![]()

1. Le monde est trop plein

On 28 November 2008, the celebrated French intellectual Claude Lévi-Strauss, the founder of structuralism, celebrated his hundredth birthday. He had been one of the most important anthropological theorists of the twentieth century, and, although he had ceased publishing years ago, his mind had not yet given in. But his time was nearly over, and he knew it. The book many consider his most important had been published almost 60 years earlier. When Les Structures élémentaires de la parenté (The Elementary Structures of Kinship, Lévi-Strauss 1969 [1949]) appeared, it transformed anthropological thinking about kinship by shifting the focus of the field and reconceptualising this most universal of all social modes of being. To Lévi-Strauss, the most significant fact about kinship was not descent from a common ancestor, but rather the alliances between groups created by marriage.

On his birthday, Lévi-Strauss received a visit from President Nicolas Sarkozy, since France remains a country where politicians can still increase their symbolic capital by socialising with intellectuals. During the brief visit, the ageing anthropologist remarked that he scarcely considered himself among the living any more. By saying so, he did not merely refer to his advanced age and weakened capacities, but also to the fact that the world to which he had devoted his life’s work was by now all but gone. The small, stateless peoples who had featured in most of his world had by now been incorporated, with or against their will, into states, markets and monetary systems of production and exchange.

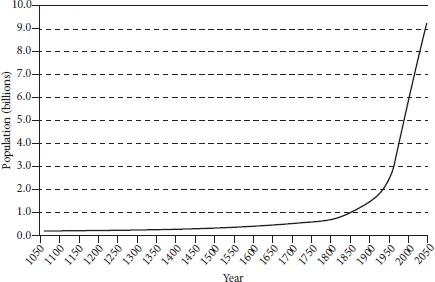

During his brief conversation with the president, Lévi-Strauss also remarked that the world was too full: Le monde est trop plein. By this he clearly referred to the fact that the world was filled by people, their projects and the material products of their activities. The world was overheated. There were by now 7 billion of us compared to 2 billion at the time of the great French anthropologist’s birth, and quite a few of them seemed to be busy shopping, posting updates on Facebook, migrating, working in mines and factories, learning the ropes of political mobilisation or acquiring the rudiments of English.

Lévi-Strauss had bemoaned the disenchantment of the world since the beginning of his career. Already in his travel memoir Tristes Tropiques, published in 1955, he complained that:

Figure 1.1World population growth since 1050

Source: Puiu (2015).

[n]ow that the Polynesian islands have been smothered in concrete and turned into aircraft carriers solidly anchored in the southern seas, when the whole of Asia is beginning to look like a dingy suburb, when shanty towns are spreading across Africa, when civil and military aircraft blight the primaeval innocence of the American or Melanesian forests even before destroying their virginity, what else can the so-called escapism of travelling do than confront us with the more unfortunate aspects of our history? (Lévi-Strauss 1961 [1955]: 43)

– adding, famously, with reference to the culturally hybrid but undeniably modern people of the cities in the New World, that they had taken the journey directly from barbarism to decadence without passing through civilisation. The yearning for a lost world is evident, but anthropologists have been nostalgic far longer than this. Ironically, the very book which would change the course of modern European social anthropology more than any other, conveyed pretty much the same message of loss and nostalgia. Bronislaw Malinowski’s Argonauts of the Western Pacific, published just after the First World War, begins with the following prophetic words:

Ethnology is in the sadly ludicrous, not to say tragic, position, that at the very moment when it begins to put its workshop in order, to forge its proper tools, to start ready for work on its appointed task, the material of its study melts away with hopeless rapidity. Just now, when the methods and aims of scientific field ethnology have taken shape, when men [sic] fully trained for the work have begun to travel into savage countries and study their inhabitants – these die away under our very eyes. (1984 [1922]: xv)

Disenchantment and disillusion resulting from the presumed loss of radical cultural difference has, in a word, been a theme in anthropology for a hundred years. It is not the only one, and it has often been criticised, but the Romantic quest for authenticity still hovers over anthropology as a spectre refusing to go away. Clifford Geertz and Marshall Sahlins, the last major standard-bearers of classic cultural relativism, each wrote an essay in the late twentieth century where they essentially concluded that the party was over. In ‘Goodbye to tristes tropes’, Sahlins quotes a man from the New Guinea Highlands who explains to the anthropologist what kastom (custom) is: ‘If we did not have kastom, we would be just like the white man’ (Sahlins 1994: 378). Geertz, for his part, describes a global situation where ‘cultural difference will doubtless remain – the French will never eat salted butter. But the good old days of widow burning and cannibalism are gone forever’ (Geertz 1986: 105).

It is a witty statement, but it is nonetheless possible to draw the exact opposite conclusion. Regardless of the moral position you take, faced with the spread – incomplete and patchy, but consequential and important – of modernity, it is necessary to acknowledge, once and for all, that mixing, accelerated change, connectedness and the uneven spread of modernity is the air that we breathe in the present world. Moreover, we may argue that precisely because the world is trop plein, full of interconnected people and their projects, it is an exciting place to study right now. People are aware of each other in ways difficult to imagine only a century ago; they develop some kind of global consciousness and often some kind of global conscience virtually everywhere. Yet their global outlooks remain firmly anchored in their worlds of experience, which in turn entails that there are many distinctly local global worlds.

People now build relationships which can just as well be transnational as local, and we are connected through the increasingly integrated global economy, the planetary threat of climate change, the hopes and fears of virulent identity politics, consumerism, tourism and media consumption. One thing that it is not, incidentally, is a homogenised world society where everything is becoming the same. Yet, in spite of the differences and inequalities defining the early twenty-first-century world, we are slowly learning to take part in the same conversation about humanity and where it is going.

In spite of its superior research methods and sophisticated tools of analysis, anthropology struggles to come properly to terms with the world today. It needs help from historians, sociologists and others. The lack of historical depth and societal breadth in anthropology has already been mentioned, and a third problem concerns normativity and relativism. For generations, anthropologists were, as a rule, content to describe, compare and analyse without passing moral judgement. The people they studied were far away and represented separate moral communities. Indeed, the method of cultural relativism requires a suspension of judgement to be effective. However, as the world began to shrink as a result of accelerated change in the postwar decades, it increasingly became epistemologically and morally difficult to place ‘the others’ on a different moral scale than oneself. The de facto cultural differences also shrank as peoples across the world increasingly began to partake in a bumpy, unequal but seamless global conversation. By the turn of the millennium, tribal peoples were rapidly becoming a relic, although a dwindling number of tribal groups continue to resist some of the central dimensions of modernity, notably capitalism and the state. Indigenous groups have become accustomed to money, traditional peasants’ children have started to go to school, Indian villagers have learned about their human rights, and Chinese villagers have been transformed into urban industrial workers. In such a world, pretending that what anthropologists did was simply to study remote cultures, would not just have been misleading, but downright disingenuous.

The instant popularity of the term ‘globalisation’ coincided roughly with the fall of the Berlin wall, the beginning of the end of apartheid, the coming of the internet and the first truly mobile telephones. This world of 1991, which influences and is being influenced by different people (and peoples) differently and asymmetrically, rapidly began to create a semblance of a global moral community where there had formerly been none, at least from the viewpoint of anthropology. Ethnographers travelling far and wide now encountered indigenous Amazonian people keen to find out how they could promote their indigenous rights in international arenas, Australian aborigines poring over old ethnographic accounts in order to relearn their half-forgotten traditions, Indian women struggling to escape from caste and patriarchy, urban Africans speaking cynically about corrupt politicians and Pacific islanders trying to establish intellectual copyright over their cultural production in order to prevent piracy.

In such a world, the lofty gaze of the anthropological aristocrat searching for interesting dimensions of comparison comes across not only as dated but even as somewhat tasteless. Professed neutrality becomes in itself a political statement.

What had happened – apart from the fact that native Melanesians now had money, native Africans mobile phones and native Amazonians rights claims? The significant change was that the world had, almost in its entirety, been transformed into a single – if bumpy, diverse and patchy – moral space, while the anthropologists had been busy looking the other way.

In this increasingly interconnected world, cultural relativism can no longer be an excuse for not engaging with the victims of patriarchal violence in India, human rights lawyers in African prisons, minorities demanding not just cultural survival but fair representation in their governments. Were one to refer to ‘African values’ in an assessment of a particular practice, the only possible follow-up question would be ‘whose African values’? In this world, there is friction between systems of value and morality. There can be no retreat into the rarefied world of radical cultural difference when, all of a sudden, some of the ‘radically culturally different’ ask how they can get a job, so that they can begin to buy things. The suture between the old and the new can be studied by anthropologists, but it must be negotiated by those caught on the frontier, and in this world, the anthropologist, the ‘peddler of the exotic’ in Geertz’s (1986) words, cannot withdraw or claim professional immunity, since the world of the remote native is now his own.

Contradictions

Many useful and informative books have been written on globalisation since around 1990. Some of them highlight contradictions and tensions within the global system that are reminiscent of the dialectics of globalisation as described here – George Ritzer (2004) speaks of ‘the grobalization of nothing’ (his term ‘grobalization’ combines growth and globalisation) and ‘the glocalization of something’, Manuel Castells (1996) about ‘system world’ and ‘life world’ (in a manner akin to Niklas Luhmann), Keith Hart (2015) contrasts a human economy with a neoliberal economy, and Benjamin Barber (1995) makes a similar contrast with his concepts of ‘Jihad’ and ‘McWorld’. In all cases, the local strikes back at the homogenising and standardising tendencies of the global.

The extant literature on globalisation is huge, but it has its limitations. Notably, most academic studies and journalistic accounts of global phenomena tend to iron out the unique and particular of each locality, either by treating the whole world as if it is about to become one huge workplace or shopping mall, and/or by treating local particularities in a cavalier and superficial way. The anthropological studies that exist of globalisation, on the other hand, tend to limit themselves to one or a few aspects of globalisation, and to focus too exclusively on exactly that local reality which the more wide-ranging studies neglect. These limitations must be transcended dialectically, by building the confrontation between the universal and the particular into the research design as a premise: For a perspective on the contemporary world to be convincing and comprehensive, it needs the view from the helicopter circling the world just as much as it needs the details that can only be discovered with a magnifying glass. The macro and the micro, the universal and the particular must be seen as two sides of the same coin. One does not make sense without the other; it is yin without yang, Rolls without Royce.

In order to explore the local perceptions and responses to globalisation, no method of inquiry is superior to ethnographic field research. Unique among the social science methods, ethnography provides the minute detail and interpretive richness necessary for a full appreciation of local life. This entails a full understanding of local interpretations of global crisis and their consequences at the level of action. Moreover, there is no such thing as the local view. Within any community views vary since people are differently positioned. Some gain and some lose in a situation of change; some see loss while others see opportunity. But none can anticipate the long-term implications of change.

While ethnography is the richest and most naturalistic of all the social science methods, it is not sufficient when the task at hand amounts to a study of global interconnectedness and, ultimately, the global system. The methods of ethnography must therefore be supplemented. Ethnography can be said to be enormously deep and broad in its command of human life-worlds, but it can equally well be said that it lacks both depth and breadth, that is historical depth and societal breadth. A proper grasp of the global crises, in other words, requires both a proper command of an ethnographic field and sufficient contextual knowledge – statistical, historical, macrosociological – to allow ethnography to enter into the broad conversation about humanity at the outset of the twenty-first century. Since human lives are lived in the concrete here and now, not as abstract generalisations, no account of globalisation is complete unless it is anchored in a local life-world – but understanding local life is also in itself inadequate, since the local reality in itself says little about the system of which it is a part.

It is only in the last couple of decades that the term ‘globalisation’ has entered into common usage, and it may be argued that capitalism, globally hegemonic since the nineteenth century, is now becoming universal in the sense that scarcely any human group now lives independently of a monetised economy. Traditional forms of land tenure are being replaced by private ownership, subsistence agriculture is being phased out in favour of wage work, TV replaces orally transmitted tales and, since 2007, UN estimates suggest that more than half the world’s population lives in urban areas (expected to rise to 70 per cent by 2050). The state, likewise, enters into people’s lives almost everywhere, though to different degrees and in different ways.

It is an interconnected world, but not a smoothly and seamlessly integrated one. Rights, duties, opportunities and constraints continue to be unevenly distributed, and the capitalist world system itself is fundamentally volatile and contradiction-ridden, as its recurrent crises, which are rarely predicted by experts, indicate. One fundamental contradiction consists in the chronic tension between the universalising forces of global modernity and the desire for autonomy in the local community or society. The drive to standardisation, simplification and universalisation is always countered by a defence of local values, practices and relations. In other words, globalisation does not lead to global homogeneity, but highlights a tension, typical of modernity, between the system world and the life-world, between the standardised and the unique, the universal and the particular.

At a higher level of abstraction, the tension between economic development and human sustainability is also a chronic one, and it constitutes the most fundamental double bind of twenty-first-century capitalism. Almost everywhere, there are trade-offs between economic growth and ecology. There is a broad global consensus among policy makers and researchers that the global climate is changing irreversibly due to human activity (mostly the use of fossil fuels). However, other environmental problems are also extremely serious, ranging from air pollution in cities in the Global South to the depletion of phosphorus (a key ingredient in chemical fertiliser), overfishing and erosion. Yet the same policy makers who express concern about environmental problems also advocate continued economic growth, which so far has presupposed the growing utilisation of fossil fuels and other non-renewable resources, thereby contradicting another fundamental value and contributing to undermining the conditions for its own continued existence.

This globally interconnected world may be described through its tendency to generate chronic crises, being complex in such a way as to be ungovernable, volatile and replete with unintended consequences – there are double binds, there is an uneven pace of change, and an unstable relationship between universalising and localising processes. Major transformations engendered by globalisation are those relating to the environment, of the economy, and of identity. They are interconnected and relatively autonomous, although the fundamental contradiction in the global system, arguably, is the conflict between growth and sustainability; these three crises share key features, and they are perceived, understood and responded to locally across the world.

The perspective I am developing concerns these transformations. It represents a critical perspective on the contemporary world since it insists on the primacy of the local and studies global processes as inherently contradictory. I also aim to make a modest contribution to an interdisciplinary history of the early twenty-first century with a basis in ethnography. By this, I mean that it is misleading to start a story about the contemporary world by looking at the big picture – the proportion of the world’s population who are below the UN poverty limit; the number of species driven to extinction in the last half-century; the number of internet users in India and Venezuela – unless these large, abstract figures are related to people’s actual lives. It is obvious that 7 per cent economic growth in, say, Ethiopia does not automatically mean that all Ethiopians are 7 per cent better off (whatever that means), yet those who celebrate abstract statistical figures depicting economic growth often fail to look behind the numbers. They remain at an abstract level of scale, which is not where life takes place. Similarly, the signing of an international agreement on climate change, which took place in Paris in December 2015, does not automatically entail practices which mitigate climate change. So while trying to weave the big tapestry and connect the dots, the credibility of this story about globalisation depends on its ability to show how global processes interact with local lives, in ways which are both similar and different across the planet.

This is a story of contemporary neoliberal global capitalism, the global information society, the post-Cold War world: The rise of information technologies enabling fast, cheap and ubiquitous globa...