![]()

1 North Korea in context

Introduction

Why is so much attention being paid to North Korea (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea – DPRK), virtually the last state remnant of an ideological cul-de-sac that came and went in less than a century? Why is it so important not only to the neighbouring countries and the region, but also to the United States (US) and European Union (EU)? In the midst of serial nuclear crises – three to date – the Korean Peninsula is the last threat of the cold war turning hot. If the crisis on the Korean Peninsula is mishandled or miscalculated by either side, it could trigger a war. Even without the use of nuclear weapons, there would be a million dead, a trillion dollars in damage (€140 for every person in the world) and global recession. Escalation to the level of nuclear exchanges would make it, at the least, an order of magnitude worse.

The problem is a tendency to stereotype. North Korea is neither a Stalinist relic with a mad leader, nor a deadly security threat to the world. It is a country run by rational actors whose biggest concern is ‘regime survival’ and ‘regime security’ while they are still technically at war with the United States.

From a North Korean perspective, its actions are logical consequences of its struggle for survival. For those who can’t or won’t see this, North Korea becomes a dangerous enigma where the normal political levers of cause and effect have been taken away.

Northern exposure

No one should be under any illusions that North Korea and its leadership are not deeply unpleasant. Nevertheless, the country’s regime is as much a product of its enemies as of its friends and itself. It may be paranoid, but that doesn’t mean that there aren’t those out to get it.

After the end of the Pacific War, when Korea was divided by an arbitrary line drawn on a map between Soviet and American zones, both North and South wanted to fight. The South aimed for ‘national unification’ and the North for ‘national liberation’. The outcome was a civil war that turned into a surrogate conflict between the world’s two superpowers and a crusade against Communism by a United States in the throes of McCarthyism. After the end of the Korean War, North and South Korea continued to infiltrate informers, spies and terrorists across the demilitarised zone (DMZ) to undermine their alter-egos, but minus their cold-war partners they were only a threat to each other.

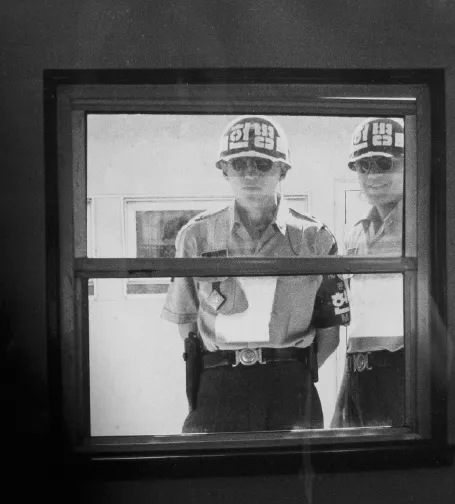

Looking in – the DMZ

North Korea had no history of democracy to fall back on and was initially constructed in the classic ‘people’s democracy’ model of the Soviet empire. It was this that directed its development in the aftermath of the Korean War. Following Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin and Stalinism in 1956, North Korea’s leader Kim Il Sung was under threat. He got his retaliation in first, purging the Party of all that opposed him or might oppose him, and ran the country with his fellow partisans, shifting the country’s focus from Stalinism to autarkic nationalism with Juche (self-reliance) as his leitmotif.

Courted concurrently by the Soviet Union and Mao’s China, North Korea’s post-war economy, based on heavy industry, initially boomed. For a period the North was a global success story. It was a desert blooming. By the late 1960s, however, the economic motor was beginning to stutter as the transposition to light industry and the production of consumer goods failed to materialise. Kim borrowed billions from the West in the early 1970s, but the turnkey projects he bought failed as the 1973 oil crisis threatened the global economy. Even at the beginning of the 1980s North Korea was the world’s 34th largest economy, but by the middle of the decade the economy had stalled. The collapse of the Soviet Union only made things worse. Aid from the Soviets stopped and from China slowed, while the Soviet nuclear umbrella over North Korea was furled. Abandoned, the North looked to develop its own nuclear deterrent, the economy went into a tailspin and the population went hungry. Kim and millions died. For Kim the cause was just biology, but the rest died as the consequence of failed policies at home and abroad, combined with floods and drought. They became nameless victims in the worst humanitarian disaster in the last quarter of the twentieth century. The United States knew of the famine, but there was no Bob Geldof or Live Aid to put their plight on the world’s TV screens. They starved slowly in a conspiracy of silence.

After a three-year hiatus Kim was succeeded by his son Kim Jong Il, who retained his father’s distrust of political reform but who was forced to recognise that his regime’s survival depended on kick-starting a stagnant economy. The only option was economic reform in the framework of a one-party state. This had been done elsewhere with varying degrees of success. China and Vietnam have taken off, while Laos and Cuba have limped. Kim’s genuine but only partially successful attempts at reform have either been ignored completely, or written off as window dressing. Some of the changes behind the scenes have been detailed by the Financial Times’ Anna Fifield. Yet while you see kiosk capitalists on the streets, Pyongyang is also encouraging the emergence of multi-sectoral conglomerates that helped Japan and the South to take off, in the former case with the Zaibatsu and the latter the Chaebol. In Pyongyang state-run shops are advertising medicines and motorbikes made by groups such as Pugang, Daesong, Sungri and Rungra 88. Jon Sung Hun, President of Pugang which has an annual turnover of $150 million (€125 million), wants to open up markets in South Korea and China. Already Pugang’s mineral water Hwangchiryong is a big seller in the latter. The United States claims Pugang is part of the Korean Ryonbong General Corporation which has been involved in nuclear proliferation. That may well have been true once in some of the corporation’s seven divisions – mining, electronics, pharmaceutical, coins, glassware, machinery and drinking water – but now its focus is on moving into the civilian economy where the money seems to be.1

South Korea is becoming nervous. Its investment is limited to the two special zones, with most new money going into the Kaesong industrial complex on the border. This has over 10,000 North Koreans working there every day, a workforce expected to rise to 300,000 by 2012. Future plans include light industry, semiconductors and bioengineering, while for fun there will be a theme park and three golf courses in the tourism zone plus an illuminated statue of Kim II Sung.2

Yet Chinese investment in the North is growing exponentially, admittedly from a very low base. It was $1 million in 2003, $50 million in 2004 and $90 million in 2005. In the past three years 150 Chinese companies have begun operating; 80 per cent of the consumer goods in the North’s markets are from China, and the $1.5 billion of bilateral trade comprises 50 per cent of the North’s total foreign trade.3 The South Korean government worries about China’s economic incorporation of the North into China’s north-eastern provinces with their large Korean-speaking minorities.

The North’s ambitions extend to the WTO, where it has expressed some interest in obtaining observer status, as post-Saddam Iraq did in 2004 and Iran in 2005 (even though in 2004 North Korea’s trade volume of $2.85 billion was 167 times smaller than South Korea’s). North Korea has been unable to get the world to take seriously its attempts to reform its domestic economy and take a Chinese-style path to market Leninism. This hidden story is brought out with the regime’s attempts at reform and engagement with the international community, all while coping with a genuine fear of US pre-emptive attack – not entirely irrational after Iraq.

Kaesong Industrial Park in July 2005

Reforms have been hampered by the ongoing political crises related to plutonium and uranium, missiles and bombs. For the United States, the 1994 Agreed Framework with North Korea that supposedly aimed to resolve the nuclear crisis was not intended to be a blueprint for a solution but to buy time for North Korea to collapse. Its promises were never intended to be delivered. The United States even reneged on its interim commitments. What Clinton did out of expediency, Bush did with joy. In a country that produces nothing anyone wishes to buy save military technology – and then only if you’re desperate – and with the rhetoric of regime change growing louder in Washington and the West, Kim Jong Il had good reasons to continue with his missile and nuclear weapons programmes.

Regime change, triggered by military intervention, as stated above would cost a million dead and a trillion dollars, making Iraq look like a minor skirmish. Meanwhile, economic collapse threatens to set 10 million refugees on the road to Seoul. A negotiated solution is needed to allow economic reform to continue and the world to feel safe from a second war on the Korean Peninsula. This will only be achieved if South Korea, China and the EU can persuade Japan and, more importantly, the United States that the interested parties in the political and military-industrial complex that seek to prolong the dispute are playing with fire. Any solution must provide North Korea with a new indigenous energy supply and development aid.

Hypocrisy and democracy

North Korea has been a ‘country of concern’ for over 50 years. Initially it was one of many within world Communism, now it is the worst of five. Since 9/11 and the ensuing ‘war on terror’. US foreign policy has taken on a hard unilateral edge. North Korea has become a part of the President’s ‘Axis of Evil’, a ‘rogue state’, and an ‘outpost of tyranny’, branded by the administration as a real and present danger to world peace. Yet it is not necessarily North Korea which poses the real problem but rather those who, for their own purposes, are determined to drive it into a corner.

Even though its last terrorist act was in the 1980s, North Korea is still classified by the United States as a state sponsor of terrorism. The Rangoon bombing in 1983, the bombing of Korean Air flight KAL 858 in 1987 and the harbouring of members of the Japanese Red Army faction have all been used to label Pyongyang a ‘terror state’. But generous double standards are at play. North Korea was a victim of airline terrorism long before the United States. Given the nod from Langley, a CIA-funded Cuban exile group blew up Cuban flight CU455 from Barbados to Cuba via Jamaica on 6 October 1976, killing five senior North Korean government officials including the Vice-Chair of North Korea’s Foreign Relations Committee. There were no survivors from the explosion and 73 people died. George Bush Senior was the Director of the CIA at the time. After he became president his son, Jeb Bush, successfully lobbied for the release of one of the two ringleaders of the plot, Orlando Bosch, who now lives unmolested in Miami. The other ringleader, Luis Posada, was under arrest in El Paso, but for entering the United States illegally. All charges were dismissed on 8 May 2007. To quote Jeb’s older brother after 9/11: ‘we’ve got to say to people who are willing to harbour a terrorist or feed a terrorist: “you are just as guilty as the terrorist.”’

Following the United States’ abandonment of the 1994 agreement, the North reactivated its Yongbyon nuclear plant, produced enough plutonium for at least half a dozen nuclear weapons, declared itself a nuclear power and conducted its first – albeit only partially successful – underground nuclear test in October 2006. This test was a ‘fizzle’ not a bang, with the assembled plutonium breaking apart too early for an optimum result. It produced a blast equivalent to 1000 tonnes of TNT or 1 kilotonne. The United States’ active nuclear arsenal has a capacity of 2330 megatonnes (1 megatonne is the equivalent of 10 million tonnes of TNT). If the North’s five remaining bombs were to operate at the 4-kilotonne design capacity, the United States would have more than eleven and a half million times the North’s nuclear power. Actually the US figure is down on what it was. In 1960 it had 100 million times what the North has today. The United States’ threat of ‘first use’ of nuclear weapons against the North during the Korean War and after was exactly what drove the Chinese nuclear programme forward in the mid-1950s. Its new doctrine of preemptive deterrence is seen in the North as an adequate reason for developing a nuclear capacity as a matter of necessity. Washington makes self-righteous pronouncements about the perils of nuclear weapons while sitting on piles of them. For the United States, one aspect of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) is vital: the aspect that stops proliferation. The other face, which promises nuclear disarmament, is just rhetoric. Moreover, North Korea’s half dozen nuclear weapons are branded a threat to both the non-proliferation regime and global security, while Israel’s hundreds and Pakistan’s and India’s scores are not.

North Korea’s arms exports destabilise global security, but the 400-times larger exports from the United States do not. North Korea’s military expenditure is a threat to South Korea, even though it spends less than a quarter of the South’s military budget. North Korea’s rapprochement with Japan is indefinitely on hold until it fully accounts for the 18 Japanese abductees to Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who in September 2006 appointed a minister to deal solely with the issue. Meanwhile Japan has yet to apologise for the almost 900,000 Koreans abducted to Japan during the Pacific War, including the tens of thousands used as sex-slaves (comfort women) by the Japanese army. The bitterness of this has not been soothed by Abe’s recent claims that they were volunteers. None of this excuses North Korea’s own bad behaviour and worse, but it provides a context. North Korea would be its own worst enemy, if it wasn’t for the United States and Japan.

Conservative forces in Japan and the United States have an agenda. One is tempted to say that if they didn’t have North Korea they would have to invent it. But in a sense that is exactly what they have done. They have dressed up as the twenty-first century’s answer to the Soviet Union at its most aggressive a deeply – and deservedly – unloved fragment of world Communism that is a failed state. They need North Korea as a scapegoat for their political projects. In Japan, the post-war generation, represented by Koizumi and now Abe, has taken over. They are self-confident nationalists who want Japan to become a ‘normal country’ by ripping up the US-imposed Peace Constitution. Public opinion polls demonstrate a majority in favour of retaining Article 9 and preventing further Japanese militarisation, so the conservatives need to transform people’s hearts and minds before the required referendum is held. North Korea is the perfect catalyst, with its ‘failed’ satellite launch over Japan on 31 August 1998 and its failed Taepodong firing on 5 July 2006, Kim Jong Il’s admission in September in 2002 that ‘rogue elements’ had abducted 13 Japanese – not the 18 that Japan claims – in the 1970s and early 1980s, and its nuclear test on 9 October 2006. Japan can fire its rockets from its launch site on Tanegashima with impunity to demonstrate its potential offensive missile technology and talk about the need to become a stronger military power when it is already the world’s fifth largest military spender, while North Korea is beyond the pale.

US attitudes are also driven by an American domestic agenda that requires an enemy in the colours North Korea is painted. Taliban terrorism and Iraqi insurgency fail to provide a motor for ‘big defence’, for military research and development. To justify the National Missile Defence (NMD) or Star Wars, ICBMs and nuclear weapons are a necessary minimum requirement, even if the numbers are hundreds of times smaller and the quality so poor that neither missile test has worked. North Korea’s efforts almost make the Star Wars tests look a success. The regional arms race, and the collapse of Communism, has driven North Korea to devote a higher and higher percentage of its shrinking income to military spending at the expense of neglecting the civilian economy. Subsequently, North Korea was driven to the nuclear option by example and economics to provide a credible deterrent. The United States forced the North Korean economy to live a lie as ‘military-first’ policies were imposed by the threat from south of the DMZ and the civilian economy starved. Yet, when Pyongyang concludes that nuclear weapons are a cheap alternative to maintaining conventional forces levels which put the economy at breaking point, it is a step too far and a threat to global security.

Regional perspectives

Views on North Korea vary amongst its neighbours depending on their own national interests. China sees North Korea as a traditional ally – even if the relationship was put under severe strain by the nuclear test – stuck in an ideological rut that ‘on the spot learning’ is beginning to shift with Kim Jong Il’s serial visits to the key monuments of China’s economic miracle. Russia, or rather the Soviet Union, saw the North as an unruly ally. Towards the end, economics leapfrogged over history and Seoul took precedence over Pyongyang. More recently Russia has seen that totally sidelining the North meant it missed political and industrial opportunities. Now while Seoul is the centre of its focus on the peninsula, enough interest is maintained in the North to ensure Moscow does not miss out again. Japan, unwilling to acknowledge its contribution to the burden of the past and the shaping of the present, sees a vengeful North obsessed with a deliberately distorted vision of Japanese colonialism. The North’s failure to come clean on the abductions of Japanese citizens makes bad relations worse. Pyongyang provides an excuse for Japanese politicians to manipulate the Japanese population. South Korea views the prospect of early forced re-unification with horror, preferring a ‘soft’ to a ‘hard’ landing, but ideally no landing at all. Historically North and South have been Siamese twins with a love–hate relationship. Each needs the other to measure itself against, to test itself, to justify its existence. You can’t have one without the other. US fundamentalist approaches that are willing to force regime chang...