- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Fontana History of Chemistry

About this book

The Fontana History of Chemistry, which draws extensively on both the author’s own original research and that of other scholars world wide, is conceived as a work of synthesis. Nothing like it has been attempted in decades.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Fontana History of Chemistry by William Brock in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Chemistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

On the Nature of the Universe and the Hermetic Museum

Maistryefull merveylous and Archimastrye Is the tincture of holy Alkimy;

A wonderful Science, secrete Philosophie,

A singular grace and gifte of th’Almightie:

Which never was found by labour of Mann,

But it by Teaching, or by Revalacion begann.

A wonderful Science, secrete Philosophie,

A singular grace and gifte of th’Almightie:

Which never was found by labour of Mann,

But it by Teaching, or by Revalacion begann.

(THOMAS NORTON, The Ordinall of Alchemy, c. 1477)

In 1477, having succeeded after years of study in preparing both the Great Red Elixir and the Elixir of Life, only to have them stolen from him, Thomas Norton of Bristol composed the lively early English poem, The Ordinall of Alchemy. Here he expounded in an orderly fashion the procedures to be adopted in the alchemical process, just as an Ordinal lists chronologically the order of the Church’s liturgy for the year. Unfortunately, although the reader learns much of would-be alchemists’ mistakes, and of the ingredients and apparatus, of the subtle and gross works, and of the financial backing, workers and astrological signs needed to conduct the ‘Great Work’ successfully, the secret of transmutation remains tantalisingly obscure.

The historian Herbert Butterfield once dismissed historians of alchemy as ‘tinctured with the kind of lunacy they set out to describe’; for this reason, he thought, it was impossible to discover the actual state of things alchemical. Nineteenth-century chemists were less embarrassed by the subject. Justus von Liebig, for example, used the following notes to open his Giessen lecture course:

Distinction between today’s method of investigating nature from that in olden times. History of chemistry, especially alchemy …

Liebig’s presumption, still widespread, was that alchemy was the precursor of chemistry and that modern chemistry arose from a rather dubious, if colourful, past1:

The most lively imagination is not capable of devising a thought which could have acted more powerfully and constantly on the minds and faculties of men, than that very idea of the Philosopher’s Stone. Without this idea, chemistry would not now stand in its present perfection …[for] in order to know that the Philosopher’s Stone did not really exist, it was indispensable that every substance accessible … should be observed and examined.

To most nineteenth-century chemists, and historians and novelists, alchemy had been a human aberration, and the task of the historian seemed to be to sift the wheat from the chaff and to discuss only those alchemical views (chiefly practical) that had contributed positively to the development of scientific chemistry. As one historiographer of the subject has put it2:

[the historian] merely split open the fruit to get the seeds, which were for him the only things of value. In the fruit as a whole, its shape, colour, and smell, he had no interest.

But what was alchemy? The familiar response is that it involved the pursuit of the transmutation of base metals such as lead into gold. In practice, the aims of the alchemist were often a good deal broader, and it is only because we take a false perspective in seeing chemistry as arising from alchemy that we normally narrowly focus on to alchemy’s concern with the transformation of metals. However, as Carl Jung pointed out in his study Psychology and Alchemy, there are similarities between the emblems, symbols and drawings used in European alchemy and the dreams of ordinary twentieth-century people. One does not have to believe in psychoanalysis or Jungism to see that the most obvious explanation for this is that alchemical activities were often concerned with a spiritual quest by humankind to make sense of the universe. It follows that alchemy could have taken different forms in different cultures at different times.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, after the elderly French chemist, Marcellin Berthelot, had made available French translations of a number of Greek alchemical texts, an American chemist, Arthur J. Hopkins (1864–1939), showed how they could be interpreted as practical procedures involving dyeing and a series of colour changes. He was able to show how Greek alchemists, influenced by Greek philosophy and the practical knowledge of dyers, metallurgists and pharmacists, had followed out three distinctive transmutation procedures, which involved either tincturing metals or alloys with gold (as described in the Leiden and Stockholm papyri), or chemically manipulating a ‘prime matter’ mixture of lead, tin, copper and iron through a series of black, white, yellow and purple stages (which Hopkins was able to replicate in the laboratory), or, as in the surviving fragments of Mary the Jewess, using sublimating sulphur to colour lead and copper.

While Hopkins’ explanation of alchemical procedures has formed the basis of all subsequent historical work on early alchemical texts, and while Jung’s psychological interpretation has stimulated interest in alchemical language and symbolism, it was the work of the historian of religion, Mircea Eliade (1907–86), who, following studies of contemporary metallurgical practices of primitive peoples in the 1920s, firmly placed alchemy in the context of anthropology and myth in Forgerons et Alchimistes (1956).

These three twentieth-century interpretations of alchemy, dyeing, psychological individuation and anthropology, together with the historical investigation of Chinese alchemy being undertaken by Joseph Needham and Nathan Sivin in the 1960s, stimulated the late Harry Sheppard to devise a broad definition of the nature of alchemy3:

Alchemy is a cosmic art by which parts of that cosmos – the mineral and animal parts – can be liberated from their temporal existence and attain states of perfection, gold in the case of minerals, and for humans, longevity, immortality, and finally redemption. Such transformations can be brought about on the one hand, by the use of a material substance such as ‘the philosopher’s stone’ or elixir, or, on the other hand, by revelatory knowledge or psychological enlightenment.

The merit of such a general definition is not only that it makes it clear that there were two kinds of alchemical activity, the exoteric or material and the esoteric or spiritual, which could be pursued separately or together, but that time was a significant element in alchemy’s practices and rituals. Both material and spiritual perfection take time to achieve or acquire, albeit the alchemist might discover methods whereby these temporal processes could be speeded up. As Ben Jonson’s Subtle says in The Alchemist, ‘The same we say of Lead and other Metals, which would be Gold, if they had the time.’ And in a final sense, the definition implies that, for the alchemist, the attainment of the goals of material, and/or spiritual, perfection will mean a release from time itself: materially through riches and the attainment of independence from worldly economic cares, and spiritually by the achievement of immortality.

The definition also helps us to understand the relationship between the alchemies of different cultures. Although some historians have looked for a singular, unique origin for alchemy, which then diffused geographically into other cultures, most historians now accept that alchemy arose in various (perhaps all?) early cultures. For example, all cultures that developed a metallurgy, whether in Siberia, Indonesia or Africa, appear to have developed mythologies that explained the presence of metals within the earth in terms of their generation and growth. Like embryos, metals grew in the womb of mother Nature. The work of the early metallurgical artisan had an obstetrical character, being accompanied by rituals that may well have had their parallel in those that accompanied childbirth. Such a model of universal origin need not rule out later linkages and influences. The idea of the elixir of life, for example, which is found prominently in Indian and Chinese alchemy, but not in Greek alchemy, was probably diffused to fourteenth-century Europe through Arabic alchemy. The biochemist and Sinologist, Joseph Needham, has called the belief and practice of using botanical, zoological, mineralogical and chemical knowledge to prepare drugs or elixirs ‘macrobiotics’, and has found considerable evidence that the Chinese were able to extract steroid preparations from urine.

Alongside macrobiotics, Needham has identified two other operational concepts found in alchemical practice throughout the world, aurifiction and aurifaction. Aurifiction, or gold-faking, which is the imitation of gold or other precious materials – whether as deliberate deception or not depending upon the circumstances (compare modern synthetic products) – is associated with technicians and artisans. Aurifaction, or gold-making, is ‘the belief that it is possible to make gold (or “a gold”, or an artificial “gold”) indistinguishable from or as good as (if not better than) natural gold, from other different substances’. This, Needham suggests, tended to be the conviction of natural philosophers rather than artisans. The former, coming from a different social class than the aurifictors, either knew nothing of the assaying tests for gold, or jewellery, or rejected their validity.

CHINESE ALCHEMY

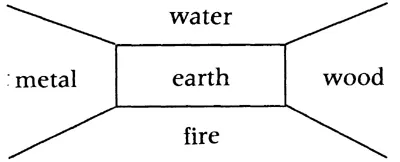

Aurifactional alchemical ideas and practices were prevalent as early as the fourth century BC in China and were greatly influenced by the Taoist religion and philosophy devised by Lao Tzu (c. 600 BC) and embodied in his Tao Te Ching (The Way of Life). Like the later Stoics, Taoism conceived the universe in terms of opposites: the male, positive, hot and light principle, ‘Yang’; and the female, negative, cool and dark principle, ‘Yin’. The struggle between these two forces generated the five elements, water, fire, earth, wood and metal, from which all things were made:

Unlike later Greco-Egyptian alchemy, however, the Chinese were far less concerned with preparing gold from inferior metals than in preparing ‘elixirs’ that would bring the human body into a state of perfection and harmony with the universe so that immortality was achieved. In Taoist theory this required the adjustment of the proportions of Yin and Yang in the body. This could be achieved practically by preparing elixirs from substances rich in Yang, such as red-blooded cinnabar (mercuric sulphide), gold and its salts, or jade. This doctrine led to careful empirical studies of chemical reactions, from which followed such useful discoveries as gunpowder – a reaction between Yin-rich saltpetre and Yang-rich sulphur – fermentation industries and medicines that, according to Needham, must have been rich in sexual hormones. As in western alchemy, Taoist alchemy soon became surrounded by ritual and was more of an esoteric discipline than a practical laboratory art.

Belief in the transformation of blood-like cinnabar into gold dates from 133 BC when Li Shao-chun appealed to the Emperor Wu Ti to support his investigations:

Summon spirits and you will be able to change cinnabar powder into yellow gold. With this yellow gold you may make vessels to eat and drink out of. You will increase your span of life, you will be able to see the hsien of the P’eng-lai [home of the Immortals] that is in the midst of the sea. Then you may perform the sacrifices fang and shang and escape death.

From then on, many Chinese texts referred to the consumption of potable gold. This wai tan form of alchemy, which was systematized by Ko Hung in the fourth century AD, was not, however, the only form of Chinese alchemy.

The Chinese also developed nai tan, or physiological, alchemy, in which longevity and immortality were sought not from the drinking of an external elixir, but from an ‘inner elixir’ provided by the human body itself. In principle, this was obtained from the adept’s own body by physiological techniques involving respiratory, gymnastic and sexual exercises. With the ever-increasing evidence of poisoning from wai tan alchemy, nai tan became popular from the sixth century AD, causing a diminution of laboratory practice. On the other hand, nai tan seems to have encouraged experimentation with body fluids such as urine, whose ritualistic use may have led to the Chinese isolation of sex hormones.

As Needham has observed, medicine and alchemy were always intimately connected in Chinese alchemy, a connection that is also found in Arabic alchemy. Since Greek alchemy laid far more stress on metallurgical practices – though the preparation of pharmaceutical remedies was also important – it seems highly probable that Arabic writers and experimentalists were ‘deeply influenced by Chinese ideas and discoveries’.

There is some evidence that the Chinese knew how to prepare dilute nitric acid. Whether this was prepared from saltpetre – a salt that is formed naturally in midden heaps – or whether saltpetre followed the discovery of nitric acid’s ability to dissolve other substances, is not known. Scholars have speculated that gunpowder – a mixture of saltpetre, charcoal and sulphur – was first discovered during attempts to prepare an elixir of immortality. At first used in fireworks, gunpowder was adapted for military use in the tenth century. Its formula had spread to Islamic Asia by the thirteenth century and was to stun the Europeans the following century. Gunpowder and fireworks were probably the two most important chemical contributions of Chinese alchemy, and vividly display the power of chemistry to do harm and good.

As in the Latin west, most of later Chinese alchemy was little more than chicanery, and most of the stories of alchemists’ misdeeds that are found in western literature have their literary parallels in China. Although the Jesuit missions, which arrived in China in 1582, brought with them information on western astronomy and natural philosophy, it was not until 1855 that western chemical ideas and practices were published in Chinese. A major change began in 1865 when the Kiangnan arsenal was established in Shanghai to manufacture western machinery. Within this arsenal a school of foreign languages was set up. Among the European translators was John Fryer (1839–1928), who devoted his life to translating English science texts into Chinese and to editing a popular science magazine, Ko Chih Hui Phien (Chinese Scientific and Industrial Magazine).

GREEK ALCHEMY

Although it is possible to argue that modern chemistry did not emerge until the eighteenth century, it has to be admitted that applied, or technical, chemistry is timeless and has prehistoric roots. There is conclusive evidence that copper was smelted in the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Ages (2200 to 700 BC) in Britain and Europe. Archaeologists recognize the existence of cultures that studied, and utilized and exploited, chemical phenomena. Once fire was controlled, there followed inevitably cookery (gastronomy, according to one writer, was the first science), the metallurgical arts, and the making of pottery, paints and perfumes. There is good evidence for the practice of these chemical arts in the writings of the Egyptian and Babylonian civilizations. The seven basic metals gave their names to the days of the week. Gold, silver, iron, mercury, tin, copper and lead were all well known to ancient peoples because they either occur naturally in the free state or can easily be isolated from minerals that contain them. For the same reason, sulphur (brimstone) and carbon (charcoal) were widely known and used, as were the pigments, orpiment and stibnite (sulphides of arsenic and antimony), salt and alum (potassium aluminium sulphate), which was used as a mordant for vegetable dyes and as an astringent.

The methods of these early technologists were, of course, handed down orally and by example. Our historical records begin only about 3000 BC. With the aid of techniqu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Preface to the Fontana History of Science

- Bibliographical Note

- Introduction

- 1: On the Nature of the Universe and the Hermetic Museum

- 2: The Sceptical Chymist

- 3: Elements of Chemistry

- 4: A New System of Chemical Philosophy

- 5: Instructions for the Analysis of Organic Bodies

- 6: Chemical Method

- 7: On the Constitution and Metamorphoses of Chemical Compounds

- 8: Chemistry Applied to Arts and Manufactures

- 9: Principles of Chemistry

- 10: On the Dissociation of Substances Dissolved in Water

- 11: How to Teach Chemistry

- 12: The Chemical News

- 13: The Nature of the Chemical Bond

- 14: Structure and Mechanism in Organic Chemistry

- 15: The Renaissance of Inorganic Chemistry

- 16: At the Sign of the Hexagon

- Epilogue

- Appendix: History of Chemistry Museums and Collections

- Notes

- Bibliographical Essay

- Index

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Other Books By

- Copyright

- About the Publisher