![]()

Part I

Military Industrial Complex – Power, Myths, Facts and Figures

![]()

1

How the West’s Addiction to Arms Sales Caused the 2008 Financial Crisis

In 2008 Western capitalism collapsed.

Beginning with the failure of giant banks such as Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns, within a year European countries such as Iceland and Greece were teetering on the brink of bankruptcy. Stock markets crashed and gold markets soared as some of the most famous names in global commerce – AIG, Morgan Stanley, RBS (The Royal Bank of Scotland) – contemplated their own oblivion. Across the world, governments responded by spending trillions of dollars to support a financial system that was once synonymous with buccaneering free-market capitalism. To pay for these bailouts, many states decided to slash social expenditure even as the banks immediately resumed the payment of multi-million-dollar bonuses to their staff.

Much was written about the causes of the disaster. Some blamed the greed of individual bankers, whose poor decisions had exposed their institutions to a rash of failed loans, particularly in the US housing market. Some blamed the Western governments, either for failing to regulate the financial system or for imposing too much regulation, depending on the analyst’s politics. Some said the investment scene had become too atomised and complex, a result of exotic new securities and derivatives representing diverse risks.

Doubtless these explanations were correct, as far as they went. But all were superficial. None addressed the underlying, structural causes of the economic cataclysm. They did not explain the presence of huge amounts of liquidity in Western capital markets, nor did they account for the astonishingly low interest rates set by the US Federal Reserve. Most importantly, few of the explanations linked what had happened to the financial markets back to the real economy, the place where base materials are cut from the ground, refined and entwined, marketed and sold.

A MYSTERIOUS BOOM

In 2003, a boom began in the United States. Its catalyst was a financial measure that many Americans thought they would never see in their lifetimes. In July that year the head of the US Federal Reserve, Alan Greenspan, slashed the benchmark US interest rate to just 1 per cent. This interest rate controlled the cost of borrowing across the American economy, but it also influenced decisions well beyond the nation’s borders. Borrowing money had never been cheaper.

Banks began lending mortgages to people who would never have had access to such large loans in the past, a housing market that came to be known as ‘sub-prime’. These mortgages were broken down into new types of security that could be traded among banks, which used complex derivatives to ‘hedge’ the very obvious risks that sub-prime lending presented. Across the Union, trailers were swapped for condos, beach huts sprang up on the shores of the Great Lakes, existing homeowners withdrew equity from their properties as if they were giant ATMs. The profits of retailers soared as Americans rushed to purchase their goods with what seemed like an unlimited line of cheap credit.

But where was the cheap money coming from?

The benchmark interest rate reflects how easy it is for a government to borrow money. Government bonds are one place that people with surplus cash can park their money to protect it from inflation. Savers tend to purchase government bonds in times of economic uncertainty, for instance during a recession. Bonds are seen as a safe bet – if the government runs out of money, it can simply print more. Capitalist theory dictates that when demand for bonds is strong the government does not need to offer an attractive interest rate (or ‘yield’) on the debt. This keeps the cost of borrowing low across the economy, which helps to boost investment and propel the country out of recession.

Conversely, during a boom investors prefer the quick gains to be made on the stock market. They tend to ignore stodgy, low-risk government bonds. So, to entice investors to purchase its debt, the government is forced to offer a higher rate of interest. This increases the overall cost of borrowing and cools the booming economy. On paper, the capitalist model should be a perfectly self-correcting, self-regulating system.

That, at least, was the theory.

By 2003 the US Federal Reserve no longer relied on this logic to borrow, if it ever had. This was because Washington had discovered an almost limitless new supply of cheap credit. It was this bottomless well of cheap money that had allowed Greenspan to cut his benchmark rate to record lows, and it was this bottomless well in which the US financial markets would drown in the financial collapse of 2008.

OVERLOAD

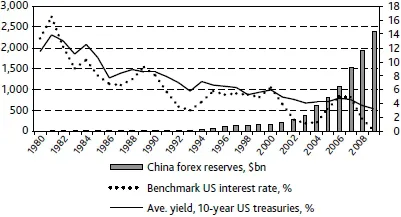

For over 25 years the People’s Republic of China had been moving away from communism towards an export-led economic model. Following the return of Hong Kong to China in 1997 the Chinese economy began to accumulate reserves of foreign currency at an accelerated rate (see Figure 1.1). Foreign exchange reserves are a marker of a country that sells more to the outside world than it buys from it. As more and more container ships left Shanghai laden with plastic goods and cheap electronics, China rapidly became the world’s workshop.

Figure 1.1 Too Much Chinese Money

It was China that was providing the US with its seemingly endless quantities of cheap credit.1,2,3 By 2009 the gap between US sales to China and what it had bought from China had reached a staggering $227 billion.4 China used these leftover dollars to buy more US Treasury bonds, ensuring that US interest rates stayed low, and ensuring that American citizens spent more and more on Chinese goods. China and the US were locked in an economic death spiral, hurtling towards the 2008 collapse.

US officials blamed this vicious cycle on China for pegging its currency, the Yuan, to the dollar at a fixed rate. Were the Chinese currency allowed to float freely, they argued, it would appreciate in value, making it more expensive for Americans to buy Chinese goods and thereby correcting the trade gap. There were two major problems with this argument. China’s currency was artificially cheap in all its export markets, not just the US – yet it was only China’s trade with the US that became so dramatically unbalanced.5 Secondly, from 2005 onwards China allowed the Yuan to appreciate by more than 20 per cent.6 The trade imbalance with the US continued to grow unabated. Many economists conceded that monetary reform was a sideshow; something else was going on.7

What was it about the structure of US exports that was causing the imbalances? Why did China end up investing so much money in US Treasury bonds? Why did the economic imbalances become so lethal, and why was the situation allowed to culminate so badly?

It is wrong to suggest that China deliberately created a crisis in Western capitalism. In fact, Beijing would have much preferred to invest its surplus dollars in a very different way. When it came to its leftover trillions, China had three choices. It could buy US Treasury bonds. It could purchase US goods and services. Or it could acquire US corporations. Options two and three would have reduced the trans-Pacific imbalances which inflated the various bubbles that burst in 2008. However, there was a problem. The US refused to sell China the goods, services and corporations that it wished to buy, because what China wanted to buy was the US military-industrial complex.

WHY IKE WAS RIGHT

January 2011 saw the 50th anniversary of President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s farewell address to his nation. The anniversary reinvigorated discussion of what the former Supreme Allied Commander meant when he warned his countrymen to ‘guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.’

Half a century later commentators on both the left and right of the political spectrum have lined up to dismiss and downplay Eisenhower’s warning. In the conservative National Review, Vincent Cannato claimed that the political Left has been especially eager to appropriate the Republican general’s words for political purposes. He concluded that Eisenhower was merely urging fiscal restraint, a warning against wasteful Pentagon spending and procurement policies, rather than pointing towards a construct with autonomous political power.8

Some liberal pundits were equally dismissive. David Greenberg argued in Slate that Ike’s address had been completely misunderstood, calling fulminations against the military-industrial complex lazy, hackneyed, and histrionic. Greenberg condemned what he called the ‘mad embrace’ of Eisenhower in recent decades by anti-war leftists and so-called realists. While he conceded that the president had worried America could become a garrison state, Greenberg mocked those who saw the military-industrial complex as a conspiratorial, demonic system. Instead, he claimed that Eisenhower’s military-industrial complex merely represented an outsize special interest which promoted extravagant military spending.9

DEFINING OUR TERMS

Given such scepticism, it is important to define the exact nature of the military-industrial complex. The United States is a useful case-study. Until ...