![]()

Appendix 1: Key People

The Three Kings

King George V of Britain, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, and Tsar Nicholas II of Russia (Georgie, Willy and Nicky) were all cousins. George and Wilhelm were both grandsons of Queen Victoria and Nicholas’ wife, the Empress Alexandra, was her granddaughter. They met, as a threesome, only twice. All three were considered feckless.

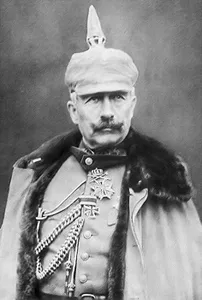

Kaiser Wilhelm II

Arrogant, extremely vain, and always seeking praise, Wilhelm II enjoyed a life of frivolity. His former chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, once remarked that the Kaiser would have liked every day to be his birthday. Much to Wilhelm’s delight, Queen Victoria made her grandson an honorary admiral of the Royal Navy for which, he said, he would always take an interest in Britain’s fleet as if it was his own. Born with a paralyzed left arm, considerably shorter than the right, Wilhelm needed help with eating and dressing throughout his life, and went to great lengths to hide his disability.

Kaiser Wilhelm II, c. 1918

A lover of all things military and a collector of uniforms (he owned 600, many he designed himself), Wilhelm’s knowledge of military matters was little more than that of an overenthusiastic schoolchild. During the war, his ministers and generals bypassed him, and Ludendorff, especially, became a de facto ruler of the country.

Following the war and his forced abdication, Wilhelm lived in exile in the Netherlands. His cousin, King George, described him as ‘the greatest criminal in history’. The Dutch queen, Queen Wilhelmina, declined ever to meet the fallen Kaiser but when the Paris Peace Conference requested Wilhelm’s extradition to face trial for war crimes, she refused.

In 1940, with Hitler’s armies bearing down on the Netherlands, the Dutch royal family fled to Britain. Wilhelm however did not, even refusing Winston Churchill’s offer of asylum. He preferred instead to live under German occupation, hoping that the Nazis would restore the monarchy. He died the following year.

Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II believed he ruled Russia by divine right and could see no other way but rule by autocracy. He paid little heed to either his advisors or his people, and ignored the political and social unrest fermenting in Russia. That he was despised and considered an anachronism had no effect on the Tsar. No believer in change, he undid the minor reforms he felt obliged to implement following the failed Russian Revolution of 1905.

Tsar Nicholas II, 1909

George Grantham Bain collection, Library of Congress

Following Russian reversals during the early stages of the First World War, he took personal command of Russia’s military, despite having no experience of military matters. It was a fatal error of judgement – because he could no longer blame his generals for the failure of Russia’s armies, defeat was now his personal responsibility. He left the running of the country to his wife, Alexandra, who, in turn, was overly influenced by the mercurial monk, Georgi Rasputin. This, together with the growing disillusionment of war, did nothing to help the Tsar’s cause.

Forced to abdicate in March 1917, following the February Revolution, Nicholas and his family and immediate entourage were imprisoned and held in various safe houses. The British government wanted to offer Nicholas asylum but King George, his cousin, refused it, fearing that the presence of the fallen Tsar in Britain could cause trouble.

On the night of 18 July 1918, they were all shot by the Bolsheviks, probably on the order of Lenin.

King George V

When, in 1917, King George V changed the family name from Saxe-Coburg-Gotha to Windsor, his cousin, Wilhelm II, joked, ‘I look forward to seeing the Merry Wives of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha’. George preferred shooting and stamp collecting than being in the company of politicians or intellectuals. Nor were politicians and intellectuals terribly impressed by the King. During his coronation in 1911, the English writer and caricaturist, Max Beerbohm, dismissed the King as ‘such a piteous, good, feeble, heroic little figure’. And David Lloyd George, on first meeting him, said, ‘The King is a very jolly chap . . . thank God there is not much in his head’.

King George V, 1923

George Grantham Bain collection, Library of Congress

Of the three cousins, George wielded the least power but consequently was the only one to survive in post. He died in 1936 to be succeeded by Edward VIII.

Horatio Kitchener 1850–1916

Lord Kitchener’s face and pointing finger proclaiming ‘Your country needs you’, often copied and mimicked, is one of the most recognizable posters of all time.

Born in County Kerry, Ireland, Kitchener first saw active service with the French army during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 and, a decade later, with the British Army during the occupation of Egypt. He was part of the force that tried, unsuccessfully, to relieve General Charles Gordon, besieged in Khartoum in 1885. The death of Gordon, at the hands of Mahdist forces, caused great anguish in Britain. As commander-in-chief of the Egyptian army, Kitchener led the campaign of reprisal into the Sudan, defeating the Mahdists at the Battle of Omdurman and reoccupying Khartoum in 1898. Kitchener had restored Britain’s pride.

Horatio Kitchener, 1914

Harris & Ewing collection, Library of Congress

His reputation took a dent however during the Second Boer War in South Africa, 1899–1902. Succeeding Lord Roberts as commander-in-chief, Kitchener resorted to a scorched-earth policy in order to defeat the guerrilla tactics of the Boers. Controversially, he also set up a system of concentration camps and interned Boer women and children and black Africans. Overcrowded, lacking hygiene and malnourished, over 25,000 were to die, for which Kitchener was heavily criticized.

The criticism however, did not damage Kitchener’s career. He became commander-in-chief of India, was promoted to field marshal, and, in 1911, Consul-General of Egypt, responsible, in effect, for governing the whole country.

At the outbreak of hostilities in 1914, Kitchener was appointed Secretary of State for War, the first soldier to hold the post, serving under Asquith’s Liberal government. Bleakly, he predicted a long war, a lone voice among the government and military elite, for which Britain would need an army far larger than the existing 1914 professional army, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). So Kitchener spearheaded a recruitment drive, appearing himself on the iconic poster. Hugely successful, Kitchener’s campaign recruited three million volunteers.

Popular with the public but less so with the government, the failure of the Gallipoli campaign saw Kitchener’s prestige fall. In June 1916, Kitchener was sent on a diplomatic mission to Russia aboard the HMS Hampshire. On 5 June, the ship hit a German mine off the Orkney Islands and sunk. Kitchener’s body was never found, leading to several conspiracy theories that he had become too much of an embarrassment and liability, and had been assassinated. David Lloyd George, then Minister for Munitions, was supposed to have been accompanying Kitchener but cancelled at the last minute – this merely added to the speculation.

Winston Churchill 1874–1965

Churchill admitted in 1915 to enjoying the war – in a letter to Lloyd George’s daughter, he wrote, ‘I know it’s smashing and shattering the lives of thousands every moment, and yet, I can’t help it, I enjoy every second of it’.

Academically weak, Churchill sought a career in the army, but took three attempts to pass the entrance exam for the Royal Military College in Sandhurst. In 1896, he served briefly on India’s North-West Frontier, writing up his experiences in a series of dispatches that brought him much attention. Churchill served as a cavalry officer during Lord Kitchener’s retaliatory campaign in the Sudan and took part in one of the last cavalry charges during the Battle of Omdurman in 1898.

Winston Churchill, 1904

IWM Collections, NYP 45063

In 1899, Churchill went to South Africa during the Second Boer War working as a correspondent for The Morning Post, but was captured by the Boers and interned in a prisoner-of-war camp. Following a daring escape, he later joined the British Army on its way to relieve the British garrison besieged in the city of Ladysmith.

Churchill became a politician in 1900, serving as a Conservative Member of Parliament before swapping sides and joining the Liberal Party in 1904. He served for a year as Home Secretary during which time he became an advocate for eugenics, proposing compulsory sterilization for the ‘feeble-minded’ and separate labour camps for ‘tramps and wastrels’.

In 1911, Churchill was appointed the First Lord of the Admiralty. Continuing the policy established by his predecessor, Churchill, determined to keep Britain ahead of the Germans, expanded the navy by introducing Dreadnoughts, the most powerful battleships of the time.

Throughout the war, Churchill furthered the cause of the newly developed ‘landships’, or tanks. It was in his capacity within the Admiralty, that Churchill canvassed a navy-only assault on the Dardanelles. Its failure to deliver, and the consequent disaster of Gallipoli, was a severe setback to Churchill’s reputation. Demoted and demoralized, Churchill handed in his resignation from the coalition government and, although he remained an MP, joined the front-line troops as a lieutenant colonel on the Western Front. By all accounts, he was popular and courageous and ventured thirty times or so into No Man’s Land.

After four months in France, Churchill returned to London and within a couple of months, despite Conservative protests, was appointed Minister for Munitions.

Following the war, in January 1919, Churchill became Secretary of State for War, and, deeply alarmed by the Bolshevik threat, poured more troops to fight the counter-revolutionary cause during the Russian Civil War.

Losing his seat as a Liberal MP, Churchill again swapped sides and served a Conservative government as Chancellor of the Exchequer until their defeat in the election of 1929. Although the Conservatives were re-elected in 1931, Churchill, considered too much a loose cannon, was sidelined. He remained in the shadows throughout the thirties, writing and painting, until recalled to the Admiralty in 1939, by which time the Second World War had begun.

Douglas Haig 1861–1928

Born in Edinburgh, Haig, an expert horseman, once represented England at polo. In 1898, he joined Kitchener’s force in the Sudan. Asked by Kitchener’s superiors in London to report back in confidence on his commander, Haig did so with relish, taking delight in criticizing the unsuspecting Kitchen...