eBook - ePub

From Empire to Europe

The Decline and Revival of British Industry Since the Second World War

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

From Empire to Europe

The Decline and Revival of British Industry Since the Second World War

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access From Empire to Europe by Geoffrey Owen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

Falling Behind and Catching Up

In the summer of 1995, a ceremony was held at the Aylesford paper mill in Kent, one of Britain’s largest paper-making sites, to mark the successful commissioning of a newsprint machine. In forest-rich countries such as Canada or Finland, this would have been an unremarkable event. But for Britain the Aylesford project had a special significance. It was the first new machine to be built at the mill for more than thirty years. Based on recycled paper, it produced newsprint which was competitive in cost and quality with imports. The project was financed by two non-British companies, one from Sweden and the other from South Africa. By investing £250m at Aylesford, they were contributing to the revival of an industry which twenty years earlier had seemed in the grip of irreversible decline.

What happened in paper-making during the 1980s and 1990s illustrates the central theme of this book – the delayed modernisation of British industry. For the first decade after the war British paper-makers led a comfortable existence. Domestic demand was strong, and import competition was restrained by tariffs and quotas. These easy conditions came to an abrupt end in 1959 when the Conservative government under Harold Macmillan decided to participate in the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). This was a grouping of countries outside the six-nation Common Market, and it included Sweden and Finland, both of which had large, efficient paper industries based on cheap electricity and ample supplies of wood.1

As tariffs among the EFTA countries came down, the Nordic paper producers used their cost advantage to increase their exports to Britain. British firms strove to come to terms with a difficult trading environment. Mills and machines were closed down, and some of the leading British companies lost faith in the industry’s future. But the economics of paper-making in Britain were not as unfavourable as the pessimists supposed. For some grades of paper, being near to the market turned out to be more important than being near to the forests. In addition, Britain had a man-made ‘forest’ of its own: improvements in recycling technology created new opportunities for using waste paper instead of imported woodpulp as the feedstock for paper production. The gloom began to lift in the early 1980s, and over the next fifteen years a remarkable transformation of the industry took place, involving new investment and changes of ownership. Some of the new projects, like the Aylesford newsprint machine, were undertaken by foreign companies. But there was also a new spirit of confidence among the surviving British-owned firms, targeting sectors of the market where a UK-based producer could compete successfully against imports.

A similar chain of events took place in other industries: profitable growth in the first few years after the war, a struggle to cope with increasing international competition in the 1960s and 1970s, and, finally, integration into the world market. The form which integration took varied according to the circumstances of each industry and the amount of ground that had been lost in earlier years. The revival of the British motor industry, for example, which had almost been given up for dead at the end of the 1970s, owed a great deal to the decision by three Japanese companies – Toyota, Honda and Nissan – to choose Britain as the site of their first European assembly plants. By the end of the 1990s, after Jaguar had been bought by Ford, Rover by BMW and Rolls-Royce Motors by Volkswagen, virtually the whole of the British motor industry had passed into foreign control. While this was a blow to national pride, the willingness of these companies to invest on a large scale in British car factories was an indication of how much had changed since the dark days of the 1970s.

With or without the involvement of foreign companies, the 1980s saw a vigorous effort throughout British industry to correct past mistakes and to build defensible positions in the world market. Guest Keen and Nettlefolds (GKN) was an old-established company which had diversified in the inter-war years from its original base in steel-making into a wide range of steel-using businesses, and it continued to do so in the 1950s and 1960s. Most of its sales were to customers in Britain and the Commonwealth. In the second half of the 1970s, when competition increased and profits came under pressure, a new approach was necessary. As Trevor Holdsworth, chairman of the company from 1979 to 1986, put it later: ‘We were drifting uncertainly into the future without a clear strategy. A new generation of senior executives was emerging and we set about trying to make sense of our inheritance. We had to find new products, new technology and we had to spread internationally.’2 The chosen path for expansion was in vehicle components, and over the next decade GKN converted itself into a leading supplier to the world motor industry, with a strong market position in Continental Europe and the US. Other companies went through similar upheavals. The common elements were specialisation and internationalisation, and a drive to raise manufacturing efficiency closer to the best world standards.

What precipitated these changes? Why did they occur in the 1980s, and not thirty years earlier?

During the 1970s a series of shocks – Britain’s entry into the Common Market, the rise of Japan and the newly industrialising countries, the slowdown in the world economy after the first oil crisis – exposed weaknesses in British industry which had been partially obscured and more easily tolerated in the earlier post-war years. By the end of the decade companies such as GKN were forced to take a more critical look at themselves, and decide which of their businesses, if any, could compete on the world stage.

These external pressures coincided with a change in the political climate within Britain. The election of a Conservative government under Margaret Thatcher in May 1979 heralded a break with the past in the management of the economy. A fierce determination to defeat inflation through strict monetary and fiscal policies was combined with a greater emphasis on competition and deregulation. Virtually all the industries which had been nationalised since 1945 – and some, like the telephone network, which had been in government hands for much longer – were transferred to the private sector. The labour relations system, which had been partly responsible for Britain’s reputation as the sick man of Europe, was drastically reformed.

A third ingredient was the phenomenon which came to be known as globalisation. During the 1980s increasing cross-border investment altered the structure of several major industries, paper and cars being two notable examples. Many of the world’s leading companies built or acquired factories in their major markets, and organised their manufacturing and distribution on an international basis. Britain benefited from this process because, thanks to Margaret Thatcher, it had become a more attractive location for investment. The Conservative government was also more relaxed than its predecessors about allowing former ‘national champions’ to be acquired by foreign companies; no objection was raised when BMW bought Rover, or when ICL, the computer manufacturer, was sold to Fujitsu of Japan.

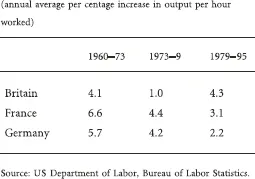

The combined effect of international competition, domestic policy reform and foreign investment brought to an end a long period in which productivity in British manufacturing had grown more slowly than in other European countries (TABLE 1.1). After years of falling behind, Britain was catching up.

This book describes how the transition came about. It focuses on firms and the people who ran them, and on the domestic and international environment in which they were operating. The aim is to identify the reasons for Britain’s poor industrial performance, compared to other European countries, in the first thirty years after the war, and to assess the significance of the changes that occurred in the 1980s and 1990s.

TABLE 1.1 Labour productivity in manufacturing 1960–95

What firms can do in international competition is constrained by the economics of the industry they are competing in and by the conditions which they face in their home base: countries provide a better ‘global platform’ for some industries than for others.3 In some cases companies may derive a competitive advantage from the size and character of domestic demand for their products. In others the crucial factor may be ease of access to essential raw materials. But the most important influence on the international competitiveness of companies, especially in manufacturing, is the extent to which they are helped or hindered by national institutions and policies. To take one example, the US has developed since the Second World War a large and sophisticated community of venture capitalists, who have supported the growth of start-up firms in high-technology industries such as electronics and biotechnology. While access to venture capital is not the only reason for the success of American companies in these industries, it is an institutional asset which other countries do not possess.

Institutions and policies have been central to the long-running controversy about British industrial decline. Three culprits which have figured prominently in the debate – the financial system, the training and education system and the labour relations system – are given special attention in this book. The financial system is accused of failing to provide manufacturing companies with the constructive, long-term support which is available in other countries. The education system has been criticised for being too detached from the world of industry, leading to an inadequate supply of technical and managerial skills. The labour relations system is held responsible for the collapse of strike-prone industries such as shipbuilding and cars, and more generally for the slow growth of productivity in British industry as a whole between the 1950s and the 1970s. These institutional weaknesses have been aggravated, some commentators believe, by policy errors on the part of post-war governments. The management of the economy has been erratic, while micro-economic or ‘supply-side’ policies, ranging from nationalisation to the promotion of mergers, have often been ill-considered and counter-productive.

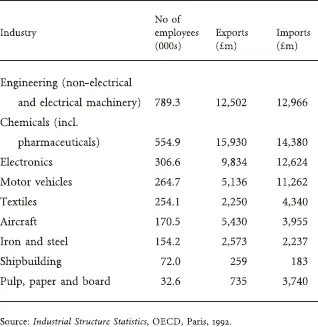

Opinions differ about the relative importance of these factors, and about the extent to which some of the alleged weaknesses – for example, the ‘short-termism’ of British financial markets – continue to put British firms at a disadvantage today. This book seeks to shed light on these issues by making comparisons across countries and across industries. It examines how British firms in a number of major industries responded to international competition after the Second World War, and compares their response with that of their counterparts in other European countries, principally Germany and France; the list of industries covered is set out in TABLE 1.2.

Some British industries did better than others, and the same was true in the two Continental countries. At the end of the 1990s British-owned firms ranked among the world leaders in chemicals and pharmaceuticals, but not in cars. German companies were outstandingly successful in mechanical engineering, but not in computers or television sets. French manufacturers out-performed their British counterparts in cars, but not in machine tools. The purpose of the industry case studies contained in later chapters is to explore the reasons for these national strengths and weaknesses, and thus to illuminate the larger question of how institutions and policies have affected industrial performance.

In studying the interaction between firms, industries and nations, history matters at all three levels. Although the book is primarily concerned with events after 1945, each of the case studies begins by examining the earlier history of the firms and industries concerned. Did British industry enter the post-war period with managerial and technical weaknesses inherited from the past, or was its poor performance after 1945 due to the things that were done or not done in the post-war period itself?

This is a book about British manufacturing, not about the British economy. The focus on manufacturing is not meant to imply that making things is a more important activity than providing services. The proportion of the workforce employed in manufacturing has been declining for many years in Britain, as it has in other industrial countries, and the trend is certain to continue. A nation’s economic strength cannot be considered in terms of manufacturing alone, and some might argue that, by excluding non-manufacturing sectors such as the media and financial services, this book is underplaying the things which British firms are good at. Nevertheless, the post-war history of British manufacturing is a large and complex subject in its own right, and the focus on this part of the economy seems justified in view of the many unresolved controversies which surround it.

TABLE 1.2 The case study industries in 1988

PART I

Historical Background

TWO

The Consequences of Coming First

There is a widely held view that British industrial decline began in the closing decades of the nineteenth century and has continued remorselessly ever since. According to this account, British entrepreneurs, having led the world in the first industrial revolution, failed to adapt to competition from the two late-industrialising countries, Germany and the US. British industry was locked into a set of institutions and management practices which had become obsolete. The financial system was not well organised to supply risk capital for the new industries of the second industrial revolution; the education system did not produce enough scientists and engineers; and the labour relations system slowed down the introduction of new manufacturing methods.

It is certainly true that Britain was caught up by the US and Germany between 1870 and 1914. It is also true that the institutions and capabilities which the two late-comers developed were different from those on which the British industrial revolution had been based. One well-known example is the emergence in Germany of the big universal banks, led by Deutsche Bank, which made long-term loans to their industrial clients and organised stock market flotations for them, while British banks concentrated almost entirely on short-term lending. Another is the creation in the US towards the end of the nineteenth century of large, professionally managed corporations, while British businessmen still clung to what Alfred Chandler, the American business historian, has called personal capitalism – a structure of small, family-controlled firms, lacking the economies of scale enjoyed by their US counterparts.1

A much-debated issue is whether Britain’s inability to match these and other innovations constitutes an entrepreneurial failure, and, if so, whether the failure was sufficiently serious and long-lasting to be relevant to what happened after 1945. Was it a disadvantage to have come first?

The Growth of British Industry from 1750 to 1870

Britain’s industrial revolution, which began in the second half of the eighteenth century, was driven by technological change in three sectors. The pace-setter was cotton textiles. The substitution of machines for human effort in the spinning and weaving of cotton generated a huge domestic and international demand for a fabric which had previously been too expensive to capture a mass market. Second, new iron-making techniques – the replacement of charcoal by coke in the smelting of iron ore and the ‘puddling’ process for refining pig iron – increased the supply and lowered the price of wrought iron, which became the building block of the industrial revo...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- 1. Falling Behind and Catching up

- Part I: Historical Background

- Part II: Industries and Firms

- Part III: Institutions and Policies

- Afterword

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- About the Publisher