![]()

1

Milbus: A Theoretical Concept

The concept of Milbus was defined at length in the introduction, as a ‘tribute’ drawn primarily by the officer cadre. As was explained, this portion of the military economy involves the unexplained and undocumented transfer of financial and other resources from the public and private sectors to individuals, through the use of the military’s influence. Milbus as a phenomenon exists in many countries. However, the size of the ‘tribute’ and the consequent level of the military fraternity’s penetration into the economy are directly proportional to the military’s control of politics and governance, and the nature of civil–military relations in a particular country.

This chapter identifies six distinct types of civil–military relations, each dependent on the political strength of the state. The theoretical model presented here revolves around the concept of a politically strong state that is known for its stable pluralist tendencies. The military fraternity’s ability to penetrate the state and society or establish its hegemony is determined by the strength of the political system. A weak polity is a sure sign of a weakened state, and therefore greater intrusion of the armed forces at all levels of the economy, political and societal system. The various civil– military relations models presented are relevant for understanding the intensity and scope of the military’s economic exploitation. Although all militaries vie for resources, their exploitation will increase according to the extent of their political influence.

CIVIL–MILITARY RELATIONS FRAMEWORK

The state is an important subject in political science literature, and there are numerous prisms through which analysts have looked at it. The most important dimensions are its structure, functions and the capacity to perform its roles. From a structural standpoint, a state is described as:

an organization that includes an executive, legislature, bureaucracy, courts, police, military, and in some cases schools and public corporations. A state is not monolithic, although some are more cohesive than others.1

Like a human body, a state is composed of a set of organs meant to perform certain functions. The link between a state’s structural components and its functions is defined as:

a complex apparatus of centralized and institutionalized power that concentrates violence, establishes property rights, and regulates society within a given territory while being formally recognized as a state by international forums.2

Similarly, Charles Tilly has given a list of seven core functions that states perform:

• state making

• war making

• protection

• extraction

• adjudication

• distribution

• production.3

The ‘statist’ literature focuses in particular on the state’s capacity to deliver. In its relationship with the society or people at large, the state is perceived as a ‘supra’ entity that exercises dominance over other competing institutions such as the family, community, tribe and the market.4 Hence, the state’s strength is gauged by its capacity to deliver certain services to the society. Conversely, the state’s capacity is also determined by its control over the society.

The relative strength of the various institutions and their relationships have an impact on the capacity of the state, and this is what makes the state relatively strong or weak. In this study, the state’s capacity is determined not only by its capability to perform these functions, but also by the relationships between the various players. States that allow multiple players to negotiate their share of political influence and national resources are considered stronger than those where political debate is limited or arrested through the military’s influence. In other words, the framework does not treat the state as a monolith that decides issues with a ‘singular’ mind, but as a set of relationships that determine the allocation of resources according to their relative power.5

In fact, the relative power of the multiple players, their relationship with each other, and their ability to freely negotiate their interests are key features of the politically strong state identified in the theoretical framework presented in this chapter. The relative political power that various players have to compete for resources ultimately shapes the allocative process. The competition also generates tension amongst the various competitors, because of the strife and uncertainty that is characteristic of the struggle accompanying the allocation of resources.6

In a nutshell, the state’s capacity is determined by the nature of interaction between the various stakeholders, and the plurality of the political process determines the direction of the allocative process, and the peculiar objective of the state. The purpose of a state is essentially that of an arbiter providing direction to the relationships between the players. Therefore, there are four basic dimensions in the study of the state: (a) the nature and competing interests of stakeholders, which (b) affects the structure of the state, which (c) in turn determines the capacity of the state, and (d) defines its role. This order could be reversed, creating a cyclical rather than a four-tiered structure. To structure this in reverse, a state’s role could conversely have an impact on its capacity, influence its structure and affect the links between the stakeholders.

This basically means that the strength of a state, or what distinguishes a strong state from a weak one, is not just its capacity to complete certain tasks, but its ability to regulate relationships that can help it achieve the set of specified objectives.7 The state thus moves beyond Tilly’s conception of a supra-entity that exercises dominance over other competing institutions such as the family, community, tribe and the market.8

It is equally important to look at the power game that is played to control the state. Competition between the various actors and their interests lies at the heart of the state–society relationship. It is this competition that shapes politics.9 Although there is no perfect formula for all players to get the share they deserve or desire, it is vital to have a political environment that allows the possibility of competition. A pluralist political system provides greater opportunity for the state to co-opt people rather than coerce them to support the official policy perspective. Moreover, the pluralist political structure strengthens the larger civil society to negotiate its rights with the state. Some authors see a state’s stability in the context of its ability to dominate civil society.10 However, in this study, state stability and control, which was the focus of a number of authors on Latin America like Guillermo O’Donnell and Juan Linz,11 is not the key determinant of the strong state. Rather, it is the state’s ability to allow multiple actors to play, and provide a relatively level playing field for the purpose, that ensures the development of a state–society relationship based more on consent than coercion. It must be remembered that states use both coercion and consent to fulfil their functions.

Therefore, the present framework is centred around political pluralism as a primary feature of state–society relations and for evaluating the strength of the state. Established and institutionalized democracy is viewed as a basic method of expression of pluralism and for accommodating multiple interests. Furthermore, electoral democracy as an established norm is the basic minimum prerequisite. These preconditions automatically exclude democracies in transition and states where the military manipulates politics from the back seat from being seen as strong states. Electoral democracy is primarily viewed as a tool or an indicator of a political culture that supports pluralism. It must also be noted that pluralism and democracy are not used in a normative sense. These concepts are essential for an environment where multiple actors can negotiate and renegotiate both political and economic space. The environment is geared not to allow the military or any other player to permanently suppress any ‘competitive claimants’.12

Nor does pluralism undermine sensitivity to the quality of power relationships in a state, since the model takes social cleavages into account. While the framework recognizes the primacy of the state as an instrument of policy and for delivering certain goods to civil society, such as security and development, it does not support turning the state into an instrument of class domination or the supremacy of a particular group. In short, the framework of defining a strong state makes use of the state-corporatist concept of ‘enforced limited pluralism’13 or ‘inclusionary’ corporate autonomy.14 This allows for a strong state from a functional standpoint as well as admitting multiple players or power centres.

Political pluralism as expressed by democratic political rule is essential for two reasons. First, politically, it serves as a security valve against a military takeover of the state and society, or the domination of a strong group or clique. Since the military is a country’s primary organized institution trained in the management of violence,15 it has greater capacity to exercise coercion, and the organizational capacity to dominate civilian institutions.16 Having the capacity to coerce people, the armed forces have a natural edge over other players to dominate the state and society, especially in a non-democratic environment. The military are key players in policy making in all parts of the world. The national security agenda makes it imperative for the political society and policy makers to bestow a special status on the armed forces and their personnel. However, if unchecked the military can dominate all other stakeholders through their sheer organizational strength and power. In fact, the military can become the state itself, as will be shown in the case study of Pakistan. A strong state, on the other hand, is known for treating its armed forces as one of many players, and as an instrument of policy that can be used both internally and externally.

A democratically strong state is at the core of this theoretical model. As we move away from this fulcrum, the strength of the state gradually diminishes, and the weakening political structures may be dominated by political parties, individuals, military regimes or warlords. The peculiar nature of civil–military relations eventually determines the extent to which a military will exploit national resources.

A TYPOLOGY OF CIVIL–MILITARY RELATIONS

There are six identifiable typologies of civil–military relations:

• civil–military partnership

• authoritarian-political-bureaucratic partnership

• ruler military domination

• arbitrator military domination

• parent-guardian military domination

• warlord domination.

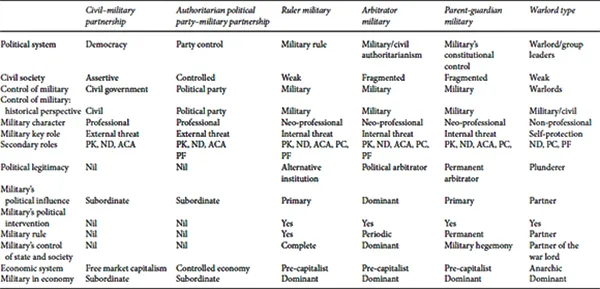

Since the relative power of the political system establishes the strength of the state, which in turn determines the military’s capacity to penetrate the political, social and economic realm, each typology is distinguished by the political and economic system, nature of the civil society, and the level of military’s penetration into the polity, society and economy (see Table 1.1).

In the first type, the military is subservient to civilian authorities. This is due to the strength of the civil institutions and civil society. The system is known for its free market economy, which allows the military to gain advantages through partnership with the dominant political and economic players rather than to operate independently. The armed forces are distinguished by their professionalism, which includes subservience to the civilian authorities.

The military of the second category is similar in terms of its dependence on civilian authorities. However, the armed forces draw their power from the dominant political party, individual leader/s, or the ruling dispensation. Despite the fact that the economy is not structured on a free-market principle, the military does not operate on its own but benefits from its association with the party/leader. The armed forces are primarily professional except that they have a relatively greater role in internal security and governance.

Table 1.1 Civil-military relations: the six typologies

Key: PK: Peacekeeping, ND: Assistance in natural disasters, ACA: Assistance to civilian authorities in domestic emergencies, PC: Political control, PF: Policing functions

The next three categories show different forms of military domination. This is because of the praetorian nature of the societies and the historical significance of the armed forces in power politics. The secondary roles of such militaries include policing functions and political control. The key difference between the three types is in what has been defined here as the military’s stated political legitimacy.

The term ‘legitimacy’ does not refer to civil society’s acceptance of the military’s role, but to the mechanism through which the military justifies its political influence. So while the ruler-type military presents itself as an alternative institution that has to control the state, the arbitrator type rationalizes its dominant role as a political and social arbitrator that steps into governance to correct the imbalance created by the political leadership. The parent-guardian type, on the other hand, uses constitutional mechanisms to consolidate its presence as a permanent arbitrator. The permanent role of an arbitrator is meant to secure the state from any internal or external threats posed by outside enemies or domestic actors who might weaken the state through their indiscretion. The warlord type, which is the final category, presents an extreme case of an anarchic society, where the military loots and plunders in partnership with dominant civilian players.

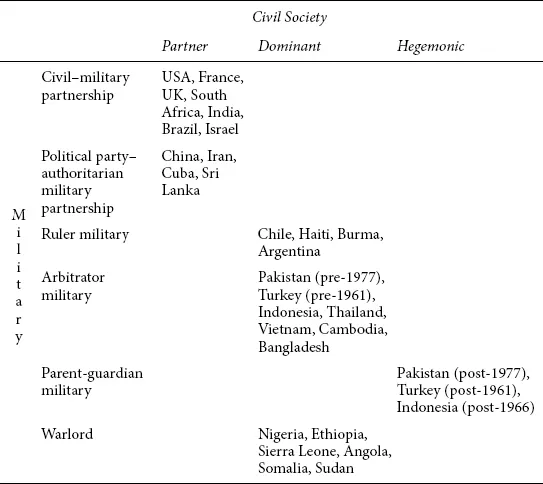

A strong political system or political party control will force the military to take a subservient role. In such cases the role of the armed forces will be defined by the civilian leadership and primarily limited to external security. The role is significant because it determines the level of the military’s penetration into the state and society. Internal security roles tend to increase the military’s involvement in state and societal affairs. The armed forces’ overall penetration, on the other hand, influences the political capacity of the state. In a nutshell, the typologies summarize all the possible interactions between a state and society and its armed forces. (See Table 1.2 for an overview of the comparative types.)

THE CIVIL–MILITARY PARTNERSHIP TYPE

This type is found mostly in stable democracies known for a strong and vibrant civil society and sturdy civilian institutions. The political environment is known for firm civilian control of the armed forces. Historically, the militaries are subservient to the civilian government and are considered as one of the many players vying for their share of resources. The militaries customarily do not challenge civilian authority because of their sense of professionalism and restricted scope to do so. Hence, the armed forces are professional in the true Huntingtonian sense: a strong corporate culture and submission to civilian authorities. This kind of professionalism is inherently different from the ‘new professionalism’ of praetorian militaries in Latin America, South-East Asia and other regions.

Table 1.2 Types of civil–military relations

The primary role of militaries in this category is fighting external threats. The armed forces get involved in internal security duties as well, but that is mainly at the behest of the civilian authorities or under their firm political guidance. The military’s sense of professionalism and restriction to an external security role can be attributed to the strong civil society...