![]()

1

Introduction

Most politicians are known for what they did in life rather than for the way they died. In this, as in so many things, Salvador Allende was an exception. More people know about his overthrow than know about what his government did, or how he became president of Chile. Allende’s life, like that of so many other revolutionaries, has been stripped of context and reduced to the symbolism of his last moments when, surrounded by the smoke and flames of a bombed and burning presidential palace, he took his own life.

Allende’s last words to the Chilean people were probably the greatest words of farewell ever uttered by a political leader, and they had an immense impact on people around the world. Yet there is much more to the life of Salvador Allende than the last seven hours, or even the last three years of his life. These were the culmination of his political ambitions, and the triumph of his political methods, but they were also the last stage in a long process of struggle and organisation that had its roots in the beginning of the twentieth century at around the time Allende was born. Allende’s death and the overthrow of his government are often told as a dramatic tragedy, but Allende’s significance for Chile and for the wider world also lies within the story of his life, intertwined in history of the popular movement that he led.

Chile’s Popular Unity government was of tremendous interest during the early 1970s. The successful implementation of a ‘peaceful road’ happened to chime with the USSR’s public recognition that a ‘peaceful road’ to socialism was possible, and it was of great interest to a Western European and North American left that shared its political methods if not always its revolutionary goals. The Chilean process was also of great interest to the Third World and the countries of the Non-Aligned Movement, who recognised in Allende’s Chile a country that struggled with the same problems of exploitation and underdevelopment. Allende’s victory in September 1970 was therefore an event of global importance, which inadvertently and inevitably dragged Chile towards what one of Allende’s erstwhile friends called ‘the precipice of the Cold War.’1

Allende’s victory was just as important to his ideological opponents. For the Chilean elite it marked the failure of constitutional means to hold back social pressure for fundamental changes. For Christian Democrats it highlighted the abject failure of their ‘revolution in liberty’, the effort to make deep social changes within capitalism, and while aligned with the United States. Further afield it was also the death knell of Washington’s Alliance for Progress, a decade-old programme of economic and military measures designed to prevent revolution in the region and ostensibly promote ‘development’ through free trade and political liberalism. By the late 1960s it was clear that while it had successfully prevented revolution, often through dictatorship and repression, it had failed to achieve anything else. Chile, with its relatively well-developed political system and strongly rooted political parties, was therefore an important example of a civilian US-aligned government. Allende’s election thus hit an exposed nerve. The United States had been actively involved in preventing a Marxist government in Chile since the early 1960s, spending millions of dollars and penetrating Chilean politics at every level. This made it even worse that Salvador Allende, a self-proclaimed Marxist, had been elected and that to top it all one of the main pillars of his government was the region’s largest and best-organised Communist Party. The United States had helped overthrow Latin American governments for much less.

It was not just the failure of the Alliance for Progress and its efforts to subvert Chilean democracy that irked the United States. Allende’s government had an economic and foreign policy programme that put it on a collision course with Washington. The nationalisation of copper and other natural resources created an example that could be emulated by many other Third World countries, and its foreign policy directly challenged US efforts to align Latin American countries behind Washington by claiming Chile’s inalienable right to determine its own foreign policy, free of US dictates – a complete rejection of the Monroe Doctrine that had justified US interventionism in Latin America since 1823. For the United States the appearance of a Marxist government was completely unacceptable. Détente between superpowers was one thing, allowing Chile to ‘go communist’, as Kissinger put it was another. The US government was not the only enemy of the Popular Unity. Other right-wing regimes, transnational corporations and individual businessmen from around the world were also opposed to it. In Brazil, where in 1964 the military had overthrown Joao Goulart, a president with similar aspirations to Allende, there was particular opposition. The Popular Unity was therefore at the centre of an ideological conflict that went beyond spheres of influence and economic interest and to the heart of a global struggle.

The Popular Unity government and its overthrow were thus a defining moment of Cold War politics. It frightened and inspired in equal measure. In Italy its overthrow led to the ‘historic compromise’ between Communists and Christian Democrats, in France to the construction of a Socialist-Communist coalition led by Francois Mitterand. Many people learned from studying the Popular Unity and its overthrow, and many more also heard about it first hand from the hundreds of thousands of Chileans the dictatorship forced into exile. Chile thus became a global revolutionary reference.

Allende’s government has also been a reference point for today’s progressive Latin American governments, with Venezuela the best-known example. These all won government through electoral means, and are to one degree or another implementing gradual transformations of society and economy. Although in a different period in history, they too are attempting to build forms of socialism. In this process, the spectre of Chile has loomed large and history has seemed to repeat itself – US funded opposition, bosses lock-outs, efforts to split trade unions and the popular movement, coups promoted in the military, media hysteria and political pressure in the international arena. Success in overcoming these challenges has owed much to lessons learned from Allende’s overthrow.

Salvador Allende was a tireless champion of Latin American integration and self-determination, picking up the legacy of the liberators of Chile, and by extension, the legacy of Simon Bolivar. Allende helped establish the Andean Pact, and in a region full of dictatorships he sought to build foreign relations based on mutual respect and non-interference. The Popular Unity was therefore an ideological precursor to the integrationist efforts being made in the region today.

In Chile Allende’s life and legacy were forbidden topics during the long dictatorship that followed his overthrow. Yet the two processes have created modern Chile. Pinochet’s regime was the antithesis of Allende’s, but it was unable to extinguish the memory of the Popular Unity, and it was unable to destroy what one of the Junta members called ‘the cancer of Marxism’. Nor did it completely undo Allende’s lifelong project to nationalise the copper industry, which remains the mainstay of the Chilean economy. Therefore the story of Allende’s life, and the story of the popular movement that he helped to shape, are key to understanding what Chile is today.

Henry Kissinger once told a visiting Chilean foreign minister that, ‘nothing important can come from the south. History has never been produced there.’2 Yet Allende’s political thought, and his efforts to build a revolutionary coalition remain relevant wherever there are people seeking to transform their societies away from capitalism. It was this potential that was one of the causes of Allende’s overthrow. The 1970s was an ideologised period, and the language of Marxism was well known, hotly debated by left-wingers. In his own time Allende was called a ‘reformist’, and accused of ‘parliamentarism’. Today, in a world without ‘isms’ we can see the revolutionary content of his thought more clearly, away from what Allende called ‘the cold maze of theory’.3 Throughout his life Allende pushed for a process of revolutionary reformism, to achieve a qualitative change in society. Although others misunderstood him, he never lost sight of this goal. Allende’s life shows that political compromises do not have to be reformist, or aimed at preserving capitalism, and that in fact, reforms, by building upon and within existing structures, can become a revolutionary ‘perestroika’, avoiding the carnage and waste of violent change.

Allende came to lead a vast popular movement, which had three main motors, the country’s two Marxist parties, and its unified trade union movement. As the century progressed Chile developed a rich network of social and political organisations and a profound political culture. Although positioned within the left, Allende was able to appeal to those beyond the popular movement, and this is why he became its pre-eminent figure. Throughout his life Allende sought to ‘cultivate consciousness’, and how Allende was able to do so is the story of the breadth of his political vision, the energy of his political methods, and the charisma of his personality.

In a measure of his importance to Chile, in 2008, 100 years after his birth, the Chilean public voted Allende the greatest Chilean in history. Forty years after his overthrow Allende remains a symbol of a Chile that was and yet could be. Even today Chileans remain divided by the twin legacy of the Popular Unity and the dictatorship that consumed it. Allende feared civil war because of the ‘tremendous and painful’ social and economic scars it would leave, while destroying the ‘national community’. Yet despite his efforts Chile was subjected to a form of civil war from which it has yet to recover.

Because of this Allende has remained a figure of fascination in Chile, and throughout the Spanish-speaking world. Yet few biographies of Allende exist in English, and most of these were written shortly after his death in 1973. Naturally, the emphasis of these works was on the final years of his life and there was an inclination to make the books serve the purpose of solidarity with the victims of the coup. For this reason even the manner of his death was twisted, leading to long years of doubt over the manner of his end. Some aspects of his life, most notably regarding his character and personality were also ignored or overlooked. The many memoirs that have been published by friends and collaborators in the years since allow us today to fill out the picture of Allende’s life as a politician and as a man. Now we can have a much richer, livelier, more human version of this extraordinary man who did so much to shape the destiny of his country, and by doing so has influenced Latin America and the World.

* * *

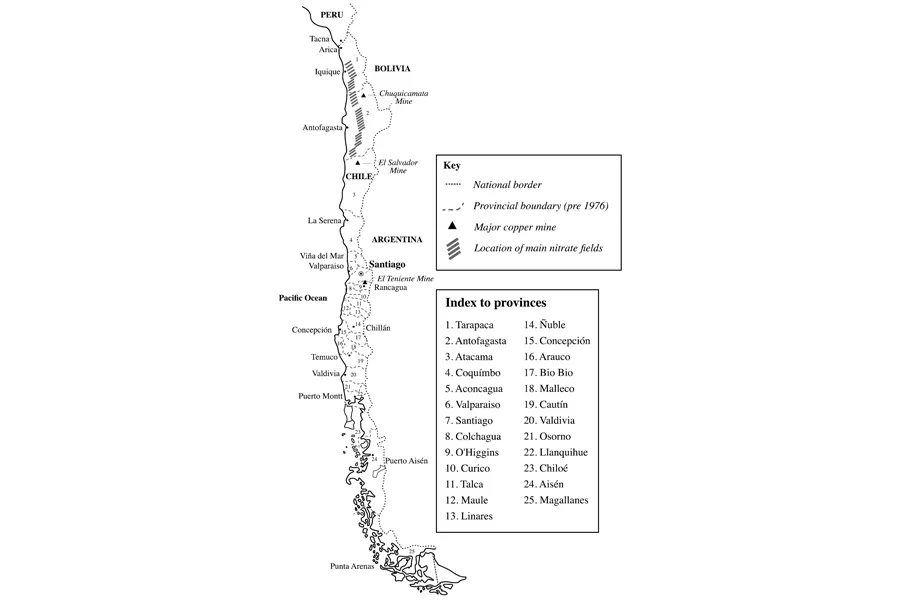

Chile, the land of Salvador Allende’s birth, is a long and narrow country that stretches 5,000 kilometres from the desert border with Peru down through a warm central region, onwards through a temperate southern zone where it begins to break up into islands and fjords. Far to the south, a short distance from Antarctica, it ends in the windswept and rainy plains of Tierra del Fuego. Isolated from the rest of Latin America by deserts and the mountainous spine formed by the high Andes, and facing the vastness of the Southern Pacific Ocean, Chileans have something of an island mentality. Chile’s isolation and distance from world events have made Chileans somewhat self conscious in their provincialism, and very proud of those who have achieved international recognition.

Chile’s original indigenous inhabitants, the Araucanian Mapuches, fiercely defended their independence for 300 years. Their courage and intelligence were admired by Spaniards such as the sixteenth century poet Alonso de Ercilla, who wrote that Chile produced people ‘so remarkable, so proud, gallant and martial, that they have never by king been ruled nor to foreign dominion submitted.’ Chile was a frontier country, and from war and trade the new ‘mestizo’ Chilean arose, a mixture of the Indigenous and Spanish peoples. After independence in 1818 new communities arrived from an industrialising and convulsed Europe, among them Allende’s Belgian grandfather Arsene Gossens, although the majority of these immigrants were Germans. Yet despite this immigration, Chile’s population remained remarkably homogenous, with only 4 per cent of the population being foreign-born in 1907.4

The vast majority of these people worked the land and toiled in the cities, or in mines and nitrate fields. Two contradictory stereotypes arose to describe the typical Chilean: the ‘roto’, and the ‘huaso’. The ‘roto’ (literally ‘the broken one’), the archetypal urban worker, tough, stubborn, cunning, opportunistic and uncouth. A dark-skinned mestizo, the roto was admired as a symbol of ‘chilenidad’ (chileanness), the ‘ethnic basis of the Chilean nation’.5 Yet at the same time the roto was scorned for his poverty and ignorance, and for his lack of respect for the law, for his propensity to violence and rebellion, and for drunkenness. All ranks of society saw something of the ‘roto’ in themselves, and so, as Loveman has described, the roto is ‘a complex symbol of chilenidad, that signifies both the misery of the poverty-stricken worker and the ‘viveza’ (opportunism) of those who benefit from his toil.’6 The huaso was originally a poor rural worker and cowboy of a ‘primitive roughness’, within whom the ‘screaming of the indian’ subsisted.7 Increasingly, rural landowners began to associate with this symbol of Chilean identity, completing it with flamboyant poncho, ornate wooden stirrups and silver spurs. These stereotypes developed through the nineteenth century, and were symbolic of Chile’s increasing reliance on its growing mining industry and the agriculture of its central valley. This was the ‘pueblo’, the people, who during the nineteenth century had begun to mobilise to improve their quality of life.

The Chile that Allende grew up in was the product of events that occurred during the late nineteenth century. Towards the end of this century Chile had come into conflict with its northern neighbour, Bolivia, over the allocation of income from nitrate mines that were located in Bolivian territory, but mostly manned and owned by Chileans. In 1879 the conflict escalated into war as Bolivia sought to impose taxes on foreign owned mines, including Chilean ones. Chilean troops moved north and rapidly conquered Bolivia’s maritime provinces. Peru, which had a secret treaty with Bolivia, entered the war but was also defeated. By 1883 Chilean forces had occupied Lima. The result of the war was the annexation of Bolivia’s maritime province, as well as some of southern Peru. Chile continued to occupy the Peruvian province of Tacna until 1925, when it was evacuated after the failure of a long-running and unpopular process of ‘chileanisation’. The conflict left Chile in possession of the Atacama Desert, with its immense mineral riches, and a heightened sense of Chilean superiority over its neighbours, reinforcing ideas regarding the martial qualities of the ‘Chilean race’. The Chilean army then turned south, and troops fresh from the deserts of the north completed the subjugation of the Mapuche indigenous people, opening up their lands for colonisation.

The War of the Pacific stimulated the industrialisation of Chile, thanks to the need to supply the army. After the war the workforce dedicated to nitrates and other forms of mining in the north expanded rapidly as both Chilean and foreign companies moved in. Chile experienced a population shift northwards, at the same time as this workforce became recognisably proletarian. Meanwhile the growth of industry and mining also stimulated changes within the elite. The new industrial elites sought greater political representation than Chile’s aristocratic system allowed them. By the 1880s many of these wealthy mine owners had begun to question free trade, and were beginning to argue for forms of protectionism for Chile’s nascent industry. The elite was also divided over religious issues, and the role of the Catholic Church in society. In 1886 José Manuel Balmaceda came to the Presidency, initiating the largest programme of public works yet seen with income from the nitrate mines. However, Balmaceda gradually alienated the landowning aristocracy, as well as a large number of Chilean nitrate impresarios, who feared his talk of the creation of a national nitrate company. This also threatened foreign nitrate barons, most notably, John Thomas North. North then began to use his fortune to undermine Balmaceda’s government. Balmaceda did not seek mass political support, and his repression of Chile’s first general strike in 1890 lost him much of what he had. Personality conflicts and problems dispensing patronage among his Liberal followers then ensured Balmaceda’s increasing isolation.8 In 1891 Congress declared his government unconstitutional and the navy rebelled, a short and bloody civil war followed, and Balmaceda’s forces were defeated.

Following 1891, Chile was governed by a ‘parliamentary republic’ where most power lay with parliament, where ‘elite interest groups dressed up as political parties vied for power and state patronage.’9 Although restrictive in many ways, the parliamentary republic, founded by the revolution against Balmaceda’s ‘tyranny’, did allow the development of free speech and some level of political opposition. The state role in the economy was reduced and foreign investment in nitrates increased. Thanks to income from nitrates taxes were gradually withdrawn. The income from mining and nitrates continued to stimulate development, and urbanisation increased, as did the role of mining in the economy. By 1907 44 per cent of the population was urb...