![]()

Part 1

The Basics of HE Funding

The fundamentals of higher education funding are set out here. Chapter 1 covers the recent policy history culminating in the events of 2010: the formation of the Coalition

government, the delivery of the Browne review into undergraduate funding, and the subsequent decision to cut direct funding to universities. Chapter 2 looks at tuition fees and why the average fee

in 2012 was above the government’s desired figure of £7,500 per year. Chapter 3 examines student loans and their repayment terms.

![]()

1

The Mass Higher Education System and its Funding

To understand the new level of tuition fees in England and the cuts to direct grant funding of institutions, one needs to understand the recent history of the sector, which has been transformed in the last 20 years or so by an initially rapid expansion. This has placed the funding of students and the financing of universities at the centre of policy debate and brought the Treasury into the dominant position when it comes to decision-making.

THE ADVENT OF A MASS SYSTEM

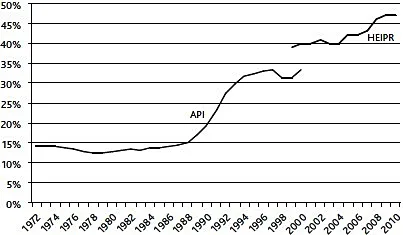

Expansion of higher education began under Kenneth Baker, Secretary of State for Education in the Thatcher government. Initiated by the 1988 Education Reform Act and the 1992 Further and Higher Education Act, participation rates by age cohort leapt from around 15 per cent in 1988 to close to 35 per cent within a decade. Contrary to popular misunderstandings, this participation rate was not the simple result of polytechnics being reclassified as universities: those attending polytechnics were already included in the higher education participation statistics. But, the polytechnics and their successor institutions did expand, some dramatically: Hatfield Polytechnic, as it became the University of Hertfordshire, saw an expansion in its student numbers from around 5,000 to over 30,000 during the 1990s.

Figure 1.1 illustrates the dramatic spike in participation between 1988 and the mid 1990s. The two lines on the graph reflect different methods of measuring the initial participation rate in higher education. The lower line shows the Age Participation Index (API) of those under 21 as a percentage of the cohort, which has more recently been replaced by the Higher Education Initial Participation Rate (higher line) which covers those aged between 17 and 30.1 Doubts about API methodology mean that is only used here to illustrate the relative change in participation.

There are now over one million Home undergraduates studying full-time and many more part-time, not to mention postgraduates and students from outside the EU. Despite populist and popular grumblings, this approach, expanding to meet demand, has largely found cross-party support, underpinning both Baker’s initiative and Tony Blair’s 1997 election campaign mantra of ‘Education, Education, Education’, which set a new target of 50 per cent of school leavers moving on to higher education. In some ways, the advent of a mass system is the consummation of the 1963 Robbins Report which argued that ‘courses of higher education should be available for all those who are qualified by ability and attainment to pursue them and who wish to do so’.2

FUNDING THE MASS SYSTEM

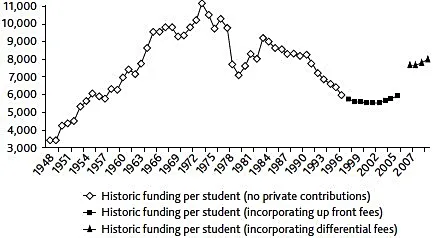

The flipside to expansion is the question of funding. Figure 1.2 shows the funding per student in 2006/7 prices between 1948 and 2009.

Funding per student declined precipitously in real terms from 1981 and declined even faster with the expansion of the late 1980s and early 1990s. The last two major reviews of higher education, Dearing (1997) and Browne (2010), focused on this question of funding. Dearing recommended a means-tested upfront fee of £1,000 per year, the introduction of which stabilised the per-student resourcing (black squares in Figure 1.2). This move established the principle of ‘co-payment’, whereby the benefit accruing to the private individual from higher education should be reflected in more than taxation on higher earnings.

In 2004, Labour pushed through the contentious policy of ‘variable fees’, winning its passage by only four votes despite its large parliamentary majority. A new maximum fee was set at £3,000 per year. (Thereby introducing the legislation used by the Coalition for its snap vote in December 2010.) These fees, however, were no longer paid upfront and were instead covered by an expansion of the student loan scheme, which had previously been restricted to loans to cover some of the costs of maintenance while studying.

All institutions soon moved to this new fee level and no pricing variation occurred at undergraduate level. It is important to note that, in contrast to the latest reforms, these fees did not replace any central funding but provided additional resourcing to universities and college and so restored per-student funding to a level comparable to the 1980s (black triangles in Figure 1.2). Advocates of fees have in mind the manner in which their introduction broke with government rationing of resources.

THE BROWNE REVIEW

In 2009, Peter Mandelson, then Labour Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills, published a report, Higher Ambitions, which set out a vision for a more entrepreneurial higher education sector less reliant on central funding.3 (In the course of 2010, the Labour government announced a reduction in the higher education budget for 2010/11 of £135 million.)

Subsequently, a review panel was established, led by John Browne, formerly chief executive of BP. Its remit was to set in place a sustainable system of financing higher education that would lighten the burden on public finances, but also enable the sector to expand to meet the current unmet demand for undergraduate education. Its final recommendations were published in October 2010 as Securing a Sustainable Future for Higher Education, after the change in government.4 A short report of 60 pages, it had eight main recommendations:

1. Massive reduction in direct grants including the removal of direct public funding for arts, humanities and social science degrees.

2. The abolition of the current tuition fee cap allowing universities to set whatever fees they wished.

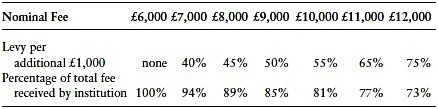

3. A levy scheme, or ‘soft cap’, requiring universities to return an increasing proportion of those higher fees to central coffers for each thousand pound increment above £6,000 (see Table 1.1). It was designed to dissuade universities from setting fees indiscriminately, since universities do not bear the cost of non-repayment on loans, the Exchequer does.

Table 1.1 Browne’s proposed fee levy

Source: Securing a Sustainable Future, 2010, p. 37

4. A change to the parameters of the loan scheme so that repayments would only begin once the graduate was in receipt of more than £21,000 per annum from 2016.

5. The introduction of real interest rates on the loans, i.e., above inflation, which were previously subsidised against the government’s cost of borrowing.

6. The removal of all institutional recruitment caps (bar medicine and dentistry).

7. An increase in maintenance loans, grants and other financial support to full-time students.

8. Extending access to loans for tuition fees to part-time students.

On the one hand, the proposed system would be more ‘sustainable’ by having more funding return as loan repayments. On the other hand, removing all ‘supply-side’ restrictions on universities by abolishing fee and recruitment caps would mean on average that institutions would receive more income providing demand remained constant.

While there was consensus on the objectives of the reform of higher education funding (increasing participation, improving quality of provision, and making the funding solution sustainable), the solution of opening up competition by removing all direct public support and hiking fees was not unanimously received. Indeed the sole piece of research commissioned by the review revealed that: ‘Most full-time students and parents ... believed that the government should pay at least half the cost of higher education. This is because the personal benefits of higher education were seen by many to match the benefits to society.’ This striking finding did not appear in the final report and had to be revealed through a Freedom of Information request produced by Times Higher Education.5

The report argued that it had balanced the trade-off between public and private benefits accruing to the individual, but its private sector-style solutions reflected the background of its Chairman and several of its members, with CVs that included stints at the management consultancy firm McKinsey.

THE GOVERNMENT’S RESPONSE

Although the previous Labour administration had commissioned the Browne review, when it reported in October 2010 many of its suggestions were acceptable to the Conservatives now in government. The first recommendation, cutting direct central funding to institutions, was accepted. The Comprehensive Spending Review later in October announced the reduction in central grants to universities and colleges: around £3 billion per year by 2014/15 when the new regime is to be fully implemented. BIS will no longer offer any direct funding for degrees in the arts, humanities, business, law and social sciences, thus removing one impediment to competition from private providers. (The new higher fees will replace lost funding and therefore do not significantly alter the per-student funding seen in Figure 1.2.)

In a formal response to Browne the following month, the proposed interest rate taper and the higher loan repayment threshold (£21,000 in 2016 as opposed to £15,000 today) were both accepted. However, the ‘levy’, Item 3 above, proved unpopular with universities who wanted to keep more of, and more control over, the higher fees they expected to receive. In addition, the removal of a maximum tuition fee cap (Item 2) was unacceptable to the junior Coalition partners, the Liberal Democrats. Their 2010 Election manifesto had committed to abolishing tuition fees; they had actively campaigned around the issue and had signed an NUS pledge promising to vote against any increase.

Instead, a compromise was reached with a new maximum tuition fee (and no levy). Through a snap vote held in the House of Commons on 9 December 2010, the maximum fee allowed was raised from £3,375 per year to £9,000 for undergraduates commencing their studies in September 2012. Almost two years later, Nick Clegg, the Deputy Prime Minister and Leader of the Liberal Democracts, felt compelled to issue a filmed apology to the nation: not for the policy, but for signing the NUS pledge.

It was a political coup to bring that vote forward using existing secondary legislation before publishing a White Paper and detailed proposals on the actual functioning of the loan scheme and the new market in undergraduate recruitment. No detail could be examined; the House of Lords, which voted the following week, was deprived of its now conventional role as a revising chamber.

Had the new maximum fee moved through Parliament slowly, accompanying primary legislation, it may have been lost and split the Coalition. As it was the vote narrowly passed. This abuse had the desired effect of spiking the guns of those opposing the remainder of the plans and confusing potential activists about just what had been won or lost on that occasion.

MISTAKE AND COMPROMISE

Browne had warned the government not to cherry-pick from his proposals and to treat them as a coherent whole, but political compromises and mistakes frustrated this further. With no levy as per Browne to encourage universities to set lower fees, the government proposals contained only the bare maximum of £9,000 per year. In early 2011, most universities moved to set t...