- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

‘Never for me the lowered banner, never the last endeavour’ SIR ERNEST SHACKLETON

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Shackleton's Epic by Tim Jarvis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

SOUTH

Point Wild, the place Shackleton’s twenty-two men would call home for four months, complete with characteristic brash ice.

Courtesy of Tim Jarvis

Courtesy of Tim Jarvis

The trails of the world be countless,

and most of the trails be tried;

You tread on the heels of the many,

till you come where the ways divide;

And one lies safe in the sunlight,

and the other is dreary and wan,

Yet you look aslant at the Lone Trail,

and the Lone Trail lures you on.

and most of the trails be tried;

You tread on the heels of the many,

till you come where the ways divide;

And one lies safe in the sunlight,

and the other is dreary and wan,

Yet you look aslant at the Lone Trail,

and the Lone Trail lures you on.

Robert Service, The Lone Trail

In times of trouble pray God for Shackleton.

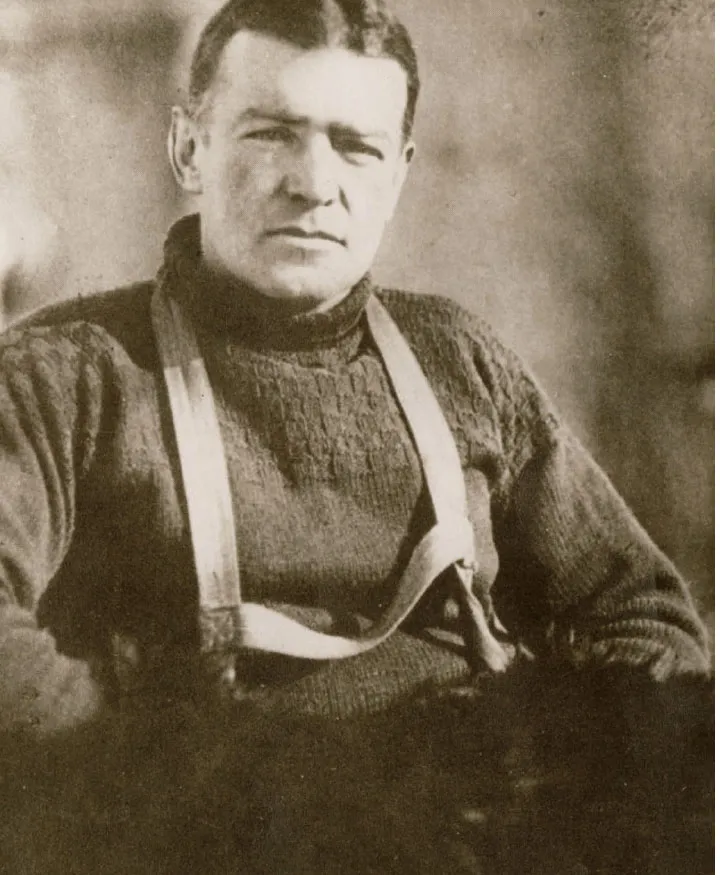

Photographs from the Collection of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG)

Photographs from the Collection of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG)

I thought I knew Antarctica by now. I had been to its frozen alien shores, a world with no native human population, three times. I had become, to the extent that one can, “used” to the highest, coldest, windiest continent in the world with its extreme weather and the staggering, kilometers-thick mantle of ice that covers it.

My initial expedition into the polar regions had been a trek of tortuous slowness across the island of Spitsbergen in the high Arctic with my close friend Andrew “Ed” Edwards, where the danger of polar bear attacks and crevasses challenged us to our limits and revealed a strength and determination I wasn’t aware I possessed. In 1999 I’d taken on what many regard as one of the last great land-based challenges on earth—crossing the continent’s 2,700 kilometers on foot and unsupported, pulling a sled weighing 225 kilograms through obstructive icy terrain. Among other consequences, I’d seen my fingers blackened by frostbite; experienced temperatures so low that three of my metal fillings contracted and fell out, requiring self-administered dental repairs; lost 20 percent of my body weight; eaten a sickness-inducing 7,200 calories of lard and olive oil each day; and written “That was the toughest day of my life” in my diary on seventeen consecutive days. On that occasion, my journey ended early, when a ruptured fuel container resulted in food contamination. Nevertheless, I had covered 1,800 kilometers and reached the Pole in a record forty-seven days, allowing even someone as self-critical as me to be rightly proud of what had been achieved.

Fate played its hand in my next journey, which was south to the Antarctic. For my work as a scientist I had moved to Adelaide in South Australia. This brought me into unlikely contact with the legacy of Australia’s greatest land-based polar explorer and an Adelaide legend, Sir Douglas Mawson.

In 1913 Mawson was forced to undertake an incredible survival journey. While mapping an uncharted section of the Antarctic coast as part of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, he lost the first of his two companions, Belgrave Ninnis, and the dog sled that contained most of the expedition’s food and equipment in a crevasse fall. What followed was starvation, blizzards, debilitating cold, and, ultimately, following the consumption of the remaining sled dogs, the death, in Mawson’s arms, of his second companion, Xavier Mertz, of what he described at the time as “fever.” Alone, Mawson faced ferocious winds, near-fatal crevasse falls, and terrible debilitation, all compounded by the loneliness and danger of solo travel. When, against all odds, he finally stumbled through the door of his hut fifty days later, his men asked, “Which one are you?” Mawson’s shocking physical state made him unrecognizable. With some having accused Mawson of cannibalizing Mertz in order to survive, I decided I would re-enact the journey with what he said he had available to him, not only to test myself but also to see if I could shed light on Mawson’s survival. When I returned to civilization, journey complete, I was asked for a word that described the hardship of surviving on my own on starvation rations in a frozen, reindeer-skin sleeping bag following the “death” of my colleague. All I could think of was “desperate.”

But this time I was planning a very different journey. In attempting to re-create Sir Ernest Shackleton’s legendary Antarctic survival trek across sea and ice in 1916, I would trade pulling a sled through mountains toward an endless white horizon for sailing and rowing a tiny, unstable wooden boat toward an endless gray one. Antarctica would be my starting point rather than my final destination. And I would be on a journey where the Antarctic weather that raged all around us would not only threaten from above but also turn the ocean across which we traveled into a tortured, ever-changing landscape of terrifying proportions.

The prospect of what lay ahead haunted me. Try as I might, I could not shake the image of a man in the dark water facing certain death, alone, watching his boat drift into the distance as the merciless cold of the Southern Ocean drained his lifeblood. Many thought the trip was virtually impossible. As he set off in his tiny, keel-less boat to try to cross the Southern Ocean from Elephant Island to South Georgia, Shackleton had said to his skipper, Frank Worsley, “Do you know I know nothing about boat sailing?” Worsley assured him that, luckily, he did. Shackleton was as usual being self-effacing about his ability. I, on the other hand, was not: I knew very little about boat sailing and in my darkest moments it weighed heavily on me.

“It was an obsession that claimed them all,” the curator whispered in revered tones. The “them” to which he referred were Scott, Shackleton, and Amundsen, their obsession the exploration of the polar regions during the heroic era of exploration in the early years of the twentieth century. Looking at the equipment they used, it seemed hardly surprising and made my attempt on the North Pole the following year in Gore-Tex and Kevlar seem somehow lightweight—both literally and metaphorically—compared to their sepia-hued, superhuman feats featured on the walls and in the display cabinets all around us.

“May I introduce Alexandra Shackleton, granddaughter of Sir Ernest?” said another voice beside me. This time it was that of my good friend Geraldine. I turned to greet Alexandra with the respect the Shackleton name instantly commands, particularly in the hallowed surrounds of the Greenwich Maritime Museum. It was 2002 and we were there for the opening of the exhibition South, a celebration of the achievements of Alexandra’s grandfather, Scott, and Amundsen, but perhaps also a recognition of the esteem with which Shackleton’s account of the Endurance expedition of 1914–17 of the same name was regarded.

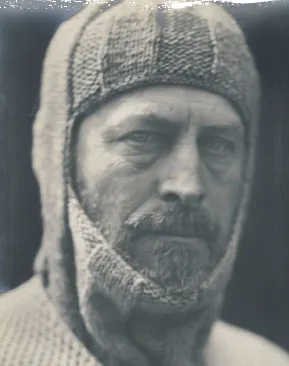

Mawson—scientist, explorer, survivor.

Courtesy of the National Library of Australia

Frank Hurley, National Library of Australia, vn4925816

Courtesy of the National Library of Australia

Frank Hurley, National Library of Australia, vn4925816

Me, re-creating Mawson’s desperate journey of survival.

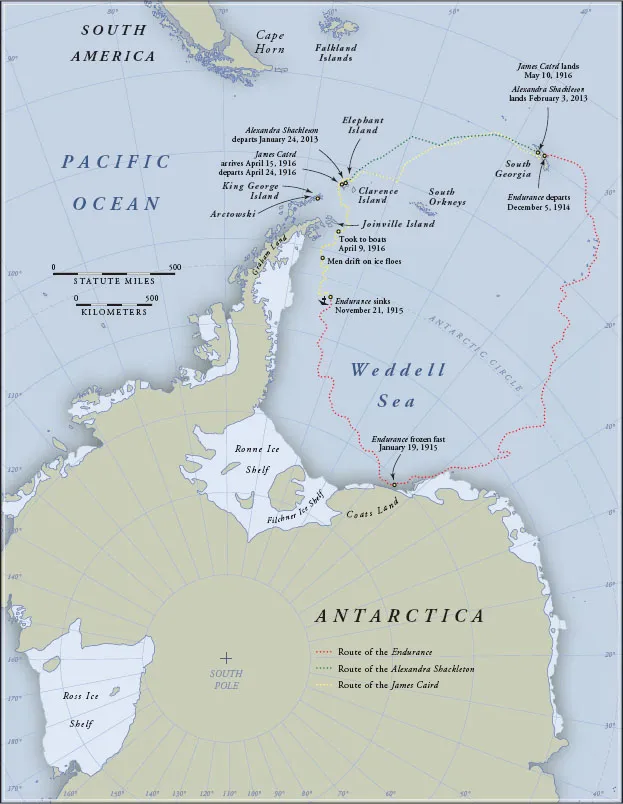

The route of the ill-fated Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1914–1916.

Courtesy of Ian Faulkner

Courtesy of Ian Faulkner

Mawson’s achievements were noticeably absent from the exhibition, but Zaz, as Alexandra prefers to be known, was intrigued by my plans to retrace his journey the old way with the same starvation rations and hundred-year-old equipment. “It sounds fascinating,” she commented. “And what might you do if you are successful with that journey?” The significance of this question would not become clear until years later.

On my completion of the Mawson expedition, Zaz was one of the first to call to congratulate me on my success and praise the way in which I’d done it. I had kept it as true to the original journey as possible, with the notable exceptions being that no one died and we ate neither dogs nor men. This was something of a relief for my backers but even more so for my expedition partner, John Stoukalo, who was slightly concerned at the prospect of having to die halfway through like the ill-fated Mertz. The trip had been incredibly challenging, with more weight loss than ever before, a return of the old frostbite injuries plus a few new ones, and the need to plumb new depths of physical and mental resolve in order to complete the journey. But I had seen no need for the calories that eating another would have provided.

“What next?” Zaz asked innocently enough but with both of us knowing exactly what she meant. Through our close friendship that had developed since our first meeting, I knew she rued the fact that no one had successfully re-created her grandfather’s famous “double” as he had done it—a journey across the Southern Ocean in a replica James Caird followed by a climb across the mountainous interior of South Georgia. When one looked at the difficulty levels and the inherent danger, it was hardly surprising. “I would like you to lead a team to attempt this,” she stated. They were powerful words and, although I had anticipated them, they still made my pulse quicken. “I would be proud to,” I replied. With those few words I knew a cast-iron commitment had been made, one that Shackleton would have expected me to honor and that neither of us would let go.

Shackleton’s original expedition followed Amundsen and Scott, reaching the South Pole in 1912. Not to be outdone, Shackleton decided to embark on the most ambitious polar expedition of them all—the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition (ITAE), a bid to cross Antarctica on foot from the Weddell Sea coast to the Ross Sea coast in what he described as “the one great main object of Antarctic journeyings.” In an interview for the Daily Mirror entitled “My Talk with Sir Ernest Shackleton,” William Pollock asked Shackleton why he was going on a South Polar expedition after Amundsen and Scott had succeeded in reaching the Pole itself. “He began to talk of the scientific, geographical and other benefits which he hoped would result from such an expedition,” wrote Pollock, “and then, suddenly fixing his eyes upon me, he said: ‘Besides, there’s a peculiar fascination about going. It’s hard to explain it in words—I don’t think I can quite explain it—but there’s an excitement, a thrill—a sort of magnetic attraction about polar exploration.’ ”

ITAE planned to use two ships to accomplish its goal. The first ship, the Endurance, on which Shackleton traveled, would land at a site near Vahsel Bay, adjacent to the Ronne Ice Shelf in the Weddell Sea. From here Shackleton would begin his attempt to cross the continent by a route that interestingly was very similar to the starting point of my bid to cross Antarctica in 1999–2000 that left from nearby Berkner Island on the Ronne Ice Shelf. The second ship, Mawson’s former vessel the Aurora, would leave from Hobart under the command of Aeneas Mackintosh and land at McMurdo Sound on the Ross Sea side. Its men would then lay a series of food caches in toward the Pole from their side that the crossing team would access once they passed the Pole.

Shackleton had learned from mistakes made on previous expeditions and was taking a large team of dogs, dietary precautions against scurvy, and a Royal Marine physical-fitness instructor, Thomas Orde-Lees, whose role among other things would be to teach the men to ski. Their improved diet, the result of painstaking research and analysis by Shackleton and Colonel Wilfred Beveridge of the Royal Army Medical Corps in a bid to minimize the risk of scurvy, undoubtedly helped their cause. It turned out, however, that neither the dogs nor an ability to ski would be needed, given the events that transpired.

The Endurance left Grytviken, South Georgia, in early December 1914 and headed south, bound for Vahsel Bay, in a year when the sea ice was the worst the whalers had ever experienced. For a week the ship, which was powered by engine and sail, barged and cajoled her way through the pack, her thick hull specifically designed for the purpose. But with Vahsel Bay still some 135 kilometers distant, the ice finally formed an impenetrable barrier many meters thick to the horizon in every direction. The same winds that supplemented the power from the Endurance’s engines by filling her sails and pushing her onward were, ironically, largely responsible for driving the vast mass of pack ice hard up against Antarctica, trapping them in the process.

After many attempts to free themselves, Shackleton announced on February 24 that the ship was officially a winter station and suspended ship routine, accepting that they were not going to escape the ice until the following spring or summer. He now had to get twenty-eight men from disparate backgrounds to live together harmoniously—not easy given that the sailors had been expecting to head back to civilization soon after dropping off the “shore party” of expeditioners and scientists. With big personalities involved and wide-ranging personal likes and dislikes bubbling below the surface, it was a huge challenge.

What the ice gets, the ice does not surrender: the Endurance beset by ice.

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, SLIDES 22/143

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, SLIDES 22/143

Shackleton established a structured routine of social activity, including lantern evenings, regular exercise, and tending to the dogs, and he relocated all of the men’s living quarters down into the warmest part of the ship. Now the eccentricities of his recruitment process came to the fore: the optimism and flexibility he had looked for in each man began to pay dividends. Shackleton held optimism almost above all else, calling it “true moral courage,” and they would need all they had to get through.

The Endurance remained beset until September, when the ice started to break up. The men greeted this positively and started speculating about their being freed and perhaps being able to continue south. But actually it signified great danger—the kind of danger one gets when rafts of ice many meters thick and the size of cities are driven together by powerful forces of wind and currents. The resulting “pressure” will crush anything in its path, even the strongest ice-strengthened vessel like the Endurance, especially when she was embedded in the ice. “Pressure” was a very apt description of the situation in which they now found themselves: on their own in this alien world with no one knowing they were there and with no means of communicating with anyone.

A man’s best friends: Shackleton’s ship and his dogs on ice.

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, SLIDES 22/13

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, SLIDES 22/13

By October the intense pressure of the ice had breached the stricken ship’s hull and she was sinking despite bilge pumps and men operating around the clock to try to save her. On October 27 Shackleton ordered the men to abandon ship, setting up camp in tents on the ice nearby. Immediately and...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword by Alexandra Shackleton

- Chapter 1: South

- Chapter 2: Endurance

- Chapter 3: Wooden Boats

- Chapter 4: Iron Men

- Chapter 5: Proceed

- Chapter 6: The Great Gray Shroud

- Chapter 7: Tempest

- Chapter 8: Threading the Needle

- Chapter 9: Impatience Camp

- Chapter 10: Third-Man Factor

- Chapter 11: Fall Line

- Chapter 12: Never the Lowered Banner

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- About the Publisher