eBook - ePub

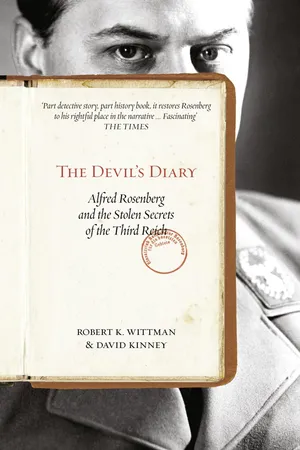

The Devil's Diary

Alfred Rosenberg and the Stolen Secrets of the Third Reich

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Devil's Diary

Alfred Rosenberg and the Stolen Secrets of the Third Reich

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Devil's Diary by Robert K Wittman, David Kinney in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

AT WAR

1939–1946

14

“The Burden of What’s to Come”

He did not see it coming. Alfred Rosenberg heard the earth-shattering news on the radio at the same moment as everyone else in Germany, just before midnight on August 21, 1939: His beloved Führer was making peace with Rosenberg’s most hated enemy, the Soviet Union. Hitler was dispatching a delegation led by Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop to Moscow to finalize a nonaggression pact.

Just the idea of it—the odious Ribbentrop hoisting glasses of vodka in the Kremlin with Joseph Stalin—was too much for Rosenberg to stomach.

No one in the Third Reich could possibly have been more shattered to hear of the pact than Rosenberg. Twenty years he had spent sounding the alarm about communists and their “Jewish criminality.” It had been his life’s work. It was and would always be the centerpiece of his entire political worldview. Now what was he supposed to do? Swallow hard and fall in line?

Surely this was not the Hitler of Mein Kampf, who had written that living space for the Germans could only come at the cost of the Soviet Union and its territories, and who had ridiculed the idea of an alliance with the Bolsheviks. “Never forget that the rulers of present-day Russia are common bloodstained criminals; that they are the scum of humanity which, favored by circumstances, overran a great state in a tragic hour.” Surely this was not the man who had issued this dire warning: “The fight against Jewish world Bolshevization requires a clear attitude toward Soviet Russia. You cannot drive out the Devil with Beelzebub.” Surely this was not the Führer who had told Rosenberg, a few short years back, that the Nazis could never find common cause with the Soviet Union, that nest of bandits, “because it wasn’t possible to forbid the German people from stealing, and to simultaneously remain friends with thieves.”

By sending Ribbentrop to cut a deal with Moscow, the Nazis were suffering “a moral loss of face in light of our twenty-year fight,” Rosenberg wrote in his diary, seething. “History will perhaps one day clarify if the situation that arose must have arisen.” He could only hope that it was another of the Führer’s strokes of strategic brilliance, a momentary alliance of convenience before Germany returned to the long-term plan Rosenberg had envisioned all along, which was not to befriend the communists but to annihilate them.

He needed to see Hitler. He needed to understand what had happened.

The pact had grown out of Hitler’s plans for the invasion of Poland. While his generals put together the military plans, the Führer began to smooth the diplomatic path. He did not want war with Britain in the West—not yet—and he could not afford a confrontation with the Soviet Union in the East.

Mulling over his geopolitical predicament, the German dictator consulted a foreign minister who, in the opinion of nearly everyone but Hitler, lacked the diplomatic acumen and political judgment to handle the questions at hand. Even Rosenberg, no master of tact himself, could see that. “That he is his own worst enemy with his vanity and arrogance … is not a secret,” he wrote in 1936. “I have put this down in letters to him—the way he conducted himself from the moment the sun began to shine on him.”

Ribbentrop’s was a cultured upbringing. After his mother died, his father married the daughter of an aristocrat. He was no nobleman himself; as an adult, he would earn the right to use “von” in his name only by paying a distant relative to adopt him. Ribbentrop grew up playing tennis and the violin, lived for a time as a teenager in the Swiss Alps, studied in London for a year, and at seventeen sailed with friends to Canada, where he spent the next four years falling in love with a woman and building a wine import business.

The First World War brought him back to Germany. Starting over after the armistice, he built a successful wine and liquor business and became a wealthy man. In 1932, he joined the Nazi Party, and early the next year he found himself in a position to help midwife the deal that handed Hitler the reins of power. Ribbentrop had served in Constantinople during the war with Franz von Papen, who rose to the chancellorship in 1932 and who, during those fateful weeks in January 1933, had Hindenburg’s ear. Ribbentrop spent that month shuttling between Papen and Hitler as the two men negotiated a division of power. Pivotal secret meetings took place in Ribbentrop’s villa in the wealthy Berlin neighborhood of Dahlem, with Papen arriving in Ribbentrop’s limousine and Hitler sneaking in quietly through the garden. “His acting as an intermediary in 1932 was very important to the Führer,” Rosenberg wrote later in the diary, “and he feels extraordinarily indebted to Ribbentrop.”

The first time Ribbentrop spoke with the future Führer, at a 1932 party Ribbentrop hosted, the men talked at length about Britain. Ribbentrop had lived in London only briefly, but the conversation must have stuck in Hitler’s memory, because from then on he—quite wrongly—considered the wine dealer an expert on the empire. “It was the harmony of our views about England,” Ribbentrop recalled, “which on this first evening spent together created the seed of confidence between Hitler and myself.”

In the early days of the Third Reich, Ribbentrop used his status in the Nazi ranks to secure meetings with British and French officials. Unbeknownst to Hitler, the international diplomats considered him a lightweight. He was unschooled in foreign policy protocol, he was a clumsy and duplicitous negotiator, and he managed to be both ignorant and arrogant. None of this stopped Hitler from giving the diplomat his own foreign affairs task force, the Büro Ribbentrop, and sending him to London to negotiate an important naval agreement with the Brits. To the amazement of his many enemies, including Rosenberg, Ribbentrop succeeded, and in 1936 Hitler named him ambassador to England. But as he worked to mend fences, the Brits repeatedly rebuffed his unsophisticated approaches, and began referring to him as “Herr von Brickendrop” and “von Ribbensnob.” Hitler was impressed that Ribbentrop seemed to know all the key figures in British politics, to which Göring replied: “Yes—but the trouble is, they know Ribbentrop.” Failing to win over the British, Ribbentrop instead turned resolutely against them.

Hitler named Ribbentrop foreign minister in 1938, and a year later Ribbentrop told the Führer not to worry about Britain’s reaction to the planned invasion. Just as they had looked the other way on Czechoslovakia, Ribbentrop promised, the Brits would not go to war over Poland.

Hitler accepted that dangerously misguided counsel, and looked east for an alliance.

By the spring of 1939, it was public knowledge that Britain and France were negotiating a coalition with the Soviets to block Nazi aggression in Poland. Hitler may have fulminated against the Soviets for years, but now, facing powerful enemies in the West just as the shooting was about to start, he decided to do whatever it took to get Stalin on his side. So as Hitler’s invasion deadline approached—September 1, the better to avoid the mud come autumn—the Nazis worked against the clock to cut a deal.

Stalin, suspicious of the Western democracies and as coldly practical as Hitler himself, was already open to the idea of joining hands with the Nazis. He feared that all he would get from an alliance with Britain and France was a world war, the costs of which would fall disproportionately on his nation as the sole bulwark along the lengthy front in the East.

Months of talks and telegrams between Germany and the Soviet Union came to a head on August 20, when Hitler wrote Stalin to say he wanted to finalize the pact “as soon as possible,” for the “crisis” in Poland could erupt at any time. “The tension between Germany and Poland,” he wrote, “has become intolerable.”

At 9:35 p.m. the next day, Stalin cabled his agreement. “The assent of the German Government to the conclusion of a nonaggression pact,” he wrote, “provides the foundation for eliminating the political tension and for the establishment of peace and collaboration between our countries.”

The news was immediately broadcast on German radio, and two days later Ribbentrop flew to Moscow to discuss the particulars.

He met for three hours in the afternoon with the Soviets and then returned in the evening, but there were no real disagreements, even when it came to a secret codicil carving up the lands between the two countries. The Soviets would get the Baltics to the north of Lithuania, and the two nations would split Poland along its major rivers. Most of the night, in fact, was spent not hammering out technical details but swapping opinions about international affairs and saluting each other with warm—and repeated—toasts. “I know how much the German nation loves its Führer,” Stalin said when it was his turn. “I should therefore like to drink to his health.” Then the men drank to Stalin’s health, and to Ribbentrop’s, and to the Reich, and to their new relationship.

In the early-morning hours, before the meeting broke up, Stalin pulled Ribbentrop aside to tell him how seriously he would take their new pact. He guaranteed on his honor that he would not be the one to break it.

Rosenberg, as the Third Reich’s most committed anti-communist, had been necessarily left out of the loop during the negotiations leading up to the deal. All along, he had been hoping that Germany could come to a power-sharing agreement with Britain. These were two Aryan nations that should work with each other, not steel themselves for war. They should stand together to rule as masters over the world. But this wasn’t going to happen, and he bitterly blamed Ribbentrop—this “joke of world history,” Rosenberg called him—for mishandling affairs in Britain. Ribbentrop had done nothing to foster goodwill; he had done the opposite. “In London itself, v. R., who after all had been sent there on account of his alleged ‘connections,’ put everybody’s nose out of joint,” Rosenberg wrote in the diary. “Undoubtedly, much was due to his individual personality.” Rosenberg had apparently forgotten his own disastrous goodwill mission to England years before.

“I’m of the conviction that he’s conducted himself with England just as stupidly and arrogantly as he has here,” Rosenberg remembered telling Göring earlier in the year, “and therefore has been just as personally rejected.”

The foreign minister really had only one friend in Germany, Göring replied, and that was Hitler. “Is von Ribbentrop a clown or an idiot?”

“A really stupid individual,” Rosenberg muttered, “with the usual arrogance.”

“He’d bluffed us with his ‘connections.’ When you looked closer at the French counts and English aristocrats [he knew], they were owners of champagne, whiskey, and cognac factories,” Göring said. “Today the idiot believes he has to play the ‘Iron Chancellor’ everywhere,” he said. “However: Such an imbecile takes care of himself, bit by bit; only he can bring about terrible calamity.”

Now, with the Moscow pact, that calamity had arrived. Rosenberg’s loyalty to Hitler was suddenly in conflict with his certainty that the Führer had made an error of disastrous proportions. Rosenberg could understand a temporary alliance; he claimed he had even spoken about such a duplicitous arrangement with Göring once. This did not sound temporary. The newspapers were declaring Germans and Russians to be traditional friends and allies. “As if our fight against Moscow had been a misunderstanding, and the Bolsheviks were the true Russians, with all the Soviet Jews at the top! This little embrace is more than embarrassing.”

Rosenberg, always willing to bow to his hero’s wisdom, tried to convince himself that Hitler had had no choice but to reach an accord with the Soviets before Britain and France did. It had been a matter of self-preservation. “The Führer’s change of direction,” he acknowledged in the diary, “was probably a necessity in light of the given situation.” And yet he could not shake the sense that Hitler was taking a major gamble.

“I have the feeling that this Moscow pact will eventually have dire consequences for National Socialism,” he wrote in the diary. “It was not a step taken freely, but rather an action from a forced position—a supplication on behalf of one revolution to the head of another … How can we speak of the rescue and reshaping of Europe when we must ask the destroyer of Europe for help?

“And now the question arises once more: Did this situation have to arise? Did the Polish question have to be solved now and in this form?”

No one, he thought, had answers to any of those questions.

“Close your hearts to pity!” Hitler told his military commanders ten days before sending his armies off to war against Poland. “Act brutally! … Be harsh and remorseless! Be steeled against all signs of compassion!” He did not want the army to simply defeat the Polish forces; he wanted “the physical annihilation of the enemy … I have put my Death’s Head formations at the lead with the command to send man, woman, and child of Polish descent and language to their deaths, pitilessly and remorselessly.”

Hitler’s savagery was, as ever, rooted in racial bias: All Germans learned at an early age that the Poles were a disorderly, primitive people who deserved to be ruled by strong masters. At the same time, geographic realities were at play: Poland stood in the way of Germany’s eastward expansion, and the leaders in Warsaw had enraged Hitler by rejecting his boisterous demand for territorial concessions.

So on the first of September, the Germans roared across the border from the north, south, and west: one and a half million men, three hundred thousand horses pulling artillery and matériel, fifteen hundred tanks, hundreds of the Luftwaffe’s new planes. Against this Blitzkrieg—literally, “lightning war”—the Poles stood no chance. Their lines were strafed by fight...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Prologue: The Vault

- Lost and Found: 1949–2013

- Lives in the Balance: 1918–1939

- At War: 1939–1946

- Epilogue

- Appendix A: A Third Reich Timeline

- Appendix B: Cast of Characters

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- Also by Robert K. Wittman and David Kinney

- About the Publisher