eBook - ePub

About this book

Who are the world's best soldiers? Since the Iranian Embassy siege in 1980, the Falklands and the 1991 Gulf War, the British SAS have often been described as the greatest experts in Special Operations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access SAS and Other Special Forces by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Heroic Elite

Writing about 500BC in Imperial China, Sun Tzu Wu produced a book of military aphorisms which guided tactics and strategy in China for centuries and were adopted by Mao Tse Tung in his military writings in the 1940s. Centuries before the ‘Boss’ of a special forces patrol called his team together to discuss an upcoming operation in what the SAS call a ‘Chinese Parliament’, Sun Tzu had identified some of the principles of leadership which motivate soldiers, non commissioned officers (NCOs) and officers:

“The general who advances without coveting fame and retreats without fearing disgrace, whose only thought is to protect his country and do good service for his sovereign, is the jewel of the kingdom.

“Regard your soldiers as your children, and they will follow you wherever you may lead. Look on them as your own beloved sons, and they will stand by you even unto death”.

The operations undertaken by special forces succeed in part because they are well equipped and briefed, but also because the men have been carefully tested and selected and because they are led by men they trust, and who trust them.

Military history is full of examples of gifted, charismatic leaders who have attracted a small group of men — and sometimes women — who have achieved successes against greater numbers through a mixture of guile, surprise, courage and fighting skill. These men and their leaders are an elite.

Leadership alone will not win battles; equipment and training are the other two sides of a tripod which ensures success. Even the most courageous and successful soldier in special forces started as a nervous recruit. It was the tough but intelligent training, combined with their own motivation, that made them ‘special’. Superior equipment can include weapons, communications, transportation, and sensors and intelligence gathering equipment.

Biblical special forces

The Bible gives us a good example of special weapons, training, tactics and leadership with Joshua, Gideon and David. Gideon’s selection course and novel tactics are covered in the introduction to this book. Before Gideon’s operations, Joshua was leading the children of Israel from Egypt to occupy the Promised Land, “a land flowing with milk and honey”. He sent “two spies” on a long range reconnaissance patrol to check the land. These unnamed operators penetrated Jericho and found a “safe house” belonging to Rahab, “a harlot”. Rahab not only concealed them among drying flax on her roof, but facilitated their escape by rope over the city walls. She also struck a deal with them. When Jericho fell after a siege which included some ingenious ‘psychological operations’ it was “utterly destroyed... both man and woman, young and old, and ox and sheep and ass with the edge of the sword” in what would now be called ethnic cleansing, but Rahab and her family survived.

David’s use of a sling to stun the massive Philistine warrior Goliath around 1010BC is an excellent example of technology and training. With time on his hands as a shepherd, the young David had developed his skill with a sling to the level that he could send a golf ball sized pebble accurately at a target area the size of a man’s forehead. The sling might be new technology on the battlefield, but its effective use required a high level of training and skill.

The longbow – a technological advantage

Many centuries later King Henry V’s defeat of the French at Agincourt is a fascinating example of the king as charismatic leader; his Welsh bowmen the skilled technicians of war, expert with their weapons. The French had already suffered defeat at Crecy in 1346, when an English force of 10,000 defeated 24,000 French and Genoese. The French losses were 11 princes, 1,200 knights and 8,000 others. At Poitiers ten years later 7,000 English under King Edward and the charismatic Black Prince faced 18,000 French. By combining the shock effect of showers of arrows with a flank attack, the English routed the French — killing 8,000 and capturing the French King John II, who was ransomed for the massive sum of œ500,000.

In October 1415 a force of 9,000 tired and sick English and Welsh soldiers were confronted by a force of about 30,000 French under Constable d’Albert. The defensive position chosen by King Henry V funnelled the French heavy cavalry. The archers had also built a palisade of stakes which broke the charge of French men-at-arms. It was a harsh battle, with the Anglo Welsh force losing 130 and the French 5,000 killed, including the Constable and three dukes. A thousand prisoners were taken, including the Duke of Orleans and Marshal Jean Bouciqaut. When heavily armoured horses and men had been knocked down by arrows, the Welsh archers in a spirit of sanguinary democracy slipped out from behind the palisade to cut the throats of the immobilised French aristocracy. This was unpopular with the English aristocracy who not only felt a certain kinship, but also hoped to make some cash from ransoms.

The English and Welsh longbow was a weapon which, to be used effectively, demanded regular practice and considerable physical strength — a pull of over 100lbs (50kg) was required. War arrows recovered from the Mary Rose, which sank at Portsmouth in 1545, show a design which is close to that of a modern anti-tank (AT) round. The 3 foot (0.9 metre) shaft could be as thick as a .50” round, and was tipped with a sharp point — akin to a long rod penetrator in an AT round. This meant that enormous energy was focused into a small area, making it capable of penetrating armour.

Archers could adjust from dense long-range plunging fire — which fell among men and horses as they formed up and began their charge at 300 yards (274 metres) — to flat trajectory direct fire at 100 yards which would penetrate armour. A trained archer could fire ten rounds a minute, which meant that at Agincourt the 8,000 English and Welsh archers were putting 80,000 arrows a minute into the target area.

In ‘A History of the English Speaking People‘, Winston Churchill records that the longbow was more accurate than most muskets up to the American Civil War in the 1860s. During World War II there was even serious discussion about the effectiveness of the bow as a silent weapon for killing enemy sentries. However to be an effective archer it was necessary for a man to practise almost daily and the musket, even though it was crude, slow and inaccurate, could be fired by a simple conscript soldier with a minimum of training. New technology in the 15th Century included the Hussite War Wagons, which anticipated the function of armoured personnel carriers in the 20th Century, carrying infantry to battle in protected vehcles. Through the following centuries battles remained set piece actions, with infantry and field artillery holding the ground and cavalry providing the shock and manoeuvre element.

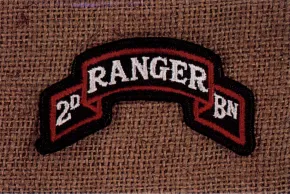

The shoulder tab for the 2nd Ranger Battalion

The Ranger tradition

Though European wars shaped military tactics and philosophy, a pointer to new tactics appeared in North America between 1754 and 1763 in King George’s War, also known as the French and Indian War. The Indian tribes with which the French and English had struck up alliances were excellent trackers, and used camouflage and sudden and violent ambush to defeat the medium-range firepower of muskets and the longer range of artillery.

The British were fortunate to have the services of Major Robert Rogers of Connecticut. Rogers’ Rangers operated against the French and Indians and adopted many of the techniques used by the Indians. His most famous operation was against the Abenaki Indians whose capital was at St Francis, forty miles south of Montreal. With a force of 200 Rangers travelling by canoe and cross-country, Rogers covered 400 miles in 60 days. Though they had suffered losses during the journey, they reached St Francis without the enemy being aware of their presence. On 29 September 1759 they launched their attack, killing several hundred Indians and finishing the Abenaki as a force. Rogers was later commissioned into the 60th Foot (The Royal Americans). His 28 standing orders for the Rangers have been refined into 19 and with few exceptions are just as relevant today:

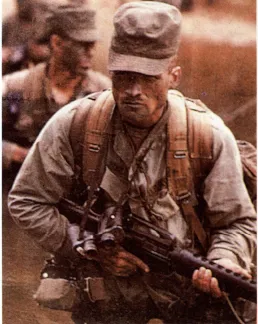

A Ranger radio operator on Grenada in 1983. His cap is shaped in the characteristic ‘Ranger Crush’. He is armed with an M16 rifle.

Rogers’ Rangers Standing Orders

1. Don’t forget nothing.

2. Have your musket clean as a whistle, hatchet scoured, sixty rounds powder and ball, and be ready to march at a minute’s warning.

3. When you’re on the march act the way you would if you was sneaking up on a deer. See the enemy first.

4. Tell the truth about what you see and what you do. There is an army depending on us for correct information. You can lie all you please when you tell the folks about the Rangers, but don’t never lie to a Ranger or an officer.

5. Don’t never take a chance you don’t have to.

6. When we’re on the march we march single file, far enough apart so one shot can’t go through two men.

7. If we strike swamps, or soft ground, we spread out abreast, so its hard to track us.

8. When we march, we keep moving till dark, so as to give the enemy the least possible chance at us.

9. When we camp, half the party stays awake while the other half sleeps.

10. If we take prisoners, we keep ‘em separate till we have time to examine them, so they can’t cook up a story between them.

11. Don’t ever march home the same way. Take a different route so you won’t be ambushed.

12. No matter whether we travel in big parties or small ones, each party has to keep a scout about 20 yards on each flank, and 20 yards in the rear, so the main body can’t be surprised and wiped out.

13. Every night you’ll be told where to meet if surrounded by a superior force.

14. Don’t sit down to eat without posting sentries.

15. Don’t sleep beyond dawn. Dawn’s when the French and Indians attack.

16. Don’t cross a river by a regular ford.

17. If somebody’s trailing you, make a circle, come back onto your own track, and ambush the folks that aim to ambush you.

18. Don’t stand up when the enemy’s coming against you. Kneel down, lie down, hide behind a tree.

19. Let the enemy come till he’s almost close enough to touch. Then let him have it and jump out and finish him off with your hatchet.

Rangers on patrol in a flooded area during a training exercise in the United States.

The name Ranger dates back to reports by American Colonist soldiers who would say “This day ranged nine miles”. Ranging meant travelling across some of the toughest terrain in the world. North America was a land of vast, thick forests, steep mountains and fast-flowing rivers, populated by hostile Indian tribes. The title Ranger has remained in the modern US Army.

Rangers fought for both sides during the Civil War and later in the M...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Heroic Elite

- Chapter 2: Special Air Service

- Chapter 3: The Cold War and Beyond

- Keep Reading

- Copyright

- About the Publisher