- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

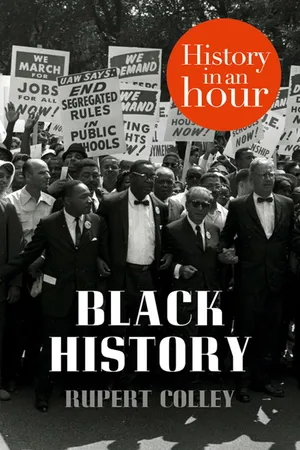

Black History: History in an Hour

About this book

Love history? Know your stuff with History in an Hour.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Black History: History in an Hour by Rupert Colley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire de l'Afrique. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoireSubtopic

Histoire de l'AfriqueThe Civil Rights Movement 1:

‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere’

‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere’

In May 1954, following the Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas case, the US Supreme Court ruled that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional. Oliver Brown, a father of a school-aged child, challenged the law that stated he had to send his daughter to an all-black school much further away than the local, all-white school. The Supreme Court agreed and concluded: ‘In the field of public education the doctrine of “separate but equal” has no place’, referring to and overturning the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson case. But with no fixed timetable, and with the Southern states in no hurry to implement the ruling, the court was obliged to follow up a year later with an order that schools must integrate ‘with all deliberate speed’. School buses transported school children considerable distances to ensure integration and fifteen years later, in 1969, the Supreme Court had to intervene again when many schools had still to desegregate.

In August 1955, a fourteen-year-old black boy, Emmett Till, was mutilated and murdered by white racists in Mississippi. His crime – ‘disrespecting’ a white woman. His killers were controversially found not guilty by a white jury. Later, safe from retrial on the double jeopardy ruling, the killers admitted their guilt and sold their stories to the press, much to national outrage.

On 1 December 1955, in Montgomery, Alabama, 42-year-old Rosa Parks, seated in a segregated bus, refused to give up her seat to a white man. The bus driver called the police and Parks (pictured below) was arrested. Parks was the local secretary of NAACP and the branch had been looking for an opportunity to stage a boycott of the city’s buses. The opportunity now presented itself and the boycott duly started on 5 December. The Montgomery boycott was led by a 26-year-old recently appointed Baptist Reverend by the name of Martin Luther King Junior.

Rosa Parks, c.1955 with Martin Luther King in the background

Lasting a year, the boycott caused much hardship and inconvenience, but eventually the city’s buses, so reliant on its black customers, relented. In November 1956, the Supreme Court declared segregation on public transport to be illegal and a month later, on 21 December, stepping on board the first non-segregated bus in Montgomery was the Reverend King.

Inspired by the non-confrontational approach adopted by Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr spoke for the rising black consciousness of 1950s America. ‘The objective,’ said King, ‘was not to coerce but to correct; not to break bodies or wills but to move hearts.’

In September 1957, nine black students tried to enrol at the recently desegregated Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. The state governor ordered in the Arkansas National Guard to keep them out. Finally, after three weeks of picketing and escalating tensions, President Eisenhower dispatched Federal troops to escort the ‘Little Rock Nine’ to class. Televised throughout America, it showed the stark reality of racial injustice still prevalent within the country’s borders.

However, Eisenhower’s attitude towards civil rights was lukewarm at best, and one month before the 1960 presidential election it was his Democratic opponent who stole the lead on civil rights. During a sit-in in Atlanta, King was arrested and sentenced to four months’ hard labour. It was John F. Kennedy who rang King’s wife and his brother, Robert F. Kennedy, who pulled the strings and had King’s sentence reversed, not Eisenhower. With the black vote now in his favour, Kennedy went on to win the election of November 1960.

Black students throughout the South extended their non-violent protests by organizing further sit-ins. In February 1960, four students in Greensboro, North Carolina were denied service in a segregated diner. Refusing to leave, they were threatened and insulted, but determined they should be served, they returned the following day, and again throughout the week. Students, both black and white, joined their protest, prepared to sit in dignified silence whilst mobs jeered, poked and smeared ketchup and mustard in their hair. But the protests continued, rapidly spreading across the South, affecting restaurants, hotels, shops, libraries, beaches and most public facilities. Television cameras tracked the story as the tension escalated, and families throughout America and abroad watched with horror the unfolding indignities and intimidation happening in the land of the free.

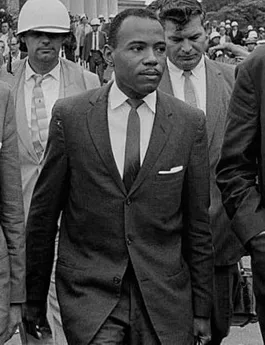

James Meredith, University of Mississippi, 1962

Photograph by Marion S. Trikosko, US News & World Report

Photograph by Marion S. Trikosko, US News & World Report

In 1962, Kennedy had to order troops to assist James Meredith (pictured above), a young black man, enrol at the University of Mississippi. In September, the governor of Mississippi, Ross Barnett, physically blocked Meredith’s entrance to the university. The following month, Meredith tried again, this time with the aid of Kennedy’s Federal enforcement. The ensuing riots saw two killed and over a hundred and sixty injured. Meredith finally took his place, and having suffered a year of racism and intimidation, graduated in August 1963 with a degree in political science.

Whilst state-run segregated buses had been declared illegal, inter-state bus facilities remained segregated. In May 1961, protestors embarked on the Freedom Rides, organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). They were met with civil disturbances and violence throughout the South as white mobs attacked the buses. In Montgomery the governor of Alabama refused to send the State Guard to protect the passengers and Robert F. Kennedy had to order in Federal troops to break up the increasingly violent scenes. But finally, effective from 1 November 1961, inter-state bus services were desegregated.

In May 1963, Birmingham, Alabama saw a major protest against the city’s segregation policies. The city’s police used dogs and fire hoses against the peaceful demonstrators, which included women and children. Nearly 3,000 people were arrested, amongst them King, his thirteenth arrest. From his cell, King used scrap pieces of paper and margins of newspapers to write a 7,000-word open letter on the moral issues of the civil rights movement. Known as the Letter from Birmingham Jail, it included the line, ‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.’

On 11 June 1963, President Kennedy spoke on national television about the need for civil rights: ‘Legislation cannot solve this problem alone. It must be solved in the home of every American.’ Within a few days, Kennedy had presented Congress with a sweeping raft of civil rights legislation, which despite its moral necessity required greater Federal power at the expense of state power. It was perhaps asking too much. Civil rights leaders, realizing the potential for its failure, decided, against Kennedy’s advice, to organize a huge demonstration to pressurize Congress into passing the bill.

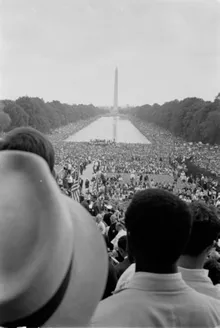

Two hundred and fifty thousand protestors on the March on Washington, August 1963

Photograph by Warren K. Leffler, US News & World Report Magazine

Photograph by Warren K. Leffler, US News & World Report Magazine

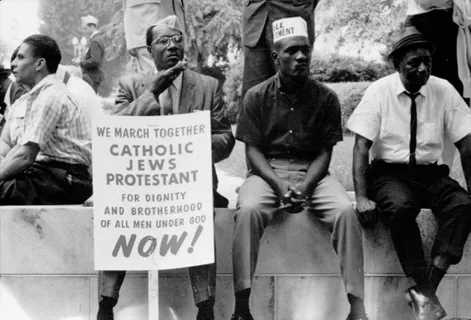

On 28 August 1963, 250,000 people took part in the ‘March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom’. On the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, folk singer Joan Baez led the crowd in the song that had become the anthem of the civil rights movement, ‘We Shall Overcome’, and Bob Dylan sang ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’. The marchers, black and white, young and old, rich and poor, a complete cross section of society, listened as Martin Luther King proclaimed, ‘I have a dream … I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at a table of brotherhood … I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character. ’

A mere month later, in Birmingham, Alabama, four white supremacists detonated a bomb at a Baptist church popular with African-Americans. Twenty people were injured in the explosion and four young girls, aged eleven to fourteen, were tragically killed. After a series of bungled investigations into the Birmingham Church Bombing, involving blocked evidence and malpractices, the last of the four killers was finally convicted in 2002. It had taken almost four decades for justice to be done.

On 22 November 1963, Kennedy was assassinated. Lyndon B. Johnson, appointed his successor, prioritized the Civil Rights Bill, which was passed on 2 July 1964. Segregation in public facilities was now illegal, as was to discriminate on the basis of race, colour, religion or country of origin.

The Civil Rights Movement 2:

‘Burn, burn, burn’

‘Burn, burn, burn’

Whilst the ending of segregation was a huge achievement, the Southern states still managed, through intimidation and violence, to deny black people the vote and education. The civil rights movement had reinvigorated the Ku Klux Klan, especially in Mississippi, the poorest of the Southern states. During the summer of 1964, CORE targeted Mississippi in a campaign to increase the number of black people registered to vote, and to help run ‘freedom schools’. Attracting almost 1,000 volunteers, black and white, they were met with violence and intimidation culminating in the disappearance of three friends, two white youths and their black companion. When their bodies were found six weeks later in the Mississippi, their murders caused a national outrage.

Protestors on the Selma to Montgomery march, March 1965

Photograph by Peter Pettus (Library of Congress)

Photograph by Peter Pettus (Library of Congress)

On 7 March 1965, King, who had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize the previous year, its youngest recipient at that point, led 600 demonstrators on an 80-kilometre march from the Alabama town of Selma to the state capital of Montgomery; its objective to highlight the issue of black voting. But Alabaman police, mounted on horseback and armed with clubs and tear gas, attacked the marchers. Televised across America, the nation had again reason to feel sickened by the actions of its fellow countrymen. President Johnson, describing it as ‘an American tragedy’, placed the Alabama National Guard under Federal control and ordered it to protect the demonstration. King led 2,500 people in a second much shorter march two days later.

The full march on to Montgomery recommenced on 21 March, and on reaching its destination five days later, and following King’s emotional speech, the demonstrators sang the civil rights anthem, ‘We Shall Overcome’, the words modified to ‘We Have Overcome’.

President Johnson and Martin Luther King at the ceremony for the signing of the Voting Rights Act, 1965

Photograph by Yoichi R. Okamoto

Photograph by Yoichi R. Okamoto

Five months later, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act. The unscrupulous practices that had prevented African-Americans from voting, such as literacy tests and poll taxes, were banned. In signing the bill, President Joh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- About History in an Hour

- Contents

- Introduction

- Slavery: The ‘Peculiar Institution’

- The Black Slave: Three-Fifths the Man

- North and South: ‘If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong’

- War and Emancipation: ‘Previous condition of servitude’

- The Jim Crow Era: ‘Separate but equal’

- War, Migration and Depression: ‘Black is beautiful’

- War and Windrush: ‘To secure these rights’

- The Civil Rights Movement 1: ‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere’

- The Civil Rights Movement 2: ‘Burn, burn, burn’

- Black Power: ‘We gonna stop them white men from whuppin’ us’

- Britain and South Africa: ‘Rivers of blood’

- Forty Years later: ‘Because of the color of her skin’

- Appendix 1: Key Players

- Appendix 2: Timeline of Black History

- Copyright

- Got Another Hour?

- About the Publisher