- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book tells the story of Pakistan through the lens of the Cold War, and more recently the War on Terror, to shed light on the domestic and international processes behind the global rise of militant Islam. Unlike existing scholarship on nationalism, Islam and the state in Pakistan, which tends to privilege events in a narrowly defined 'political' realm, Saadia Toor highlights the significance of cultural politics in Pakistan from its origins to the contemporary period. This extra dimension allows Toor to explain how the struggle between Marxists and liberal nationalists was influenced and eventually engulfed by the agenda of the religious right.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The State of Islam by Saadia Toor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Islamic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

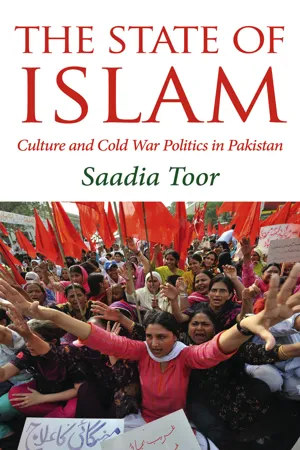

The image on the cover of this book, a contemporary photograph of a women workers’ protest against rising food prices, captures the spirit of a variety of movements that inhabit the political landscape of Pakistan today.1 The cadence of the half-hidden sign in the front that says “Ghareeb Bachao, Ghurbat Mukao” (“Save the Poor, End Poverty”) echoes the beat of a progressive sentiment that was at the heart of the newly de-colonized and independent nation that came into being on 14 August 1947.

Although beset with huge problems and seemingly insurmountable odds, and despite the trauma of the violence of Partition, ordinary Pakistanis at that time were hopeful of forming a society in which they would have a place and a voice. The anti-colonial movement in the subcontinent was suffused with a radicalism that had led many to believe that the departure of the British would herald an egalitarian social system. While the period following Independence was one of contestation over the political and economic soul of the nation, it was one which progressive forces believed they could help shape. This book seeks to offer an account of Pakistani history that foregrounds the important role played by these forces from the very inception of the nation-state.

Today, the Western media has no space for images such as the one on the cover, or for stories that contradict the dominant narrative of Pakistan as a fountainhead of extremism. Alternate frameworks for understanding the country and its people are conspicuously absent from both mainstream media and academic discourse. Within the historiography of the subcontinent, dominated as it is by Indianists, the establishment of Pakistan is projected as the culmination of an essentially religious movement, which destroyed the secular fabric of India.2 The problems that Pakistan faces today—particularly the rise of religious extremism—are thus presumed to be the poisonous fruit of this flawed foundation,3 with parallels often being drawn with Israel which is identified as the only other modern state established on the basis of religion.

This narrative obscures several important facts: first, that the ideology of Muslim nationalism which underpinned the demand for Pakistan embodied an ethnic and not a religious nationalism;4 secondly, that unlike Israel, which was from the very beginning cast as a homeland for all Jews, Pakistan was never understood as the purported homeland for all Muslims but only those of the Indian subcontinent, and finally, that there was a progressive element to the “Pakistan Movement” which came under increasing pressure following the establishment of Pakistan because of the classes which came to constitute the ruling establishment in the new state.

A parallel line of argument posits that Pakistan’s problems can be traced to a confusion over its national identity—that it was, echoing Rushdie (2000: 86), “a place insufficiently imagined.” This confusion (or “insufficiency”) is understood as an indication of the inherent “inauthenticity” of Pakistan’s national project, and is seen as having explanatory power. There are several problems with this analytical framework. First, it assumes that there are, in fact, such things as “authentic” nations and national projects. In doing so, it mis-understands the very nature and purpose of nationalism, thereby participating in the naturalization of a “hugely powerful repertoire and rhetoric of rule” (Corrigan and Sayer, 1985: 197). As the legitimating ideology of the modern nation-state, nationalism is by definition a discourse of power and as such is always deeply contested. Rather than a sign of confusion and inauthenticity, the contentious debates among Pakistani intellectuals over what constituted Pakistani nationalism should be seen as reflecting the vibrant and dynamic nature of the politico-ideological field in Pakistan.

Moreover, to posit the confusions and anxieties reflected in these ideological debates as the source of Pakistan’s past or present problems is deeply flawed. As later chapters in this book show, these confusions could be very productive from the point of view of the Left, which could (and did) propose progressive models for the Pakistani nation-state project. The problem was not ideological confusion, but the active attempts by the Pakistani establishment and its organic intellectuals to marginalize secular and democratic models of the nation-state which they saw as threatening to their interests.

The tendency of the Pakistani establishment to turn to Islam— and, more importantly, to Islamist forces—in order to undermine progressive politics was evident from the very beginning and created the conditions for the increasing power of the religious Right within Pakistani society and politics. Even then, the increase in influence did not proceed in any kind of neat fashion; this is a story of contingencies, contradictions, breaks and spikes. The Ayub regime, for example, went from actively targeting the Jama’at-i Islami to making strategic alliances with it when faced with mass mobilization on the Left. The secular and “socialist” Bhutto contributed to this trend (and set the stage for General Zia ul Haq’s efforts to Islamize Pakistan) by reaching out to the Gulf Arab states for moral and material support, and by choosing to appease the increasingly belligerent religious groups rather than strengthen his working-class base. And it’s worth noting that even Zia ul Haq, a US-backed military dictator and the head of the most brutal regime in Pakistani history, met significant resistance when he tried to operationalize his Islamization project.

The institutional power behind specific ideological projects is far more significant than the inherent persuasiveness of the ideas they embody. The greater a group (or class’s) institutional power, the greater its ability to spread its own message far and wide and to suppress or misrepresent alternatives. Thus, we must look to such things as the balance of power between the different social forces, the confluence of domestic and international political agendas, and the political interests embedded in the various ideological projects in order to understand why a particular set of ideas—of the nation, the state, and (crucially) Islam—seems to “win” over others at any given moment in time. In Pakistan, as in other parts of the Muslim world, the rise of Islamists as a social and political force was engineered both directly, by inducting them into state institutions as Zia did, and indirectly, by “cleansing” the political sphere of their only effective nemesis/counter, the Left. The story of the marginalization/decimation of the Left is thus a crucial part of the story of the Islamization of Pakistan.

Both the anticommunism of the establishment and the turn towards Islam as a means to undermine the Left had an international dimension. During the Cold War, the US establishment believed that Islam, particularly its radical variant, could provide an effective politico-ideological bulwark against communism in Muslim countries generally, and be a thorn in the side of radical nationalist regimes in the Arab-Muslim world. Saudi Arabia’s crucial function in this scheme was as an exporter of a rabidly anticommunist Islamist ideology. These Cold War scenarios were playing themselves out across the Muslim world, and were not unique to Pakistan. What really set Pakistan apart, however, and decisively changed the game, was the US’s proxy war in Afghanistan. It was through this war that violence in the name of Islam became legitimized, the means by which to inflict it became freely available, and the networks through which it was to be operationalized were created.

This book highlights the fact that “Islam” is far from being a monolith, even within the specific context of Pakistan. It has always been and continues to be not only invested with different meanings and associations by different actors, but also articulated with wildly different political projects, and is thereby itself a deeply contested ideological field. The book illustrates the diversity of meanings and political programs associated with “Islam” through Pakistani history—from the modernist Islam of the Muslim nationalists, to the Sunni radicalism of the Jama’at-i Islami to the “Islamic socialism” of Bhutto’s People’s Party. This diversity, along with the popular heterodox forms of Islam indigenous to Pakistan, has been steadily under attack by domestic and international forces invested in a much narrower and far more intolerant version of the “faith.” The book offers an account of this contestation, and draws attention to the growing forces of radicalization and their relationship with the imperialist project, first under the sign of the Cold War and now under the Global War on Terror.

The other goal of this book is to resurrect the important role played by the Pakistani Left from the very inception of the nation-state in challenging both the establishment and the religious Right. While it is usually either ignored or dismissed as irrelevant within the mainstream discourse on Pakistan, the Left’s influence on Pakistan’s culture and politics has been significant and often far greater than its organizational strength would warrant. Many, if not most, of Pakistan’s most well-respected writers, poets, intellectuals and journalists in the early period of its history were affiliated either with the Communist Party or the left-wing Progressive Writers Association, or with both. The fact that they were and continue to be household names bears further testimony to their importance within the cultural and political life of the new state. The most obvious example is that of Faiz Ahmed Faiz, general secretary of the All Pakistan Trade Union Federation, editor-in-chief of Progressive Papers, Ltd. (a family of left-wing periodicals), winner of the Lenin Peace Prize, and Pakistan’s unofficial poet laureate.

While the Pakistani Left has been (often justly) criticized for the strategic errors which it made at various points, these mistakes must not be used to dismiss its contributions, for no other political formation embodied its progressive ideals of anti-imperialism, international solidarity and social justice, a fact that becomes distressingly clear when we look at what has come to pass for “progressive” politics in Pakistan after the decimation of the Left in the 1980s. From the very beginning, members of the Pakistani Left faced hostility, harassment and violence at the hands of the state. Faiz himself was incarcerated several times, but never left Pakistan until Zia ul Haq’s regime. Within Pakistan, the absence of the Left from mainstream accounts of Pakistani history is part of a concerted and ongoing attempt at limiting the political imaginary of the Pakistani people. Outside of Pakistan, these “sanitized” accounts reinforce existing stereotypes about Pakistan and Pakistani society as hopelessly reactionary.

This book is a small attempt to disrupt the mainstream account of Pakistani history by offering an alternative narrative, one which explains Pakistan’s present reality not as an inexorable unfolding of a teleology, but as the result of a complex and contingent historical process with both domestic and international dimensions. It aims to highlight resistance and struggle, and to document the important and historical role played by the Pakistani Left in the culture and politics of the country.

The remainder of this chapter, apart from offering an overview of the book, provides a brief outline of the history of the demand for Pakistan. It lays out the context against which many of the issues that came to inflect the Pakistani nation-state project need to be understood, particularly the development of a Muslim identity beginning in the late nineteenth century and its expression as Muslim nationalism. Most importantly, it highlights the contingencies and contradictions that lay behind the establishment of Pakistan as a separate nation-state.

Almost immediately following independence, the Pakistani establishment realized that East Bengal, with more than half of the population of the new state, and a history of radical politics, posed a potent threat to its corporate interests. In fact, East Bengal embodied almost all the contradictions and tensions which defined the nation-state project at this time: the question of what constituted Pakistani culture, the place of non-Muslim (particularly Hindu) minorities within the nation-state, the essentially non-representative nature of the Muslim League government, and the emerging authoritarianism within the state. Undermining East Bengal and countering its demographic majority thus became the singular focus of the ruling establishment at this time. The opportunistic and contradictory ways in which the Muslim League government deployed “Islam” in order to accomplish this task in this early and formative period of Pakistan’s history are the focus of Chapter 2.

During this same period, an acrimonious debate erupted in West Pakistan between members of the influential and left-wing Progressive Writers Association (PWA) and a group of liberal anti-communist intellectuals who pointedly identified themselves as “nationalists.” Chapter 3 highlights the important role played by the cultural Left in Pakistan in terms of countering the reactionary politics of the establishment and its organic intellectuals, while holding out an alternative, people-centered model of the nation-state.

The story of the cultural Cold War as it unfolded in Pakistan under the martial-law regime of Ayub Khan is continued in Chapter 4. Ayub Khan sought to legitimize his rule by casting himself in the role of the great modernizer. While economic modernization (that is, “development”) was to proceed along the trajectory laid out by the Harvard Advisory Group, the project of social and cultural modernization involved the co-optation of liberal anti-communist intellectuals. Eventually, the contradictions of the economic model of “functional inequality” along with the deeply repressive nature of the regime led to a massive outpouring of dissent, and the consolidation of a left-wing mass movement. As the popularity of the Left became clear, liberal anti-communist intellectuals joined forces with the religious Right in what proved to be an unsuccessful attempt to stem the tide of history.

Chapter 5 charts the dramatic turn-around from the rise of a new revolutionary and mass-based left-wing politics in the late 1960s to Zia’s military theocracy. The Bhutto regime, which linked these two dramatically different periods of Pakistani history, was characterized by contradictory politics in which “socialism” and “anti-imperialism” were officially extolled while the organized Left was systematically repressed. This laid the groundwork for the counter-revolution of General Zia ul Haq, who came to power through a military coup. Zia’s Islamization project sought to “purge” Pakistan of the viruses of secularism and socialism, and managed to transform Pakistani culture and politics in significant ways, despite the substantive and broad-based resistance from democratic forces. The chapter highlights the important role played by feminist poets in articulating a critique of the regime’s retrogressive project.

Often regarded as a “lost decade,” the 1990s were, in fact, a crucial period in terms of the consolidation of a number of processes which had been set in motion during the Zia regime, such as neoliberalism, violent sectarianism and the dramatic erosion of the rights of minorities and women. Chapter 6 focuses on two cases which turned into moments of national crisis and thereby highlighted the complexity of the ideological terrain at this time: the shocking honor killing of Samia Sarwar, murdered by her family in her lawyer’s office for trying to obtain a divorce, and the story of Saima Waheed, a young woman who had married against her family’s wishes. Both cases generated a widespread discourse on national culture and identity, “Islam” and “the West,” and the status and rights of Pakistani (Muslim) women. Among other things, these cases highlight the opportunistic ways in which “Islam” is deployed by those in power—pressed into service when useful, ignored when inconvenient.

The book ends with a discussion of Pakistan today, focusing in particular on the fall-out of the Global War on Terror. While it has become commonplace to point out that Islamic militancy is shrinking the space for progressive politics (and even progressive culture), the nature and internal contradictions of this progressive politics have not been the focus of much analysis. The Epilogue argues that the decimation of the Pakistani Left in the 1980s left a vacuum within Pakistani politics which liberals—with their aversion for mass-based politics and their predilection for technocratic solutions—were unable to fill, and that the present bellicosity of the religious Right is at least partly the fruit of this failure.

Just as the anti-communism of the Cold War enabled the marginalization—via ideological warfare as well as through the use of repressive tactics such as censorship, arrests, disappearances, torture and assassinations—of certain political imaginings threatening to the establishment, the ideological circulation of the Islamic terrorist as the new enemy of freedom and democracy that underpins the War on Terror has similarly enabled the emergence of a reactionary liberal politics within Pakistan. The Epilogue sketches out some of the contours of this politics, and ends by arguing that the only true source of hope for Pakistan lies, as it always did, in the struggles of its working classes.

INDIAN MUSLIMS AND THE POLITICS OF REPRESENTATION

In order to follow the trajectory outlined above, we need to first come to terms with the process through with Pakistan was established, and its roots in a Muslim self-consciousness that began to develop in the nineteenth century. This self-consciousness was itself the product of British colonial politics, which were based on an understanding of Indian society as structured primarily around religious cleavages. British colonialism thus identified religious communities as the basic units of Indian society; in time, this “communal” framework came to structure Indians’ own self-understanding (Pandey, 1990). The everyday experiences of Indians were mediated through a British adminis...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Consolidating the Nation-State: East Bengal and the Politics of National Culture

- 3 Post-Partition Literary Politics: The Progressives versus the Nationalists

- 4 Ayub Khan’s Decade of Development and its Cultural Vicissitudes

- 5 From Bhutto’s Authoritarian Populism to Zia’s Military Theocracy

- 6 The Long Shadow of Zia: Women, Minorities and the Nation-State

- Epilogue The Neoliberal Security State

- Notes

- References

- Index