- 126 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

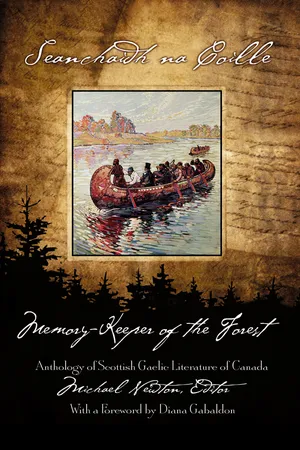

Seanchaidh na Coille / Memory-Keeper of the Forest

About this book

From Vancouver to Cape Breton, Scottish Gaelic-speaking communities could be found all over Canada from the late-18th to the mid-20th century. This is the first anthology of prose and poetry – mostly literary, some historical in tone – to give voice to the experience of Gaelic Canadians. It covers a wide range of territory and time, allowing Gaels to express their own opinions about a broad set of themes: migration, politics, religion, family life, identity, social organizations and more.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Seanchaidh na Coille / Memory-Keeper of the Forest by Michael Newton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Geografia storica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

StoriaSubtopic

Geografia storica1 – Introduction

A Multitude of Solitudes

Since the 19th century, the standard means of celebrating the legacy of Scottish immigrants and their descendants in both Canada and the United States has been to compile and embellish a list of influential people of Scottish descent widely known because of their political power, financial success, entrepreneurism or artistic accomplishments. It is not hard to find numerous examples of people who meet these criteria: catalogues always include such luminaries as Sir John A. Macdonald, Sir Alexander Mackenzie (explorer of the Pacific northwest), Hugh MacLennan (novelist) and so on.

There are a number of problems and shortcomings with this formulaic approach, however. The importance and prominence of the mainstream Scottish “heroes” is generally determined by their ability to work within the confines and standards set by anglophone society. The recognition of their success is ultimately a celebration of anglophone culture rather than the culture in which they themselves or their ancestors originated.

Even the notion of Scottishness needs further refinement to be meaningful. Like Canada, Scotland consists of at least two solitudes, one of which is rooted in the Highlands and Western Isles, speaks Gaelic and has a long history of conflict with the anglophone world, including the Scottish Lowlands. This segment of the Scottish population invested as much as any other in the formation of Canada: recent research has revealed that Scottish Gaelic was the third-most spoken European language at the time of Confederation.1 And yet today, apart from scattered homesteads in Nova Scotia, not only has the language receded from the immigrant communities that once spoke it, but it has practically disappeared from public memory. The descendants of Gaels, who once described themselves as bitter enemies of English speakers, are now categorized as “English Canadians” with only occasional nods to the many distinctions that once divided them.2

The linguistic limitations of scholars have often confined the materials used to tell these stories to sources written in English. These constraints coincide with the willingness of many Gaels and their descendants in North America to reduce their ancestral culture to the set of colourful symbols in favour with the dominant culture—tartans, kilts, bagpipes, etc.—and to abandon the rest. Yet, there are ample sources available in their native language, Gaelic, to construct much more complex narratives that do not concur so neatly with Anglocentric triumphalism, tales that occupy the marginal spaces shared by other subaltern peoples. If we examine the materials produced by Gaelic immigrant communities, we can find a different set of heroes and accomplishments that are more relevant from their own cultural perspectives. The texts in this volume may help restore some balance to the list of who has been celebrated and who has been ignored and forgotten in the conventional Scottish-Canadian “Hall of Fame.”

Although some of the memories preserved in this volume could be described as heroic or celebratory, some are not. Canadians of Scottish descent, who do not want to challenge the status quo, or question their position and privilege within it, may not wish to embrace all of these memories. They are crucial, nonetheless, if we are to understand the story of Scottish Gaelic immigrants in its fullness and complexity. The reconstruction of historical experiences is always complicated by the selective process of highlighting the aspects that meet the approval of contemporary opinion and purging the elements that are less seemly or favourable.

The stories of how and why Scottish Gaels came to Canada and what happened after they arrived has been obscured not only because of the shortage of trained scholars who can read and interpret the sources, but also because the immigrants themselves and their descendants have sometimes suppressed or altered elements that proved awkward or embarrassing to retain in public view. Rusty Bitterman has noted, for example, that while the first generation of immigrants denounced the disenfranchisement and poverty that they endured in Scotland, these radical critiques could be easily repressed once the immigrants were drawn into the forces of commercialism and could prosper from it, whatever its negative impact on other peoples.

Although members of the upper echelons of Highland society helped to construct an anti-commercial critique of the agrarian transformation of the Highlands and to transfer it to the New World, they and their descendants would over time distance themselves from key aspects of this construction. Having arrived in a new environment and assayed some of the possibilities of the New World, many, like Murdo MacLeod, must have found certain aspects of their past inconvenient and dispensable.3

Immigrant Gaels in Canada found themselves enmeshed in systems willing to harness their energies to advance the Anglocentric agendas of the British Empire, but resistant to any notion of the inherent value of cultures and languages, and the identities expressed by them, that did not align with imperial priorities and pretensions. By assimilating to dominant identities of “Britishness” and “whiteness,” when they were available, Gaels could gain access to the highest levels of privilege and power in Canadian society, but at the cost of trivializing and distancing themselves from their ancestral inheritance.4

Many popular books about the legacy of Scottish immigrants in Canada treat Scotland as if it were a homogenous country populated by people whose differences in customs, language, social structure, and religion were of little consequence, if worth discussing at all. This is a convenient fiction that disregards one of the most fundamental facts of Scottish history, that of the division between Highlands and Lowlands. This partition, and the social processes that caused and perpetuated it, conditioned both sets of people for the experiences they were to have in Canada and informed their perceptions of themselves and others. While relations and exchanges between Highlands and Lowlands were complex and in constant flux, the general trends and emergent attitudes leading up to the 18th and 19th centuries are clear enough.

To Lowlanders, the Highlands5 were a wild place populated by uncouth and uncivilized people who spoke a detested alien language. Being lazy and treacherous by nature, they preferred to steal and plunder rather than produce wealth through their own effort and industriousness. Lacking civility and refinement, they obeyed no laws of morality or political principle but were inveterate rebels against authority and rationality. The use of ideas from classical texts depicting the opposition between civilization and savagery suggest that Lowlanders were anxious about the implications of growing linguistic, religious and political ties between themselves and England while the unconquered Gaelic “barbarians” defied demands for assimilation and the presumed “laws of progress.”6

The native inhabitants of the Highlands and Western Isles, for their part, saw the people of the Lowlands as incomers and interlopers who usurped the fertile plains as well as the royal court, disenfranchising Gaels from the independence and prestige that they had once enjoyed as the founders of the Scottish nation.7

Anne Grant of Lagan (in the Central Highlands), a woman who spent parts of her life in British North America, Lowland Scotland and Highland Scotland during the late 18th and early 19th centuries and who spoke both Gaelic and English, relates to us that antipathy and distrust were mutual:

No two nations ever were more distinct or differed more completely from each other, than the Highlanders and Lowlanders; and the sentiments with which they regarded each other, was at best a kind of smothered animosity. ...

The Highlanders, again, regarded the Lowlanders as a very inferior mongrel race of intruders, sons of little men, without heroism, without ancestry, or genius ... who could neither sleep upon the snow, compose extempore songs, recite long tales of wonder or of woe, or live without bread and without shelter for weeks together, following the chace. Whatever was mean or effeminate, whatever was dull, slow, mechanical, or torpid, was in the Highlands imputed to the Lowlanders, and exemplified by allusions to them...8

These animosities were carried forward into Canada just as much as any common sense of “Scottishness,” especially when Highland immigrants did not conform to the ethnolinguistic norms and expectations of anglophones. In a survey of Gaelic traditions in Prince Edward Island conducted in 1987, for example, John Shaw remarked, “A small portion of PEI Scots had come from the Scottish Lowlands and according to reports they demonstrated naked hostility to Gaelic—more so than any other ethnic group.”9

Such prejudices have characterized fraught relationships between many different ethnic groups, but negative stereotypes about Highlanders have proven particularly resistant to deconstruction. With the collaboration of Lowland Scotland in the British Empire and the triumph of an Anglocentric master narrative, derogatory caricatures of Gaels are still often taken at face value.

Many Scottish Canadians did not want to challenge or offend what appeared to be the unassailable dominance of the anglophone ascendency: they only wished to ingratiate themselves with it and be included within its bounds. Pleas for respectability and acceptance called for highlighting the cultural practices and features held in common with anglophones and suppressing or silencing the rest. Take, for example, a speech delivered at the St. Andrew’s Day celebration on November 30, 1857 to the St. Andrew’s Society of Montreal:

In these things we seek besides to illustrate and adorn the common brotherhood which knits us to those of our own land, kindred and tongue. It cannot be said of Scotchmen that they have ever been indifferent to the wants or the sorrows of their countrymen. None of us, I believe, can hear the Doric familiar language of our native home, speaking the words of distress or telling the tale of suffering, without feeling the liveliest sympathy with the sufferer. ...

Since the time of the Reformation, Scotland has not simply been a Nation represented by a king and government, but it ha...

Table of contents

- Copyright Notice

- Seanchaidh na Coille | The Memory-Keeper of the Forest

- Epigraph

- Praise for Seanchaidh na CoilleThe Memory-Keeper of The Forest

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- 1 – Introduction

- 2 – The Subjugation of Gaeldom

- 3 – Militarism and Tartanism

- 4 – Migration

- 5 – Settlement

- 6 – Love and Death

- 7 – Religion

- 8 – Language and Literature

- 9 – Identity and Associations

- 10 – Politics

- Conclusions

- Biographies

- Maps

- Notes

- References

- Index

- Other Celtic/Gaelic Titles from CBU Press

- About Michael Newton