![]()

PART I

On Britons, Saxons and Vikings (650–1066)

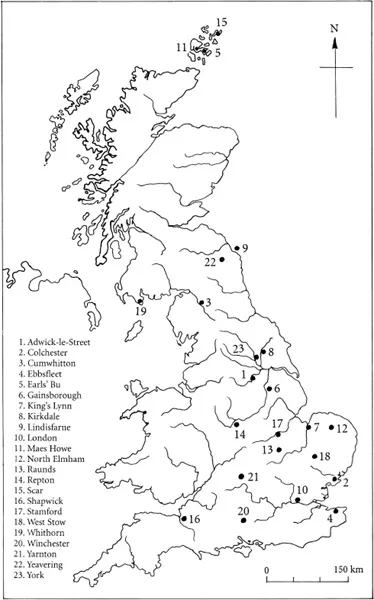

FIG 1 Principal places mentioned in Part I.

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The North/South Divide of the Middle Saxon Period

THIS CHAPTER will mainly be about the emergence of England. First, however, I must say a few words about the state of the countryside in general in the three centuries or so after the departure of the last Roman troops in AD 410, the generally accepted date for the end of the Roman presence in Britain. To summarise briefly, in the years prior to about 1960 it was believed that the British countryside reverted to a state of near wilderness when everything collapsed after the Roman withdrawal. The term often used to describe the situation was a ‘waste’ or ‘wasteland’, in which forests covered the land and the sun was excluded from the ground. Then waves of new settlers from across the North Sea arrived in Britain, felled the forests and pushed the few inadequate natives west towards Wales. The new people brought with them an entirely new way of life.

In Britain AD I discussed how archaeology and environmental science have shown that there was in fact very little forest regeneration, and that if anything the post-Roman landscape became more open, and the styles of farming more diverse. All the evidence points to continuity in the landscape: there was no wholesale disruption, such as one might expect if the entire population of what was shortly to become south and east England had in fact changed. Most towns and cities were indeed abandoned, but this was a process that had begun long before, in a remarkably sudden and coordinated fashion shortly after AD 300 – a full century prior to the Roman departure. The distinguished scholar of Roman Britain Richard Reece has suggested that this was because towns in Roman Britain were an idea ahead of their time, and that their grip on the population was at best tenuous – and soon slipped. Whatever the explanation, and I find Reece very convincing, Romano-British town life effectively ceased in the early fourth century and there was a (consequent?) rise in rural prosperity, which included the construction or enlargement of many elaborate country houses, known to everyone today as Roman villas.

To the north and far west the British population at large was less affected by the Roman presence, and many aspects of Iron Age life continued right through to post-Roman times. This is not to say that rural settlements here were grubby hovels, because the pre-Roman inhabitants of these areas had developed their own ways of living in what was sometimes quite a wet and windy environment. As we will see when we look at life in the Bernician royal centre at Yeavering in Northumberland, these people were perfectly capable of achieving a remarkably sophisticated style of life.

Plague may have played a role in keeping the population of Britain down in Early Saxon times. Bede mentions it on several occasions with reference to the seventh century.1 The problem I have with this is that the seventh century was a time when town life in Britain was pretty much non-existent, and it was in the crowded towns of the fourteenth century that the Black Death reaped its most devastating harvest. It affected rural areas too, but not as much. As we will see when we come to discuss that particular outbreak, plague tends to recur again and again, and it seems odd to me that it should die out at more or less the precise time that towns, in the form of the Middle Saxon wics, begin to come into their own.

It is also worth noting that the impact of the Black Death in 1348 was so devastating that the southern British population could not have retained any vestiges of immunity from earlier infections. In other words they must have been completely free from it – and for several generations. It seems to me that the plagues Bede writes about are unlikely to have wiped out whole swathes of the British population, thereby releasing land for huge numbers of people from across the North Sea to settle on. It is, however, entirely possible that plague in the seventh century could have played a role in freeing the survivors from restrictive ties and obligations.2 Just as we will see in the four-teenth century, the greater availability of land ultimately led to prosperity – which was such a feature of southern Britain in the Middle Saxon period.

For these and other reasons I suggested in Britain AD that the Anglo-Saxon invasion was more a spread of ideas than of actual people, as there is no convincing archaeological evidence for war cemeteries or for David Starkey’s ‘ethnic cleansing’. In a few decades I feel sure that genetics will be able to sort the problem out, one way or another. If it is indeed found that wholesale population replacement did take place, the challenge to archaeologists will be to work out how this could have happened. What was the social mechanism that enabled such a huge ethnic transformation to occur without, it would seem, major social disruption and conflict?

Maybe we can learn something here from the story of the Vikings, who were successful invaders, but who also seemed hell-bent not so much on rape and pillage (which certainly happened) but on settling down and becoming English peasant farmers. The Viking army, however, left clear and unambiguous documentary and archaeological evidence for warfare – something which is still lacking in the archaeological record of the Dark Ages. Perhaps some other, more subtle and archaeologically undetectable, process was at work in Early Saxon times. Maybe strict new codes of marriage introduced by the arriving Anglo-Saxons prevented native British women from having children; maybe too there was some other form of eugenic apartheid. As yet we simply don’t know, but one day we might find out. Either way, it will require some creative thought.

In Britain AD I also discussed the events that led up to the Synod of Whitby (AD 664), at which it was decided that the future of England lay with the Roman rather than the Celtic Church. From a very long-term perspective this was a most important decision, because it ensured that thenceforward British intellectual and spiritual attention would be directed towards Europe. The medieval period was also a time when the authority of the Church played a central role in most aspects of the life of the nation. Before Whitby the Church was altogether more fragmented, and its growth more organic. After Whitby it became both more centralising and more institutional, and soon became a significant power in the land. The increasing importance of the Church also promoted literacy and gave rise to a greater and more widespread use of written documents.

By the early seventh century the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of what was later to be England were beginning to emerge, and we know of a series of very rich or ‘royal’ burials at places such as Sutton Hoo, Taplow and Prittlewell. I described these graves in Britain AD, and I will not repeat myself here, other than to say that these lavish finds show that society was clearly becoming increasingly hierarchical, and that powerful ruling elites had begun to emerge.3 By the end of the Early Saxon period Christianity was of growing importance, as is well illustrated at Prittlewell (AD 650), where an otherwise pagan chamber burial, with roots that can be traced back to the pre-Roman Iron Age, had been ‘Christianised’ by the addition of two gold foil crosses.

The documentary evidence for Middle Saxon England is much better than that for Early Saxon times. Among the sources available to us, two stand out. The first has to be the work of that great genius of northern Britain, the Venerable Bede, who wrote his Ecclesiastical History of the English People in 731. But there is also a most remarkable eleventh-century source, a tax assessment known as the Tribal Hidage. This document gives us an important glimpse into the earliest geography of England, and I will consider it further in Chapter 3, when we come to discuss the development of administrative units such as the shires.

I mentioned Brian Hope-Taylor in my Introduction. His remarkable excavations at Yeavering in Northumberland transformed our knowledge of Earlier Saxon high-status architecture. His work has given us a vivid picture of life within a royal household in northern Britain prior to the onset of Viking raids. Strictly speaking, Yeavering was in use in the decades just before 650, the notional start of the Middle Saxon period, but dates such as these are for convenience only – and it is convenient for me to ignore them now. First I want briefly to discuss life in Britain north of, say, Yorkshire. Then we will turn our attention further south. The contrast between the two regions will help explain the phenomenon that has come to be known as the Vikings.

It is strange how certain bits and pieces of what you learned at school or university stay with you in later life. Sometimes these half-remembered fragments are of little consequence: does it really matter, for example, that one could have walked across the North Sea 12,000 years ago? Although I was quite interested in the archaeology of early medieval Britain, I never really got to grips with what was happening in the north of the island, except to marvel over the illuminated pages of that superb masterpiece in the British Museum, the Lindisfarne Gospels. This came to the museum in 1753 as part of its ‘Foundation collections’, which also included the only copy of that remarkable Anglo-Saxon epic poem, Beowulf..4

Before Brian Hope-Taylor’s excavations and the great growth in Scottish and northern archaeology that has happened since, the main sources of information on early medieval Britain were carved stone crosses, inscriptions, and of course those superb illuminated manuscripts. Their rich decoration owed much to various influences from within Britain, and the style has come to be known as the ‘insular tradition’. Here the term ‘insular’ is not meant to be pejorative; it simply signifies that the manuscripts produced on the island of Britain were quite distinct from those being produced elsewhere in Europe. They were also just as good as, or even better than, anything on the Continent. Besides the Lindisfarne Gospels there are two other famous examples, the Books of Durrow and of Kells (both in the Library of Trinity College, Dublin).5 All three are Gospels and are particularly renowned for their intricate ‘carpet pages’ of elaborate interlaced design whose vivid 3-D effects would actually make them lethal if woven into floor coverings. The spirit behind the restless movement of this work recalls, for me at least, the unquiet world of pre-Roman, so-called ‘Celtic’ Art. There is little here of the Roman Church, or indeed of Roman culture.

The suggestion of ‘Celtic’ influences summons up images of Ireland, but one should not be misled into thinking that the insular tradition was about Ireland, or those Irish settlers in Scotland, the Scotti, alone. English, or rather Anglo-Saxon, influences were also very important contributors to this rather heady graphic cocktail. We saw in Britain AD how there is growing evidence for mobility in Anglo-Saxon England, and the same can be said for the lands around the western seaways.6 The art of the insular tradition is clearly a fusion of both English (Anglo-Saxon) and British traditions, but its great flowering was sometime after the Synod of Whitby. The Book of Durrow and the Lindisfarne Gospels are probably mid-seventh century, and Kells is slightly later (late eighth). It may have been the stability provided by the new post-Whitby political and ecclesiastical regime that provided the environment for the new style to emerge and flower. One is tempted to reflect that it is far easier to alter the outward form of religious rituals than the feelings and emotions that lie behind them.

At college we learned in some detail about the glories of these three great works. I also remember seeing the Book of Kells as a small boy when I was taken by one of my Irish uncles, Esmonde, to the library of Trinity College, Dublin, where he himself had been a student. Esmonde was to become a historian of Hitler’s pre-war policy at London University, but at that stage his life in Dublin was rather wild and included some very colourful friends, like the playwright Brendan Behan. Esmonde taught me by example that the past was far too important to be taken too seriously. In the drab days of the 1950s those huge, colourful pages, glinting with gold, made a lasting impression on me. The Book of Kells features large animals, strange beasts and the huge-eyed faces of biblical characters such as the Gospel writers. It has always been among my favourite works of art.7

One might suppose that such great art was produced in a well-endowed culture where people had the time and resources to lavish upon such things. Indeed, that was how life in northern Britain was seen when I first learned about the Celtic Church. Brian Hope-Taylor’s excavations at Yeavering, if anything, reinforced this view of a heroic age that could still find the time to encourage the contemplative life of men such as Bede, or the masters who created the great illuminated manuscripts. That term ‘heroic age’ says it all. But what does it really mean?

The best answer I have come across has been provided by the greatest scholar of northern Britain in early medieval times, Professor Leslie Alcock, who has just published a magisterial review of his subject.8 Alcock makes it clear that this was indeed a heroic age in which great feats of valour on the battlefield were celebrated in verse and song; but there was more to it than just fighting. Many sources refer to scenes from the life of Christ, and it is apparent that the essentially pagan ideals of the heroic age were transferred to Christian beliefs. The ideals of a warrior elite were tempered by the humanity of those who, like Bede, opted for the quieter life of the soul.

The political situation in what is now northern England in the seventh – ninth centuries was extremely unstable. This is remarkable, because the eighth century saw what has been called a Northumbrian Renaissance, epitomised by scholars such as Bede and religious houses such as Lindisfarne. To the north and east, occupying the land in England and Scotland around the Cheviot Hills, was the kingdom of Bernicia, with Deira to the south, centred around the fertile Vale of York. Deira was taken over by Bernicia in the mid-seventh century, and both were then subsumed within the large kingdom of Northumbria, whose borders fluctuated quite widely, especially when campaigns against its northern neighbours took a turn for the worse. Southwestern Scotland was occupied by the Scots (or Scotti in Latin), who were in fact settlers from Ireland. North of the Firth of Tay were the Picts. During the heroic age much of the warfare took place between Angles from Bernicia and the Picts or the Scots further north.

Yeavering is about as far north in what is now England as it is possible to go. It is located in the Cheviot Hills, at the heart of Bernicia, just below a prehistoric hillfort known as Yeavering Bell. If you struggle over the ramparts of this hillfort in late winter, when the rough grass is low, you can clearly see the circular outline of collapsed Iron Age roundhouses. The settlement is on gently sloping ground at the foot of Yeavering Bell, whose commanding presence is everywhere, and which must have been the principal reason why the site was selected as a royal centre. The inhabitants of Yeavering could claim descent and protection from the ancestral figures who constructed the great hillfort.

This Bernician royal settlement – and I use that loaded word advisedly – went through a number of different phases. Great timber halls appear, are modified and replaced. Cemeteries even grow, come and go. But throughout its development the site shows the clearest signs of organisation and thought. Alignments matter, and symbolism is significant. Sometimes as I ...