- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Siege of Leningrad: History in an Hour

About this book

Love history? Know your stuff with History in an Hour.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Siege of Leningrad: History in an Hour by Rupert Colley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Russian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Appendix 1: Key Players

Andrei Zhdanov 1896–1948

Born 26 February 1896, Andrei Zhdanov was typical of Joseph Stalin’s inner circle: mendacious, ruthless, indifferent to the fortunes of the ordinary citizen, but, answerable only to Stalin, utterly fearful lest he should ever fall out of favour. For this, in common with all members of the sycophant Politburo, Zhdanov put the interests of Stalin ahead of all else.

The Yugoslav writer, Milovan Djilas, described Zhdanov as ‘rather short, with a brownish clipped moustache, a high forehead, pointed noise and a sickly, red face’. Speaking at the inaugural Union of Writers Congress in 1934, Zhdanov emphasized the need for Soviet writing to adhere to the strict guidelines of Socialist Realism, a form of realist art that depicted Stalin’s Soviet Union in a positive, utopian manner. From this, and under Stalin’s guidance, Zhdanov formulated a policy for the straitjacketing of the arts within the Soviet Union. The ‘Zhdanov Doctrine’ dictated that all forms of cultural expression, from science and philosophy to music and cinema, had to strictly adhere to State control and reject all forms of Western influence or ‘cosmopolitanism’.

Zhdanov was promoted as head of the Leningrad Party following the assassination of his predecessor, Sergei Kirov on 1 December 1934. His first task in the city was to root out deviationists and potential troublemakers, and ensure that the city was unbending in its loyalty to Stalin. The Polish-born journalist and writer, Isaac Deutscher, described Zhdanov as a ‘capable, and ruthless man . . . Stalin could rely upon him to destroy the hornet’s nest in Leningrad.’

During the war, Zhdanov led the civil defence of Leningrad throughout its 872-day siege in partnership with a succession of military commanders, at least for the first few months, with the city’s military commander, Kliment Voroshilov. Following the war, Zhdanov enjoyed the height of his power and, tipped to be Stalin’s successor, was known as ‘Stalin’s firm favourite’. His very success and eminence may have prompted the beginnings of his downfall – Stalin was never one to forgive another’s fame if it threatened his own.

Post-war, Zhdanov renewed his attack on the artistic community. Dmitri Shostakovich, who had enjoyed a period of State acceptance during the siege of Leningrad, was particularly targeted; as was Anna Akhamtova, Russia’s leading poet, whom Zhdanov described as a ‘whore and a nun’ and a ‘slimy literary rogue’. An alcoholic, he suffered a number of heart attacks and in July 1948, was relieved from his duties to give him time to recuperate. By then his star had waned and, due to his continual drinking, he had fallen out of Stalin’s favour. This in itself may have contributed to his drinking. He died, aged fifty-two, on 31 August 1948. The circumstances surrounding his death have been shrouded in mystery, and although Zhdanov probably did die of another heart attack, rumours persisted that he had outlived his usefulness and that Stalin had a hand in his demise.

His death salvaged his reputation and immediately he became an icon of Soviet worship. Towns and streets throughout the Soviet Union were renamed in Zhdanov’s honour. The Ukrainian town of Mariupol, Zhdanov’s place of birth, was renamed Zhdanov, only returning to its original name in 1989.

In 1952, four years after Zhdanov’s death, Stalin launched his purge against doctors, the Doctors’ Plot, accusing leading physicians of malpractice. Zhdanov, it was claimed, was victim to one such incident of medical foul play. Following his death, Zhdanov’s former Leningrad associates and supporters were targeted in another of Stalin’s purges. Harbouring a lifelong dislike of the city, Stalin purged over 2,000 of the city leaders, artists, writers, and intelligentsia in what became known as the ‘Leningrad Affair’.

Zhdanov’s son, Yuri, married Stalin’s daughter, Svetlana Alliluyeva, in 1949, but the marriage ended in divorce in 1952. Even Yuri Zhdanov had to write a letter of self-criticism, begging forgiveness for his supposed professional misdeeds, and published for all to see in the Soviet newspaper, Pravda.

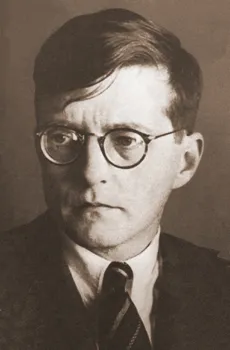

Dmitry Shostakovich 1906–1975

A child prodigy, Shostakovich completed the first of his fifteen symphonies at the age of nineteen. During the early years of Stalin’s rule, he and fellow artists enjoyed a period of creative freedom but Stalin brought this period to an abrupt end in 1932 when all forms of avant-garde creativity were banned.

It was in 1932 that Shostakovich’s second opera, Lady Macbeth of the Mtsenk District, was first performed to gushing reviews. It survived for four years enjoying unqualified success until, at the height of the Great Terror in 1936, Stalin decided to attend a performance. Shostakovich was in the audience and from the corner of his eye, watched in horror at the expressions of distaste on the dictator’s face. Obliged to take a bow at the end of the performance, Shostakovich looked ‘as white as a sheet’. Within days, a review appeared in Pravda entitled ‘Muddle Instead of Music’, widely believed to have been penned by Stalin himself: ‘Snatches of melody, the beginnings of a musical phrase, are drowned, emerge again, and disappear in a grinding and squealing roar. To follow this "music" is most difficult; to remember it, impossible.’

The opera was immediately withdrawn and reassessed. The authors of rave reviews now rushed to publish revised reviews condemning the work and apologizing for failing to see its inadequacies first time round. Shostakovich’s fall from grace was spectacular. Labelled an enemy of the people, and with his works banned, he fully expected to be arrested at any moment and reportedly slept fully clothed with a packed suitcase at hand.

In his next work, Symphony No. 5, subtitled, A Soviet Artist’s Practical Creative Reply To Just Criticism (1937), Shostakovich fell over himself to tow the official line and through it he managed to salvage his reputation and ensure his survival.

With the outbreak of war in 1941, Shostakovich, living in Leningrad, tried to enlist for the Red Army but was rejected because of his poor eyesight. Instead, he volunteered for the fire brigade and, at the same time, started work on his Seventh Symphony. He had completed the first three movements when, together with his family, he was ordered out of the city. Evacuated to Kuibyshev, he completed the work on 27 December 1941. The Leningrad Symphony, as it became known, brought him back into favour. Dedicated to the city, it was, according to Shostakovich, written as a condemnation of Hitler’s tyranny but, in later years, he admitted it was against Totalitarianism as a whole, including that of Stalin.

Following the war, Shostakovich suffered a second denunciation when Andrei Zhdanov, the former Party leader in Leningrad, launched a policy of artistic tightening rejecting all Western influences within Soviet art. Known as the ‘Zhdanov Doctrine’, Shostakovich’s work was again banned and labelled as ‘anti-people music’, and Shostakovich was forced to publicly recant his ‘mistakes’. Again, fearing arrest, Shostakovich composed a number of film scores and pieces of music deemed suitable for the regime. In one, a cantata entitled ‘Song of the Forests’, he referred to Stalin as the ‘great gardener’. It won him a Stalin prize and 100,000 rubles.

Following Stalin’s death in 1953, Shostakovich enjoyed another revival of his fortunes. In 1960, in an attempt to appease the regime, he joined the Communist Party, although he felt shamed by it and later told his wife he had been ‘blackmailed’ into it. In 1962, he married for the third time to a woman twenty-nine years his junior. In 1965 he was diagnosed as having polio and suffered his first heart attack.

Shostakovich’s other obsession, besides music, was football. A devoted fan of his local team, Zenit Leningrad, and a qualified football referee, he was according to the Soviet writer, Maxim Gorky, ‘a rabid fan. He comported himself like a little boy, leapt up, screamed and gesticulated’ during matches. A lifelong chain smoker, Shostakovich died of lung cancer on 9 August 1975 – exactly thirty-three years after the Leningrad première of his most enduring work.

Georgi Zhukov 1896–1974

Georgi Zhukov achieved fame as perhaps the most famous Soviet military commander of the Second World War. In the post-war Victory Parade in Moscow’s Red Square, Zhukov stole the show, inspecting the troops mounted on a white stallion. Adored by the public and respected by international opinion, Zhukov’s position was always going to be vulnerable given Stalin’s innate jealousy. Sure enough, in 1946, Zhukov, heavily criticized for being ‘politically unreliable’, was dismissed and dispatched to a position of diminished responsibility in Odessa. On arrival, he suffered a heart attack, probably brought on by the stress of his ordeal.

RIA Novosti archive, image #2410 / P. Bernstein / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Known for his uncompromising discipline, Zhukov placed strategic objective far above the safety of the men he put into battle. Yet, despite his toughness, he could be rendered a wreck by a single harsh word from Stalin. During the early days of the war, he was once reduced to tears by an angry Stalin.

Zhukov first saw action during the First World War, where, renowned for his bravery, he was twice decorated. He then fought with the Red Army against the Whites during the Russian Civil War of 1917–23 and quickly rose through the ranks. He survived Stalin’s great purge of the military to command an army during the Soviet-Japanese Border Wars of 1938–39. He played a major role during the Great Patriotic War, commanding forces in the defence of Leningrad, Moscow, and Stalingrad, played an albeit minor role in the Battle of Kursk, and led an army into Germany and Berlin. ‘Where you find Zhukov, you find victory,’ became a popular saying within the Red Army. He was present when, following Hitler’s suicide, Germany surrendered to the Soviet Union.

Following Stalin’s death in 1953, Zhukov helped Nikita Khrushchev to power, arresting Lavrenti Beria, Khrushchev’s main rival. Beria was executed in December 1953 and with Khrushchev now in power, Zhukov was called back to the Kremlin as Deputy Defence Minister, elevated two years later to Defence Minister. However, Zhukov was never comfortable as a politician, much preferring the life of a soldier. He argued with Khrushchev’s vision of how the military should be developed and tried to diminish the Politburo’s influence on how the military was run. Zhukov was again sidelined and dismissed in 1957. Zhukov died in 1974 and was buried within the Kremlin Wall with full military honours.

Kliment Voroshilov 1881–1969

Kliment Voroshilov saw action during both the Bolshevik Revolution and the Russian Civil War that followed, and, working closely with Stalin, gained a reputation for his fierce defence of Tsaritsyn (renamed Stalingrad in 1925).

In 192...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- About History in an Hour

- Contents

- Introduction

- The History of Leningrad

- The Great Patriotic War

- Preparing the City for War

- Evacuation

- The German Advance

- The Men in Charge

- Under Attack

- Hunger

- Death in a Cold City

- The Road of Life

- Spring 1942

- The Symphony

- Leningrad Liberated

- The Aftermath

- Appendix 1: Key Players

- Appendix 2: Timeline of Siege of Leningrad

- Copyright

- Got Another Hour?

- About the Publisher