- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

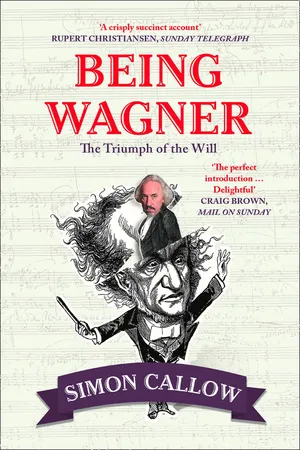

Yes, you can access Being Wagner by Simon Callow in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Music BiographiesONE

Young Richard

In 1813, when Wagner was born, the instability which is at the heart of his temperament and his work was the universal condition. Napoleon’s plans for world dominion were unravelling, but not quickly, and not without massive fallout. A year after their humiliating defeat in Russia in 1812, in October 1813 the French, fielding an army of young untried soldiers, fought a savage battle almost literally on Wagner’s doorstep, right in the centre of the city of Leipzig where he had been born, five months earlier, on 22 May, in a modest apartment over a pub in the Jewish district. Leipzig was the second city of the newly created kingdom of Saxony-Anhalt, one of the nearly forty sovereign states that constituted the hollow remnant of the Holy Roman Empire, itself the heir to the Western Roman Empire. Germany as such existed only as an idea. An increasingly potent idea, but an idea nonetheless. The Saxons were Napoleon’s allies, and along with the French they were brutally crushed in October 1813 by the brilliantly organised coalition of Prussian, Swedish, Austrian and Russian forces; during the battle – the biggest engagement in military history before the First World War – Napoleon’s armies were in and around the city, fighting and losing the heaviest pitched battle of the entire interminable war. Over the three days of the battle there were 100,000 losses, near enough: 45,000 French, 54,000 allies; just disposing of the corpses was a huge undertaking, and rotting bodies were still visible six months after the cessation of hostilities. The citizens were in a state of abject terror. The world seemed to be falling apart: and it was. Nothing would be the same again. Wagner claimed that his father, Carl Friedrich Wagner, a clerk in the police service, died during the hostilities as a result of the stress – that, and the nervous fever which had seized the city.

Richard, no stranger himself to nervous fever, of both the physical and the creative variety, was the ninth and last of the Wagners’ children. He was baptised in St Thomas’s church, the very church where Johann Sebastian Bach, in the previous century, had served as cantor for twenty-five years. This omen was not followed any time soon by evidence of musical gifts in the child; indeed, as a little boy Richard’s inclination and talent were all for the theatre, no doubt because his mother’s new husband, Ludwig Geyer, a family friend, was an actor. Wagner’s mother Johanna had remarried just nine months after her first husband’s death; young Richard was given his stepfather’s name and was accordingly known for his first fourteen years as Richard Geyer. Some fifty years later, Wagner came upon passionate letters from Geyer written to Johanna while her first husband was still alive; it was clear from them that she and Geyer were already lovers. So whose son was he? The police clerk’s, or the actor’s? Who was he? Like more than one of his characters, he could never be entirely sure, but it was Ludwig Geyer’s portrait he carried around with him to the day he died – not Carl Friedrich Wagner’s.

After the marriage, the newly-weds moved, with the children, to the Saxon capital, Dresden, where Geyer was a member of the royal theatre company. Little Richard’s new life was highly agreeable to him: Geyer, a deft and successful portrait painter as well as an actor, was a kind, funny step-father and the house was always aswarm with theatre people and musicians, among them Carl Maria von Weber. The great composer was music director of the Dresden opera, but also conductor of the theatre company, for whose productions he wrote incidental music. Wagner remembered him being in and out of the house all day long, hobbling around bandy-legged, his huge spectacles on the end of his large nose and wearing a long, grey, old-fashioned coat like something out of one of Wagner’s favourite E. T. A. Hoffmann stories. The boy was an insatiable reader, losing himself in the newly published fairy tales collected by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm; though showing no gift for performing music, he was obsessed by it, listening spellbound to the military brass bands which paraded up and down the streets, tootling out good old German folk tunes. Best of all, he had easy access to the theatre, where he could play as long as he liked in the props shop and the wardrobe department; he had no skills as a painter, Geyer noted, but his imagination knew no bounds, and his stepfather encouraged it.

And then, quite suddenly, Geyer was gone, when Richard was just eight, struck down at the age of forty-two. Arriving at the deathbed, the boy was sent to the room next door by his sobbing mother and told to play something: he had had some elementary lessons in the little country school he attended, and obliged with ‘Üb immer treu und Redlichkeit’, a sober transformation of Papageno’s playful ditty ‘Ein mädchen oder Weibchen’ from The Magic Flute, with pious words to match:

Use always fidelity and honesty

Up to your cold grave;

And stray not one inch

From the ways of the Lord

Hearing the lad play the sombre little piece, Geyer murmured, as he slipped away, ‘Is it possible the boy has some talent?’

Once Geyer was dead – the second father Wagner had lost – little thought was given to his dying question: her youngest son’s musical abilities was low on the widow’s list of priorities. The decent sum of money Geyer had left her soon ran out; Johanna took in lodgers, including, for a time, the distinguished composer and violinist Louis Spohr, so music was always in the air. In a household filled with musically gifted children, only Richard had shown no aptitude for performing it, as his mother helpfully informed Weber, in Richard’s presence. In fact, apparently unnoticed by Johanna, he was utterly consumed by music. The sound of a brass band tuning up put him, he said, into a state of mystic excitement; the striking of fifths on the violins seemed to him like a greeting from the spirit world. Later he developed a crush on a young man who played the overture to Weber’s new opera Der Freischütz on the piano. Whenever the hapless youth came to the house, Richard begged him to play it over and over and over again. At twelve, he finally persuaded his mother to let him have piano lessons, which he continued with only up to the point where he was able to bash out the Freischütz overture for himself. From then on he bashed out every score he could get his hands on; his skill at the piano never improved to the end of his days. All his performances – and he was a compulsive performer – were a triumph of feeling over technique and mind over fingers; the same effort of will and imagination somehow, fifty years later, enabled him to play and sing through the entire Ring cycle, evidently to overwhelming effect.

For a year after Geyer’s death, to save money, young Richard had been shunted aimlessly around his relatives, from Eisleben to Leipzig and back again; en route he picked up the art of acrobatics, a skill he proudly displayed to the end of his life, manifesting startling flexibility in his late sixties. Back in Dresden at last, he was sent to the city’s famous old grammar school, the Nicolaischule. Johanna was determined that he should be properly educated, desperate above all else that he should never become an actor. Three out of her nine children had done so, with some success, but to her the theatre was beneath contempt, barely an art at all, certainly not to be compared with the poetry or the painting she so admired. Severe – Wagner said he could never once remember her having embraced him – and strongly pious, she was given to leading impromptu family prayer sessions from her bed, dispensing moral precepts to each of her children in turn. She was determined to make a serious young man out of Richard.

All in vain. He was a terrible student, lazy and wilful, refusing to study anything that failed to engage his imagination, which left exactly two subjects: history and literature – ancient Greek history and literature to be precise, with a bit of Shakespeare thrown in. His forte was recitation. At twelve, he made a big success speaking Hector’s farewell from the Iliad, followed by ‘To be or not to be’ – in German, of course, both of them: languages, he said, were too much like hard work. Nevertheless, even in translation, Greek plays, Greek myths, and Greek history grabbed him by the throat from an early age. He wrote copiously himself, great poetic screeds, blood-spattered epics: it was the gruesome, he said, that aroused his keenest interest, invading his dreams, and giving him, night after night, shattering nightmares from which he would wake shrieking; understandably his brothers and sisters refused to sleep in the same room with him. He seems to have been, to put it mildly, a bit of a problem child. There may have been some anxiety – some uncertainty – in the air. There was very likely a sense in the household that Richard was Geyer’s son. Nor did he fit in at school: a histrionic, hyperactive, oversensitive little chap with a nasty habit of bursting into tears every five minutes, but nonetheless he somehow managed to corral some of his school fellows into giving a performance (heavily abridged, one can only assume) of his favourite opera, Weber’s Der Freischütz. In the opera a young man with ambitions to succeed the Head Forester and marry his daughter is outshot by a rival; frustrated, he turns to his saturnine colleague Kaspar, who gives him a magic bullet, promising to give him more if he will come with him to the Wolf’s Ravine, which is where they go at the end of the second act.

In that famous scene, which terrified its first audiences and positively obsessed the young Wagner, the central characters, the hero Max and his darkly brooding friend Kaspar, repair at midnight to the fearsome ravine, deep in the woods. The clearing they are heading for is a vertiginously deep woodland glen, planted with pines and surrounded by high mountains, out of which a waterfall roars. The full moon shines wanly; in the foreground is a withered tree struck by lightning and decayed inside; it seems to glow with an unearthly lustre. On the gnarled branch of another tree sits a huge owl with fiery, circling eyes; on another perch crows and wood birds. Kaspar, in thrall to the devil, is laying out a circle of black boulders in the middle of which is a skull; a few paces away are a pair of torn-off eagle’s wings, a casting ladle, and a bullet mould:

Moonmilk fell on weeds!

Uhui!

moans a chorus of Invisible Spirits,

Spiders web is dewed with blood!

Uhui!

Ere the evening falls again –

Uhui!

Will the gentle bride be slain!

Uhui!

E’re the next descent of night,

Will the sacrifice be done!

Uhui! Uhui!

In the distance, the clock strikes twelve. Kaspar completes the circle of stones, pulls his hunting knife out and plunges it into the skull. Then, raising the knife with the skull impaled on it, he turns round three times and calls out:

Samiel! Samiel! Appear!

By the wizard’s cranium,

Samiel, Samiel, appear!

Samiel appears. Kaspar, who has already sold his soul to this woodland devil, tries to do a deal with it: Samiel can have Max instead of him. The Spirit agrees; Max, knowing nothing of this, arrives and together – in spite of a scary warning from his mother’s ghost, which suddenly looms up – he and Kaspar cast seven magic bullets, six of which will find their mark, the seventh will go wherever Samiel decrees. Finally, at the very last moment, and thanks to the intervention of an ancient hermit, the seventh bullet, instead of killing Max, finds its way into Kaspar’s heart. Max is redeemed, and is free to marry his beloved Agathe.

Despite the redemptive ending this is gruesome stuff, all right, and strangely disturbing. The old story stirs up memories of a pagan German past, of nomadic warriors who come from the dark and terrible forest, where, in the grip of demonic powers, they commune with spirits. Weber tapped into all of that, creating German Romantic opera at a stroke, and scaring the pants off his audiences, not least sixteen-year-old Richard Wagner; its atmosphere, and its music, entered into his soul.

Meanwhile his flagrant neglect of his schoolwork finally forced a crisis, which he precipitated by disclosing to his family that he had written a play, Leubald and Adelaïde, loosely based, he said, on Hamlet, King Lear, Richard III and Macbeth, with a few bits of Goethe’s Götz von Berlichingen thrown in for good measure. It was essentially Hamlet, he said, with the interesting difference that the hero, visited by the ghost of his murdered father, is driven to acts of homicidal revenge and goes mad – really mad, unlike Hamlet: in a frenzy, he stabs his girlfriend to death then, in a final blood-drenched tableau, he kills himself. The total roll call of the dead by the end of the play is forty-two. Or so Wagner said. In fact, as the recently rediscovered text reveals, it was no more than twelve, which tells us that Wagner was not averse to sending up his youthful self.

Whether it was twelve corpses or forty-two, the family were horrified to think what dark and desperate thoughts, how much violence and death, were swirling around inside the sixteen-year-old’s brain. Not least disturbing among the play’s catalogue of murders, rape and incestuous love – Adelaide is Leubald’s half-sister – is the prominence given to the Hamlet-like murder of Leubald’s father by his own brother; he then swiftly marries the widow, which might have seemed rather close to home for Johanna Wagner. All through the outraged tirades which rained down on his head, Wagner was laughing inwardly, he said, because they didn’t know what he knew: that his work could only be rightly judged when set to music, music which he himself would write – was indeed about to start composing immediately. The fact that he had no idea how to go about such a thing was a minor obstacle. Under his own steam, he found a fee-paying music lending library and took out Johann Bernhard Logier’s elementary compositional handbook, Method of Thorough-bass. He kept it so long, studying it so intently, that the fees accumulated alarmingly; the words ‘borrow’ and ‘own’ were always interchangeable in Wagner’s mind. This particular music lending library was, as it happens, run by the implacable Friedrich Wieck, whose daughter Clara was before very long about to defy him by marrying Robert Schumann; Wagner failed to deflect him, and so, at the age of sixteen, he found himself being pursued for debt, an experience with which he would become all too familiar. His family was eventually called on to bail him out; that too was a pattern that became wearyingly familiar.

His family’s dismay at having to pay was matched by their horror at discovering the nature of Richard’s musical ambitions: to be an aspiring performer is one thing – at least there is a chance of earning a living. But to want to be a composer is quite another thing, a recipe for penury. He was not to be gainsaid: the willpower that was to drive his life forward was already fully formed: he was going to be a composer. Faced with the inevitable, the family procured him lessons in harmony (which bored him) and in violin (which tortured them), but neither the boredom nor the torture lasted very long: no sooner were both begun than they were abandoned. He went his own way; for him it was the only way possible. What really mattered to him was cultivating his imagination. He immersed himself in the writing of that phenomenal figure Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann – critic, composer, storyteller, journalist, embodiment and avatar of everything that was dark and fantastical in German Romanticism. Above all for the young Wagner, Hoffmann was the creator of the misunderstood musical genius Johannes Kreisler, rejected by society but certain of his own greatness; for Kreisler music is nothing less than a form of possession:

Unable to utter a word, Kreisler seated himself at the grand piano and struck the first chords of the duet as if dazed and confused by some strange intoxication … in the greatest agitation of mind, with an ardour which, in performance, was certain to enrapture anyone to whom Heaven had granted an even passable ear … soon both voices rose on the waves of the song like shimmering swans, now aspiring to rise aloft, to the radiant, golden clouds with the beat of rushing wings, now to sink dying in a sweet amorous embrace in the roaring currents of chords, until deep sighs heralded the proximity of death, and with a wild cry of pain the last Addio welled like a fount of blood from the wounded breast.

Young Wagner gobbled up these stories, as well as devouring Hoffmann’s intensely imagined analyses of Beethoven’s music – less critical appreciation than Dionysiac trance.

Beethoven’s instrumental music unveils before us the realm of the mighty and the immeasurable. Here shining rays of light shoot through the darkness of night and we become aware of giant shadows swaying back and forth, moving ever closer around us and destroying us but not the pain of infinite yearning, in which every desire, leaping up in sounds of exultation, sinks back and disappears. Only in this pain, in which love, hope and joy are consumed without being destroyed, which threatens to burst our hearts with a full-chorused cry of all the passions, do we live on as ecstatic visionaries

– which could easily be a description of Wagner’s own mature music. Intoxicated with all this, the seventeen-year-old plunged in at the deep end, applying himself to the monumental task of making a piano transcription of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony – a work written, in the view of most contemporary musicians, when the composer was already half mad. That was in itself enough to recommend it to Wagner. Weber had remarked on hearing the first performance of the Seventh Symphony that Beethoven was ‘ripe for the madhouse’; and the Ninth went further. It was the nineteenth century’s Rite of Spring, considered unplayable, incoherent, crude, the ne plus ultra of all that was fantastic and incomprehensible. To Wagner it became, in his own words, ‘the mystical goal of all the strange thoughts and desires’ he had concerning music; the opening sustained fifths, he said, seemed to him to be the spiritual keynote of his own life. Its darkness, its mystery, its implication of profound chaos, found an answering echo in his teenage soul, and never ceased to connect to him at the deepest level. He returned to this music again and again throughout his life; it was played at the opening of the first Bayreuth Festival and has been played at every opening since. It was, he felt, what music should be. What his music should be, though he had no idea how that might come to pass. The adolescent Wagner was almost morbidly susceptible to impressions; they overwhelmed his mind and his imagination, entering him like viruses, stirring up an inner furor, stoking his heightened sense of being, setting him on fire, mentally and physically. Encountering the Ninth Symphony of Beethoven was the overwhelming experience of his young manhood.

The next massive hit his system took, he said, was seeing the soprano Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient in Fidelio, in the Leipzig theatre. Schröder-Devrient, then just twenty-eight, was the Maria Callas of her day: vocally unreliable, but expressively thrilling, every note, every word, every gesture deeply imbued with meaning. He despised the operatic performers he had seen up to that point: staring straight out at the audience, rooted to the spot, playing to the gallery, straining for stratospheric top notes. The vehicles in which they performed were equally beneath contempt; to the young Wagner,...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Foreword

- Vorspiel

- 1 Young Richard

- 2 Out in the World

- 3 Doldrums

- 4 Triumph

- 5 The World in Flames

- 6 Pause for Thought

- 7 It Begins

- 8 Suspension

- 9 Limbo

- 10 Enter a Swan

- 11 Towards the Green Hill

- 12 The Long Day’s Task is Done

- Coda

- Chronology

- Wagner’s Works

- Bibliography

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Index

- By the Same Author

- About the Author

- About the Publisher