- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

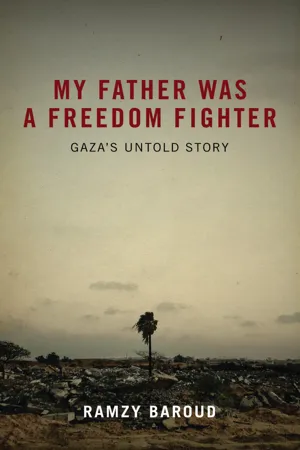

About this book

This book is a personal account of the daily lives of the people of the frontline of the Palestine / Israel conflict, giving us an insight into the deadly, seemingly never-ending rounds of violence. Ramzy Baroud tells his father's fascinating story. Driven out of his village to a refugee camp, he took up arms and fought the occupation at the same time raising a family and trying to do the best for his children. Baroud's vivid and honest account reveals the complex human beings; revolutionaries, great moms and dads, lovers, and comedians that make Gaza so much more than just a disputed territory.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access My Father Was a Freedom Fighter by Ramzy Baroud in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Advocacy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Happier Times

“Why bother to haul the good blankets on the back of a donkey, exposing them to the dust of the journey, while we know that it’s a matter of a week or so before we return to Beit Daras?” he questioned his bewildered wife, Zeinab. Many years later, Grandma Zeinab would repeat this story with a chuckle, as Grandpa Mohammed would shake his head with an awkward mix of embarrassment and grief.

I cannot pinpoint the moment when my grandfather, that beautiful old man with his small white beard and humble demeanor, discovered that his “good blankets” were gone forever, that all that remained of his village were two giant concrete pillars, and piles of cactus. I know that he had never given up hope to return to Beit Daras, perhaps to the same small mud-brick house with the dove tower on the roof.

Beit Daras’s inconsequential present existence would evoke little interest, save two concrete pillars, that once upon a time served as an entrance to a small mosque. Its walls, as those faithful to its walls, are long gone, yet somehow, they still insist on identifying with that serene place and that simple existence. On that very spot, on the shoulder of that small hill, huddled between numerous meadows and fences of blooming cactus, there once rested that lovely little village. And also there, somewhere in the vicinity of the two giant concrete pillars, in a tiny mud-brick home, with a small extension used for storing crops and a dove tower on the roof, my father Mohammed Baroud was born.

It isn’t easy to construct a history that, only several decades ago, was, along with every standing building of that village, blown to smithereens with the very intent of erasing it from existence. Most historic references of Beit Daras, whether by Israeli or Palestinian historians, were brief, and ultimately resulted in delineating the fall of Beit Daras as just one among nearly 500 Palestinian villages that were frequently evacuated and then completely flattened during the war years of 1947–49. It was another episode in a more complicated tragedy that has seen the dispossession and expulsion of nearly 800,000 Palestinian Arabs. For Zionist Jews, Beit Daras was just another hill, known by a code battle name, to be conquered, as it were. But it should be more than a footnote in David Ben Gurion’s War Diaries, or Benny Morris’s volume, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem. It’s more than a few numbers on an endless chart, whether one that documents victims of massacres, or estimates of Palestinian refugees still reliant on United Nations food aid. For Palestinians, its fall is one of many sorrows in the anthology which is collectively known as al-Nakba, or the Catastrophe.

My grandparents never tired of reminiscing about their beloved village. My grandfather, also named Mohammed, was often mocked for failing to understand the depth of his tragedy, by insisting that they leave the “good blankets” behind as he herded his children together to escape the village and the intense bombardment. He died 58 kilometers southwest of Beit Daras, in a refugee camp known as Nuseirat.

Beit Daras provided dignity; Grandpa’s calloused hands and weathered, leathery skin attested to the decades of hard labor tending the rocky soil in the fields of Palestine. It was a popular pastime for my brothers and I to point to a scar on his battered little body so we could hear a gut-busting tale of the rigors of farm-life. Grandpa ran his fingers over the fading scar on the crown of his head and chuckled: “I got this one at dawn, I went to milk the cow, usually your grandmother’s chore, and that cow had it in for me. I squatted behind her, and then everything went black.” Tales of being trampled by the donkey or being run over by a plow: potentially life-threatening injuries were all reduced to humorous anecdotes sure to provoke a flood of laughter from his grandchildren.

Grandpa similarly enjoyed reminiscing on the good old days when he had land, a house, chickens, goats, a strong back—everything he needed to provide for his family. Camp life provided nothing from which to harvest a sense of self-respect. Food that once was the fruit of hours of toiling in his own fields was now provided in a burlap bag by some European country or by the United Nations. Perhaps one of the greatest challenges he faced was enduring a life of idleness. One activity, however, that occupied his time was sitting with other men in the camp and discussing the politics of the day, debating just from whom and when liberation would come. Would their lands back home be ready for planting? Would they be able to rebuild right away?

Later in life, someone would give him a small handheld radio to glean the latest news and from that moment, he would never be seen without it. As a child, I recall him listening to the Arab Voice news on that battered radio, which had once been blue but now had faded to white with age. Its bulging batteries were duct-taped to the back. Sitting with the radio up to his ear and fighting to hear the reporter amidst the static, Grandpa listened and waited for the announcer to make that long-awaited call: “To the people of Beit Daras: your lands have been liberated, go back to your village.” In my life, I only heard my grandpa curse at one reoccurring scenario. His younger son Muneer would make sport of him by running into the room where he would sit and crying out, “Father, they just made the announcement, we can reclaim our land today!” My grandpa would jump from his chair and dash for the radio, but my uncle could not contain his laughter any longer. Knowing that his son had so maliciously fooled him once more, he would point his shaky finger at him and mumble under his breath, “You little bastard,” and would return to his chair to wait.

The day he died, his faithful radio was lying on the pillow close to his ear so that even then he might catch the announcement for which he had waited for so long. He wanted to comprehend his dispossession as a simple glitch in the world’s consciousness that was sure to be corrected and straightened out in time. He was not mindful of balances of power, regional geopolitics, or other trivial matters. But it is not as if Grandpa was not a keen man, for he certainly was in all worldly matters of relevance to his humble existence. But he decidedly refused to entertain any rationale that would mean the acceptance of an eternal divorce from a past that defined every fiber of his being. For him, accepting that the “good blankets” were gone was the end of hope, the end of faith, the end of life. Grandpa Mohammed was a hopeful man, with strong faith. I loved his company, and his pleasant stories of Beit Daras, its simple folk and much happier times.

BEIT DARAS

Located 46 kilometers to the north-east of Gaza City, Beit Daras was a village that was part of the Gaza Province, and mostly consisted of flat, arable meadows. The Gaza Province extended from the Sinai Peninsula in the south, to the al-Ramleh Province in the north, and from Hebron in the east to the Mediterranean Sea in the west. By the end of the British Mandate in Palestine in 1948, the Gaza Province was comprised of 54 villages and three major towns: Gaza City, al-Majdal and Khan Yunis.1 It sat 50 meters above sea level, in a central location bordering the towns of al-Majdal and Isdud, and the villages of Hamameh, al-Sawafir and al-Batani.

It was also close to al-Ramleh and Hebron, and a few hours ride by donkey to the major port city of Jaffa, a trip that my grandfather would make many times during his life in Beit Daras. Before the war of 1948, that central location was a blessing to the people of the village. Unlike nearby villages, the residents of Beit Daras didn’t seek distant markets to sell their produce and livestock. Two markets, Abu Khadra and Abu Kuffeh, the former specializing in produce and the latter in meat and livestock, were two major attractions that made Beit Daras a required journey for buyers and sellers from near and far.

But something else made Beit Daras different from its neighboring villages. To the east of the village, a British police station was erected soon after the British victory over the Turkish army in 1917, a military drive that began in southern Palestine, through Egypt. The station was hardly there to administer the daily affairs of the village, but rather to ensure the safety of a Jewish colony known as Tabiyya.

Fatima al-Haj Ahmed—known as Um ‘Adel—is one of the village’s survivors who was made a refugee in the Gaza Strip. There she lives a very difficult life. Eighty years old, Um ‘Adel recalls her life in Beit Daras with a fondness that seems to grow with age. Her apolitical narrative transcends time. She told me that the residents of Tabiyya were peaceful, and generous. “They used to come to the market and buy meat and vegetables. Poor things, they knew nothing about agriculture. So we helped them,” she told me, so nonchalantly, and as if nothing has occurred in the intervening years to mar this fond memory.2 When I asked Um ‘Adel of the language the dwellers of Tabiyya spoke, she gave me a perplexed reply: “What do you mean? What other language would they speak but ours?”

Beit Daras’s Jewish neighbors seemed to also excel in the local dialect spoken by the villagers of Beit Daras. But two issues puzzled the people of Beit Daras: the occasional sounds of gunfire coming from behind the colony’s fortified walls, and the strong and strange bond that united the British police and the Jewish residents of Tabiyya, despite the fact that no communal violence had ever stained the thus-far neighborly relationship between the people of Beit Daras and those of Tabiyya. In a voice interrupted by an occasional nervous giggle, Um ‘Adel told me:

Every night a bunch of English officers would come patrolling our streets from the direction of the kubaniya [the Jewish colony]. They would ride their horses recklessly in the village. Then we all start running into the alleyways seeking shelter. I used to stay late with my baby boy, visiting a neighbor lady, but once someone would yell: “the English are here,” I would take my baby and start running.

But yet again, she would assure me, “that there were a few signs that would alarm us of the future intents of our Tabiyya neighbors. But why should we be scared of them, son?” She would add, “After all, we did so much to help them, and Dr. Tsemeh [a Jewish doctor who lived in Tabiyya] would come and treat our sick whenever we needed his help.”3

The name Dr. Tsemeh reoccurred in my readings about Beit Daras, and on more than one occasion. Palestinian novelist Abdullah Tayeh—himself from Beit Daras—made mention of the Jewish doctor in his historical novel, Moon In Beit Daras. A character in his novel, Abdul Aziz Mahmoud, in total despair flees the village with his family in 1948 following Tabiyya’s last successful attack on Beit Daras and the expulsion of its inhabitants; he tells himself:

What happened? How did things reach this point? Didn’t we buy and sell with the people of the kubaniya, and exchange seeds and livestock with them? And what about Dr. Tsemeh who has treated the people of the village and nearby villages, and the tibin [manure fertilizer] that I once sent him as a thank you gift, and how happy he was that day? Who was interested in destroying everything?4

Prior to the successive attacks on Beit Daras in 1948, the village was hardly defined by its relationship to Tabiyya, or by the British presence at the outskirts. The village has been in place since as far back as any of its inhabitants can remember and despite growing suspicions in the 1930s and 1940s, the villagers had little doubt that Beit Daras would remain in place for generations to come. Indeed, invading armies came and went, and none destroyed Beit Daras. It remained a witness to history’s violent and peaceful episodes, changes, progressions, defeats and victories. The place itself, its humble dwellings, might suffer or prosper, reside in anguish, or rejoice in salvation, but it had always remained largely intact as a physical entity, broken and suffering at times, true, but always standing.

Scattered in and about Beit Daras were ruins and monuments that reminded its people of unpredictable times. Beneath the village a one-kilometer-long tunnel ornately decorated with what are believed by some to be the art and script of the Canaanites was a popular destination for play by the children of Beit Daras, including my own father when he was a boy. The Crusaders (1099–1187) had left their mark; a fortified, now vulnerable and crumbling, castle on a hill that was visible from the village. The Mamluks who drove the last Crusaders out of Palestine, and defeated the Mongol hordes under Hulagu in the decisive battle of Ayn Jalut, near Nazareth in 1260, also left their mark: a small inn they erected in the center of the village to serve as a resting spot for those working on the mail route connecting Damascus to Gaza, through Beit Daras.5 Following the Ottoman conquest of Egypt in 1517, Palestine fell under the Turkish reign which ended the Mamluks’ rule over Palestine. Initially, the new rulers changed little in the way Palestine was governed under the Mamluks, save the fact that they rearranged the country’s provinces in a way that reflected their geopolitical priorities. For one reason or another, Beit Daras in 1596 was designated a village in the Gaza Province.6 But not long after the advent of the Turks, the rules of the game began changing. Now the villagers were commanded to pay heavy taxes on their crops, livestock and even beehives. The village suffered, like the rest of Palestine, as the Turks expected much and gave little in return, especially as the Ottoman Empire itself began to falter, struggling under the heavy cost of war on many fronts.

World War I created panic in the sickly empire, which for centuries had ruled most of the region of Western Asia: taxes increased at proportions that the poor villagers couldn’t match; able men were driven to war fronts that they have never heard of, fighting battles in which they had little interest. In Tayeh’s novel, Badr al-Din is a fictional Turkish commander who led a force consisting mostly of poor Palestinian peasants who were coerced to join the Turkish defenses of their falling Palestinian centers in the face of a determined British enemy. Badr al-Din thinks to himself:

The people are angry at the Turks for neglecting, impoverishing and starving them; for depriving them of all of their possessions. And now we come to force them to fight the British who came to topple our [Ottoman] Caliphate and claim its inheritance. The Turks forced these people to leave their homes, their farms, their villages, their towns, and head south, to the battlefront, to confront the British. The peasants were brought to fight a war that they know nothing of. All they were told was that they must fight until victory or martyrdom. They remained silent fearing retaliation. Villages are constantly raided [by Turkish soldiers] looking for runaway recruits. Many villagers no longer tend their fields, for they cannot afford the heavy taxes, and still pay for the seeds. Then they run away, escaping torture and prison. The peasants always ask themselves, “How can the Muslim Turks behave in such ways against their own Muslim brethren? Even the tax collectors, pray when its time for prayer, torture [the peasants] when it’s time for torture.”7

But even those dark periods were now gone, with little evidence to prove that they had ever existed. Um ‘Adel’s uncle fought in the Turkish army for twelve years, but she knew nothing of his war destinations and he seemed little interested in sharing them with the family. Like many in Beit Daras, and thousands of Palestinians, her uncle hung up his military uniform in his closet, and resumed tending the family’s farm when the war was over, as soon as Jerusalem was captured by British forces under the command of General Sir Edmund Allenby in December 1917, and the rest of the country by October 1918.

And now, Beit Daras had to put up with the British and their frightening nightly patrol while at the same time maintain an element of normalcy, as they, and their ancestors, had always done, for centuries. By 1945, Beit Daras had grown in size and population. Its inhabitants numbered 2,750, and its landholding spread to reach 16,357 dunums (a dunum is 1000 square meters, about one-quarter of an acre). While the inhabitants were living in a mere 88 dunums, the rest was land of which they had full ownership, either individually or collectively. Estimates for 1939 state that the village consisted of 401 houses.

Beit Daras had two mosques and a school that had been established in 1921 and hosted, in its first year, 234 students, in six classes, taught by five teachers. The villagers assumed the responsibility of paying the salaries of three of the teachers.8 Hundreds of villagers were literate, most astute amongst them was Grandpa Mohammed. His knowledge reached far beyond basic writing and reading. He grew to become a learned man of religion and a self-taught scholar.

THE RENEGADE

My grandfather’s quest for knowledge—relative to the cultural, economic and educational context of a small Palestinian village equipped with one elementary school in the early twentieth century—may well have been an inborn pursuit, a legacy that many of his descendants would hold onto with distinctive faithfulness. But there was certainly more to his unique inclinations in life, which set him apart from many men of his generation. His mother Qishta died when he was still an infant. Qishta’s death, for her, might have been a respite from a miserable marriage to a cruel husband, my paternal great-grandfather, Mahmoud.

Little is known about Mahmoud, save a few scattered facts to be revealed by Grandpa Mohammed over the course of many years. Each revelation would reverberate in the family, that even the grandchildren would take notice that something new has been learnt of the man of whom we hardly spoke. Indeed, Grandpa wished not speak of his father, but when he did, his eyes would fill with tears at the mere mention of that hurtful past, imposed largely, not by circumstance, but by the careless decisions of Mahmoud. A reckless man, he left his family when Mohammed was only three months old and his older daughter Dalal was ten years old. They were left without mother or father, and Mahmoud settled and married in Hamameh, a small village to the west. This was one of very few bits of information Grandpa would ever reveal.

NAME CHANGE

News of my grandfather’s life was not...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword Dr. Salman Abu Sitta

- Preface

- Map

- 1 Happier Times

- 2 Born into Turmoil

- 3 Taking Flight

- 4 A World Outside the Tent

- 5 Lost and Found

- 6 Zarefah

- 7 Al-Naksa: The Setback

- 8 An Olive Branch and a Thousand Cans of Tomato Sauce

- 9 Strange Men at the Beach Casino

- 10 Intifada: … and All Hell Broke Loose

- 11 Oslo on the Line

- 12 The World as Seen From the Stone Staircase

- 13 Dying, Again

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index