- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The definitive history of MI9's emergency escape and evasion mapping programme and the contribution the maps made to victory in 1945. Fascinating stories of secret maps used by prisoners of World War II.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Great Escapes by Barbara Bond in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE CREATION OF MI9

‘Escaping and evading are ancient arts of war.’

(Field-Marshal Sir Gerald Templar, in the Foreword to MI9: Escape and Evasion, 1939–1945 by M. R. D. Foot and J. M. Langley)

MI9 was created on 23 December 1939 as a new branch of British intelligence to provide escape and evasion support to captured servicemen and to airmen shot down over enemy-held territory through the course of World War II. Arguably, it was not soon enough, as, less than six months after its creation, thousands of British Service personnel found themselves captured on the beaches at Dunkirk. MI9 was established within the Directorate of Military Intelligence, which came into existence in 1939 when, with the Directorate of Military Operations, it superseded a previously combined Directorate of Military Operations and Intelligence. Five of the Military Intelligence sections, MI1 to MI5, continued their work within the new Directorate, dealing, as before, with organization, geographic, topographic, coded communication and security matters.

The creation of MI9 stemmed from the experience of many during World War I, when military philosophy about prisoners of war underwent a sea-change. From regarding capture and captivity in enemy hands as a somewhat ignominious, even shameful and disgraceful fate, the value that escaping prisoners of war might contribute to the success of the war effort gradually came to be recognized. Men who escaped or evaded capture and returned to Britain brought back vital intelligence and boosted the morale of the Armed Services and, not least, their own families. In addition, the considerable effort required to prevent escapes from the camps deflected the enemy’s resources from front-line combat action.

In the late 1930s, as the prospect of war became increasingly likely, proposals for the creation of a section tasked to look after the interests of British prisoners of war came from many quarters, not least from Lieutenant Colonel (later Field-Marshal) Gerald Templar who had written to the Director of Military Intelligence in September 1939. A number of conferences with those who had been prisoners of war during World War I had also been arranged by MI1, seeking to benefit from their collective experiences. The actual proposal to the Joint Intelligence Committee to create such a branch came from Sir Campbell Stuart, who chaired a War Office Committee looking at the coordination of political intelligence and military operations. There had clearly been some robust discussions, since Viscount Halifax, appointed Foreign Secretary in February 1938 by the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, had indicated in a letter dated 5 December 1939 to Sir Campbell that his preference was for the section to be under Foreign Office control, with direct Treasury funding, presumably to ensure joint control and coordination with MI6, the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS). Notwithstanding this high-level opposition, the creation of MI9 went ahead in the War Office and it was made responsible to the Deputy Director for Military Intelligence, initially working closely with the Admiralty and the Air Ministry. With hindsight, the later animosity and conflict between MI9 and SIS (see Chapter 9) might well have had its roots in the initial difference of opinion as to where the newly formed section should sit in the governmental hierarchy.

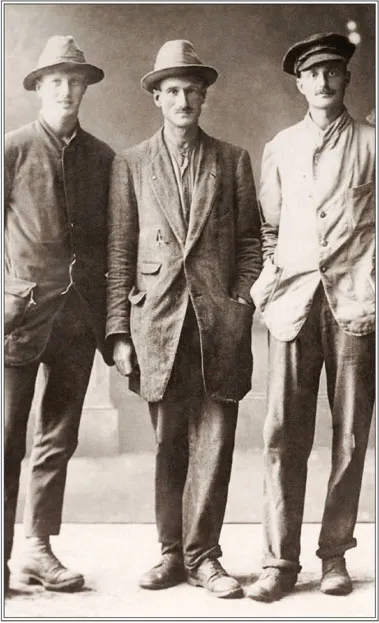

Three British prisoner of war escapers who tunnelled out of Holzminden prisoner of war camp in Germany during World War I on 23 July 1918. That night twenty-nine men made good their escape, ten of whom made their way to the neutral Netherlands some 320 kilometres (200 miles) from the camp and eventually back to Britain. Left to right: Captain Caspar Kennard, Major Gray and Lieutenant Blair, all of the Royal Flying Corps.

Sir Campbell Stuart (1885–1972), who made the initial proposal for the creation of MI9 to the Joint Intelligence Committee in 1939.

MI9’s objectives and methods were first outlined in the ‘Conduct of Work No. 48’, issued by the Directorate of Military Intelligence on 23 December 1939. In MI9’s War Diaries (the regular record of daily, weekly or monthly activities undertaken by the War Office branches during the war), its objectives were more fully described as:

i) To facilitate the escape of British prisoners of war, their repatriation to the United Kingdom (UK) and also to contain enemy manpower and resources in guarding the British prisoners of war and seeking to prevent their escape.

ii) To facilitate the return to the UK of those who evaded capture in enemy occupied territory.

iii) To collect and distribute information on escape and evasion, including research into, and the provision of, escape aids either prior to deployment or by covert despatch to prisoners of war.

iv) To instruct service personnel in escape and evasion techniques through preliminary training, the provision of lecturers and Bulletins and to train selected individuals in the use of coded communication through letters.

v) To maintain the morale of British prisoners of war by maintaining contact through correspondence and other means and to engage in the specific planning and execution of evasion and escape.

vi) To collect information from British prisoners of war through maintaining contact with them during captivity and after successful repatriation and disseminate the intelligence obtained to all three Services and appropriate Government Departments.

vii) To advise on counter-escape measures for German prisoners of war in Great Britain.

viii) To deny related information to the enemy.

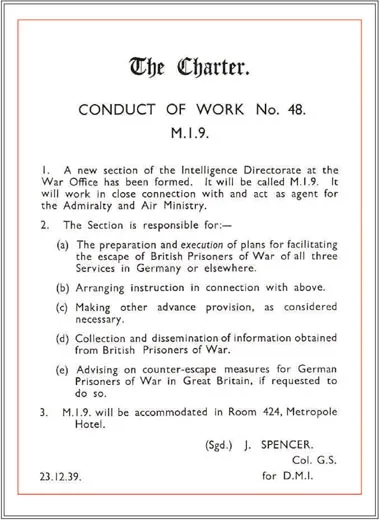

The original Conduct of Work No. 48 for MI9, produced by the Directorate of Military intelligence (DMI) and issued to MI5 and MI6, as it appears in Per Ardua Libertas, a photographic summary of MI9’s work, produced by Christopher Clayton Hutton in 1942.

The responsibilities included a mixture of operations, intelligence, transport and supply. The newly formed section was initially located in Room 424 of the Metropole Building (formerly the Metropole Hotel) in Northumberland Avenue, London, close to the War Office’s Main Building.

NORMAN CROCKATT

The newly appointed Head of MI9 was Major, later promoted to Colonel and eventually to Brigadier, Norman Richard Crockatt (1894–1956), a retired infantry officer who had seen active service in World War I in the Royal Scots Guards. Crockatt had left the Army in 1927, worked in the City and was in his mid-forties at the outbreak of World War II.

Whilst he had been decorated in World War I (DSO, MC), he had never been captured and, therefore, had no experience of being a prisoner of war. He proved, however, to be an admirable choice to ensure the fledgling section made good progress in its infancy and throughout the war, being ‘clear-headed, quick witted, a good organizer, a good judge of men, and no respecter of red tape’ (as recorded by M. R. D. Foot and J. M Langley in their definitive history MI9: Escape and Evasion, 1939–1945, hereafter referred to as Foot and Langley). These qualities were to stand him in good stead for the work he tackled in the next six years. He also recognized the importance of keeping his section small, concentrated in its activities and low profile among other intelligence sections, attributes which appeared to ensure that when the time came to expand its activities, it received little opposition from those competing for military priorities and budgets. Crockatt realized the value of having the experience of former prisoners of war, especially those who had successfully escaped, and appointed many with that experience to the small cadre of lecturing staff based in the Training School established by MI9.

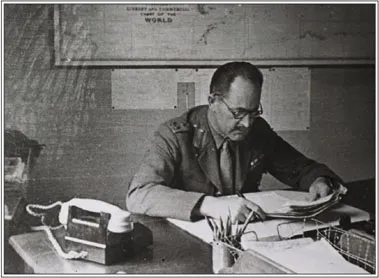

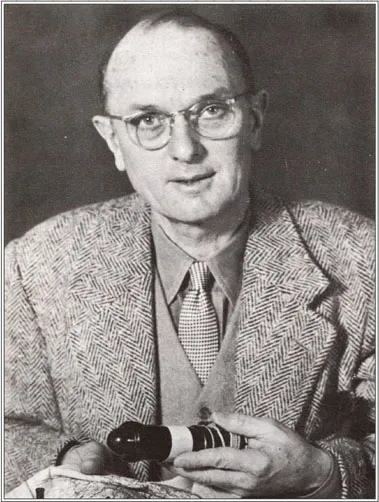

Brigadier Norman Crockatt in the MI9 headquarters at Wilton Park near Beaconsfield in 1944.

The initial budget given to Crockatt to set up the entire section was £2,000. In present day terms, this equates to a sum of approximately £90,000. He embarked on a recruitment campaign and, by the end of July 1940, the complement of officers in the whole of the MI9 organization had risen to fifty. By that time, Crockatt was looking to move his organization out of London and by September 1940, he had selected Wilton Park, near Beaconsfield, as an appropriate location. After necessary refurbishment and the installation of telephones, most of the MI9 staff moved there on 14–18 October and occupied No. 20 Camp at Wilton Park.

ORGANIZATION

The section was initially organized into two parts: MI9a was responsible for matters relating to enemy prisoners of war and MI9b was responsible for British prisoners of war. The former subsequently became a separate department, MI19, to facilitate the handling and distribution of the intelligence information emanating from the two groups. On separation, the remaining MI9b was re-organized into separate sections and the staff complement was significantly increased:

Section D was responsible for training, including the Training School which was established at the Highgate School in north London, from which the staff and pupils had been evacuated. It was subsequently designated the Intelligence School (IS9) in January 1942.

Section W was responsible for the interrogation of returning escapers and evaders, including the initial preparation of the questionnaires which the interviewees were required to complete. The principal aim of the questionnaires was to identify information for use in the lectures and the Bulletin. The section was also responsible for the preparation and distribution of reports and for writing the daily, later to become monthly, War Diary entry.

Section X was responsible for the planning and organization of escapes, including the selection, research, coordination and despatch of escape and evasion materials. Because of the small numbers of staff, the section was unable to spend much time on this activity until January 1942 when its establishment was boosted. At that point, they were also able to increase the volume of information to Section Y for transmission to the camps.

Section Y was responsible for codes and secret communication with the camps. The development of letter codes as a means of communication with the camps was regarded as a priority from the start and the role which coded communication played in the escape programme is discussed in detail in Chapter 5.

Section Z was responsible for the production and supply of escape tools, including all related experimental work.

It is primarily these last three sections whose activities largely, but not exclusively, form the focus of this book.

KEY STAFF

Christopher Clayton Hutton

Christopher William Clayton Hutton (1893–1965), known as ‘Clutty’ by all who worked with him, was appointed on 22 February 1940 as the Technical Officer to lead Section Z. He was the boffin, the inventor of gadgetry. His fascination for show business, particularly magicians, was apparently regarded as sufficient qualification for the post he was given as the escape aids expert in MI9. It was his innate interest in escapology and illusion which was to prove the source of his imagination and ingenuity. Whilst working in his uncle’s timber business in Park Saw Mills, Birmingham prior to World War I, he had challenged Harry Houdini to escape from a packing case constructed on the stage of the Birmingham Empire Theatre. Houdini escaped, for, unbeknown to Hutton, he had bribed the carpenter. In the inter-war years, he worked as a journalist and later in publicity for the film industry.

Christopher Clayton Hutton, who led MI9’s Section Z from 1940 to 1943, where he developed many ingenious escape aids and initiated the escape and evasion mapping programme.

Hutton had served in the Yeomanry, the Yorkshire Regiment and as a pilot in the Royal Flying Corps during World War I. Realizing that another war with Germany was imminent, he tried to volunteer for the Royal Air Force and, subsequently, for the Army. When these approaches did not receive the encouragement he sought, he wrote a number of times to the War Office seeking an opening in an Intelligence Branch, an approach which eventu...

Table of contents

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Creation of MI9

- Chapter 2: Background to the Mapping Programme

- Chapter 3: The Map Production Programme

- Chapter 4: Smuggling Maps and Other Escape Aids into the Camps

- Chapter 5: Coded Correspondence with the Camps

- Chapter 6: The Schaffhausen Salient and Airey Neave’s Escape

- Chapter 7: Escaping Through the Baltic Ports

- Chapter 8: Copying Maps in the Camps

- Chapter 9: MI9 and its Contribution to Military Mapping

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Illustration and Photographic Credits

- Index

- About the Publisher