, for him and his friends:

The American magazine represented a catalogue of an exotic society, bountiful and generous, where the event of selling tinned pears was transformed into multicoloured dreams, where sensuality and virility combined to form, in our view, an art form more subtle and fulfilling than the orthodox choice of either the Tate Gallery or the Royal Academy.7

It signified, therefore, an ‘alternative’ to ‘official’ British culture. Robert Kudielka was later to argue that the American dream, as perceived in Britain via the mass media, ‘made it possible to name what seemed to be wrong with English culture: insular complacency, carefully cultivated amateurism, indulgence in private allusions, and the inclination towards pastoral romanticism.’8 ‘Pastoral romanticism’ was a reference to Neo-Romanticism, the art movement fashionable in Britain during the 1940s. Isolated from Paris and the continent of Europe because of the Second World War, many British artists had resorted to national, landscape and visionary traditions associated with such figures as Samuel Palmer and William Blake. Paolozzi, in contrast, sought inspiration from modern art, the urban environment, mass media and technology.

Once in London again Paolozzi, along with some of his close friends, joined the newly founded Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) and during the 1950s they contributed to the debates and exhibitions that took place there.

The ICA, Sir Herbert Read and his American Trips

The ICA, an important British cultural organisation, was established in the late 1940s by a group of people which included the critic Herbert Read, the patron Roland Penrose, the publisher Peter Gregory and the wealthy collector of modern art and financial backer of Horizon magazine Peter Watson. Their aim was to provide London with a centre for the promotion of modern and contemporary, avant-garde art. The ICA’s first home was at 17 Dover Street – a gallery was opened there in December 1950. Later, in 1967, it transferred to more spacious premises in Nash House, The Mall.

Since the ICA was (and remains) a private organisation, its income was precarious and derived from a variety of sources: membership fees, grants from the Arts Council, entrance charges, sponsorship from ...