eBook - ePub

The Orders of the Dreamed

George Nelson on Cree and Northern Ojibwa Religion and Myth, 1823

- 238 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Orders of the Dreamed

George Nelson on Cree and Northern Ojibwa Religion and Myth, 1823

About this book

The introduction by Brown and Brightman describes Nelson's career in the fur trade and explains the influences affecting his perception and understanding of Native religions. They also provide a comparative summary of Subarctic Algonquian religion, with emphasis on the beliefs and practices described by Nelson. Stan Cuthand, a Cree Anglican minister, author, and language instructor, who lived in Lac la Ronge in the 1940s, adds a commentary relating Nelson's writing to his own knowledge of Cree religion in Saskatchewan. Emma LaRoque, an author and instructor in Native Studies, presents a Native scholar's perspective on the ethics of publishing historical documents.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Orders of the Dreamed by Jennifer S.H. Brown, Robert Brightman, Jennifer S.H. Brown,Robert Brightman, Jennifer S. H. Brown, Robert Brightman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

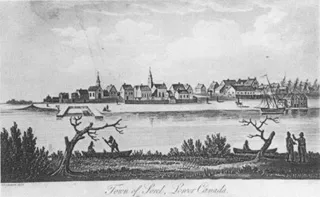

In the fall of 1807, John Lambert visited William Henry (Sorel) where the Nelson family lived. Although he found the town attractive with several stores and two churches, it did not appear prosperous. Many local men were voyageurs in the Northwest, leaving the cultivation of their farms to their wives and children (Travels through Canada and the United States of North America, in the Years 1806, 1807, & 1808, 2 vols., London 1816). Illustration from vol. 1, pp. 506-07, courtesy of the Newberry Library, Chicago.

Overleaf: NbNc-1, Hiekson-Maribelli Site 2 Face xiv

INTRODUCTION

GEORGE NELSON

Background, Career, and Writings

Among Anglo-Canadian fur traders of the early nineteenth century, George Nelson stands out for his interest in the life and ways of the natives he encountered. His writings testify to his willingness to listen seriously and with a relatively open mind to what his Ojibwa and Cree associates had to tell him, and to his attention to detail and eagerness for accuracy. As a fur trade clerk, he served the XY Company (Sir Alexander Mackenzie and Company) from 1802 to 1804, the North West Company from 1804 to 1816 and again from 1818 to 1821, and the Hudson’s Bay Company from 1821 (the time of its merger with the North West Company) until 1823. Yet while attending to business in an evidently competent manner, he also became a good observer and recorder of both the native and non-native people around him. His manuscripts are an invaluable and scarcely tapped resource on all the parties involved in the fur trade social sphere - and particularly on the Indians.

Nelson’s papers are comprised of two major groups of materials: the manuscripts written during his fur trade service, and a body of reminiscences written between 1825 and about 1851, from two to twenty-eight or more years after he left the northwest. The document published here, which belongs to the first group, is, like the great majority of known Nelson material, held by the Metropolitan Public Library of Toronto, Canada.

In form, it is an untitled letter-journal, sixty foolscap pages in length, addressed to George Nelson’s father, William. Internal dates and statements show that it was composed at intervals between March and early June 1823, while Nelson was serving as Hudson’s Bay Company clerk in charge of Lac la Ronge (northeastern Saskatchewan), an outpost of Ile à la Crosse. The Lac la Ronge letter-journal is the last of his texts written in the Indian country, and the only substantial surviving manuscript concerning the final of his nineteen years of fur trade life.

Only one of Nelson’s writings has previously appeared in print - his post-retirement reminiscence of his 1802-03 winter in the St. Croix River valley in northwestern Wisconsin (Bardon and Nute 1947). Some of the other papers bearing on the fur trade are being prepared for publication by Sylvia Van Kirk. The Lac la Ronge text includes relatively little about the fur trade, however, and because it stands apart as an ethnological contribution of high quality and great interest, we decided to annotate and publish it separately. This introduction portrays its author’s background and career, and some of the contexts of his writing and thought. The text itself is reproduced in Part II. Part III, “Northern Algonquian Religious and Mythic Themes and Personages,” places the document in a broad historical and ethnological perspective. In Part IV Stan Cuthand offers a personal commentary on Nelson’s text, reflecting upon his own Cree heritage and his life in two worlds, and Emma LaRocque presents a native scholar’s perspective on publishing historical documents.

Family and Childhood

Nelson spent his early years first in Montreal and then in a Loyalist community in Sorel, Lower Canada (now Quebec), about fifty miles down the St. Lawrence River from Montreal. His parents, William, a schoolmaster originally from South Shields, County Durham, England, and Jane Dies, were married in Sorel (or William Henry as it was then known) on 24 May 1785 (Nelson Family Papers 1765; Couillard-Despres 1926, 141; Christ Church (Anglican) Registers 1787). Both had been among the many New York Loyalists who came to the Sorel area to escape the American Revolution. George, their eldest child, was born on 4 June 1786. He was followed by at least eight other children. The only two who found fame in their lifetimes were Wolfred and Robert, conspicuous for their roles in the Rebellion of 1837 in Lower Canada (Thompson 1976; Chabot, Monet, and Roby 1972).

George received, and evidently absorbed with success, a sound basic education; both the Lac la Ronge text and his other writings demonstrate considerable literacy and some familiarity with classical mythology and European intellectual currents. But on 13 March 1802, his father and the local notary set him upon a new course, drawing up a five-year contract to engage him in the fur trade as an apprentice clerk with the XY Company (Sir Alexander Mackenzie and Company), the firm which from the late 1790s to 1804 so vigorously challenged the North West Company for the fur trade beyond the Great Lakes (Archives nationales du Quebec 1802). There were probably two reasons that William Nelson allowed George to take up this career at so early an age. First, George himself, infected by the examples of many other local youths who took up this adventurous life for what seemed a liberal salary, “was seized with the delirium” of their enthusiasm and campaigned to go (Bardon and Nute 1947, 5-6). Second, the fact that George as the eldest son had by that time six younger brothers and sisters in need of support may have swayed his father’s views.

The Wisconsin Years

On 3 May 1802, George left Lachine, the fur traders’ departure point near Montreal, in a brigade of six canoes to travel to the depot of Grand Portage on the southwestern shore of Lake Superior; then on 13 September he left there with three men to winter in northern Wisconsin (Bardon and Nute 1947, 6, 144). Nothing in his previous experience except hearsay from returned traders had prepared him for life in the fur trade and among the Indians, and he poignantly recorded his early homesickness and the trials of adjusting to so foreign a setting. Yet he remained open to contact with and involvement in his new world, gaining the Indians’ acceptance and support, and even a tie of kinship. As he later recalled, “a mere stripling - how they laughed at, and pitied me alternately. A lad about a year older than myself, took a fancy for me, and treated me as a friend indeed: his father was well pleased, and adopted me in his family” (Brown 1984; see also Bardon and Nute 1947, 150).

In 1803, after a summer visit to Grand Portage, Nelson returned inland in mid-August, to winter in the Lac du Flambeau and Chippewa River areas of northern Wisconsin. Much travelling was necessary during this difficult winter, partly to avoid encounters with hostile Sioux, and partly because of food shortages. While under these stresses, Nelson had three

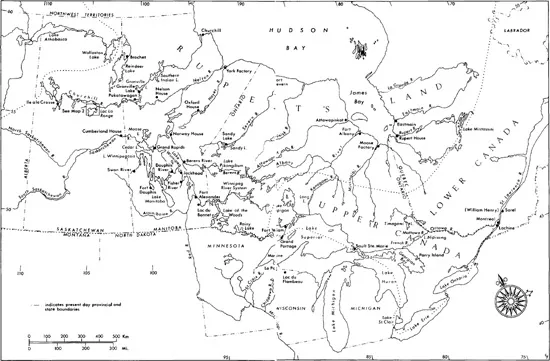

Map 1. Regions and places known to George Nelson or mentioned in Part III. (Map by Caroline Trottier)

memorable experiences with Wisconsin Chippewa variants of the Northern Algonquian practice of conjuring as a means of seeking information and securing game, although use of the shaking tent, which he later found so common in more northerly areas, was absent in these instances. It is interesting that on all three occasions, Nelson and his men fostered or even initiated these activities, in empathy, it seems, with the Indians’ sense that conjuring was, in the circumstances, as good and useful a coping strategy as any, and more satisfying than most.

The first incident was in early January 1804. Nelson became anxious when some of his men who were coming from another post did not arrive. His reminiscences record frankly, but with some introductory hesitancy, his successful application to a conjuror on this occasion:

I don’t know whether I should relate a circumstance of conjuring that I had done by an old indian at this house. I had sent two men to our house above for rum. They had been gone 7 days beyond the time they thought they would be, and 3 days beyond what I expected. I therefore employed this old man, who, report said, never failed speaking truth, His way was after every body had retired to rest - he would have no Spectators. How he done I know not, probably it was inspiration, or vision in his dreams; but the indians said his familiars appeared to him, or told him, what he wanted to know. The next morning he told the people: “The men will be here by noon - they slept last night at such a place. They have had a great deal of trouble - they were near drowning, and are very hungry. But they are well, and bring the rum!” All he said turned out to be so correct that those who had been up, thought he had followed them (1825ff., 48).

By early February, both traders and Indians were in great need of food. The conjuring efforts that followed are described both in the Lac la Ronge letter-journal printed here and in Nelson’s reminiscences. The latter (1825ff., 49-50) contain some vivid details that complement the account penned at Lac la Ronge:

Our indians frequently conjured, i.e., prayed and sang, and laid out all their most powerful nostrums, to kill bears, all to no purpose. How many appeals, what beating of drums, singing, smoking, &c, &c. Still to no purpose. At As last Le Bougon, or Chubby, he who had killed the indian in the autumn, who was with us, said he would try. “I should succeed, I know, because I have never yet failed; but I have polluted myself [by killing] and I have no hope! What an event! How wretched am I now!” He was at last prevailed upon. “Well!” said he, “I will, possibly on your account, who have had nothing to do in that melancholly affair, I may possibly be heard!” At dark, he began, laying out and exposing all his nostrums, roots, herbs and dolls, to Pray (harangue), sing, beat his immense large drum, and smoke. He kept close to it the whole night. At Sun rise he gave a cry to attract attention, and accosted the others. “Old man,” naming Le Commis [ an Indian], “you will find a large Bear, after much trouble, in that wind fall, on the opposite Side of this creek. You, young man,” to the Commis’ Son, “you will follow your father’s track till you have passed the two Small Lakes - you will see a Fir tree thrown down by the wind, beyond that is another windfallen tree, by the root of which you will find a young one, his first year alone. I also have one up this river!” And, if I remember right, he gave one to Le Commis’ elder brother, who was with us. This is so strange, and so out of the way that I will ask no one to believe it. Those who will not believe the Gospel will still less credit this; yet I say it is true, believe who may. We had a Splendid feast at night, for they were very fat.

The third conjuring session was conducted by the traders themselves later that winter, after further food shortages for which Nelson, in retrospect, felt himself culpable, in his youth and inexperience: “we were still so improvident, and myself so thoughtless that we were literally always starving.” Only partly in jest, Nelson and his men decided one hungry day “to imitate the indians’ conjuring":

We speechified, sang, beat the drum, smoked and danced; Sorel, he who sang the best, imitating them, would run to the chimney yelling, “something shall be cooked in that place” - part indian, part french and English - “tomorrow, tomorrow, at latest, I smell it.” The next day Le Commis brought us the sides of a moose he had killed! Sorel was frequently called upon after this, but he had lost his influence (1825ff, 51).

Nelson’s second Wisconsin year, aside from these hardships and events, was also taken up by his involvement in an intimate native connection formed in the fall of 1803. His old Ojibwa guide, Le Commis (mentioned above), who was to lead Nelson to his wintering quarters, evidently hoped for an enduring trade and kinship tie with the young clerk, and presented him with his “very nice young daughter” whom he wished him to marry. Nelson put him off, citing the strictures of both his father and his employers, Sir Alexander Mackenzie and the XY Company, against such premature involvements. He later recorded the sequel: “The old fellow became restless and impatient: frequently menaced to leave me, and at last did go off. I sent out my Interpreter to procure me another guide. In vain - my provisions being very scanty, my men so long retarded, fear of not reaching my destination; and, above all the secret satisfaction I felt in being compelled (what an agreable word when it accords with our desires) to marry for my safety, made me post off for the old man… . I think I still see the satisfaction, the pleasure the poor old man felt. He gave me his daughter!” (1825ff., 35-36).

While Nelson clearly took pleasure in accepting the girl, the bond with her father had special importance. Indeed, as the conjuring incidents quoted earlier help to show, he found several times that winter that “our subsistence … depended entirely upon what the old man and his friends whom he kept with him, could procure us.” But Nelson also became genuinely fond of Le Commis: “He was good, harmless, faithful, and his temper was so good that one could never discover when he was hurt but by a dejection of countenance and spirit, which yet soon gave way” (1825ff., 36, 40).

The summer of 1804 saw the end of that familial tie, however. On Nelson’s return to Grand Portage, he was censured for his behavior and was obliged to send the girl away, a duty which he accomplished rather clumsily (Brown 1984). His posting to the Winnipeg district that season removed him permanently from the Wisconsin region.

The Wisconsin years made an indelible impression on Nelson’s mind. He was at that time between the ages of sixteen and eighteen, sensitive and quick to learn. His progress toward eventual fluency in the Ojibwa language certainly began in this period. In remote inland settings where white companions were few and not necessarily congenial, and where Indian attentions and support were essential to his trade, Nelson found that his Indian ties were of great practical and personal value. Having an observant and inquiring disposition, he began also to learn about Ojibwa ways, which he found understandable and well suited to the conditions of northern life.

The Lake Winnipeg Period

The Lake Winnipeg phase of Nelson’s career put him on familiar terms with the “Sauteux” (Saulteaux) or Northern Ojibwa of that area (cf. Steinbring 1981), and later acquainted him with the more northerly “Mashkiegons” (usually described by later writers as Swampy Cree) as they began to seek out the North West Company’s trade. (On variants of terms for these Indians of the York Factory area and inland, see Pentland in Honigmann 1981,227; Bishop 1981, 159.) No journal survives for the 1804-05 season spent at the mouth of the Red River, or for 1806-07; and that for 1805-06, spent at Lac du Bonnet on the Winnipeg River, is incomplete. Reminiscences written in the 1830s, however, help to fill the gaps, recounting, for example, local traders’ reactions to the news of the merger of the XY and North West Companies in November 1804, following the death of Simon McTavish.

The 1805-06 journal, running from late August to early March, gives a good overview of seasonal activities and interactions with Ojibwa of the Lac du Bonnet area. Nelson once again became a kinsman of the Indians; his reminiscences note that, some time before November 1805, “The Red Breast [known in the journal as Red Stomach], a very good and sensible man, had adopted me as his Son.” On various occasions, Nelson visited both Red Breast and his brother ("uncle” to the young trader) in their lodges (Brown 1984). In all, thirteen Indians and their families were named at one time or another as having trade ties with Lac du Bonnet in 1805-06.

When Nelson moved to the western Lake Winnipeg area in the fall of 1807, he became a part of increasing North West Company efforts in that area. By 1805-06 six NWC posts ringed the Lake Winnipeg basin: at Cross Lake to the north, Pike (Head) River (also known as Jack Head or Tete au Brochet) on the west shore, and Lake Folle Avoine (Rice Lake), Pigeon River, and Broken River on the east side, all subordinate to Bas de la Riviere (Fort Alexander) at the mouth of the Winnipeg River (Nelson 1805-06, 3 Jan. 1806; Lytwyn 1986, fig. 20). Nelson’s new post lay just west and north of Jack Head, on the “River Dauphine” (Dauphin River), the waterway to the Fort Dauphin area and the outlet for Lake St. Martin and other lakes to the southwest.

Nelson’s voyage to this place was marked by near disaster, and by the founding of a new and valued Indian tie. On 13 September 1807, while encamped at Tete au Chien (Dog Head), Lake Winnipeg, he was severely burned by the explosion of a keg of gunpowder. Immediate immersion in cold water and subsequent treatments with native remedies made from swamp tea and larch pine (tamarack) aided his recovery, as did the advice of Ayagon, the local Ojibwa leader in whose area Nelson was to be stationed. Ayagon urged Nelson to take a purgative to help remove the smoke particles and poisons from his system, and impressed the young clerk at the time by his “sound rational remarks” (1825ff., 194).

As a man of some seniority and influence both among his countrymen and in the fur trade, Ayagon became an important figure during Nelson’s years on the west side of Lake Winnipeg. Although sometimes difficult to deal with, he became another adoptive father (see, for example, Nelson’s River Dauphine journal, 2 August 1810) and a friend. Nelson appreciated in him the distinctive qualities of northern Algonquian leadership patterns: “He would only speak when there was occasion, but always to the purpose and expressed his ideas with ease and fluency; and when he had occasion to use his authority, which, by the bye, was very limited out of his fam...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Part I

- Part II

- Part III

- Part IV

- References

- Index

- Footnote