- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

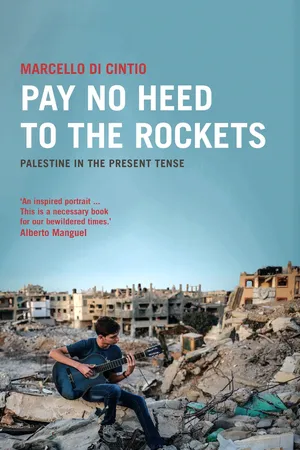

Across Palestine, from the Allenby Bridge and Ramallah, to Jerusalem and Gaza, Marcello Di Cintio has met with writers, poets, librarians, booksellers and readers, finding extraordinary stories in every corner. Stories of how revolutionary writing is smuggled from the Naqab Prison; about what it is like to write with only two hours of electricity each day; and stories from the Gallery Cafe, whose opening three thousand creative intellectuals gathered to celebrate. Pay No Heed to the Rockets offers a window into the literary heritage of Palestine that transcends the narrow language of conflict. Paying homage to the memory of literary giants like Mahmoud Darwish and Ghassan Kanafani and the contemporary authors they continue to inspire, this evocative, lyrical journey shares both the anguish and inspiration of Palestinian writers at work today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pay No Heed to the Rockets by Marcello Di Cintio in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & Literary Collections. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Exporter of Oranges and Short Stories

In Gaza

I wanted to visit Gaza because all I knew of the place came from reports of cruelty, death and destruction. Gaza is one of the world’s most overcrowded places. The 2016 birth of a boy named Waleed Shaath bumped the population of this tiny finger of land – forty kilometres long and only six kilometres wide at its narrowest point – to two million souls. But Gaza is more often defined by tragedy than the statistics of geography. The territory stands as a physical embodiment of despair. Gaza is where rockets fly and buildings fall and children die. There is no word imbued with less beauty than Gaza. No word less poetic. Gaza is the buzz of fighter jets tearing the sky. Gaza is the drone of a drone.

Plutarch, though, named Gaza aromatophora – the dispenser of perfumes. Mahmoud Darwish wrote that Gaza ‘is the most beautiful among us, the purest, the richest, and most worthy of love.’ Gaza lies along the Mediterranean Sea, after all. There must be more to this ancient sliver of coastline than rubble and ruin.

I hired a taxi to bring me from the nearby city of Asqalan to the Erez chekpoint, the main entry point into Gaza. I arrived at eight thirty in the morning but the soldier at the gate said the checkpoint was closed. ‘Maybe it will open at ten o’clock,’ she shrugged. It didn’t. The gate finally slid open at noon and I entered the Israeli border post, a bright and clean building laid with polished tile. The feeling of welcome startled me. The place resembled the arrivals lounge at Ben Gurion airport in Tel Aviv.

The checkpoint’s aesthetics of hospitality faded once I showed my documents to a soldier in a glass booth and navigated the gauntlet of security architecture behind her. I followed a yellow arrow and a sign reading, simply, ‘Gaza’ in Hebrew, English and Arabic and went through a door. More yellow arrows led me into a tight passageway flanked with high steel walls. I wrestled my backpack through the metal turnstile at the end of the hall then walked across a fenced outdoor courtyard to another turnstile built into a gate of vertical bars. The entire labyrinth reminded me of the checkpoints at Qalandiya. Only here at Erez no press of bodies struggled to get through. I was completely alone. According to the Israeli agency COGAT (Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories), hundreds of Palestinians pass through Erez each day. But for all I could tell, I was the only person entering Gaza that afternoon.

Once I clanked through the turnstile, I faced the wall of the grey concrete slabs forming Israel’s security barrier around Gaza. A thick steel panel at the base of the wall rumbled eerily to the side, remotely triggered by someone watching me through a security camera, revealing a small opening in the wall. Sunlight poured through. This was the door to Gaza.

I first learned of the Karawan Café from The Drone Eats with Me, Atef Abu Saif’s diary of 2014’s Operation Protective Edge. Atef writes of coming to the café from his home in the Jabaliya refugee camp every morning for seventeen years and the importance of keeping up his daily routine in the midst of war. ‘We have to recapture some normality, to reclaim some of the life we had before,’ Atef writes. ‘The Karawan Café is a very important ingredient of this normality.’ I was pleased, then, when Atef suggested we meet at Karawan. We sat outside the front door with our coffees while traffic noise from the nearby Saraya junction filled the spaces in between our conversation.

Atef never intended his journals from the war to become a book. On the fourth day, his UK editor sent him an email to ask how he was doing. In reply, Atef translated what he’d written in his journal into English and sent it to his editor, who in turn posted the journal entry on the publisher’s website. Atef liked the idea of people outside Gaza reading his account of the war, so he started writing his daily journals in English and sending them to London. Atef didn’t know that his editor was also passing the entries along to newspapers, such as the New York Times, the Guardian, and the Sunday Times, which were reprinting them. ‘During the war, sometimes we only had electricity for two hours. I would use those two hours just to write my diaries, so I wouldn’t check the internet,’ he said. Occasionally, Atef walked to the camp’s internet café to write on its computers because it had a generator. The café owner knew Atef and chased out the children playing video games. ‘He would say to them, “Leave mister to work,” then he would lock the door until I finished my story.’

Atef derived no pleasure from writing his war diaries, but he considered them necessary. During the two previous wars in Gaza – Operation Cast Lead in 2008 and Operation Pillar of Defense in 2012 – Gazans knew places where they could feel safe from the Israeli bombing runs. They waited out the fighting in the homes of friends and family who lived in neighbourhoods they figured would be spared. But nowhere felt safe in 2014. The destruction was widespread. Everyone I spoke to about Protective Edge told me the same thing: they never knew if they would see another day. ‘The action of writing is a testimony of my survival,’ Atef said. ‘When I am writing, I am proving that I am alive.’

Atef also felt compelled to tell stories that the journalists sent to cover the war refused to tell. ‘I wanted to get out the humanity which war wants you to lose,’ he said. Atef describes how his family endured the fifty days of fighting and struggled to observe Gaza’s Ramadan traditions during the bombings. He writes about how his son just wanted to go to the internet café to play football games, and about a distraught man living in a UN-run shelter who begged for a few minutes of privacy to make love to his wife. In the media, Gazans appear as mere pieces of news. Atef wants to make them pieces of literature. That way they last forever.

In the footnotes of Drone, Atef gives the full names and ages of those killed in the fighting. The long list of victims, often members of the same family, challenges the sterile statistics of conventional war reporting. This was another of Atef’s intentions: to honour those lives that, through their ending, have been reduced to numbers. Atef writes:

When a human being is made into a number, his or her story disappears. Every number is a tale; every martyr is a tale, a life lost … The Kawareh family – from Khan Younis, whom the drone decided to prevent from enjoying a meal on the roof of their small building under the moonlight – they were not just ‘SIX.’ They were six infinitely rich, infinitely unknowable stories that came to a stop when a dumb missile fell from a drone and tore their bodies apart. Six novels that Mahfouz, Dickens or Marquez could not have written satisfactorily. Novels that would have needed a miracle, a genius, to find the structure and poetry they deserved. Instead, they are tales that have cascaded into the news as numbers: moments of lust; onslaughts of pain; days of happiness; dreams that were postponed; looks, glances, feelings, secrets … Every number is a world in itself.

Atef does not write about Hamas in Drone, nor about the rockets they sent over the border into Israel, which many observers blamed for the Israeli airstrikes. I asked him if this was a deliberate omission. ‘I am not reporting on the war,’ Atef said. ‘I am writing from the perspective of a family. A family that is besieged and being attacked. Feeling that they might die suddenly. Feeling like they don’t belong to the minute. Things happen out of their control and they want to bring order to their little world. Their little living room. Their little kitchen. The rockets are always in the background, but it’s not me who can write about them.’

The Drone Eats with Me is something of a departure for Atef. He is best known as a writer of short stories, a genre particularly associated with Gaza’s unique geopolitical history. Many of Gaza’s writers fled after the 1967 war and the literary scene collapsed under the weight of occupation. Israeli authorities shut down all the printing presses in Gaza to cripple communication between Palestinian resistance groups. Gazan novelists had no way to publish their work. Young writers, not to be defeated, started to write short stories and novellas, which were more easily hand copied and smuggled to Jerusalem where they could be published. According to Atef, Palestinian literary circles once knew Gaza as ‘the exporter of oranges and short stories.’ Few oranges leave the territory these days, and Gaza now boasts a wealth of writers in all genres, but the short story remains a Gazan specialty.

Atef’s parents and grandparents fled their home and orange orchards in Jaffa in 1948 and settled in Gaza City’s Jabaliya refugee camp. Atef was born in the camp in 1973. By then the camp, like all Palestinian refugee camps, had grown from a collection of tents into a crowded ghetto of cinderblock buildings. Atef always longed for Jaffa, even as a boy, and named his daughter after the city his family was forced to abandon. ‘For Palestinians, Jaffa is the lost dream,’ Atef said. ‘When Palestinians talk about the Nakba, they talk about Jaffa, because it was one of the biggest Arab cities at the time. It was the second most important cultural hub after Cairo.’ Before 1948, Jaffa’s newspapers were published throughout the Arab world and the city hosted the second-largest Arab radio channel. ‘If you were a big singer you had to come to Jaffa to sing.’

Atef learned about Jaffa from his blind grandmother, Aisha. ‘She lost her ability to see because she cried too much for her son, who died in the war,’ he said. When he was a boy, Atef used to sit with his grandmother and listen to her endless stories – many about her youth in Jaffa. Atef believed that she would have been a great novelist. ‘She could take your heart for five hours,’ Atef said. ‘Her way of telling stories was brilliant, and I hope by the end of my life I can manage to tell stories like she used to.’

When he was ten years old, Atef started writing his grandmother’s stories down. Once the First Intifada began in 1987, he began to write his own. ‘I was a very naughty boy at that time,’ Atef said. He and his friends used to hurl stones at Israeli soldiers at the military checkpoints. During one of these clashes, an IDF soldier shot Atef in the face with a rubber bullet. The wounds were severe. ‘I was supposed to die,’ he said. ‘My family even dug a grave for me.’ Atef recovered and continued his actions against the IDF at the checkpoints. He was eventually arrested and jailed for three months in an Israeli prison in the Negev Desert.

Atef realises that many of his readers, both in Palestine and abroad, expect his work to be overtly political. ‘People are not ready to listen to you if you are not talking about wars or Hamas,’ he said. But for Atef, who was born in Gaza and still lives in Jabaliya’s narrow alleyways with his wife and children, Gaza is no metaphor. ‘Gaza is not only a place that produces news. It produces life as well.’ Gazans don’t want to read shouted refrains of resistance or vows to survive in the face of the siege. They want to read stories.

In addition to The Drone Eats with Me, Atef has published five novels and two books of short stories along with several books of political writing. He also edited and contributed to an anthology of Gazan short stories called The Book of Gaza: A City in Short Fiction. Atef’s last novel, A Suspended Life, was shortlisted for the prestigious 2015 International Prize for Arabic Fiction, known by many as the Arab Booker. Atef wanted to attend the award ceremony in Casablanca, but Hamas authorities stopped him at the Erez checkpoint and denied him an exit permit. In response, Atef penned a long screed against Hamas. He accused the authority of silencing artistic expression and contributing nothing to cultural life in Gaza since coming to power in 2007. ‘How many books has Hamas printed?’ Atef wrote. ‘How many literary festivals has it sponsored and organised? … How much talent was nurtured? How many cinemas have been built? How many literary competitions were held to strengthen the contemporary literary scene?’ Public support for Atef compelled Hamas to relent, but not in time. He never made it to Casablanca.

The award itself meant little to Atef. ‘I don’t need anyone to clap for me,’ he said. The only audience Atef cares about is his storytelling grandmother, Aisha. ‘One of my dreams is that I write a novel so good that my grandmother will come from out of her grave to enjoy it.’

Lara, my soft-voiced translator, was one of the few people I knew in Gaza who was not descended from refugees. Her family were true Ghazzawis who lived in Gaza long before the Nakba. At twenty-three years old, she is already a professor of war. Lara can identify Israeli ordnance by the different ways the ground shakes after each explosion. The first interview Lara translated for me was with author Gharib Asqalani. He welcomed Lara and me into his home on the edge of the Shati refugee camp. Like every Palestinian whose home I visited, Gharib offered us coffee. But instead of making some himself, he directed Lara to the kitchen. ‘There is the pot on the sink and the coffee on the shelf,’ he said to her. Lara shot me a look of bemused irritation but dutifully stood to make our coffee.

Gharib is hardly a humble man. He believes his life in Gaza was more complicated and nuanced than that of the new generation of Gazan writers. ‘I’ve experienced things they have only read about in books,’ he said, adding that they concern themselves with winning prizes and writing for foreigners. He was still an infant in 1948 when Israeli soldiers swept through what was then known as the Gaza subdistrict. The occupation forces emptied forty-five out of fifty-six towns and villages in the area, including al-Majdal Asqalan, where Gharib had been born a few months earlier. He and his family escaped into the Gaza Strip along with the more than 200,000 refugees who sought sanctuary among Gaza’s 80,000 residents. Gaza swelled. The territory represented only one-hundredth of the area of Mandate Palestine but housed a quarter of the Palestinian population after the war. One historian wrote that Gaza had become ‘an involuntary Noah’s Ark.’

Like many Palestinian adolescents in the 1950s, Gharib grew up reading the works of Marx and Engels, but this leftist philosophy made little sense to Gharib as a young Gazan refugee. ‘In the camps, I didn’t see the rich living on the blood of the poor as Marx described,’ Gharib said. ‘Here the rich and poor were both expelled from their land. And there was no work for anyone.’

Gharib’s father, though, knew how to create work. He purchased a small plot of land near the Bureij refugee camp and planted strawberries and orange trees. He urged Gharib to study agriculture. Gharib agreed and travelled to Egypt in 1965 to study agricultural engineering at the University of Alexandria. Gharib had completed only his second year when Israel occupied Gaza in 1967. His family could no longer export their oranges and the Israelis restricted the amount of water allocated to the farm. Gharib’s father uprooted the orange groves and planted olive trees in their place. He knew olives could survive the d...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Maps

- Introduction

- Plucking Your Thorns with Your Hands, In Exile

- Whenever My Sore Heart Gets Hungry, In Ramallah

- This is Real Struggle, In Nablus

- Steadfastness, On the Land

- I Almost Don’t Fear the Sirens, In Jerusalem

- I Make Love in Arabic, The 48

- The Exporter of Oranges and Short Stories, In Gaza

- The Girl in the Green Dress, In Nuseirat Refugee Camp

- Sources

- Acknowledgments