- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tales from the Special Forces Club

About this book

Stories of real-life bravery and courage-under-fire contribute to a unique and poignant record of a club created for heroes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tales from the Special Forces Club by Sean Rayment in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World War II. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

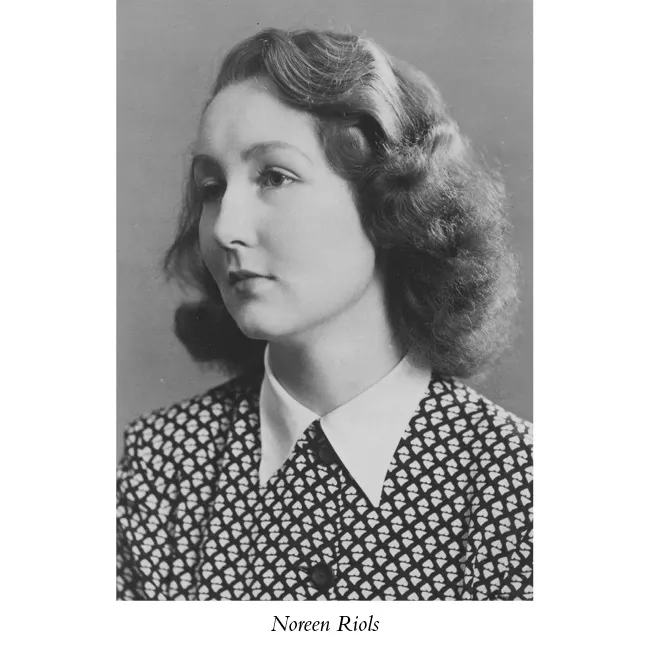

The Secret Life of Noreen Riols

Training SOE Agents

‘The disruption of enemy rail communications, the harassing of German road moves and the continual and increasing strain placed on German security services throughout occupied Europe by the organised forces of Resistance, played a very considerable part in our complete and final victory.’

General Eisenhower, May 1945

It was on a Monday morning in August 2011, when a black London taxi cab dropped me at the corner of a leafy crescent in Knightsbridge, that I made my first visit to the Special Forces Club as a guest of one of its original members.

The club is as anonymous today as it was when it opened after the Second World War, its address only known to a select few. I press a small bell fixed to the building’s outer wall adjacent to a heavy, tan-coloured oak door, and a few seconds later the door clicks open.

‘Yes, sir, can I help you?’ a young receptionist enquires helpfully.

‘My name is Sean Rayment and I’m here to see Noreen Riols,’ I respond. A few elderly club members milling around in the lobby immediately turn and look at me, with a mixture of suspicion and interest.

‘She is waiting for you through there,’ responds the receptionist, pointing at a half-open door through which the morning sun is starting to shine. As I walk past another office two middle-aged men look up from behind their computer and stare unsmiling as I pass. I feel as though I have just been frisked.

Looking into the room, I see that Noreen Riols is reclining in a slightly worn, red velvet armchair which has the effect of diminishing her delicate frame. She is sipping a cup of breakfast tea while reading a copy of The Times and appears perfectly at home in the cosy, peach-coloured drawing room.

‘Noreen?’ I ask hesitantly as I enter the room.

‘Yes?’ she replies, looking slightly confused before a smile fills her face. ‘You must be Sean. I’m sorry, I was expecting someone older. Please, come in and sit down. Now, would you like a cup of tea?’

After months of research, searching and seemingly endless emails and telephone calls, I have come face to face with Noreen Riols, one of the very few members of the SOE still alive.

As a journalist and former officer in the Parachute Regiment, I have met members of covert intelligence agencies, such as MI5, MI6, the SAS and more obscure organisations such as 14 Intelligence Company, which operated exclusively in Northern Ireland from the 1980s and whose existence was never officially acknowledged by the British government, on numerous occasions. I have always been struck by the physical ordinariness of those who inhabit the covert world. They might be super-fit and have brilliant analytical minds, but from the outside they tend not to stand out from the crowd; they are mostly neither too tall nor too short, fat or thin, handsome or ugly – just ordinary. For those who live their lives in the covert world of espionage and counter-espionage, blending in, being almost invisible within the crowd can be a life-saving quality. And Noreen is no exception. Sipping tea in the Special Forces Club she looked like everyone’s favourite granny, with a kind, smiling, gentle face. It was curious, therefore, to think that some 70 years earlier Noreen was one of a select band of SOE personnel who were training agents to conduct assassinations and sabotage across Europe as Britain and its allies fought for their very existence.

Noreen and I shake hands before she adds: ‘There aren’t very many of us left, you know.’ By that she means members of the SOE, the wartime clandestine force created in July 1940 on the orders of Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister, and Hugh Dalton, the Minister for Economic Warfare, with the aim of conducting sabotage, espionage, assassinations and forming resistance movements against the Axis powers in occupied countries.

Noreen was one of the many women employed by the secret organisation during the war. Today, aged 86, she is one of the few surviving members of F Section – the department which dispatched more than 400 agents, including 39 female spies, into France between 1941 and 1945. The methods of infiltration included parachuting, landing by aircraft and using fishing boats and submarines.

The section was one of SOE’s most successful and was responsible for creating dozens of underground networks across France. Many of the agents were Britons who were fluent in French and were recruited from a wide range of backgrounds and occupations. Some were already serving in the armed forces, while others were recruited because of their knowledge of France, all united by their loathing of the Nazi ideology and the desire to strike back at a regime which had already enslaved millions of civilians.

But it was a dangerous and demanding occupation, and newly trained agents were warned that they had a 50 per cent chance of surviving the war. Those who were captured faced torture at the hands of the Gestapo followed by almost certain execution.

SOE’s primary role was to help organise the French Resistance into a fighting force capable of mounting sabotage, with the primary targets being the rail and telephone networks.

‘Isn’t it funny that now that there are so few of us left we are in more demand than ever?’ Noreen adds before returning to her seat. ‘Now tell me, what do you want to know? There are no secrets any more.’

* * *

Noreen Riols was born into a naval family on the Mediterranean island of Malta. From an early age she had decided that she too wanted to lead an adventurous life which would begin with taking a degree at Oxford. War broke out before she was ready to go to university, but she was already becoming a capable linguist at the Lycée, the French school in South Kensington.

‘The Lycée was evacuated early in the war, but a few girls remained in one class and I was one of those – but I can’t remember doing any work at all and I seemed to spend the whole of my life tearing around South Kensington on the back of a Free French airman’s motorbike.

‘Life in London at that time was pretty dreadful because it was being bombed all the time and people were being killed, as you would expect, but I don’t think we, girls of my age, ever realised how much danger we were in.

‘I remember being in the Lycée when it was bombed in 1941. The school had been occupied by the Free French Air Force, and one day I heard a plane coming over and I’d just looked out of the window very excitedly when suddenly a French airman leapt on top of me and both of us were flat on the floor. Seconds later the bomb exploded and the window came crashing in. If he hadn’t knocked me to the floor I would have been seriously injured or worse. That’s why I say I don’t think we really had any appreciation of the danger we faced daily. I don’t ever remember being frightened – I don’t think you do get frightened when you are young.’

‘I got my call-up papers when I was 18. The papers said that either you joined the armed forces or you go and work in a munitions factory, but the idea of working in a munitions factory did not appeal to me in the slightest.

‘All of my friends knew that we were going to be called up when we reached 18, and I thought I’ll follow in my father’s footsteps and I’ll become a member of the Women’s Royal Naval Service, WRNS. I thought the hat was very stylish and I could see myself in the uniform. But when I went to join up I was told that the only vacancies for women in the Royal Navy were for cooks and stewards, and the idea of making stew or suet pudding for the rest of the war was not the Mati Hari image I wanted to give to the waiting world, so I declined.

‘My instructions were to report to a Labour Office somewhere in west London and when I was told by the female clerk behind the counter what my options were I said, “I’m not doing that or that,” and frankly this woman wasn’t having any of it, she got a bit ratty and said, “Make up your mind – it’s this or that, and if you can’t make up your mind I’ll put you down for a factory.”

‘Well, you can imagine how I felt, and I started to cause a bit of a fuss and said, “I will not work in a factory,” and stamped my feet and so on. At which point a door opened and a slightly irritated man looked out and said: “OK, I’ll take over this one.” He then proceeded to ask me a lot of questions which had nothing to do with the warship I intended to take charge of.

‘He then picked up on my schooling and said, “I see you went to the Lycée. You speak French?” I said yes, and then he started speaking to me in several different languages. He was leaping about from one to another like a demented kangaroo and he seemed quite surprised that I could keep up with him in French, German and Spanish. After the interview he sent me to the Foreign Office, where I was ushered into a windowless room, where again I was questioned by a high-ranking officer. Of course I had no idea what I was being interviewed for at that stage, but looking back I think there was obviously some kind of liaison between the Lycée, the SOE and the Labour Office. At that stage there was a requirement for people who could speak languages to carry out secret work – but it’s not the sort of thing you can advertise for.

‘After that interview I ended up at 64 Baker Street, the headquarters of SOE, but I had no idea where I was or what the building was for or the work they were doing. It was at Baker Street that I met Colonel Maurice Buckmaster, who was a major then and was in charge of SOE’s French section.’

The SOE recruited people from all walks of life, with the primary requirement being a thorough knowledge of the country in which the agent was to operate. Fluency in the native language was vital, especially French for those entering France; thus exiled or escaped members of the armed forces of various occupied countries proved to be a fertile recruiting ground. Agents needed to be both ruthless and diplomatic, callous enough to slit a man’s throat or execute an informer, while also able to master the politics of, say, the French Resistance movement and motivate members of it accordingly. Training was tough and, as we shall see later in the chapter, trainees could be failed at any stage.

While Baker Street was the main headquarters, the organisation’s various branches and departments were strewn across London and much of England. Wireless production and research departments were based in Watford, Wembley and Birmingham. The camouflage, make-up and photography sections, Stations XVa, XVb and XVc, were largely based in the Kensington area of west London. Station XVb, a camouflage training base and briefing centre, was located in the Natural History Museum. In addition to the various stations there were over 60 separate training centres across Britain, where agents would be taught a wide variety of field skills, including demolition, sabotage and assassination techniques.

Station XV – The Thatched Barn – was one of the most important establishments within the SOE. It was a two-storey mock-Tudor hotel built in the 1930s in Borehamwood, Hertfordshire, and had been acquired by Billy Butlin, the holiday camp entrepreneur, before being requisitioned by SOE.

The Thatched Barn was the place where agents would be kitted out with clothing and equipment which was appropriate for the country in which they were about to infiltrate. Every item of clothing had to be an exact fit with what was expected for that particular country, or even region. So if the French in Brittany, say, stitched hems in a particular way, then that method needed to be used when fitting clothes for an agent about to be sent to that region. Nothing could be left to chance.

‘At the time the headquarters was called the Inter-Allied Research Bureau – well, that meant absolutely nothing to me, as you can imagine. I was hopping from one office to the other. Buck sent me to another office and said this captain is expecting you – and he may have been, but by the time I’d got there he’d forgotten that he was meant to be interviewing me. He looked at me as though I had walked in from outer space and then said, “Nobody, but nobody must know what you do here. That includes brothers, sisters, aunts, uncles.” Then an immensely tall man called Eddie McGuire, an Irish Guards officer, shot into the room making very funny, squeaky sounds. It really was quite a bizarre scene. Then the two of them suddenly stopped talking and ran out of the room and down the corridor. I wondered where I was – I was only just 18 at the time and it felt like I was in a lunatic asylum being run by the Crazy Gang.

‘I looked down the corridor and I could see that all the doors were open and people were running around. I learnt later that these two men had just returned from the field and were a bit on edge, and Eddie had been shot in the throat while escaping, which is why he spoke like a ventriloquist’s doll.

‘There was a FANY* inside the room who seemed to be completely unperturbed by everything that was going on, so I said to her, “Is it always like this here?” and she said, “Oh no, it’s usually much worse, but don’t worry, you’ll get used to it,” and I did.

‘After that interview, I was in, although I didn’t really know what I was in. I only knew that I was involved in something secret, because I kept being told not to reveal anything about what went on and not to ask questions. The view then, and it holds true today, is that the less you know, the less you can reveal, and if the worst happens, and the worst was of course a German invasion, then the less you could reveal under interrogation. I didn’t know it at the time but everyone who worked for SOE was on the Gestapo’s hit list.’

The interview was concluded and Noreen was asked if she could begin work immediately – by which she thought they meant the following morning, but inside the SOE immediately meant immediately. Within the hour she was ensconced inside an office in Montague Mansions, another building taken over by SOE as it grew almost daily, a few streets away from the Baker Street headquarters.

‘I was a bit of a runaround at first, until I got to know how things worked. One of my first jobs was to ensure that special coded messages which were broadcast every evening by the BBC at Bush House were in the right place at the right time. That meant taking them down to the “Basement”, as it was known somewhat sinisterly, which was run by a sergeant who was a veteran of the First World War. He wasn’t a particularly happy person and he seemed to have a cigarette permanently glued to his top lip, but we seemed to get on after a while.

‘Probably my most important job at that time was to get all the messages from all the various sections to him by 5pm, so that they could be sent over to the BBC – it was crucial that the messages went out so that the Resistance units could get their instructions.’

Noreen was working alongside living legends of the secret world such as Leo Marks, a cryptographer in charge of agent codes, and Forest Yeo-Thomas, codename the White Rabbit, one of the organisation’s most celebrated agents. The two men were great friends, according to Noreen.

‘Leo Marks’s office was on the ground floor and mine was on the first floor but I saw a lot of him. He was a very nice chap, but his popularity was further increased because his mother was always sending him cakes, biscuits and freshly made sandwiches, which, because he was so nice, he always shared with other people so there was always a bit of a party taking place in his room.

‘After a few months I was given better and more interesting jobs, and one of the most interesting was to attend agent debriefing sessions. There was a fairly straightforward routine when an agent came in. First of all they were given a huge cooked breakfast at the airport, after which they were taken to a place called Orchard Court, in Portman Square, close to the SOE headquarters. It could sometimes take months to get an agent back from the field for a debriefing session because of the complexities of living in occupied France. It was about at that stage that I really began to understand the sort of pressures the agents were under.

‘It was always fascinating to see them just hours after they had left France. Some would be shaking and chain smoking, and others who had witnessed or suffered much worse experiences were as cool as cucumbers. I think it was awfully easy for a lot of people in England to say at the time, “I’d never talk if I was captured.” But when you are actually over there none of us could tell what our reactions would be, and I suppose a time would come when the human spirit can no longer take any more punishment.

‘The debriefing sessions were very relaxed, the agents were never rushed or pushed too hard, but the interviews were very detailed and could last several hours because the agents had so much information.

‘A wireless operator for example was under enormous pressure, because he would have only about 15 minutes to send his message, which had to contain a lot of information about sabotage or enemy movements, but other information couldn’t be included because it wasn’t as crucial as operations.

‘The idea of the debriefing sessions was to get into the real detail, such as the need to have a permit to put a bike on a train, or indeed the need for more bikes. The information was often the sort of detail a radio operator wouldn’t be able to send because the need wasn’t urgent. Every little bit of information helped in the preparation and briefing of agents who were just about to deploy on an operation. All of the agents had to be 100 per cent convincing all of the time, and it might be very small, almost insignificant details such as only being able to have coffee twice a week – that little bit of detail could be really important for a new agent going into an occupied country. Just imagine a new agent being lifted by the police and being asked a simple question like “How many cups of coffee do you drink a week?” The wrong answer could be a death sentence.’

By the middle of 1943 Noreen was a fully-fledged member of the SOE. She would begin work every morning, dressed in civilian clothes, at around 8am and work through until 6pm or later, depending on whether there was some sort of emergency. It became second nature never to talk about her work, and even her own mother was convinced Noreen was a secretary in the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. With her almost perfect French, Noreen worked exclusively in F Section, the department which looked after agents in France. SOE now occupied several buildings in central London, all close to the headquarters in Baker Street. Working in the headquarters were citizens of every country occupied by the Axis powers – but there was, according to Noreen, an unwritten rule, which was that there could be absolutely no contact between people from the different sections for security reasons.

‘We were all very aware that the agents’ security, their lives in fact...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- In Memory

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 The Secret Life of Noreen Riols

- 2 The Two Wars of Jimmy Patch

- 3 The Greatest Raid of All

- 4 ‘The Best Navigator in the Western Desert’

- 5 Popski’s Private Army

- 6 The Moonlight Squadrons

- 7 Jungle Warfare behind Enemy Lines

- 8 The Jedburgh Teams

- 9 ‘We weren’t bloody playing cricket’

- 10 A Radio Operator at War

- Acknowledgements

- Picture Section

- Copyright

- About the Publisher