- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

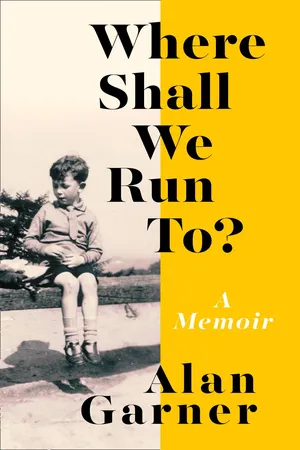

Yes, you can access Where Shall We Run To? by Alan Garner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Porch

Our house was on Trafford Road where Stevens Street meets Moss Lane. It wasn’t like any of the other houses. It was smaller and older, and had no garden at the front, only the footpath. That was because it had been a toll gate, people said. Big Sam Woodall, who walked without moving his arms, used to come and stare in at the window, but he was some kind of cousin to my father and meant no harm. There was a chimney at either end, a porch in the middle, and four windows, one in each corner. The window frames were made of stone set in the brick and had a stone pillar between the panes of glass.

The bedroom windows were so low, if the postman arrived when we were asleep he knocked ‘Birkett-and-Bostock’s-brown-bread’ on the door and my father opened the window and the postman handed the letters up to him.

(© Estate of Charles Keeping)

There were three rooms downstairs. The one we lived in was called the House. That had the door to the porch and the road. The stone floor was covered with bits of linoleum, which were good for sliding on in my stocking feet, and rag rugs which my mother made from cut-up old clothes pushed into the webbing of a string net she knitted. The next room was the Middle Room. It had no furniture and I kept my budgerigar in a cage there. We used the Middle Room to get to the Scullery. The Scullery was the room where the slopstone and water tap were and it had been added along the back wall. Outside were the coal shed and the lavatory, and a grid for the pipe through the wall from the slopstone. The grid had green jelly on it and I used to play with it when I was little. I didn’t like the taste, though. And I once ate a grey slug, but it was gritty.

There was a big copper in the Scullery, set in brick with a fire grate under it for heating the water for Monday wash day and Friday bath night. The tin bath hung on a nail in the wall, and there was a dolly tub and a mangle for the washing.

The dolly was a pole with a T-handle at the top and a round piece of wood with three legs at the bottom. When I was big enough, I used to twirl the clothes in the dolly tub with the handle to make the dolly’s legs work the soap in. Then I twirled with clean water to rinse the clothes. Then I turned the mangle to squeeze out the water, and tried not to get my fingers caught in the rollers. My mother hung the washing to dry in the garden, but if it rained she hung it on the clothes maiden in front of the fire in the House and steamed up the windows.

The clothes pegs were cut from willow branches, split at one end and bound with a strip of tin at the other. My mother bought them in bundles from Gypsy women, five to a bundle for sixpence. The women went from door to door along Trafford Road, and when they reached our house my mother let them into the garden at the back and gave them chairs to sit on so they could feed their babies, and she made them cups of tea. They thanked her and blessed her and sold her some pegs and went on their way.

The Gypsies were exciting. They had dark hair and skin and eyes, and they wore ear rings and bangles and bright clothes, even when the war was on. And they smelt more like cats than people.

Once, a woman was sitting and feeding her baby, and she stroked my head, lifted my chin and looked into my eyes. She told my mother I would grow up to be a big man, but she must watch out for trouble with my kidneys.

Soon after the women left, the men arrived, selling from door to door, each carrying a roll of linoleum on his shoulder, or a carpet, or a rug, or a piece of furniture, or a stick with rabbits hanging from it, skinned and gutted and without their heads, but with the paws left on to show they weren’t cats. And when the men reached our house they didn’t stop. I wondered why they didn’t stop; and one day, after the women had left, I went into the road and looked at the house.

There was a chalk mark on a brick low down in the porch. It wasn’t writing and it wasn’t a picture; just a squiggle. But it hadn’t been there earlier. So I remembered it. And if a tramp or the Singing Woman came begging in the village, I put the squiggle on the porch; and we were never bothered.

(© the author)

The fire range in the House was made of heavy iron, which my mother cleaned with emery paper and polished with black lead every week. There were three bars at the front, built up behind to make the fire high but narrow, so that coal and heat weren’t wasted. On the left was a boiler for water and a hotplate, and on the right an oven with sliding dampers to control the heat. My Hough grandad Joseph had put the range in when he was a young man, and Joseph Sparkes Hall, my mother’s great-grandfather’s nephew, had invented it and shown it at The Paris Exhibition of 1867 as ‘The English Cottage, or Test House’. He’d also invented the elastic-sided boot and had been Bootmaker to Queen Victoria and to the Queen of the Belgians; and he’d written The Book of the Feet. My grandma told me that. And she had some of his letters and business cards and a photograph of him with another of his inventions.

(© the author)

Along the front of the range was a copper fender with a pattern of leaves on it; and at each end was a buffet, where I sat to read or to watch the pictures in the fire. I used to spit on the iron bars to see the spit dance and bubble and disappear.

The range fitted inside a big chimney space, and if I looked up it when the fire was out I could see the sky.

My mother raked the ashes every morning before lighting the fire. She lit the fire by putting a scrumpled piece of paper in the grate. Then she rolled a sheet of newspaper tightly from corner to corner to make a paper rod, and bent the rod in two places to make a triangle, folded the two crossed pieces over and put them through the triangle so the loose ends stuck out equal. She made three of these and laid them on the scrumpled paper together with sticks we’d brought from the Woodhill. Then around the top she put cinders that hadn’t burned through properly the night before and added a few small pieces of coal; and then she lit the scrumpled paper with a match, and the fire soon brightened up so she could put bigger pieces of coal on to make a nest for the kettle to sit in to boil the water to mash a pot of tea for when my father came down for his breakfast. Then she got breakfast ready while the kettle boiled.

One morning, though, as the kettle was singing and starting to boil, a lump of soot fell down the chimney and knocked the kettle over. It put the fire out and nearly scalded me, and my father was vexed because he had to go to work without having his brew. My mother said he should have swept the chimney. And he said she must keep the fire out, which meant we had no hot water all day.

That night he came home with a brush and rods he’d borrowed from a chimney sweep, and he’d brought dust sheets from work. He covered the floor with the sheets, and the furniture and the walls and the fireplace, leaving a gap to push the brush through. Then he swept the chimney.

The head of the brush was round and the bristles stuck out sideways in a circle. The rods screwed into the head and then into each other in brass sockets.

My father stuck the brush up the chimney and twirled it and pushed to bring the soot down.

When he’d pushed the brush up as far as he could reach, he screwed another rod in and pushed again. The soot fell down the chimney into the grate, and some got into the room through gaps in the sheets and made our faces black.

My mother asked my father if he’d got enough rods to reach the chimney pot, and he said of course he had and it was easy now, so he must be nearly at the top. Then he fitted another rod, and pushed; and then he stopped. He pushed and twisted again, but the brush wouldn’t move. He said he must have reached the chimney pot, but that didn’t matter because it meant the chimney was clean and any soot in the pot wouldn’t hurt, it was that high up.

He started to pull the brush back down, but it didn’t move. He rattled the rods, but the brush was stuck. He tried again, harder, and again, and my mother told him to stop because he might loosen the chimney pot or break it, if he hadn’t done already.

We went out to see.

The chimney pot was all right; but the rods were sticking out of it high into the air, and they’d bent over and down and the brush was all tangled in the telephone wires.

My mother began to nag at him, but my father told her to give over mithering. She’d said he must sweep the chimney, and he had.

There were two bedrooms in our house. The stairs went up nine steps through my room, with a rail and curtains around the top and two big cardboard pictures of Newfoundland Landseer dogs, and there was a door to my parents’ bedroom. When I was ill I had a wooden cotton bobbin on a string and used to drop it from my bed on people’s heads as they were going up. And in summer, if the weather was hot, I used to sleep across the end of the bed with my feet out of the window.

One day, when I was ill, an old man with white hair stopped to talk to me from the footpath. He said when he was a boy he used to play with the boy that lived here, and there were no stairs, only a ladder by the chimney of the fireplace. And when I looked I could see where it had been.

Something else about our house was different. It felt bigger inside than out. That was because the floors of the rooms were bigger, and the downstairs ceilings were lower, than the other houses in the road. Their high ceilings made them seem smaller too. And our bedroom ceilings weren’t flat. They sloped up to the beam at the top, and there were more beams, upstairs and down, and the walls weren’t straight. The humps and cracks and bumps made pictures, but the other houses had only flat paper with patterns on.

I loved the house, and I asked my mother if I could live there for ever when I grew up, and she said I could. But when my grandma got too old to look after herself we had to move into one of those other houses so she could be with us. It was fifty yards away, and I hated it because the walls were straight.

The most important part of the real house was the porch. The house roof had ordinary slates, but the porch had stone slabs, and a houseleek grew on the slabs.

The houseleek was there to save us from being struck by lightning. It grew on a heap of mossy roots and had leaves in round clumps. The leaves were thick and fleshy, with a prickly point, and the juice from them was good for curing sore eyes. Mrs Nixon had sore eyes and she used to come and ask for a leaf¸ which she squeezed and the juice dripped into her eyes and made her blink. When we moved, my mother took the houseleek and put it on the new coal shed. I didn’t want her to do that, because it was more important to save the real house.

The porch was my den. It was inside and outside at the same time. I played there when I was little, and when I was older I put a chair in it so I could read, and count my stamp collection and look out at what was happening.

My mother donkey stoned the flags of the porch every week with a soft stone like a brick with a galloping donkey carved on it. She dipped the stone in a bucket of cold water and scrubbed the flags white all over. We got the donkey stone from the Rag-and-Bone Man, who came round on a flat cart drawn by a pony. He sat at the front corner, holding the reins and calling, ‘Ragbone! Ragbone! Any rags? Pots for rags! Donkey stone!’ and I gave him bits of rubbish and scraps and worn-out cloths, and he gave me a donkey stone for a swap.

Once, when I was in the porch, Mr Perrin, who lived down Moss Lane and worked in a cake shop, was passing by and he asked me if my grandad’s name was Joe, and I said no, his name was grandad. That made him laugh. And he left a cup cake with white icing and half a cherry on top for me every day after, in the porch, round the corner where no one else could see it.

When the King died, the Prince of Wales became King Edward VIII. But before he was crowned he said he didn’t want to be King, so his brother, the Duke of York, was King George VI instead. There was a lot of excitement, and my mother hung a cardboard picture in the porch showing the new King and Queen on a Union Jack, with the letters GOD BLESS KING GEORGE VI in gold.

A few days before the Coronation it rained, and the next morning the picture had peeled off and below it was another picture, the same but showing the Prince of Wales and GOD BLESS KING EDWARD VIII. My mother took it down and burned it.

Until the war started, on Guy Fawkes Night boys used to sneak into the porch and put rip-raps through the letterbox, and the rip-raps jumped around and my parents had to stamp them out to stop them setting the house on fire. And one year, my father heard a scuffling in the porch. The front door was heavy and opened outwards. My father crept to the door, listened, and waited. He heard a giggle, and he opened the door hard against the wall of the porch to trap the boys and shouted ‘Got you!’ But when he looked it was a courting couple squashed together and the young woman began screaming. He shut the door and switched off the light and we sat by the fire till the noise and the man’s shouting went away.

I liked singing, and my grandma taught me Negro Spirituals, which she played on her piano. When Miss Fletcher heard about this she made me give a concert to the Infants after Prayers. I sang my favourites: ‘Poor Old Joe’, ‘Swing Low, Sweet Chariot’ and ‘All God’s Chillun Got Wings’. And then the choirmaster from St Philip’s church heard about it and he tried to make me join the choir. I went to choir practice once, but I didn’t like it, because I couldn’t read the music and couldn’t understand what he was talking about and some of the others in the choir kept changing the tune and I didn’t know which was right, so I didn’t go again.

A few times, my father came back from the pub with his friends, and if I was in bed he got me up to sing for them. I was shy, and the only way I could sing was to go behind the blanket that hung over the front door to stop the draught, and I sang there where I couldn’t be seen. I sang the songs we heard on the wireless, not Negro Spirituals. I sang ‘Toodle-uma-luma-luma’, ‘Doing the Lambeth Walk’, ‘Ain’t She Sweet?’ and ‘Ragtime Cowboy Joe’.

It was good when I sang behind the blanket because of the smell and the tickle of the doormat on my feet and the sound of the wind in the porch and through the letterbox.

One night, my father brought his friends home when the pubs closed, and they had bottles of beer and whisky with them, because my father had been called up to join the army the next day. He’d already said goodbye to my Hough grandad and uncles at The Trafford Arms.

I had to sing a lot of songs, and I got cold from standing behind the curtain and went and sat on a buffet by the fire to get my feet warm. I didn’t like the smell of the beer and the whisky and the cigarette smoke, and the men were talking and laughing loudly and their faces were red. They laughed every time anyone said anything, but I didn’t get the jokes.

One of the men, Fred Taggart, who lived down Moss Lane, wanted to go to the lavatory, and my father took him through the Middle Room to the Scullery where the back door was. He didn’t have a torch, and my father told him to follow the wall to the corner and then ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Bomb

- The Nettling of Harold

- Rocking Horse

- Monsall

- Porch

- Mrs E. Paminondas

- Mrs Finch’s Gatepost

- St Mary’s Vaccies

- Widdershins

- Bunty

- Bike

- Mr Noon

- Half-Chick

- DOWN MOSS LANE

- Bomb (1955)

- St Mary’s Vaccies (1974)

- The Nettling of Harold (2001)

- Also by Alan Garner

- About the Publisher