![]()

1

The Unknown War

For half a century the Cuban people have endured almost every conceivable form of terrorism. The bombs that have destroyed department stores, hotel lobbies, theaters, famous restaurants and bars—people’s lives. The second worst act of air terrorism in the Americas, resulting in the deaths of 73 civilians. An exploding ship in Havana Harbor, killing and injuring hundreds. Attacks on defenseless villages. Teenagers tortured and murdered for teaching farmers to read and write. Biological terrorism causing the deaths of more than 100 children. The psychological horror that drove thousands of parents to willingly send their children to an unknown fate in a foreign country.

Since the earliest days of the revolution, Cuba has been fighting its own war on terrorism. The victims have been overwhelmingly innocent civilians. The accused have been primarily Cuban-American counter-revolutionaries—many allegedly trained, financed and supported by various American government agencies. The justification for this aggression has been framed in the language of ideology, the battle between capitalism and socialism, good and evil. The acts have been described as “disrupting vital resources,” “targeting strategic interests,” “propaganda efforts.” The implication is that military or political objectives have been hit. In reality the majority of the targets have been neither military nor political.

Cuba’s war on terrorism has been largely unrecognized by the international community in spite of the material destruction and loss of human life. The government has documented approximately 800 terrorist acts inside Cuba since 1960—hundreds more have occurred against officials and commercial operations outside the country. Each assault has personally affected dozens, if not hundreds; some acts have touched the whole island nation of 11 million. It is hard not to find someone who doesn’t have a story to tell of a relative or friend who has been a victim of terrorism. The personal toll has been calculated at 3,478 dead and 2,099 injured.

There are many reasons why few outside Cuba have not heard about this deadly conflict. Cuba is considered to be “the other side.” They have a social-political system diametrically opposite to western capitalism. Cuba represents the official enemy. And when it is the United States of America that applies that designation, there is little likelihood this history will be recognized within government elite circles or examined in the mainstream media.

The other reason may be more revealing. Those accused in the vast majority of the acts have been members of anti-Castro militant organizations originating from south Florida. Alpha 66, Omega 7, Commandos F4, are but a few of the more infamous Cuban-American groups that have devoted themselves to the violent overthrow of the Castro regime. The rationalization for these attacks is to bring freedom and democracy to the Cuban people, regardless of the resultant death and destruction. The root cause of the violence is based on the loss of political and economic influence. These groups were organized in the months immediately following the revolution’s triumph in January 1959, when the elite of the American-supported Batista dictatorship fled Cuba for the safe confines of Miami, bringing with them organizational skills, financial backing and a visceral hatred for Castro.

Politically the first wave of exiles fit snugly within the US position towards the revolution—hostility, resentment and determination to bring Cuba back under its fold, by whatever methods necessary.

While extreme groups such as Alpha 66 often maneuvered on the fringes of the law, other more respected entities have been accused of also being involved in counter-revolutionary activities, such as Brothers to the Rescue and the Cuban American National Foundation (CANF). The Foundation was established in the 1980s with the assistance of President Ronald Reagan, and has since received government funding in the millions of dollars. Both groups have been implicated in this terrorist war through allegations of financial and material assistance to the more militant groups. And in some cases direct involvement, as in the incident of the biological attack on one of Cuba’s most historic tobacco farms by a Cuban-American member of the Brothers, who happened to turn out to be a double agent, according to the farm’s famous owner.

Most of these organizations have operated with impunity in the Miami area, many individual members are well-known and admired in the community. Two of the most infamous are Orlando Bosch and Luis Posada Carriles, masterminds of the bombing of Cubana Airlines flight 455 which killed 73 passengers in 1976. Both currently live unmolested in Miami.

Posada Carriles was trained in demolition and guerilla warfare by the CIA in the 1960s, and continued to be an agency operative until the late 1970s. He was involved in the Bay of Pigs invasion, fought with the Contras in Nicaragua, and was arrested in Panama in 2000 for his plan to blow up an auditorium where Castro was lecturing in front of hundreds of students. Posada Carriles has at various times talked extensively to the press about his involvement in terrorist activities against Cuba. In a 1998 interview with the New York Times,1 he spoke in detail about the series of 1997 bombings against Cuban hotel and tourist facilities, which he claimed officials at the Cuban American National Foundation were aware of and helped finance. In the interview he outlined how the explosives were obtained through his contacts in El Salvador and Guatemala, and then carried into Cuba by mercenaries hired by his subordinates.

Carriles admitted the most famous of the hotel bombers, Raúl Ernesto Cruz León, was working for him. It was one of the bombs planted by Cruz León that killed Italian Fabio Di Celmo at the Hotel Copacabana. “That Italian was sitting in the wrong place at the wrong time,” Carriles commented in the Times article.

Carriles represents the physical manifestation of American policy towards Cuba since the revolution, policy that is unlike any other. While the United States has diplomatic relations with communist Vietnam, considers China one of its most important trading partners, and has never unleashed its wrath against such violators of civil and human rights as Egypt or Saudi Arabia, it continues to hold Cuba up for special punishment. The travel restrictions, the economic blockade, the propaganda war and the terrorist acts have persisted against this small island nation. Since the earliest days of Fidel’s victory, America has obsessed over this relatively insignificant third-world country, determined to eliminate the radically different social-economic order instituted by the revolution.

The historical context that has led America to unleash its military, economic and political fury, to allow the launching of thousands of terrorist attacks from its own soil, can be traced back well before Fidel came on the scene. For almost 200 years the United States has looked upon Cuba as part of its natural sphere of influence and has unrelentingly pursued policies to secure that perception. Political and media elites presented this point of view and molded it into historically accepted fact, which became ingrained in the national consciousness. The result is that American dialogue towards Cuba remains consistently confined to narrowly held beliefs.

The certainty that has been most profoundly embedded into the American psyche is over right of possession. The United States convinced itself that ownership of Cuba was natural, preordained, and key to fulfilling vital national expectations. Justifying possession of another country required a sophisticated propaganda campaign. America at various times has portrayed Cuba as a helpless woman, a defenseless baby, a child in need of direction, an incompetent freedom fighter, an ignorant farmer, an ignoble ingrate, an ill-bred revolutionary, a viral communist. These characterizations were designed to demonstrate Cuban inability to control their own country, that to allow them to set up a national government would be misguided at best, dangerous at worst. Only the United States could manage the Cuban population in the proper administration of government, economy and culture. And if any of the locals had the temerity to challenge America’s right of possession, they did so at their own peril. In the modern context, the terrorist war against Cuba has as one of its objectives the destruction of the current regime in order to demonstrate incompetence in selfgovernment; thus facilitating reintegration of American interests on the island.

The idea of custody over Cuba goes as far back as 1823 when Secretary of State John Quincy Adams wrote: “There are laws of political as well as of physical gravitation; and if an apple, severed by the tempest from its native tree, cannot choose but fall to the ground, Cuba, forcibly disjoined from its own unnatural connection with Spain, and incapable of self-support, can gravitate only towards the North American Union.”2

Rationalizations for America’s inevitable wresting the island away from Spanish hands came in abundance. The reasoning ranged from proximity to national security.

California Representative Milton Latham conflated both: “Due to its proximity to our shores Cuba is of vast importance to the peace and security of this country.” He warned of allowing Cuba to pass to any other hands other than American. “This, not from a feeling of ambitions, not from a desire for the extension of dominion, but because that island is indispensable to the safety of the United States.”3

Writer William Mills in 1898 bluntly articulated that “The independence of Cuba is, therefore, an historical absurdity… Nothing but her complete incorporation into our territorial system will allay the menace of her geographical position.”4

With politicians framing the parameters of discussion, and the media in full support, it was an easy matter for the national dialogue to be structured towards the inevitability that America would, and should, own Cuba.

The most opportune chance to control the island presented itself during the last stages of Cuba’s Second War of Independence in 1896, known in North America as the Spanish-American war. After three years of fighting between the Cuban rebels and their Spanish overlords, America entered the fray on the noble quest of bringing “freedom” to the Cuban people. At this point both warring sides were at the end of their efforts and the Spanish were indicating a desire to finally cede real independence to the Cuban people. As Fidel Castro said, lecturing to the United Nations General Assembly in September 1960, “Spain had neither the men nor money left to continue the war in Cuba. Spain was routed.” Cuba, he noted, was on the verge of true sovereignty for the first time in its history.

America saw the Cuban struggle for independence differently—as the best chance to fulfill its own ambitions. After an intensive public relations drive to convince the public of the necessity of entry into the war, helped by the explosion of the battleship Maine in Havana Harbor, United States forces were sent to Cuba in April 1898. Six weeks later the conflict was over. The Treaty of Paris was signed between the United States and Spain on December 10, 1898. There was no Cuban representative at the signing, on the insistence of the American side. This was the start of the historical dialogue that the Cubans had nothing to do with winning their own independence; that national freedom was solely based on the actions of the United States.

Historian Emily Rosenberg described United States intervention as a chivalrous thing, “to provide protection to a woman or to a country—emblematically feminized—that rival men are violating.”5

The portrayal of Cuba as a helpless woman had another implication: that the Cuban men were ineffective, they could not win their war of independence and so by extension were incapable of running their own country.

The March 15, 1889 edition of the Philadelphia Manufacturer described Cuban men as, “Helpless, idle of defective morals, and unfitted by nature and experience for discharging the obligations of citizenship in a great and free republic… Even their attempts at rebellion have been so pitifully ineffective that they have risen little above the dignity of farce.”6

Editorials such as the one that ran in the Manufacturer helped frame the public debate that holding on to the island was the proper thing to do. This despite the expectation of the Cuban side, which believed the Americans would depart gracefully, based on the 1898 Teller Amendment which promised not to annex Cuba but only “leave control of the island to its people.” They were in for a rude shock, however, when the United States decided to keep the island for itself.

American control was represented as desirable as it would bring social stability, political maturity and economic prosperity to the child-like Cubans. Naturally then, the Cubans would acquiesce to the wishes of the adult. In this regard local opinion was made irrelevant, as no right thinking person would reject subservience when it brought so much benefit.

Connecticut senator Orville Platt articulated the view, “No man is bound to adopt a child, as we have adopted Cuba; but having adopted a child he is bound to provide for it.”7

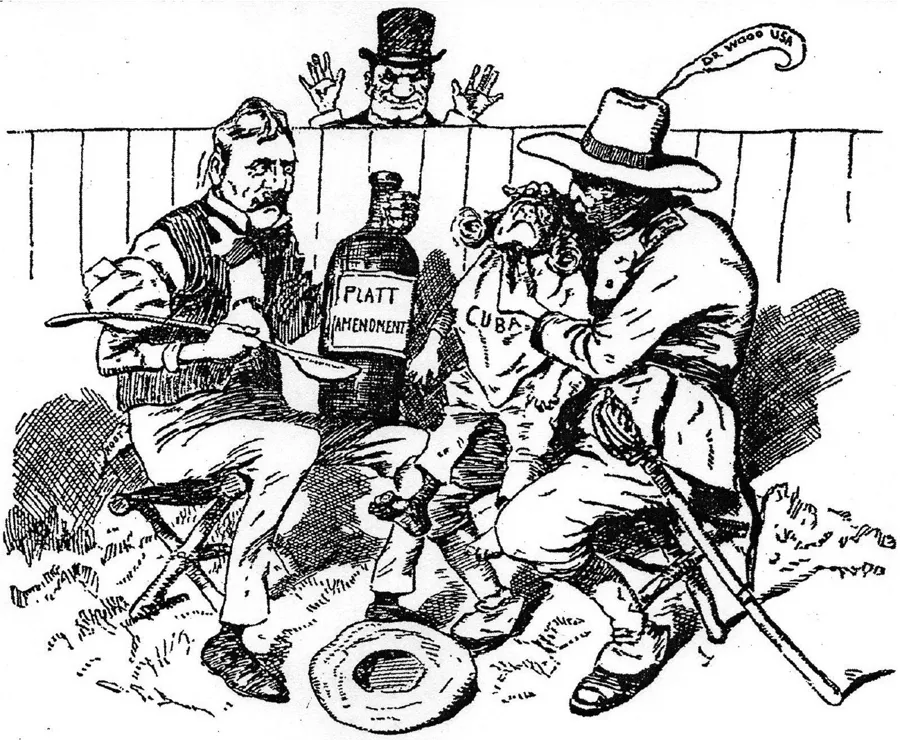

Platt will be forever remembered in the chronicles of modern Cuban–American relations as the man who gave his name to the amendment that best epitomized the policy of wrapping self-interest in the blanket of moral authority. The Platt Amendment was accepted under the strenuous objections of the American-installed Cuban government in 1901. It was finally abrogated in 1934, but by then command was established over all aspects of Cuban social, political and economic life.

The amendment was designed to allow the United States to direct the most important aspects of Cuban society. It was used as a way to ensure that the Cubans would conduct good government with American interests placed first. The other side saw it as an insulting, degrading piece of legislation forced down their throat. It was accepted only when non-compliance would result in the indefinite continuation of the American occupying army. The New York World captured the feelings on both sides in its June 14, 1901 editorial cartoon captioned “Down at Last” showing an American military official holding open the baby Cuba’s mouth while the politician is force feeding a spoonful of Platt Amendment represented by a large bottle of medicine. In the background the American businessman looks on approvingly from behind a large wooden fence.8

Cuba was restricted in a variety of ways under Platt. The amendment gave the Americans control of foreign policy, the right to intervene in national affairs, permission for private businesses to come in and invest in Cuba at favorable conditions and the authorization to purchase land at less than market value, with promotions to “colonize Cuba.”9 The Platt Amendment provided the conditions to permit American commerce to dominate the sugar industry and exercise influence over all other aspects of the economy.

“Down at Last.” Depiction of cuban acceptance of the Platt Amendment. From New York World, June 14, 1901.

The impact of the amendment is still being felt today. Cuba was forced to agree to sell or lease to the United States “lands necessary for coaling or naval stations at certain specified points to be agreed upon.” The Americans wanted a large naval base on the south-east end of the island, now known as Guantánamo Bay. Despite Cuba’s protests, the treaty allows America to continue to own the Bay until both sides agree to closure.

The most hypocritical condition of the Platt Amendment was the one that prohibited Cuba from negotiating treaties with any country other than the United States, “which will impair or to impair the independence of Cuba” or “permit any foreign power or powers to obtain…lodgement in or control over any portion” of Cuba.

That clause betrayed America’s true intentions for Cuba—the United States, a foreign power that was impairing the independence of Cuba, forcing the Cubans to sign a treaty prohibiting them from negotiating treaties to impair their independence. It brought home to the Cubans what Indiana Senator Albert Beveridge snorted in 1900: “Cuba independent. Impossible.”10

The Cubans chaffed under the Platt Amendment, while the Americans criticized the local population for not showing enough gratitude, nor sufficient appreciation for all that was being bestowed upon them. Within that frame was the precept of never acknowle...