![]()

Part 1.

Jung’s Early Work

Jung began his career in psychiatry in December 1900, when he was appointed as an assistant physician at the Burghölzli mental hospital in Zurich. Breuer and Freud had published their Studies on Hysteria in 1895; and Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams had appeared in November 1899. But psychiatrists were still fascinated by the researches of Janet and Morton Prince into cases of “multiple personality,” and it was this phenomenon which inspired Jung’s first published work: his dissertation for his medical degree, “On the Psychology and Pathology of So-called Occult Phenomena.” This was based on his observations during seances of a 15½-year-old cousin, Hélène Preiswerk (called S. W. in the paper), who was reputedly a medium. She claimed to be controlled by a variety of spirits, varying from her grandfather, who was deeply serious, to a figure called Ulrich von Gerbenstein, who was flirtatious and frivolous. Jung interpreted these various figures as “unconscious personalities.”

From “On the Psychology and Pathology of So-called Occult Phenomena” CW 1, par. 77

In our account of S. W.’s case, the following condition was indicated by the term “semi-somnambulism”: For some time before and after the actual somnambulistic attack the patient found herself in a state whose most salient feature can best be described as “preoccupation”. She lent only half an ear to the conversation around her, answered absent-mindedly, frequently lost herself in all manner of hallucinations; her face was solemn, her look ecstatic, visionary, ardent. Closer observation revealed a far-reaching alteration of her entire character. She was now grave, dignified; when she spoke, the theme was always an extremely serious one. In this state she could talk so seriously, so forcefully and convincingly, that one almost had to ask oneself: Is this really a girl of 15½? One had the impression that a mature woman was being acted with considerable dramatic talent.

Janet conducted the following conversation with the subconscious of Lucie, who, meanwhile, was engaged in conversation with another observer:

[Janet asks:] Do you hear me? [Lucie answers, in automatic writing:] No.

But one has to hear in order to answer. – Absolutely.

Then how do you do it?-I don’t know.

There must be someone who hears me. – Yes.

Who is it? – Somebody besides Lucie.

All right. Somebody else. Shall we give the other person a name? – No.

Yes, it will be more convenient. – All right. Adrienne.

Well, Adrienne, do you hear me? – Yes.

One can see from these extracts how the unconscious personality builds itself up: it owes its existence simply to suggestive questions which strike an answering chord in the medium’s own disposition. This disposition can be explained by the disaggregation of psychic complexes, and the feeling of strangeness evoked by these automatisms assists the process as soon as conscious attention is directed to the automatic act. Binet remarks on this experiment of Janet’s: “Nevertheless it should be carefully noted that if the personality of ‘Adrienne’ could be created, it was because the suggestion encountered a psychological possibility; in other words, disaggregated phenomena were existing there apart from the normal consciousness of the subject.”* The individualization of the subconscious is always a great step forward and has enormous suggestive influence on further development of the automatisms. The formation of unconscious personalities in our case must also be regarded in this light.

As we have seen, the various personalities are grouped round two types, the grandfather and Ulrich von Gerbenstein. The grandfather produces nothing but sanctimonious twaddle and edifying moral precepts. Ulrich von Gerbenstein is simply a silly schoolgirl, with nothing masculine about him except his name. We must here add, from the anamnesis, that the patient was confirmed at the age of fifteen by a very pietistic clergyman, and that even at home she had to listen to moral sermons. The grandfather represents this side of her past, Gerbenstein the other half; hence the curious contrast. So here we have, personified, the chief characters of the past: here the compulsorily educated bigot, there the boisterousness of a lively girl of fifteen who often goes too far. The patient herself is a peculiar mixture of both; sometimes timid, shy, excessively reserved, at other times boisterous to the point of indecency. She is often painfully conscious of these contrasts. This gives us the key to the origin of the two subconscious personalities. The patient is obviously seeking a middle way between two extremes; she endeavours to repress them and strives for a more ideal state. These strivings lead to the adolescent dream of the ideal Ivenes, beside whom the unrefined aspects of her character fade into the background. They are not lost; but as repressed thoughts, analogous to the idea of Ivenes, they begin to lead an independent existence as autonomous personalities.

This behaviour calls to mind Freud’s dream investigations, which disclose the independent growth of repressed thoughts.

From “School Years” MDR, pp. 44–6/33–4

Around this time I was invited to spend the holidays with friends of the family who had a house on Lake Lucerne. To my delight the house was situated right on the lake, and there was a boat-house and a rowing boat. My host allowed his son and me to use the boat, although we were sternly warned not to be reckless. Unfortunately I also knew how to steer a Waidling (a boat of the gondola type) – that is to say, standing. At home we had such a punt, in which we had tried out every imaginable trick. The first thing I did, therefore, was to take my stand on the stern seat and with one oar push off into the lake. That was too much for the anxious master of the house. He whistled us back and gave me a first-class dressing-down. I was thoroughly crestfallen but had to admit that I had done exactly what he had said not to, and that his lecture was quite justified. At the same time I was seized with rage that this fat, ignorant boor should dare to insult ME. This ME was not only grown up, but important, an authority, a person with office and dignity, an old man, an object of respect and awe. Yet the contrast with reality was so grotesque that in the midst of my fury I suddenly stopped myself, for the question rose to my lips: “Who in the world are you, anyway? You are reacting as though you were the devil only knows how important! And yet you know he is perfectly right. You are barely twelve years old, a schoolboy, and he is a father and a rich, powerful man besides, who owns two houses and several splendid horses.”

Then, to my intense confusion, it occurred to me that I was actually two different persons. One of them was the schoolboy who could not grasp algebra and was far from sure of himself; the other was important, a high authority, a man not to be trifled with, as powerful and influential as this manufacturer. This “Other” was an old man who lived in the eighteenth century, wore buckled shoes and a white wig and went driving in a fly with high, concave rear wheels between which the box was suspended on springs and leather straps.

This notion sprang from a curious experience I had had. When we were living in Klein-Hüningen an ancient green carriage from the Black Forest drove past our house one day. It was truly an antique, looking exactly as if it had come straight out of the eighteenth century. When I saw it, I felt with great excitement: “That’s it! Sure enough, that comes from my times.” It was as though I had recognized it because it was the same type as the one I had driven in myself. Then came a curious sentiment écoeurant, as though someone had stolen something from me, or as though I had been cheated – cheated out of my beloved past. The carriage was a relic of those times! I cannot describe what was happening in me or what it was that affected me so strongly: a longing, a nostalgia, or a recognition that kept saying “Yes, that’s how it was! Yes, that’s how it was!”

From “Tavistock Lecture II” CW 18, pars. 97–106

First of all I want to say something about word-association tests. To many of you perhaps these seem old-fashioned, but since they are still being used I have to refer to them. I use this test now not with patients but with criminal cases.

The experiment is made – I am repeating well-known things – with a list of say a hundred words. You instruct the test person to react with the first word that comes into his mind as quickly as possible after having heard and understood the stimulus word. When you have made sure that the test person has understood what you mean you start the experiment. You mark the time of each reaction with a stop-watch. When you have finished the hundred words you do another experiment. You repeat the stimulus words and the test person has to reproduce his former answers. In certain places his memory fails and reproduction becomes uncertain or faulty. These mistakes are important.

Originally the experiment was not meant for its present application at all; it was intended to be used for the study of mental association. That was of course a most Utopian idea. One can study nothing of the sort by such primitive means. But you can study something else when the experiment fails, when people make mistakes. You ask a simple word that a child can answer, and a highly intelligent person cannot reply. Why? That word has hit on what I call a complex, a conglomeration of psychic contents characterized by a peculiar or perhaps painful feeling-tone, something that is usually hidden from sight. It is as though a projectile struck through the thick layer of the persona into the dark layer. For instance, somebody with a money complex will be hit when you say: “To buy,” “to pay,” or “money.” That is a disturbance of reaction.

We have about twelve or more categories of disturbance and I will mention a few of them so that you will get an idea of their practical value. The prolongation of the reaction time is of the greatest practical importance. You decide whether the reaction time is too long by taking the average mean of the reaction times of the test person. Other characteristic disturbances are: reaction with more than one word, against the instructions; mistakes in reproduction of the word; reaction expressed by facial expression, laughing, movement of the hands or feet or body, coughing, stammering, and such things; insufficient reactions like “yes” or “no”; not reacting to the real meaning of the stimulus word; habitual use of the same words; use of foreign languages – of which there is not a great danger in England, though with us it is a great nuisance; defective reproduction, when memory begins to fail in the reproduction experiment; total lack of reaction.

All these reactions are beyond the control of the will. If you submit to the experiment you are done for, and if you do not submit to it you are done for too, because one knows why you are unwilling to do so. If you put it to a criminal he can refuse, and that is fatal because one knows why he refuses. If he gives in he hangs himself. In Zurich I am called in by the Court when they have a difficult case; I am the last straw.

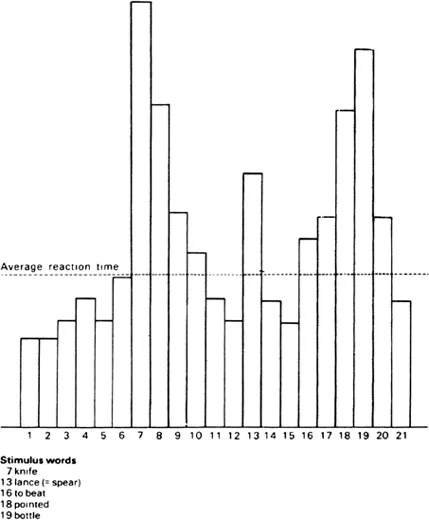

The results of the association test can be illustrated very neatly by a diagram (Figure 5). The height of the columns represents the actual reaction time of the test person. The dotted horizontal line represents the average mean of reaction times. The unshaded columns are those reactions which show no signs of disturbance. The shaded columns show disturbed reactions. In reactions 7, 8, 9, 10, you observe for instance a whole series of disturbances: the stimulus word at 7 was a critical one, and without the test person noticing it at all three subsequent reaction times are overlong on account of the perseveration of the reaction to the stimulus word. The test person was quite unconscious of the fact that he had an emotion. Reaction 13 shows an isolated disturbance, and in 16–20 the result is again a whole series of disturbances. The strongest disturbances are in reactions 18 and 19. In this particular case we have to do with a so-called intensification of sensitiveness through the sensitizing effect of an unconscious emotion: when a critical stimulus word has aroused a perseverating emotional reaction, and when the next critical stimulus word happens to occur within the range of that perseveration, then it is apt to produce a greater effect than it would have been expected to produce if it had occurred in a series of indifferent associations. This is called the sensitizing effect of a perseverating emotion.

Figure 5. Association Test

In dealing with criminal cases we can make use of the sensitizing effect, and then we arrange the critical stimulus words in such a way that they occur more or less within the presumable range of perseveration. This can be done in order to increase the effect of critical stimulus words. With a suspected culprit as a test person, the critical stimulus words are words which have a direct bearing upon the crime.

The test person for Figure 5 was a man about 35, a decent individual, one of my normal test persons. I had of course to experiment with a great number of normal people before I could draw conclusions from pathological material. If you want to know what it was that disturbed this man, you simply have to read the words that caused the disturbances and fit them together. Then you get a nice story. I will tell you exactly what it was.

To begin with, it was the word knife that caused four disturbed reactions. The next disturbance was lance (or spear) and then to beat, then the word pointed and then bottle. That was in a short series of fifty stimulus words, which was enough for me to tell the man point-blank what the matter was. So I said: “I did not know you had had such a disagreeable experience.” He stared at me and said: “I do not know what you are talking about.” I said: “You know you were drunk and had a disagreeable affair with sticking your knife into somebody.” He said: “How do you know?” Then he confessed the whole thing. He came of a respectable family, simple but quite nice people. He had been abroad and one day got into a drunken quarrel, drew a knife and stuck it into somebody, and got a year in prison. That is a great secret which he does not mention because it would cast a shadow on his life. Nobody in his town or surroundings knows anything about it and I am the only one who by chance stumbled upon it. In my seminar in Zurich I also make these experiments. Those who want to confess are of course welcome to. However, I always ask them to bring some material of a person they know and I do not know, and I show them how to read the story of that individual. It is quite interesting work; sometimes one makes remarkable discoveries.

I will give you other instances. Many years ago, when I was quite a young doctor, an old professor of criminology asked me about the experiment and said he did not believe in it. I said: “No, Professor? You can try it whenever you like.” He invited me to his house and I began. After ten words he got tired and said: “What can you make of it? Nothing has come of it.” I told him he could not expect a result with ten or twelve words; he ought to have a hundred and then we could see something. He said: “Can you do something with these words?” I said: “Little enough, but I can tell you something. Quite recently you have had worries about money, you have too little of it. You are afraid of dying of heart disease. You must have studied in France, where you had a love affair, and it has come back to your mind, as often, when one has thoughts of dying, old sweet memories come back from the womb of time.” He said: “How do you know?” Any child could have seen it! He was a man of 72 and he had associated heart with pain – fear that he would die of heart failure. He associated death with to die – a natural reaction – and with money he associated too little, a very usual reaction. Then things became rather startling to me. To pay, after a long reaction time, he said La Semeuse, though our conversation was in German. That is the famous figure on the French coin. Now why on earth should this old man say La Semeuse? When he came to the word kiss there was a long reaction time and there was a light in his eyes and he said: Beautiful. Then of course I had the story. He would never have used French if it had not been associated with a particular feeling, and so we must think why he used it. Had he had losses with t...