![]()

1

Background

The name Kurdistan (“Land of the Kurds”) first appeared in Arabic historical writing in the twelfth century, referring to the region where the eastern foothills of the Taurus Mountains meet the northern Zagros range.1 Estimates of the number of Kurds in the world vary considerably, but the most realistic range from 35–40 million; of that number, about 19 million live in Turkey, 10–18 million in Iran, 5.6 million in Iraq, 3 million in Syria, 0.5 million in the former Soviet Union, and about 1 million in Europe.2

The Kurds are the third largest ethnic group in the Middle East, after Arabs and Turks. Today, the area of Kurdish settlement, while relatively compact, straddles Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Syria. The region is of strategic importance due, among other things, to its wealth in water. The Tigris and Euphrates rivers, which supply water for Syria and Iraq, flow through the Turkish part of Kurdistan (Bakûr).

Linguists agree that the Kurdish language belongs to the Iranian branch of the Indo-European family, although Kurdish differs significantly from Persian. There is no common, standard Kurdish language, nor even a standard alphabet or script, owing in part to the division of Kurdistan and to the bans on Kurdish language in the various states. Kurdish can be divided into five main dialects or dialect groups: Kurmancî, the southern dialects (Soranî, Silemanî, Mukrî), the southeastern dialects (Sinei, Kimanşah, Lekî), Zaza (sometimes considered a separate language), and Guranî.3 These dialects are so different that speakers can’t readily understand each other.

As to the Kurdish people, we have no certain knowledge of their origin. Researchers, nationalists (both Kurdish and Turkish), and even the PKK have all offered theories, depending on ideological orientation. Kemalism, the official state ideology of Turkey, upholds the “indivisible unity of the State with its country and its nation.”4 According to Kemalism, all citizens of Turkey are Turks, and any aspiration to recognition of a non-Turkish identity is persecuted as separatism. Turks insist that the Kurds descended from the Turkic peoples.

Many Kurds, for their part, consider the ancient Medes their forebears. The PKK’s first program, issued in 1978, states, “Our people first attempted to reside on our land in the first millennium BCE, when the Medes, progenitors of our nation, stepped onto the stage of history.”5 When Kurds try to legitimize their rights as a nation to live in Kurdistan, their arguments tend to rest on territorial settlement rather than consanguineous ancestry.6 But assumptions about continuous Kurdish settlement and descent from the Medes entered the collective understanding long ago.

1.1 Geography of Rojava

During the Ottoman Empire (1299–1922), nomadic Arabs entered the area that is now northern Syria, where they encountered the local Kurds. A central trade route connected Aleppo with Mosul and today’s southern Iraq. Between the two world wars, Kurds and Christians fleeing persecution in Turkey settled here. Together with the region’s nomads, they make up the bulk of Rojava’s population today.

In 1923, the victors in World War I created the 511-mile (822-kilometer) border dividing Syria and Turkey. This arbitrary line was drawn between Jarabulus and Nisêbîn (in Turkish, Nusaybin) along the route of the Berlin-Baghdad Railway.

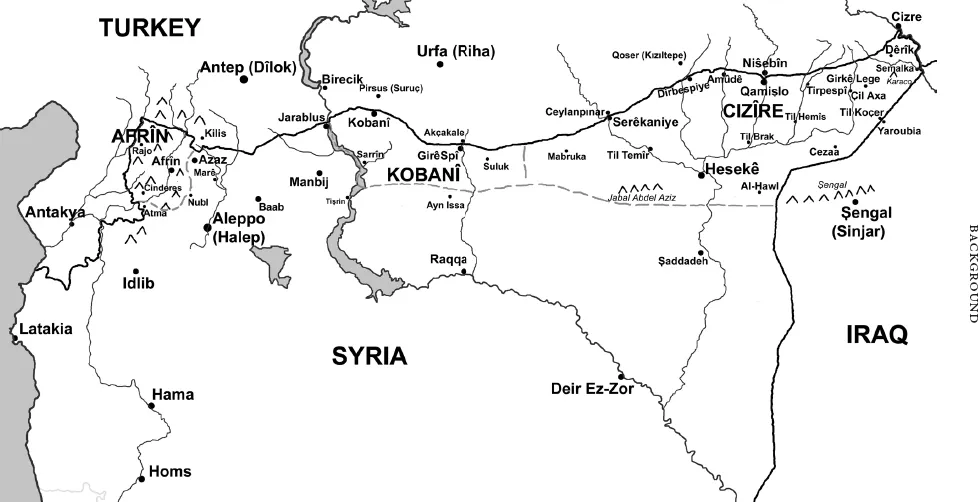

Three islands of mostly Kurdish settlement lie just south of that border. The easternmost is Cizîrê, which also abuts Iraq for a short stretch of the Tigris; the middle island is Kobanî, and the westernmost is Afrîn. Due south of Cizîrê, in Iraq, lie the Şengal mountains (also called Sinjar), which are inhabited by Kurdish Ezidis.

In July 2012, during the Syrian war, the Kurdish movement was able to liberate these three majority-Kurdish regions from the Ba’ath regime. In January 2014, these three regions declared themselves cantons and embarked on the task of establishing a Democratic Autonomous Administration.7 Each canton is currently under the administration of a transitional government. In March 2016, the Federal System of Rojava/ Northern Syria was declared [see 6.9], encompassing the three cantons and some ethnically mixed areas that had recently been liberated from IS.

Figure 1.1 Rojava’s three cantons: Afrîn, Kobanî, and Cizîrê

Afrîn Canton

Afrîn (in Arabic, Afrin), the westernmost canton, is bounded by the Turkish provinces to the north (Kilis) and west (Hatay). Covering about 800 square miles (2,070 square kilometers), it includes eight towns—Afrîn city in the center, then Şêrawa, Cindirês, Mabata, Reco, Bilbilê, Şiyê, and Şera—and 366 villages. Afrîn canton also encompasses the highland known as Kurd Dagh (“Mountain of the Kurds”; in Kurdish, Çiyayê Kurd or Kurmanc; in Arabic, Jabal al-Akrad), which rises westward to the Turkish border and southward and eastward to the Afrîn River, extending slightly beyond. Kurd Dagh is 4,163 feet (1,269 meters) high.8

Afrîn city was founded at a junction of nineteenth-century trade routes. In 1929, its population numbered approximately 800, but by 1968 it had risen to about 7,000 and in 2003 to 36,562.9 At the onset of the Syrian civil war in 2011, the canton’s population was estimated at 400,000, but once the attacks began, many refugees from Aleppo immigrated to Afrîn, boosting the population to 1.2 million.

Most of the inhabitants are Sunni Muslim Kurds. Additionally, about 8,000 Alevi Kurds live in Afrîn, mostly in the northern town of Mabata,10 where a small number of Turkmens also live. A number of Ezidi Kurd villages contain between 7,500 and 10,000 inhabitants, which are called here Zawaştrî. According to the canton’s foreign relations board president, Silêman Ceefer, about 10 percent of the population is Arab. In contrast to the other cantons, aşîret (tribes) no longer play a significant role here.

Afrîn’s terrain is mostly upland, having been settled continuously since antiquity and unthreatened by nomads. It differs in this respect from the two other cantons, which came under the plow in the period between the world wars.11 The climate is Mediterranean with average annual rainfall of 15–20 inches. In the lowlands, Afrîn’s deep, red soils are cultivated intensively, using groundwater pumps powered by diesel. Wheat, cotton, citrus fruits, pomegranates, melons, grapes, and figs are harvested, but the main crop is olives; by some estimates, the canton has more than 13 million olive trees. Beyond the region, the olives are renowned for their high quality.12

Afrîn, under the Syrian administrative system, is part of the Aleppo Governorate. It declared Democratic Autonomy on January 29, 2014. The assembly elected Hêvî Îbrahîm Mustafa board chair, who in turn appointed Remzi Şêxmus and Ebdil Hemid Mistefa her deputies.13

Kobanî Canton

Some 61 miles (98 kilometers) east of Afrîn lies Kobanî (in Arabic, Ayn Al-Arab). Situated at about 1,710 feet (520 meters) above sea level, it is economically significant for grain cultivation. The Euphrates, which provides most of Syria’s water, marks the canton’s western boundary; its waters reach their highest levels in April and May, after the North Kurdistan snowmelt.14 Due to its border location and its rich freshwater resources, Kobanî canton is of great strategic importance.

Its capital, Kobanî city, was founded in 1892 as a company town during the construction of the Berlin-Baghdad Railway. The name Kobanî is thought to be a corruption of the German word Kompanie (company). The artificial Syrian-Turkish border, drawn in 1923, divided the city: the Turkish border town Mürşitpinar (in Kurdish, Etmenek), north of the railroad, was formerly a suburb of Syrian Kobanî. Northeast of Mürşitpinar, the nearest town is Suruç (Kurdish Pirsûs), in Urfa province. While Kobanî was under Syrian occupation, it had an Arabic name, Ayn Al-Arab, which means “spring” or “eye of the Arabs.”

Kurdish aşîret long lived in the Kobanî region. Many of them were nomadic.15 During the twentieth century, Kurdish refugees fleeing persecution in Turkey made Kobanî their home. Turkmens also live in Kobanî, and Armenian refugees settled here as well, fleeing persecution by the Ottoman Empire, but most left in the 1960s for Aleppo or Armenia. At the time of the 2011 Syrian uprising, an estimated 200,000 people lived in Kobanî region.16 During the Syrian civil war, the massive migrations within Syria expanded the population to around 400,000. As for Kobanî city, before 2011, it had 54,681 inhabitants, mostly Kurds, but it now has more than 100,000.17

On July 19, 2012, Kobanî city was the first in Rojava to expel the Ba’ath regime. Kobanî canton declared autonomy on January 27, 2014. The head of Kobanî’s executive council is Enver Muslîm, who appointed Bêrîvan Hesen and Xalid Birgil his deputies. Like Afrîn canton, Kobanî canton, under Syrian administration, is part of the Aleppo Governorate.

In late 2013, IS attempted to capture the canton and the city, but the YPG and YPJ [see 8.1 and 8.2] repeatedly repulsed its attack. In mid-September 2014, the Islamist militias commenced another major offensive on the city. Isolated from...