![]()

CHAPTER 1

Reconstructing Indigenous Masculine Thought

Bob Antone

This is a story of a search for Indigenous knowledge that constructs masculinity within a reflective process; an examining of my personal journey to dismantle the Westernized male acculturation influencing the contemporary construct of being a Haudenosaunee man.

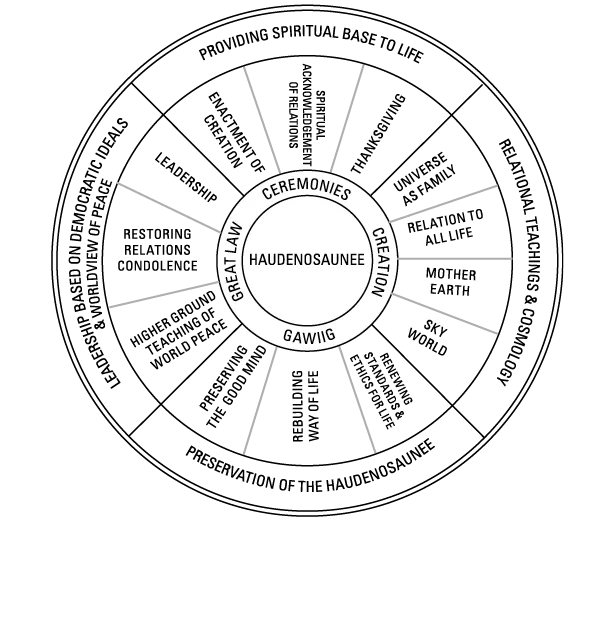

This homecoming is a journey of sourcing original thought. For this reason, I open this chapter by introducing core elements of Haudenosaunee knowledge/original thought, as represented in Figure 1.1. This figure references the Haudenosaunee Creation story, the Ceremonies, the Great Law, and the Gaiwiio. These cultural sources form the Ukwehu:we (literally, Real Human Being or Iroquois) masculine mindset.

As Indigenous people, our reality began long before 1492, and so we begin by seeking understanding of our Creation stories. One cannot be Indigenous or contemplate Indigenous masculinities without the original knowledge of Creation informing and supporting one’s spirit and thought. Haudenosaunee knowledge is permeated with a theological world view rooted in a pragmatic spirituality of dream, storytelling, relationship, morality, dependency, thankfulness, and operating with a Good Mind.

Ceremony is another significant component toward centring our identity through Haudenosaunee knowledge. Today, culture is acted out in ceremonies in the longhouse1 and continues to be the foundation of who we are as Haudenosaunee. The many ceremonies are celebrations of life, Haudenosaunee attachment to the traditional foods, and enacting the creation of Mother Earth. Learning ceremony places the Ukwehu:we in a different spiritual place than Western constructs of spirituality.

Figure 1.1. Haudenosaunee Knowledge.

The Great Law of Peace is the third source of Haudenosaunee knowledge that came to the people through a messenger we call the Peacemaker. The importance of the Great Law is its contribution to Haudenosaunee identity and spiritual purpose. The message came to the Ukwehu:we over a thousand years ago and has been the defining teachings of being the Haudenosaunee. When the teachings originally came to the people, it was during a time when violence was rampant among them. The teachings of peace, power, and the Good Mind address the issue of violence within the community.

A fourth foundation of our knowledge dates back to 1799, when our people received a message from a Seneca visionary named Handsome Lake. Through the power of dream, visions came to this reluctant soul, an ordinary man who had lost most of what he loved to the invading forces. By 1799, the force of the colonization had turned our communities into oppressive, violent, addicted environments, which were the products of war, colonization, genocide, and the cruelty of the oppressors. Handsome Lake addressed the state of our nations by sharing his vision of a need to stay away from the “mind changers” of the white man, which included their alcohol, laws, Bible, diseases, and music. The message was to keep the four sacred ceremonies going, follow the teachings of the Good Mind, ensure the raising of chiefs and clan mothers, and adjust the way one lived to keep life simple and meaningful. The Gaiwiio, Handsome Lake’s message, set in motion a process for the decolonization of Haudenosaunee communities. For the last 214 years, this effort has grown among us.

Handsome Lake advocated for the continuance of the Great Law, the original teachings of non-violence. The Western illusion of discovery and dominance of other cultures is in direct conflict with the traditional constructs of peace and non-violence. The other significant cultural difference is the all-encompassing matrifocal or women-centred foundation of Haudenosaunee culture rooted in the constructs of Mother Earth, Grandmother Moon, Three Sisters’ foods, and clan mothers who select the leadership and identity based on who your mother is. As Ukwehu:we men, our psyche has to accept those teachings if we are going to decolonize.

Recently, I spoke at the Great Law Recital held in my community, Oneida Settlement. The presentation labelled the experiences of our ancestors and our own life experiences as colonization, and our recovery as decolonization. We were naming our reality; a thought process that originates in the depth of our collective Haudenosaunee mind. This chapter documents my journey from my time as a young man to that Great Law Recital of 2013, as a facilitator of decolonization work and as a Haudenosaunee man unravelling and shedding the colonial cloak of Western masculinity through the application of the knowledge represented in Figure 1.1.

Historical Background

Understanding how history contributes to masculine identity is vital to uncovering the decolonized Indigenous man, and so I also offer my history by way of introduction. My history is about a homeland in upstate New York, the relocation to southern Ontario of 391 Oneidas, and the creation of a new community in Southwold, Ontario, which we call Oneida Settlement. In 1844, four years after the migration, the British government reported that “there were…6 frame and 48 log homes with 4 wigwams…and a total of 335 acres under cultivation.”2 The people busied themselves with re-establishing a community.

In March of 1850, the Oneidas sent a delegation to the Six Nations at Grand River to request that the chiefs come and condole and raise new chiefs to form a new Oneida Settlement government. The British Indian agent Clench attended the meeting at Grand River and observed “the ancient ceremony of burying the hatchet between the Six Nations and the Oneidas who had shed each other’s blood at the instigation of the British and American Governments.”3 The act of reconciliation is a natural Haudenosaunee process; it is not one bound in sympathy but in finding Ka?nikohli:yo, a communal Good Mind shared in the equal and joyful presence of one another. The Good Mind is one of the founding principles of the Great Law and the traditional customs that continue to inform the roles of men and women and the relationships between them.

Oneida people remained attached to their homelands 150 years after a migration that did not severe their ties to the United States. The Oneida went on with rebuilding their nation, exiled in the Beaver Hunting Grounds.4 The community was thus governed by the Chiefs’ Council until the Canadian colonial imposition of the Indian Act Band Council system in 1934. For ninety-six years, the community enjoyed the exclusive extension of the traditional form of government from their homelands. Traditional forms of government continued to inform the men on how leadership, respect, communal relations, peace, and the Good Mind principle structured and organized the community. The Chiefs’ Council continues holding regular meetings today.

In spite of our ability to hold onto the Chiefs’ Council, by the late 1960s, the elders, chiefs, and clan mothers publicly announced the dire situation of cultural loss. Young Oneidas acknowledged the call and returned to the longhouse to help with the recovery. It was this call that caught my attention, and I returned home to help. In 1969, I was around when a group of Oneidas from Wisconsin began their cultural recovery process. A relationship grew between the Wisconsin and Ontario Oneida communities, both spiritual and personal in nature, commencing a new chapter in the Oneida cultural recovery.

The Oneida Chiefs’ Council, with the assistance of younger men, began to travel regularly to every Grand Council at Onondaga and the Six Nations meeting at Grand River, picking up the responsibilities of leadership and carrying the voice of the Oneida Nation Council. The young men, like me at the time, accompanied the chiefs to learn.

The 1970s was a very volatile time in Indian Country, providing Indigenous men with opportunities to organize, demonstrate, voice their anger, and refuse to be shackled by the settler governments. Groups of Oneida men and women travelled to the various events from Wounded Knee, South Dakota; Washington, DC; Ottawa, Ontario; and First Nations communities across Canada and the U.S. to demonstrate, participate, and learn about the struggle of all Indigenous peoples.

In 1982, a condolence ceremonial known as the Raising of Chiefs and Clan Mothers was held in the Oneida Settlement, advancing the construction of an original government. To increase the connection with our relatives in Wisconsin, Faith Keepers were selected and appointed with the sanction of the central fire of the Oneida Nation at Southwold. Faith Keepers, chiefs, and clan mothers travelled to Wisconsin to officiate over the ceremonial proceeding at a mid-winter ceremony. More men were taking on long-forgotten responsibilities.

The significance of this work was acknowledged with the placing of an official “fire” at the longhouse in Wisconsin in 2004, the first in the twenty-first century. This was a culmination of forty-four years of cultural revitalization work by many Oneidas from different communities with the assistance of the Haudenosaunee, the longhouses of the other nations. Language programs are now offered in all three communities despite differences in other areas, such as land claims and politics. Oneidas continue to journey between communities, building relationships and learning together. These efforts create new roles for men as teachers while renewing their ancient roles as orators.

The Iroquoian linguist and ethnographer J.N.B. Hewitt explored our culture and religion through the language, identifying “Kalenna” as the “mystic potency”5 or “spiritual bundle”6 that each person is born with. All Iroquois have an innate spiritualism, cultivated for generations, increasing the desire for their own identity. The soul or spirit of the Ukwehu:we man is charged with a duty inherently attached to Haudenosaunee teachings. Perhaps as a result of this spirit, the forces of assimilation and acculturation pressuring Oneidas to change and be white, Christian, tax paying, landless, uncultured, marginalized, second-class citizens, and followers of the band council system did not prevail. The power of the Kalenna (spiritual bundle), Ka?nikohli:yo (the Good Mind), and the flexibility of the culture and teachings absorbed the cultural shock and helped us to resist.

Among the Oneida communities, the Oneida Settlement7 maintains the cultural practices more successfully. We are a more closed, isolated society, which has helped us to resist the assimilation efforts of the settler society. Even though most Euro-American and Canadian writers/researchers predicted that the culture would end, our recent history has proven that their ethnocentric view was wrong. Yet political, social, and cultural experiences of the last thirty-five to forty years demonstrate that Ukwehu:we men in general need to continue to work to retain and regain the mental, emotional, and spiritual space for the following principles:

• Oneida women are the critical identity holders of the nation.

• The women continue to pass on the inner desire to be Oneida and to be a part of something larger, the Haudenosaunee.

• Proximity to the rest of the Haudenosaunee is a critical factor in the sharing of culture.

• Marriage between communities and nations helps to maintain the Haudenosaunee identity.

• The relationship between Six Nations of the Grand River and the Oneida Settlement increases the viability of the traditional forms of belief through ceremonial, constitutional, governmental, and traditional clan roles.

• The ceremonial system of reconciliation settles disputes and historic disagreements to rejoin the original order of peace, friendship, and the Good Mind.

This is a part of my history that I have been deeply involved in for over forty years. It is this history that informs my spiritual and political masculine thought.

Putting Knowledge into Practice: Initiating Men’s Healing

My adult life began with the realization that our culture was under threat, as the Elders feared that no one wanted to learn. My life direction has taken me on a path involved in community organizing and social service work, seeking ways to restrengthen culture and wellness, ways to combat racism, and ways to secure sovereignty and self-determination. As the son of a father who was sentenced to ten years in a residential school, I realized early on that I carry the scars of multi-generational genocidal Canadian programs and I sought a greater understanding of the role of men in Indigenous society. I could see that the heart and spirit of men had fallen victim to colonialism and internalized oppression. I wanted to explore what Indigenous men needed to challenge the internalized oppressive behaviours of men.

During the same time that Indigenous political activism was happening, Indian Country was witnessing the birth of a new home for the cultures in the healing continuum that had emerged. This movement was led by women, inspiring us to ask the questions, Where were the men? What was preventing them from accessing this phenomenon of healing?

Part of the answer could be found in the historical record, which showed how colonialism continues to influence the path of Indigenou...