eBook - ePub

SS 1 EB

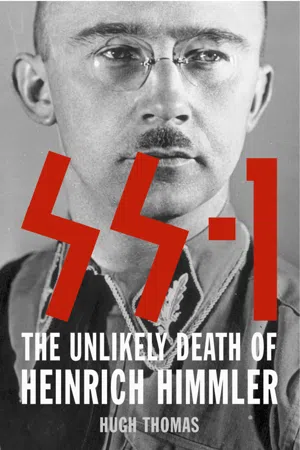

About this book

First serious examination of the curious demise of Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler that also investigates an extraordinary web of secret deals and international intrigue.

On 23 May 1945 Heinrich Himmler, leader of the SS and architect of the Holocaust, committed suicide in Allied custody. So why was MI6's most talented secret agent Kim Philby unconvinced by the story of Himmler's suicide?

Hugh Thomas set out to answer Philby's question and has uncovered a maze of corruption, high finance, political gambles and international intrigue.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Reincarnation and Exorcism

‘This whole case is regarded by the Allied Counterintelligence officers, and in particular by the British, as being the most important single case in the history of counterespionage.’

Unidentified officer, FBI files

In January 1946, in the fierce grip of winter, the defeated Reich had become a 143, 200-square-mile frozen madhouse. At the height of the Nazis’ power their empire stretched from the Atlantic coast of France to the outskirts of Moscow. Now Germany was half the size of France, with eight million refugees pouring in from the east to share the woes of 48 million citizens who were already confused, embittered and starving.

A proud empire lay dramatically humbled. Remnants of bridges were awash on her river banks. The stately Autobahns were pulverised by the treads of invading tanks. What little traffic there was picked its way laboriously along the smashed up roads, frequently stopping to let Allied convoys pass. Germany’s great cities reeked of sewage. Workmen toiled in tattered clothes while women formed endless chains to pass them bricks, working all day and through the icy night. As they struggled to restore some kind of order their children collapsed at school from malnutrition and cold.

At the centre of this devastation was Nuremberg: the scene of Hitler’s greatest triumphal rallies transformed into a grim stage for international retribution. The Albrecht Dürer Haus stood in glorious isolation amid the ruins. The bombed-out red shell, miraculously propped up by its central beam, presented a surreal landscape. As distinguished writer Rebecca West observed, Nuremberg in 1946 looked more like a woodcut by Dali than by Dürer. SS prisoners of war rebuilt the nearby Justizpalast at frantic speed. They continued to work throughout the marathon proceedings of the International Military Tribunal, which sat from November 1945 until mid-1948, looking for all the world like plaster-covered, maudlin clowns, wordless witnesses to their former leaders’ fates.

The Justizpalast had been adapted by the Nazis to achieve a level of efficiency that makes Henry Ford look prodigal. It housed twenty courtrooms; a penitentiary of meagre cells, each with a fifteen-inch window that denied any privacy; a prison yard, and a scaffold. In the glory days of the Third Reich, a man could be hauled in, charged, tried, convicted and hanged, all under one roof, before he had time to grow a six o’clock shadow.

In 1946 the Justizpalast was the showcase for a unique collection of Nazi nabobs. If it were possible to ignore the macabre nature of the proceedings, Nuremberg offered a great spectacle for the discerning viewer. British prosecuting counsel Lord Elwyn-Jones likened it to ‘a larger than life butterfly collection’.1 An imaginative court ruling that prisoners could choose their own clothing displayed the Third Reich’s ‘Superbia Germanorum’ in their finest colours. Every morning, fascinated American white-cap guards would assemble by the pear tree in the prison yard to watch the prisoners’ daily metamorphosis, emerging from their brown army-blankets to take their first hesitant steps along the 60-metre catwalk that led to the court. The blue admiral’s coat of Hitler’s chosen successor, Karl Dönitz, led the way, closely followed by former Minister-President Hermann Göring in dull cabbage-white leather. Then came Foreign Minister Konstantin von Neurath draped in full hunting furs, and Reich Youth Leader Baldur von Schirach in an expensive fur coat with a fetching sable collar. Grand Admiral Erich Räder swept behind them in a black, tightly-fitting, swallow-tailed Russian riding coat that his boyfriend had given him as he awaited trial in a Moscow dacha. Little wonder that a modestly dressed Albert Speer, who brought up the rear, hid under the hood of his anorak and was later to record his embarrassment.2 Each procession would climax in a flutter of activity as they hovered over individually named seats, before settling to bask under blazing lights on the squat rostrum in the middle of the court.

Anthony Marreco was to witness this ritual countless times.3 One of the British counsel for the prosecution, he was there to bring to justice members of allegedly criminal organisations, such as the Schutzstaffel (SS), the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), the Kriminalpolizei or Kripo, and the Geheime Staatspolizei (Secret State Police), unpopularly known as the Gestapo. Less openly, Marreco was also responsible for liaising between the Allied Secret Services and the judiciary. As the English and American intelligence agencies dominated proceedings to the exclusion of Russia and France, in effect he belonged to an exclusive Anglo-American club.

Marreco sensed the irony of seeing these men in the marble courtroom that had hosted the savage parodies of justice under National Socialism. How many helpless defendants had been condemned without pause by dour men in judicial robes tainted by swastika armbands? Now the Nuremberg trial judges sat before him, craning forward to avoid the freezing cold leather of their high-backed chairs. The emaciated figure of Chief Justice Robert H. Jackson, with his long, hairless head, hooded eyes and wrinkled neck, looked like a desiccated bald eagle perched in front of the stars and stripes of the American flag. In contrast stood German defending counsel Otto Kranzenbühler, an imposing man bolstered by self-importance and the ski suits under his robes.

Nobody had thought to restore the heating system; Nuremberg was a court sitting in refrigeration. People traipsed the aisles in ski boots. It looked as if everyone was talking animatedly; closer inspection revealed their soundless chatter resulted from the cold. Bulbs on the witness stand kept flashing yellow and red. Yellow meant ‘the interpreter is behind you, please slow down’, and red meant ‘stop’. As prisoners gave their evidence through clenched teeth, the constant interruptions led to the nickname ‘The Traffic Light Trial’.4

Marreco had taken the precaution of wearing not one, but two pairs of tights, as well as mittens. He clutched two files, each marked with red tabs that denoted ‘hands off – British interest’, as he sidled over to the window and pulled the brown curtain over his legs for extra warmth. He did not want to be distracted from the incredible impact that the subject of one of his files was making in the witness stand, a sight that would haunt him in later years.5 The high-ranking SS Brigadeführer spoke calmly and quietly, oozing a self-assurance that was as repelling as it was fascinating. He leant forward with straightened arms in a manner that transformed the forbidding rostrum into a pulpit of light and reason. Marreco later recalled how ‘the spectre of bestiality and the aura of evil that was my especial responsibility at Nuremberg seemed, in his hands, to become a frank talk by a guest speaker at a Women’s Institute’.6

The Brigadeführer’s perplexing confidence brought gasps from hardened newsmen. Lord Elwyn-Jones described this gentlemanly display as ‘obscene legal pat-a-cake’.7 Marreco’s first reaction was to open his thin file, which he searched in vain for an explanation. Surely this Brigadeführer knew his words condemned him as much as they did his former colleagues, however much he sought to exonerate himself. If a deal had been struck, the documents that identified this man to be of ‘British Special Interest’ gave no hint of it. Anthony Marreco was not alone in wondering whether the Brigadeführer had come to some secret arrangement with the Allies. In the closing days of December 1945 the same thought had seared the tortured mind of the huge figure that peered out of his Nuremberg cell through eyes that were filled with hatred.

Himmler’s deputy, Obergruppenführer Ernst Kaltenbrunner, had become a convenient focus of loathing for the world’s media. It was as if the evil of Nazism had been made flesh. When he sat in the dock he dwarfed his co-defendants. Kaltenbrunner’s disproportionately small hands were deeply nicotine-stained and armed with claw-like black finger nails that had made even Himmler cringe. A livid scar scored the left side of his white, pitted face, curling every attempted smile into a snarl. But the fear Kaltenbrunner’s appearance induced in others was nothing in comparison with the encroaching terror he felt as the trial proceeded.

When the Brigadeführer made his initial appearance at court in November 1945 he had expertly explained the structure and role of the SS, and his status within it, in a way that minimised their role in the holocaust and other atrocities. Impressed, initially Kaltenbrunner asked for him to be a witness for his defence. It was a grave error. For all the Brigadeführer’s fine words, it soon became apparent that he was no better than a covert witness for the prosecution, each delicate phrase another nail in Kaltenbrunner’s coffin. By the first week of January 1946 Kaltenbrunner suffered a fine tremor in his hands. We can only imagine how painfully they were clenched as he watched the Brigadeführer being inexplicably cosseted by the Allies. He was so depressed by the performance that he complained to Albert Speer that he would ‘only have needed a few seconds to wring the man’s scrawny neck’.8

A clue to the Brigadeführer’s special status was soon to come. It was still dark when Ralph Boursot, temporary legal clerk to the trial, began what he liked to call his early morning ‘paper round’. Every day he would check the details of new prisoners in the penitentiary.9 Boursot was up in time to watch two Queen Alexandra nurses tuck the Brigadeführer into a wheelchair and cover him with blankets. If that was not enough, he was wearing a black silk scarf and a long black Crombie coat bought at Savile Row in London before he came to Nuremberg. The legal clerk was not the only one watching this well-dressed man enjoy the touching solicitude of the British and Americans. Few prisoners truly slept at Nuremberg. Imagine how many suspicious eyes bored into the Brigadeführer’s back, wondering where he was going at such an early hour with the British Intelligence officer who never left his side. A groan of envy came from somewhere on the first floor as a large stone hot-water bottle wrapped in blankets was delicately placed in his lap.

The small party was ushered out of the penitentiary in style by Fielding, the noisy American white cap guard from the first division who amused himself by stomping around the echoing building in jack-booted fashion.10 Their departure did not even elicit comment from Göring in the cell opposite, who was known for his ready supply of sarcastic remarks.11 As several of the more perceptive Nazi leaders imprisoned at Nuremberg recognised, the ‘British Interest’ card was being brazenly played in the middle of an international tribunal that was supposed to be dispensing justice.12 Envy kept them silent.

In the early hours of that same morning Major Norman Whittaker was greeted by darkness and fine snow when he landed at Bückeburg airport. He arrived at a Hannover mess before the kitchens were opened and was driven off before breakfast by two corporals. Now he was waiting in the slanting light of Lüneburg forest. His meticulously neat moustache was half-frozen to give him a stiff upper lip that hardly reflected his earthy Lancastrian sentiments, as later related to a fellow intelligence officer at Monty’s select ‘C mess’ (the ‘Creully Club’, named after the site where the intelligence group landed in France).13 When a civilian finally appeared in his jeep, an hour late, Whittaker’s feet were numb. Such a predicament would normally guarantee an outburst. But Whittaker was unusually quiet – because he was unusually and acutely embarrassed.

He had felt smug when he left the War Ministry in London. After all, the details he had given on the map denoting Himmler’s grave ‘were perfectly adequate for a moron, let alone the Ministry’ to see at a glance exactly where the body was buried.14 Whittaker, who had been demobbed in August 1945, was secretly delighted to be involved in this hush-hush Himmler business again, but the cold made him regret his presence, unnecessary as it was. Not that his self-confidence was dented. Before the jeep arrived he had been lecturing his companions on the exact use of map co-ordinates and descriptions. As soon as he had led its occupants up the track he had found so easily, he realised just how misplaced his confidence had been. It should have been easy. Only seven months earlier he had been driving in a similar jeep, squashed against his bulky chain-smoking Colour Sergeant Major Edwin Austin, followed by a Bedford truck driven by Sergeant Ray Weston, with poor Sergeant Bill Ottery stuck in the back, gagging over a corpse.

Back in May they too had set off before sunrise on their secret mission to dispose of the body of Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler. With their lights dipped, they left the car park behind 31a Ülzenerstrasse, drove down the rear of the street, and turned right back into Ülzenerstrasse, passing the house they had just left. What was supposed to have been a quick, efficient disposal mission soon descended into farce. As Whittaker put it, ‘It was a hell of a job to find a lonely spot’.15 They drove south out of Lüneburg and into the heath along the main Ülzen road, but although it was strewn with abandoned vehicles and it was still early in the morning, there were too many people around for comfort. The convoy turned off on to a quieter road leading to the north-east. This was too exposed, so they continued until they reached another main road, which they followed for some time without finding the cover necessary for their task. It did not help matters that it was so dark they could not see beyond the side of the road. Worse still, they did not possess an accurate, large-scale map. Whoever had drawn the one they had appeared to have marked Lüneburg after a particularly heavy drinking session. They stopped twice to reconnoitre possible sites, but neither seemed safe from scrutiny. It was so frustrating that they had driven a good part of the way back to Lüneburg before they finally discovered a spot where an old farm track joined the road obliquely from a slight incline. At least here was an opportunity to park their vehicles out of sight. Whittaker and Ottery jumped out to see where the track led.

Back in May it had seemed the perfect spot. There was a copse of trees that would screen them from prying eyes and the ground there ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1: Reincarnation and Exorcism

- 2: SS 1

- 3: The Vengeful Chameleon

- 4: The SS State

- 5: Peace

- 6: The Stockholm Connection

- 7: The Maison Rouge Meeting

- 8: Loose Ends

- 9: Preparations for Survival

- 10: The Arrest of Heinrich Hitzinger

- 11: Operation Globetrotter

- 12: Doubt

- 13: Sonderbevollmächtigter – the ‘plenipotentiary extraordinary’

- Appendix: The contribution of computer technology

- Index

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Notes

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access SS 1 EB by Hugh Thomas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.