- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

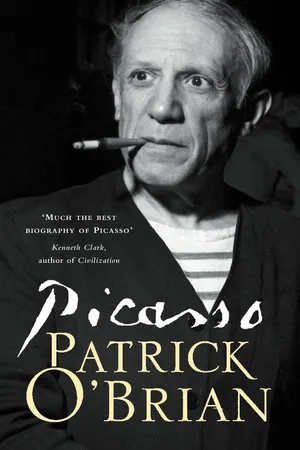

A scholarly, passionate and brilliantly-written biography of Pablo Picasso by Patrick O’Brian, the famous author of the much-loved Aubrey-Maturin series, reissued in a stunning new cover.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

HarperCollinsYear

2012Print ISBN

9780007173570eBook ISBN

97800074663821

PICASSO was born on October 25, 1881, in Málaga, the first, the only son of Doña María Picasso y Lopez and her husband, Don José Ruiz y Blasco, a painter, a teacher in the city’s art school, and the curator of the local museum. The statement is true: it is to be found in all the reference-books. But perhaps it does not convey a great deal of information except to those Spaniards who can as easily visualize the Málaga of Alphonso XII’s time as English-speaking readers can the St. Louis of President Arthur’s or the Southampton of Queen Victoria’s—to those who know the economic, cultural, and social position of a middle-class family in that town and the pattern of life in nineteenth-century Andalucía as a whole. For even the strongest individual is indelibly marked by the culture in which he is brought up; even the loneliest man is not an island; and even Picasso carried his cradle with him to the grave. “A man belongs to his own country forever,” he said.

Picasso’s Málaga, then, was an ancient city in the far south of Spain, an essentially Mediterranean city, and after Barcelona the country’s most important seaport on that coast: it had been a great port for centuries before Barcelona was heard of, having a natural harbor as opposed to Barcelona’s open beach; but long before Picasso’s time the silting up of this harbor and the activity of the Catalans in building moles had reversed the position, and whereas in 1881 ships had to lie off Málaga and discharge their cargoes into lighters, in Barcelona they could tie up in their hundreds alongside the busy quays. Yet Málaga still had a great deal of shipping; its great bay provided shelter, and the smaller vessels could still use the harbor at the bottom of that bay, where the white town lies along the shore with the hills of Axarquía rising behind it, while the Gibralfaro rears up five hundred feet and more in the city itself, with a huge Moorish castle standing upon its top.

Compared with the booming town of the present day, the Málaga of 1881 belonged to a different world, a world innocent of concrete and in many ways much nearer to the middle ages than to the twentieth century: tourism has changed it almost beyond recognition. When Picasso was born Málaga still relied upon its ancient industries, shipping, cotton-spinning, sugar-refining, the working of iron, and the production of wine, almonds and raisins, and other fruit: the fertile, irrigated, subtropical plain to the west of the town supplied the cotton and the sugar-cane (the Arabs brought them to Spain) as well as oranges, lemons, custard-apples, and bananas, while the slopes behind produced almonds, the grapes for the heavy, potent wine and for the raisins; and iron-ore came from the mountains. The city of that time had only about 120,000 inhabitants as opposed to the present 375,000 (a number enormously increased by holiday-makers from all over Europe in the summer), and they lived in a much smaller space: there was little development north of the hills or beyond the river, and what is now land on the seaward side was then part of the shallow harbor. This made for a crowded, somewhat squalid city, particularly as there was little notion of drains and the water-supply was inadequate; a real city, however, with its twenty-seven churches and chapels, its four important monasteries (the survivors of a great many more before the massive suppressions, expropriations, and expulsions of 1835), its bullring for ten thousand, its still-unfinished cathedral on the site of a former mosque, its splendid market in what was once the Moorish arsenal, its garrison, its brothels, its theaters, its immensely ancient tradition, and its strong sense of corporate being. Then, as now, it had the finest climate in Europe, with only forty clouded days in the year; but in 1881 traveling in Spain was an uncommon adventure and virtually no tourists came to enjoy the astonishing light, the brilliant air, and the tepid sea. Only a few wealthy invalids, consumptives for the most part, took lodgings at the Caleta or the Limonar, far from the medieval filth and smells of the inner town. They hardly made the least impression upon Málaga itself, which, apart from a scattering of foreign merchants, was left to the Malagueños.

Their town had been an important Phoenician stronghold until the Punic wars; then a Roman municipium; then a Visigothic city, the seat of a bishop; and then, for seven hundred and seventy-seven years, a great Arab town, one in which large numbers of Jews and Christians lived under Moslem rule. The Moslems were delighted with their conquest: they allotted it to the Khund al Jordan, the tribes from the east of the sacred river, who looked upon it as an earthly paradise. Many Arabic travelers spoke of its splendor, Ibn Batuta going so far as to compare it with an opened bottle of musk. Málaga was a Moslem city far longer than it has subsequently been Christian, and the Arabs left their mark: even now one is continually aware of their presence, not only because of the remains of the Alcazaba, a fortified Moorish palace high over the port, and of the still higher Gibralfaro, from which the mountains in Africa can be distinguished on the clear horizon, but also because of the faces in the streets and markets and above all because of the flamenco that is to be heard, sometimes from an open window, sometimes from a solitary peasant following an ass so loaded with sugar-cane that only its hoofs show twinkling below.

The Spaniards who reconquered Andalucía came from many different regions, each with its own way of speaking; and partly because of this and partly because of the large numbers of Arabic-speaking people, Christian, Jew, and Moslem, they evolved a fresh dialect of their own, a Spanish in which the s is often lost and the h often sounded, a brogue as distinct as that of Munster: one that perplexes the foreigner and that makes the Castilian laugh. In time the Moors and the Jews were more or less efficiently expelled or forcibly converted, and eventually many of the descendants of these converts, the “new Christians,” were also driven from the country; but they left their genes behind, and many of their ways—their attitude towards women, for example. Then again there is a fierce democratic independence combined with an ability to live under a despotic regime that is reminiscent of the egalitarianism of Islam: no one could call the Spaniards as a whole a deferential nation, but this characteristic grows even more marked as one travels south, to reach its height in Andalucía. And as one travels south, so the physical evidence of these genes becomes more apparent; the Arab, the Berber, and the Jew peep out, to say nothing of the Phoenician; and the Castilian or the Catalan is apt to lump the Andalou in with the Gypsies, a great many of whom live in those parts. For the solid bourgeois of Madrid or Barcelona the Andalou is something of an outsider; he is held in low esteem, as being wanting in gravity, assiduity, and respect for the establishment. Málaga itself had a solid reputation for being against the government, for being impatient of authority: it was a contentious city, in spite of its conforming bourgeoisie. In the very square in which Picasso was born there is a monument to a general and forty-nine of his companions, including a Mr. Robert Boyd, who rose in favor of the Constitution and who were all shot in Málaga in 1831 and buried in the square; it also commemorates the hero of another rising, Riego, after whom the square was officially named, although it has now reverted to its traditional name of the Plaza de la Merced, from the church of Nuestra Señora de la Merced, which used to stand in its north-east corner. There were many other risings, insurrections, and pronunciamientos in Málaga during the nineteenth century, including one against Espartero in 1843, another against Queen Isabella II in 1868 (this, of course, was part of the greater turmoil of the Revolution), and another in favor of a republic only eight years before Picasso’s birth. But although many of these risings, both in Málaga and the rest of Spain, had a strongly anticlerical element, with churches and monasteries going up in flames and monks, nuns, friars, and even hermits being expelled and dispossessed, the Spaniards remained profoundly Catholic, and the Malagueños continued to live their traditional religious life, celebrating the major feasts of the Church with splendid bull-fights, making pilgrimages to local shrines, forming great processions in Holy Week, hating what few heretics they ever saw (until 1830 Protestants had to be buried on the foreshore, where heavy seas sometimes disinterred them), and of course baptizing their children. It would have been unthinkable for Picasso not to have been christened, and sixteen days after his birth he was taken to the parish church of Santiago el Mayor (whose tower was once a minaret), where the priest of La Merced gave him the names Pablo, Diego, José, Francisco de Paula, Juan Nepomuceno, María de los Remedios, and Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad, together with some salt to expel the devil.

In most countries this array of names would imply an exalted origin: but not in Andalucía. The Ruiz family belonged to that traditionally almost non-existent body, the Spanish middle class. José Ruiz y Blasco, Picasso’s father, was the son of Diego Ruiz y de Almoguera, a glover and by all accounts an amiable and gifted man with artistic tastes, a great talker; but in that subtropical climate there was no fortune in gloves, and Don Diego also played the double-bass in the orchestra of the municipal theater. This Diego Ruiz was born in Córdoba in 1799, well before Goya painted the “Tres de Mayo,” and he remembered the French occupation of Málaga very well indeed (his father, José Ruiz y de Fuentes had removed there during the Peninsular War), for not only did the French sack the city in 1810, but they also beat the young Diego for throwing stones at them. It is said that they beat him almost to death, for it was during a general’s parade that he threw his stones: however that may be, he recovered sufficiently to set up shop in due time, to marry María de la Paz Blasco y Echevarria, and to have eleven children by her. It is the Spanish custom to use two surnames on formal occasions, one’s father’s and one’s mother’s, often connected with a y, but to hand down only the paternal half: thus Diego’s son José was called Ruiz y Blasco, both the Almoguera and the Echevarria disappearing. Echevarria, by the way, is a name that has a Basque sound about it, and this may account for the often-repeated statement that Picasso’s father was of Basque origin. Then again a Spanish woman retains her patronymic on marrying and adds to it her husband’s, preceded by de, so that Diego’s wife was known as Señora Blasco de Ruiz.

As for origins, it has been attempted to be shown that the Ruiz family descended from one Juan de León, a hidalgo of immemorial nobility who had estates at Cogolludo in the kingdom of León and who was killed in 1487 during the war for the reconquest of Granada: his grandson settled at Villafranca de Córdoba; and he is said to be the ancestor of the Ruizes. It may be so; but the sudden and irregular appearance of the name Ruiz is not particularly convincing, even taking into account the strange anarchy of Spanish family names at that period. In any event this remote Leonese origin is scarcely relevant: for although, as Gibbon says, “we wish to discover our ancestors, but we wish to discover them possessed of ample fortunes, and holding an eminent rank in the class of hereditary nobles,” and although we sometimes succeed, the practical effect of the more or less mythical Don Juan on the Ruizes cannot have been very great four centuries and eleven generations later; nor can that of the Venerable Juan de Almoguera, Archbishop of Lima, Viceroy and Captain-General of Peru in the seventeenth century, who is stated to have been a collateral.

In more recent and verifiable times, however, there was another Juan de Almoguera, a Córdoban and a notary, who died in deeply embarrassed circumstances at Almodóvar del Río, leaving a widow and eleven children, the eldest of whom, María Josefa, married José Ruiz y de Fuentes, Picasso’s great-grandfather, while the tenth, Pedro Dionisio, became a hermit. He joined the Venerable Congregación de Ermitaños de Nuestra Señora de Belén in the mountains of Córdoba in 1792 and became their superior some twenty years later; his health was always poor and he could not always remain in his hermitage; nevertheless he nursed the sick most devotedly during the cholera epidemic of 1834. And when his community was suppressed, expropriated, and expelled at the time of the anticlerical outburst of 1835 he managed to retain a little of their land, a spot from which he could look out over the mountains. He died in 1856, at the age of eighty-one, and he left a vividly living memory: his great-grand-nephew Pablo often spoke of “Tío Perico, who led an exemplary life as a hermit in the Sierra de Córdoba.”*

The most diligent research has discovered little reliable information about Picasso’s maternal ancestors: they seem to have been obscure burgesses of Málaga for some generations; but Picasso’s maternal grandmother at least was tolerably well provided for, since she owned vineyards outside the town that supported her and her daughters until the phylloxera destroyed them. Her husband, Francisco Picasso y Guardeño, went to school in England, returned to his native Málaga, married Inés Lopez y Robles, had four daughters by her, and went off to Cuba: there he became a customs-officer and eventually died of the yellow fever, in 1883, the news taking some fifteen years to reach his family. The origin of the name Picasso, which is most unusual in Spain (the double s does not occur in Castilian), has resisted all inquiries: some writers have pointed to Italy and particularly to the Genoese painter Mateo Picasso, a nineteenth-century portraitist, and Pablo Picasso himself went so far as to buy one of his pictures. On the other hand, Jaime Sabartés, one of Picasso’s oldest friends, his biographer, secretary, and factotum, discovered a Moorish prince called Picaço, who came to Spain with eight thousand horsemen and who was defeated and slain in battle by the Grand Master of Alcántara on Tuesday, October 28, 1339. And there have been assertions of a Jewish, Balearic, or Catalan origin. These are not of the least consequence, however; the real significance of this unusual, striking name is that it had at least some influence in setting its owner slightly apart, of making him feel that he was not quite the same as other people—a feeling that was to be reinforced by several other factors quite apart from that isolating genius which soon made it almost impossible for him to find any equals.

To return to Diego Ruiz, the glover, Picasso’s paternal grandfather: in spite of his beating at the hands of the French soldiers, in spite of the near anarchy that prevailed in Spain almost without a pause from 1800 to 1874 (to speak only of the nineteenth century), in spite of the risings for or against the various constitutions, of the Carlist wars, the pronunciamientos, the continual (and often bloody) struggles between the conservatives, the moderados, and the liberals, in spite of the mutinous political generals, the loss of the South American possessions, the stagnation of trade, and the tottering national finances, Diego Ruiz, like so many of his relatives in Málaga, had an enormous family, four boys and seven girls.

The second of these boys, Pablo, had a vocation that must have rejoiced all his relatives: he entered the Church and did remarkably well, becoming a doctor of theology and eventually, although he had no gift for preaching, a canon of Málaga cathedral and his family’s main prop and stay.

The profession chosen by Salvador, the youngest boy, cannot have caused anything like the same satisfaction: he decided to study medicine at Granada, and at that time neither medicine nor medical men were much esteemed in Spain. Richard Ford, writing only a few years before Don Salvador began his studies, speaks of the “base bloody and brutal Sangrados,” observing that in all Sevilla only one doctor was admitted into good company, “and every stranger was informed apologetically that the MD was de casa conocida, or born of good family.” In Granada Don Salvador met a young woman, Concepción Marin, the daughter of a sculptor; and being unwilling to part from her he took a post at the hospital when he was qualified, at a salary of 750 pesetas a year. But although Spain was then a relatively cheap country he found that this sum, which at that time represented about $112, or £28, did not allow him to put by enough to marry and set up house; he returned to Málaga, practiced (the Reverend Dr. Pablo was useful to him and his patients included the French Assumptionist nuns and their schoolgirls as well as the convent of Franciscans, whom he did not charge), prospered, and in 1876, seven years after he had qualified, he married Concepción, who gave him two daughters, Picasso’s cousins Concha and María. Later Don Salvador became the medical officer of the port and he also founded the Málaga Vaccination Institute. He was a kind man and a brave one (in the anticlerical troubles he protected the nuns at the risk of his life), and from the financial point of view he did better than any Ruiz in Andalucía: it was as a successful, cigar-smoking physician that he attended Picasso’s birth, reanimating his limp and apparently stillborn nephew with a blast of smoke into his infant lungs. Later he also contributed to the support of young Pablo in Madrid and to the buying of his exemption when the time came for his military service.

But if Don Salvador’s choice of a calling met with certain reserves at first, his brother José’s can have caused nothing but dismay. Having some skill in drawing, a knack for illustration, he determined to become an artist, a painter; and for some years he persisted in this course. He acquired a fair academic technique; he had a craftsman’s talent and an ability to use his tools; but he had nothing whatsoever to say in terms of paint, or at least he never said it. He produced a large number of painstaking decorative pictures of dead game, flowers (particularly lilacs), and above all of live pigeons, a few of which he sold; and he painted fans. He lived with his elder brother, the Canon, who also supported his surviving unmarried sisters, Josefa and Matilde.

It is the sad fate of towns that have once been capital cities (and at one time Málaga was the seat of an independent Moorish king) that when they lose this status they become more provincial than those which never emerged from obscurity. Málaga was deeply provincial. Yet it did possess a struggling art-school, the Escuela de Artes y Oficios de San Telmo, which had been founded in 1849; and in 1868 the quite well known Valencian artist Bernardo Ferrándiz became its professor of painting and composition. He was followed by Antonio Muñoz Degrain, another Valencian (they had come to Málaga to decorate the Teatro Cervantes); and the presence of these two painters of more than local fame, more than common talent, coincided with a revival of interest in the arts—a small and temporary revival, perhaps, but enough to induce the municipality to set up a museum of fine arts on the second floor of the expropriated Augustinian monastery which they used as the town hall. José Ruiz succeeded his friend Muñoz Degrain at San Telmo and he was also appointed the first curator of the museum. His duties included the restoring of the damaged pictures, a task for which his meticulous craftsmanship and attention to detail suited him admirably: what is more, he had a room set aside for this work, and as the museum followed the ancient Spanish provincial tradition of being almost always shut, he did his own painting there as well.

It was a fairly agreeable life; he had a small but apparently assured income, and any paintings that he sold added jam to his bread and butter; he had many friends of a mildly bohemian character, some of them painters; and he delighted in the bull-fights, better conducted, better understood in Andalucía than anywhere else in the world: at all events it was the happiest life he ever knew.

But his youth was passing—indeed, it had passed: he was nearly forty—and his family urged him to marry. None of his brothers or sisters had yet produced a son, and the family name was in danger of extinction. They arranged a suitable marriage for him, and although he could not be brought to like the young woman of their choice he did make an offer to her cousin María—María Picasso y Lopez. Yet before the marriage could take place the Canon died: this was in 1878, and he was only forty-seven. His loss was felt most severely; and either because of this or because Don José felt little real enthusiasm for marriage, the wedding was not celebrated until 1880.

José Ruiz took a flat in the Plaza de la Merced, on the third floor of a double terrace recently built by a wealthy man, Don Antonio Campos Garvin, Marqués de Ignato, on the site of a former convent. Don José was now responsible for a wife, two unmarried sisters, a mother-in-law and, after 1881, a son. Then, in 1884, during a violent earthquake, a daughter appeared: three years later another: at some point María de Ruiz’s unmarried sisters Eladia and Heliodora, whose vineyards had been ravaged by the phylloxera, moved in. And in the meantime the municipality decided to abolish not the museum, but the curator: or at least the curator’s salary. Don José offered to serve in an honorary capacity; and as he had hoped a newly-elected council eventually gave him back his pay.

But these continual difficulties, the daily worry, overcame a man quite unsuited to cope with them: there was little that he could do, apart from offering to pay his rent with pictures, giving private lessons, and selling an occasional canvas. Fortunately his landlord was a lover of the arts, as they were understood in Málaga in the 1880s; or at least he liked the company of artists, and he accepted a large number of José Ruiz’s paintings. Several were found in his descendants’ possession some years ago; but it was thought kinder not to exhibit them.

Don José’s worries were real enough in all their sad banality, and many, many people can sympathize with them from experience; but there was also a factor that perhaps only another artist can fully appreciate in its full force. He was a painter; he was entirely committed to painting; and he was losing his faith in his talent—a few years later he gave up altogether. Whether he realized that his original vocation...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Preface to Original Edition

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- Keep Reading

- APPENDICES

- Index

- About the Author

- Also by the Author

- About the Publisher