![]()

1 Class and Creative Labour

What is capital?

Capital is stored-up labour.

Marx, Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts

The more higher education becomes a qualification for specific labour processes, the more intellectual labour becomes proletarianized, in other words transformed into a commodity.

Mandel, Late Capitalism

If any one concept could be identified as absolutely central to the Marxist methodology and critique of social formations, then it would be class. Class designates a social and economic position and it always involves an antagonistic relation between classes. It is not the only cause of social division and conflict and is indeed usually complexly interwoven with other factors, from geography to other social identities such as ethnicity or gender. The nature of the relationship between class and other social relations has been the topic of much debate, controversy and argument, as well as conflicts between different political strategies. But, for Marxists, class is fundamental because of its integral links with labour and production, the very basis of social existence and development. This is an unfashionable proposition in today’s so-called ‘consumer society’, a term which conveniently conceals the human labour which makes consumption possible. If you doubt the fundamental character of labour, then just consider how much you were dependent on it in your first waking hour this morning. Assuming that you did more than stare blankly at the ceiling for 60 minutes, your morning’s dependence on labour would have begun as soon as you flicked a switch for gas and electricity; as soon as you turned a tap for water; as soon as you reached into the cupboard for your cornflakes and into the fridge for your milk; as soon as you put on the clothes you are wearing while you read this book (assuming you are wearing any). And if you did just stare at the ceiling for 60 minutes, well, someone had to make the ceiling too. All these things depend on the labour power of others, organised under particular social and economic relationships, and, while we may take these things pretty much for granted, without them, life would get brutish and short very quickly. The political and methodological implications of this (growing) social interdependence and reciprocity are nothing short of revolutionary.

The question of creative labour in cultural analysis has usually been discussed within the category of individual authorship, with the stylistic features of cultural artefacts being linked back to the key creative personnel involved in their making. There are ways of doing authorial analysis within a Marxian framework (see McArthur 2000 for example) but my concern here is with the wider social conditions of creative and intellectual labour as a collective relationship occupying a contradictory position between capital and the ‘traditional’ working class. We will need to stage an encounter between Marxist and sociological conceptions of class to explore this contradictory position, while grounding intellectual labour in some of the specific conditions of media production, such as its divisions of labour and the impact of technology.

MAPPING CLASS

Let us begin with an emblematic image – one that as a microcosm provides a map of class relations and an indication of some of the pressures and transformations within class relations in recent times. From there we can begin to crystallise the ambiguities in the class position of creative or cultural labour. The image comes from Ridley Scott’s classic science fiction/horror hybrid film, Alien (Ridley Scott 1979 GB/US), that inaugurated a remarkable series of films, which have tapped a zeitgeist around questions of the body, gender and reproduction (Penley 1989, Creed 1993, Kuhn 1990). Less remarked upon but just as central to the films and to Alien in particular is the question of class.

Conceptions of class are encoded implicitly into popular culture as a kind of common sense, an instantly, spontaneously, almost unconsciously understood code, part of our reservoir of popular wisdom and knowledge that is in general circulation. Barthes calls this knowledge, which media texts draw on and reconfigure within their specific narratives, a cultural code (Barthes 1990:20). In Alien, the crew of Nostromo, a deep space mining ship, have been awakened from suspended animation to respond to a signal from an unknown planet. In one scene, packed with signifiers of class, Parker (Yaphet Kotto, who the year before had starred in Paul Shrader’s classic working-class drama, Blue Collar (1978 US)) and Brett (Harry Dean Stanton) demonstrate their reluctance to go and investigate the mysterious signal and seek reassurances from Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) that they will be compensated for this extra work. The location for this scene is down in the bowels of the ship, the domain of Parker and Brett; despite the future setting of the action, this location is all machinery, engineering parts, pipe work and steam shooting out of valves: all classic signifiers of the industrial domain of the manual working class. The verbal discourse of Parker and Brett also signifies class location: they make it clear that they want to be remunerated for this extra work – there is clearly no sense on their part of doing something for ‘good will’. Their attitude could be said to be representative of a working-class perspective, which realistically assesses their limited career opportunities and the conflicting interests between them and their employers that make notions of ‘good will’ or ‘common benefit’ a non-starter. Ripley meanwhile clearly occupies a different class location. She has a pen and clipboard (signifying some sort of supervisory status); it is she who is answering questions rather than asking them; she quotes ‘the law’ at Parker and Brett (it apparently guarantees them their share of whatever is found): believing in the law and being knowledgeable enough about the law to quote it also indicate a different class position, in terms of education and outlook (both, as everyone intuitively knows, important indicators and determinants of precise class location). Finally, Ripley invokes the class dimensions implicit in the spatial relations of the ship (above/below) when she sarcastically tells Parker and Brett that if they want anything, she’ll be ‘on the bridge’, an explicit reference to the division of labour (and the prestige, status and power which go with that division) on the ship. Ripley, then, has all the signifiers of being middle class. These are importantly combined with the gender frisson of Ripley’s female class power over two men, and in this, as in much else, the film prophetically anticipates the influx of female labour – both middle- and working-class – which would become so marked from the 1980s onwards.

Now, what we have here, so far, is a partial map of class relations, but it is this partial map that dominates sociological discussions of class. Generally, mainstream sociology presents class as a series of layers, using occupation, income, education and consumption patterns as key criteria for defining class belonging. Mainstream sociology provides important shadings and nuances to any map of class but it characteristically excludes the really central fact of class as far as Marxism is concerned: the social (and economic) relations of production. As a result, there are huge swathes of social experience which mainstream sociology cannot address because the dominant pole in its class map, the social and economic force most responsible for the generation of change, is undertheorised and/or invisible. For example, mainstream sociological definitions of class cannot explain why in the same year that Barclays bank ran a ‘big bank for a big world’ advertising campaign, it was closing smaller branches; why developing world countries pay more money into Western banks than they do on healthcare and education; why a 0.25 per cent tax on financial speculation would raise £250 billion to tackle global poverty and why that tax is unlikely ever to be implemented; or why GM foods are being driven onto the market despite widespread consumer concern over the safety and environmental impact of the technology. Questions about the occupational or educational background of people do not begin to address how class is shaping these social phenomena. Consider this mapping of class from a popular A level sociology textbook:

Recent studies of social class have focussed on the white-collar non-manual middle class and the blue-collar manual working class. These classes are often subdivided into various levels in terms of occupational categories. A typical classification is given below.

Middle Class | Higher professional, managerial and administrative Lower professional, managerial and administrative Routine white-collar and minor supervisory |

Working Class | Skilled manual Semi-skilled manual Unskilled manual |

(Haralambos 1985:48)

Now it should be clear that the picture of class that the sociologists draw is just as much a representation of class as that found in a popular text such as Alien. Class is in this sense what Fredric Jameson calls an ideologeme, that is, a belief system which can manifest itself primarily as either a concept or doctrine (in a work of sociology for example) or as a narrative in a fictional text. While it is likely to be weighted more towards one or the other of these poles, there is always an element of both components at work since narratives cannot work without underlying abstractions and even the most conceptual work usually tells some sort of story (Jameson 1989:87). We can see that Alien draws on an ideologeme of class similar to that described in the standard sociological text, with Ripley locatable as ‘routine white-collar/minor supervisory’ and Parker and Brett as ‘skilled manual’.

However, the striking thing about the sociological map is precisely what is absent from the account. The fine grain attention which sociology pays to the differences within and between the working and middle classes is conducted via a repression of the class force which these stratas have to relate to. What is interesting about Alien (and the subsequent films in the series) is that another class force emerges, most spectacularly when one of the crew, Ash, turns out to be a robot who has been programmed by the Company to return the alien to them at the expense of the lives of the crew. This sudden and abrupt foregrounding of the Company as secretly shaping the course of events, draws our attention to that class which often disappears within mainstream sociological discussions of class: the capitalist class. To talk of the capitalist class is to stress their agency as a class; their conscious attempts to organise and shape the world according to their own interests. But capitalists are also in some sense ‘personifications of capital’ (Mészáros 1995:66) for even they must operate according to and within the parameters set by the ‘logic’ of capital. This is a structuring principle of life, which, if individual capitalists did not obey, would soon put them out of business. This logic has two main features: the drive to accumulate profit and competition. In Alien we now have a class map in which Ripley, as representative of the middle class, is dramatically relocated between the working class on the one hand and capital on the other. The figurative and conceptual blockage in mainstream sociology lies in the fact that the capital side of the sandwich which places the ‘middle class’ in the middle is unaccounted for. In Alien what Ripley and we the audience learn is that, despite her differentiation from the labour of those below her (Parker and Brett), she is viewed by the forces above her (capital) as equally expendable. And this indeed is emblematic of wider socio-structural changes. The extension and penetration of the powers of capital, particularly its restructuring of the production process, have begun to impact on wide layers of the middle class through, for example, casualisation and de-skilling. These processes cut across and come into conflict with the differentiations and privileges which capitalism also fosters.

Alien not only provides us with a more complete map of the class structure but it is important to understand that it is a map drawn from a very particular perspective: that of the middle class. For Ripley is the film’s heroine and it is in her in which it invests its hopes for overcoming the threat of the alien and the designs of the Company. One sign of this class perspective is the way the film withdraws from the tentative possibilities of a class alliance between Ripley and Parker (who will save her from Ash’s murderous designs) by killing Parker off. Thus the film may be understood as a narrative manifestation of the political unconscious of the middle class generally and specifically of the cultural workers who occupied key creative positions (principally Scott and writers Dan O’Bannon and Walter Hill) in the making of the film (Heffernan 2000:9).

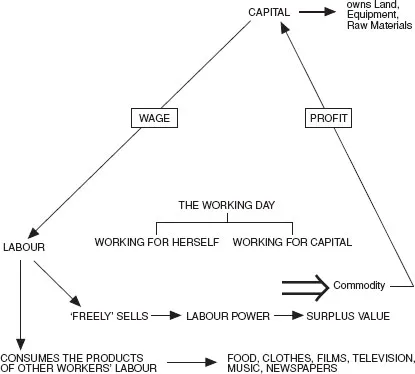

We now need to explore in more detail the Marxian conception of class as mapped out in Figure 1.1. Moving from left to right we see how labour sells its labour power to capital. Labour power, Marx writes, is ‘the aggregate of those mental and physical capabilities existing in a human being, which he [sic] exercises whenever he produces a use-value of any description’ (Marx 1983:164). Freely is in inverted commas because although there is no official compulsion to sell your labour power, unless you do or can, labour is condemned to a very impoverished and marginal existence. Thus, what Marx called ‘the dull compulsion of economics’ coerces labour, which has no other means of survival, to enter into a subordinate relationship with capital. Labour, as Marx ironically notes, is, therefore, free from, ‘unemcumbered by, any means of production of [its] own’ (Marx 1983:668). Conversely, it is the ownership of the means of production (land, equipment, raw materials) that defines capital and allows it ultimately to ‘own’ or possess for the working day the body which is inseparable from the power to labour. The diagram shows that for part of the working day the labourer is working for herself, insofar as the value, which she generates through her labour, is paid back to her in the form of wages. However, for part of the working day, labour is working free for capital since labour power has the peculiar ability to generate more value than it needs to survive and reproduce itself (clothing, eating, shelter and so on). This is called surplus value and it is this value which is embodied in the commodities which labour produces. Like an evil spirit capital then moves from the body of labour whose power to labour it activates, and into the commodity labour has produced only to then leave this material body when it is exchanged so that its use-values can be consumed; at the point of exchange, the spirit of capital flees this material body and enters into money capital which converts the surplus value (embodied in the commodity) into profit. (This analogy between the spirit of capital and ghostly spirits is developed further in Chapter 7.)

Figure 1.1 The Dichotomous Model of Class Relations

With capital replenished with profit, the personifications of capital will do two things. First, they will siphon off a part of this capital into their own personal consumption. But second – if they wish to remain personifications of capital tomorrow and the day after – they must reinvest that capital in further means of production and in wages to buy more labour power to exploit in order to recommence the whole sordid cycle all over again. Labour meanwhile takes the wages which it has earned and uses them to buy non-productive property (consumer goods) which have been produced by other workers. Some of those goods will be media commodities.

The class map tells us that the relationship between capital and labour is inherently, structurally, antagonistic. The extraction of surplus value requires capital to be the prime controller of what, where, why, when and how commodities are produced. Thus production is inherently, structurally, a site of contestation where labour deploys strategies from the small-scale to the large-scale, from the individual to the collective, which resist and subvert the priorities of capital, and capital deploys a variety of strategies to contain and stifle any challenge to its priorities and logic (Barker 1997). This contestation is called class struggle. A number of commentators who are hostile to Marxism point out that there is very little class struggle going on these days. But it all depends on what you imagine ‘struggle’ to encompass. At one end of the spectrum there are strikes and barricades in the streets, the icons of insurrection and revolution; but, on the other hand, class struggle can take quite passive and individualised forms such as absenteeism at work, or minor redistributions of wealth. Thus in A Letter to Brezhnev (Chris Bernard 1985 GB) good-time girl Theresa emerges from the factory where she spends her time with her hands up the arses of poultry, with a prime turkey specimen for her friend because it is Christmas. On the soundtrack a police siren wails in the distance. This signifier of the law asks us to ponder the meaning of Theresa’s theft compared to that larger theft of life, wealth and opportunity that constitutes her working life.

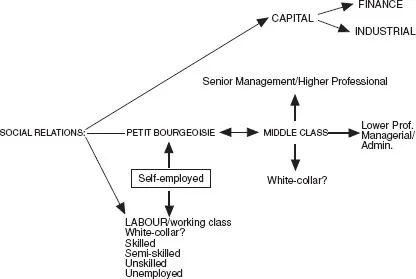

Now, it has often been objected that the dichotomous cleavage between two fundamental classes which Marxism invokes, assumes too high a degree of internal coherence and homogeneity for the two classes while at the same time failing to address the important role of the middle class. These objections need to be addressed. Let us begin with Figure 1.2. We have seen that it is commonplace for sociologists to specify differentiations within and between the middle class and the working class. Differentiations such as skilled and semiskilled within the working class and white collar and lower professional within the middle class are indeed important differentials, but sociology often sees only the differentials. Marxists would stress that such differentiations are not absolute, but different facets within the social and economic ‘unity’ of the class that sells its labour power to survive, and this includes the kinds of ‘intellectual’ labour carried out by the middle class. A classic formulation of this view of wage-labour (one which subsumes the middle class into the category of labour) was made by Marx where he argued that as labour became subordinated to capital and new technology,

Figure 1.2 Class Relations: Marxian and Sociological Perspectives Synthesised

‘the real functionary of the total labour p...