![]()

Part I

Theoretical Perspectives

![]()

1

The Neoliberal (Counter-)Revolution

Gérard Duménil and Dominique Lévy

There is a dramatic contrast between the last 20 years of the twentieth century and the previous decades since the Second World War. It is common to describe the last 20 years of capitalism as ‘neoliberalism’. Indeed, during the transition between the 1970s and 1980s, the functioning of capitalism was deeply transformed, both within countries of the centre and in the periphery. The earlier capitalist configuration is often referred to as the ‘Keynesian compromise’. Without simplifying too much, those years could be characterised, in the centre countries – the United States (and Canada), Europe and Japan – by large growth rates, sustained technological change, an increase in purchasing power and the development of a welfare system (concerning, in particular, health and retirement) and low unemployment rates. The situation deteriorated during the 1970s, as the world economy, in the wake of the decline of the profit rate, entered a ‘structural crisis’. Its main aspects were diminished growth rates, a wave of unemployment and cumulative inflation. This is when the new social order, neoliberalism, emerged, first within the countries of the centre – beginning with the United Kingdom and the United States – and then gradually exported to the periphery (see Chapters 2, 22 and 23).

We explore below the nature of neoliberalism and its balance sheet after nearly a quarter of a century. Neoliberalism is often described as the ideology of the market and private interests as opposed to state intervention. Although it is true that neoliberalism conveys an ideology and a propaganda of its own, it is fundamentally a new social order in which the power and income of the upper fractions of the ruling classes – the wealthiest persons – was re-established in the wake of a setback. We denote as ‘finance’ this upper capitalist class and the financial institutions through which its power is enforced. Although the conditions which accounted for the structural crisis were gradually superseded, most of the world economy remained plagued by slow growth and unemployment, and inequality increased tremendously. This was the cost of a successful restoration of the income and wealth of the wealthiest.1

A NEW SOCIAL ORDER

The misery of the contemporary world is too easily attributed to globalisation. One must be very careful in this respect. It is true that the two categories of phenomena, globalisation and neoliberalism, are related; but they refer to two distinct sets of mechanisms.

Globalisation, or the internationalisation of the world economy, is an old process, one that Marx identified in the middle of the nineteenth century, in the Communist Manifesto, as an inner tendency of capitalism (the establishment of a world market). The growth of international trade, the flows of capitals, and the global (at the scale of the entire globe) economy are, in no way, neoliberal innovations (see Chapter 7). The contemporary stage can, however, be characterised by growing foreign exchange transactions, the international mobility of capital, the expansion of transnational corporations, and the new role of international financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. Though the dominance of the United States is not new, neoliberalism contributed to the US hegemony within the group of other imperialist countries, in a unipolar world after the fall of the Soviet Union.

The internationalisation of capitalism has always been marked by exploitation and direct violence. This is central to imperialism (see Chapters 8 and 9). It has been at the origin of numerous wars, and destroyed lives and cultures. It drove a fraction of humanity into slavery, and generated the most extreme forms of misery throughout the planet. The world of the Keynesian compromise coexisted with colonialism and the Vietnam war. Indeed, the call for a new internationalism (the ‘other possible world’ of the anti-globalisation movement) does not express a nostalgia for the past.

In contrast, neoliberalism refers to new rules of functioning of capitalism, which affect the centre, the periphery, and the relationship between the two. Its main characteristics include: a new discipline of labour and management to the benefit of lenders and shareholders; the diminished intervention of the state concerning development and welfare; the dramatic growth of financial institutions; the implementation of new relationships between the financial and non-financial sectors, to the benefit of the former; a new legal stand in favour of mergers and acquisitions; the strengthening of central banks and the targeting of their activity toward price stability, and the new determination to drain the resources of the periphery toward the centre. Moreover, new aspects of globalisation emerged with neoliberalism, for example the unsustainable weight of the debt of the periphery and the devastations caused by the free international mobility of capitals. The major feature of the contemporary phase of neoliberalism is, however, its gradual extension to the rest of the planet, that is its own globalisation.

THE RISE OF NEOLIBERALISM: CAPITAL RESURGENCE

As is always the case when dealing with events of this nature, it is difficult to identify precisely the first emergence of neoliberalism. The same will be true of its demise or supersession. A whole set of transformations had already taken place during the 1970s, in particular internationally. ‘Monetarism’ expressed the new theoretical and policy trends. But the emblematic year is certainly 1979, when the Federal Reserve decided to suddenly increase interest rates. This is what we call the 1979 coup.

The 1970s stand out as a transition decade. In the late 1960s, the first lasting deficits in the balance of trade since the Second World War appeared in the United States. This was obviously related to the ongoing catching-up by European countries and Japan. Surpluses of dollars were accumulating in the rest of the world and, thus, the threat of conversion into gold was increasing. The dollar had to be devalued with respect to gold and other major currencies. The United States put an end to the convertibility of the dollar in 1971, introducing floating exchange rates.

In spite of the diminished comparative power of the United States in this context, the floating of currencies represented a new tool in the hands of the United States, a first component of what became, in the subsequent years, the neoliberal framework. New components were rapidly added, such as the liberalisation of capital flows, which the United States established in 1974 after the limitations of the 1960s. The United Kingdom joined the movement in 1979, and was followed by other European countries. The dynamics of neoliberalism were under way, while Keynesian policies were already under criticism.2

In the last years of his mandate, Jimmy Carter attempted to stimulate the US economy, calling in vain for international co-operation; in particular, Germany showed a growing concern with inflation and the remodelling of the international monetary system (the rising role conferred to the mark). The decision to curb inflation led to the nomination of Paul Volcker to the head of the Federal Reserve, and the ensuing surge in interest rates, up to real (corrected for inflation) rates of 6 to 8 per cent. Besides inflation, a rising wave of unemployment, in Europe and in the United States, created the conditions for a new discipline of labour, imposed by Reagan and Thatcher.

It is probably difficult to find a data series that informs more about the roots of neoliberalism than the data shown in Figure 1.1. The variable is the share of the total wealth of households in the United States, held by the richest 1 per cent. As can be seen, this 1 per cent used to hold approximately 35 per cent of total wealth prior to the 1970s. This percentage then fell to slightly more than 20 per cent in the 1970s, before rising again during the following decade (see also Piketty and Saez 2003).

Figure 1.1 Share of total wealth held by the wealthiest 1 per cent of US households (wealth includes housing, securities and cash, and durable consumption goods).

Source: Wolff (1996)

Both the causes and consequences of this movement must be addressed. The profitability of capital plunged during the 1960s and 1970s; corporations distributed dividends sparingly, and real interest rates were low, or even negative, during the 1970s. The stock market (also corrected for inflation) had collapsed during the mid 1970s, and was stagnating. It is easy to understand that, under such conditions, the income and wealth of the ruling classes was strongly affected. Seen from this angle, this could be read as a dramatic decline in inequality. Neoliberalism can be interpreted as an attempt by the wealthiest fraction of the population to stem this comparative decline.

The structural crisis of the 1970s was also a period of alleged or real decline in the domination of the United States (in the wake of the defeat in Vietnam). Japan and Germany were seen as rising stars. The risk of the assertion of a global order, organised around three centres (the triad of the United States, Europe, and Japan), was growing. This threat played a significant role in the convergence in the United States among various business and financial interests that strongly influence political parties and elections in that country (Ferguson 1995). This risk stimulated the populist component in the campaigning for the presidential election, in which national pride was invoked. Such circumstances were crucial to the election of Reagan in 1979, at the very moment finance was instigating Volcker’s action. (For finance, the rise of interest rates had three advantages: fighting inflation, raising the income and wealth of creditors,3 and using the growing indebtedness of the state as an argument to launch an attack against the welfare state.)

These events cannot be assessed independently of the failure of Keynesian policies to stimulate the economy. Keynesianism could not solve the structural crisis of the 1970s. But the neoliberal offensive against alternative models in which state intervention was strong, as in Europe and Japan and many countries of the periphery, was already under way. European ‘socialism’ rapidly conformed to the rules of neoliberalism; these included the framework of international capital mobility and the accompanying macro-policies; the privatisation of public firms and the diminished involvement in the provision of public services; and the favourable attitude towards mergers and acquisitions. However, in Europe, popular resistance conserved much of the framework of social protection. Thus emerged a hybrid social configuration, that of ‘social neoliberalism’ (see Chapters 16, 24, 25 and 29).

Although neoliberalism defines a specific power configuration, it does not preclude the continuation of long-term trends in the transformation of capitalism. The dramatic rise of financial institutions and the parallel centralisation of capital since the late nineteenth century has reached new heights since the 1980s. These financial activities and the corresponding power are concentrated within gigantic financial holdings (for example, Citigroup comprises more than 3,000 corporations located in many countries, and its total assets amounted to 400 billion dollars in 2000). They combine the traditional banking and insurance activities with new functions, for example asset management, at an unprecedented scale. In the United States, securities are gathered within a whole range of institutions, such as mutual and pension funds. All traditional ‘capitalist’ tasks are delegated to large staffs of managerial and clerical personnel. In all fields, financial or non-financial, a revolution of management is under way.

Concerning macro-policies, it is important to stress that, during the 1980s, finance did not oppose the strength of the central banks but, instead, took control of them. Monetary policy became a crucial instrument in the hands of finance, for enforcing policies favourable to its own interests. The Keynesian objective of full employment was replaced by the preservation of the income and wealth of the owners of capital, by the strict control of the general level of prices. A whole set of rules and policies is required to this end, within advanced capitalist economies. Therefore the institutions of Keynesianism were not at issue, but their objectives.

COSTS AND BENEFITS

Neoliberalism was beneficial to a few and detrimental to many. This property reveals its class foundations. This section describes some of the main features of this contrasted balance sheet, moving from the United States to Europe, to Japan and gradually toward the periphery.

WHOSE BENEFIT, WHOSE COST? A CLASS ANALYSIS

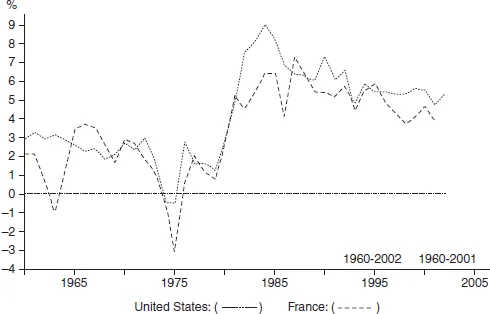

The rise of interest rates in 1979 was breathtaking and put an end to the inflationary wave. In spite of the gradual decline of nominal interest rates, high real interest rates were maintained throughout the 1980s and 1990s. This can be seen in Figure 1.2, which shows long-term interest rates in the United States and in France. Obviously, such high rates are favourable to creditors, whether individual or institutional. Moreover, high rates of dividends were also paid to shareholders. In the 1960s, the share of profits (after paying taxes and interest) distributed as dividends was approximately 30 per cent. This gradually rose to nearly 100 per cent by the end of the twentieth century. Stock-market indexes followed up, reaching their maximum in 2000.

Simultaneously, one fraction of households increased its position as creditors. In the 1960s and 1970s, in the United States, the financial assets of households amounted to approximately 100 per cent of their disposable income (that is their income after paying taxes); this reached 150 per cent during the neoliberal decades. Symmetrically, households (partly another fraction) increased their debt, from 60 per cent of their disposable income to more than 100 per cent by the end of the twentieth century. The state was also affected. Large real interest rates sharply increased budget deficits in the United States. In France, these were directly the origin of the deficits. (Neoliberal propaganda seeks to reverse the direction of causation, pinning large interest rates on deficits.)

This new course of capitalism made financial investment, and financial activities in general, more attractive. The term ‘financialisation’ has been coined to account for these new trends toward financial investment (see Chapter 11). The size of the financial sector (financial corporations) increased considerably in relation to its rising profitability. In the 1960s, still in the United States, the own funds (total assets minus debt) of financial corporations amounted to 25 per cent of that of non-financial corporations; during the structural crisis of the 1970s, this fell to 18 per cent; by 2000, it had reached nearly 30 per cent. The gradual involvement of non-financial corporations in financial activities, either directly or through affiliates, was also dramatic. Moreover, the ownership of securities was being more and more concentrated within financial institutions, such as mutual or pension funds.

Figure 1.2 Long-term real interest rates: France and the United States.

Source: OECD, Statistical Compendium 2001

One of the primary effects of neoliberalism was the restoration of the income and wealth of the upper fractions of the owners of capital, whose property is expressed in the holding of securities, such as shares, bonds or bills. This confers a financial character to their ownership. Broader segments of the population hold such securities and receive the corresponding income, in particular within their pension funds, as in the United States. Obviously—according to national and, above all, international standards – these intermediary classes enjoy a comparatively favourable situation. This is the neoliberal method of providing retirement benefits. These social groups are led to believe that they are richer, and are now part of the capitalist class. This impression was strengthened by the increase in the value of their portfolios during the second half of the 1990s, which was ephemeral. The rising wealth of those groups was an objective of neoliberalism only to the extent that it gained their support. The concentration of their assets within large funds provided a very powerful tool in the hands of finance.4 The new situation that they must, however, confront in the early twenty-first century is the threat to their ability to retire to a decent life after work.5

SLOW GROWTH, STAGNATION AND CRISIS

Neoliberalism was not responsible for the crisis of the 1970s, but the drain on incomes by finance, beginning when the structural crisis was still raging, prolonged the effects of the crisis – in particular slow growth and unemployment.

After the decline of the profit rate—within the main capitalist countries from the late 1960s to the early 1980s—which caused the structural crisis of the 1970s, new upward profitability trends occurred. The benefits of this restoration within nonfinancial corporations, however, accrued to rich households and financial institutions. Thus no restoration of profitability is apparent in a measure of the profit rate of non-financial corporations, where profits are measured after paying interest and dividends. Such a measure went on declining...