- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

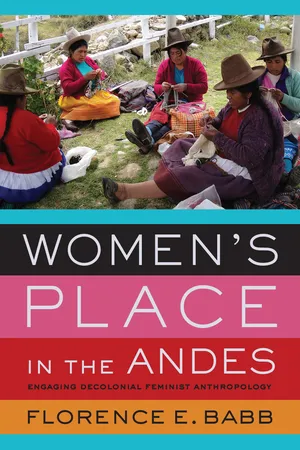

About this book

In Women's Place in the Andes Florence E. Babb draws on four decades of anthropological research to reexamine the complex interworkings of gender, race, and indigeneity in Peru and beyond. She deftly interweaves five new analytical chapters with six of her previously published works that exemplify currents in feminist anthropology and activism. Babb argues that decolonizing feminism and engaging more fully with interlocutors from the South will lead to a deeper understanding of the iconic Andean women who are subjects of both national pride and everyday scorn. This book's novel approach goes on to set forth a collaborative methodology for rethinking gender and race in the Americas.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Women's Place in the Andes by Florence E. Babb in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Gender and Rural Development

THE VICOS PROJECT

Commentary

My monograph on the applied anthropology project in the Andean community of Vicos, Peru, originally was written as a master’s thesis (1976) and, once revised, was my first published work (in various incarnations, Babb 1976, 1980a, 1985b, and, in Spanish translation, 1999). Presented as the sole entry in part 1, “Women and Men in Vicos, Peru: A Case of Unequal Development” was read in its several versions by a fairly specialized group interested in the anthropology of Peru and in gender and development in Latin America, and it did not have as broad a reach as might be expected. This may be because it did not appear in a high-profile venue and because of its chilly reception by those who were closest to the project.

The work created something of a disturbance among at least a few of the Cornell-Peru Project (CPP) personnel, who nonetheless remained publicly silent regarding the gendered implications of the applied anthropology initiative. I was gratified, however, to find that feminist scholars embraced the work and found it insightful or provocative, depending on their own perspectives. What I find particularly useful at this remove from the project’s history and from my own writing about it is to revisit what made my intervention challenging to some and generative to the thinking of others. Most significantly to my current endeavor, I assess here how the monograph engaged with the pioneering works in the field of gender and development, and how it participated in some of the earliest debates on Andean women. My discussion also anticipates how my work lends itself to a decolonial feminism.

I begin by setting the Vicos Project in its historical context of mid-twentieth-century anthropology and as a collaboration between scholars from the United States and Peru. Much of that story appears in my work that follows, so here I will be brief. When Cornell anthropologist Allan Holmberg took the opportunity to lease the Hacienda Vicos in 1952 and worked with a team of US and Peruvian social scientists to conduct an ambitious experiment in guided social change, it was in the context of both the Cold War and fledgling applied anthropology. Modernization theory underpinned the dominant paradigm for understanding social problems such as underdevelopment, inequality, and what was perceived to be a slow pace of change. The anthropologists who participated in the project, introducing and documenting change, worked from the assumption that once Vicosinos experienced freedom from centuries of near-feudal conditions, became involved in self-governance, and enjoyed higher levels of education and better health care, they would enter the “modern” world. First, however, these indigenous peasants would need the assistance of the project to shake free of past practices, from subservient behavior in the company of mestizos to the use of traditional forms of agriculture. To that end, the CPP encouraged new forms of sociopolitical organization and technologies for working the land.

Not surprisingly, given the time period of the CPP (1952–62) and the orientation of anthropology during those years, the main targets of change were men, and most often younger men, rather than women or the senior men who had been the traditional authorities in the community. In the planned transition of power from former hacienda owners to community members, new skills and decision making were directed to those men identified as heads of households and potential leaders in Vicos.1 When my graduate school advisor, William Stein, suggested that the CPP archives at Cornell University might offer a treasure trove of material on issues relating to my growing interest in the area of gender and development, I made this my chosen research base for my master’s degree at SUNY Buffalo.

I spent much of summer 1975 in Ithaca, New York, in the uncomfortably cool basement of Olin Library, where the archives were housed. As predicted, I found a rich source of material that enabled me to produce a critical feminist assessment of what the CPP offered to Vicosinos—and what, for a variety of reasons, it appeared to overlook. Much of the material I found most intriguing was in the form of researchers’ fieldnotes recording everyday activities and events—not intended to be part of a gender analysis but often providing fairly unfiltered and candid accounts of men’s and women’s lives in the community during the years of the CPP. Thus, despite the greater attention to young men by the principal project personnel and the scant attention to women in the published material, the archives themselves tell another story.

Among the field researchers with notes in the archives were anthropologists from the United States and Peru who were closely connected with the project, as well as affiliates and students from US colleges carrying out summer research in Vicos. In the latter group, among those less central to the project, but who were nonetheless keen observers in the community, was, for example, Aida Milla Vázquez—wife of the principal Peruvian scholar with the CPP, Mario de Vázquez—who was carrying out a study of the socialization of children in Vicos. Milla de Vázquez offered sharply incisive commentary about the project at times, no doubt to the consternation of the CPP.2 Another notable participant was Harvard undergraduate Richard Price, whose fieldnotes impressed me as particularly sensitive and insightful; years later, I realized that he was the same Richard Price I knew as a prominent Caribbeanist anthropologist.3 Other student researchers whose fieldnotes were especially useful to my exploration of gender in Vicos were Norman Pava and Harold Skalka. It may have been precisely those with a lesser stake in promoting a positive image of the CPP who most freely described sensitive aspects of the planned intervention in social change.

My work that follows this commentary conveys more clearly what I learned from the archival materials. Here I turn to my work’s reception as well as its engagement with feminist debates of the time—and how I regard the work in light of more recent research and decolonial feminist theory.

THE LITERATURE ON VICOS AND THE SILENCE AROUND GENDER

In general, those who have heard of the Cornell-Peru Project believe that there has been an abundance of attention to Vicos. However, those most familiar with the CPP know that since the time of the project, most of the attention has been in the form of brief reports, popular press coverage, and numerous textbook citations of Vicos and the CPP as a model for applied anthropology. Of scholarly treatments there have been relatively few, including several unpublished doctoral dissertations, a number of journal articles, and several books, including two coedited volumes on Vicos that were published forty years apart.

Mario Vázquez (1961) wrote a concise book of fewer than sixty pages as a reference on hacienda communities in the Peruvian Andes and later published a fuller monograph (1965) on changes in schooling in Vicos from the arrival of the CPP through the mid-1960s. The key edited collection of contributions, mainly by CPP personnel (Dobyns, Doughty, and Lasswell 1971), appeared about a decade after the CPP saw the transition of power to the Vicosinos, and it was unqualified in its praise for the intervention. In stark contrast, years later William W. Stein offered an exhaustive deconstructionist excursion into the modernity project in Vicos, which appeared first in Spanish (2000) and then in English (2003). Stein, among the cohort of Cornell graduate students who studied with Allan Holmberg, had carried out doctoral research in a community not far from Vicos; he later turned his attention to Vicos through research in the Cornell archives as well as in the community. Before anthropology’s epistemic crisis of representation in the 1980s, Stein had already become a strong critic of the CPP’s objectives and claims, based on his reading of Marx and, later, Derrida to reinterpret the dynamics of culture and power in Vicos.4

One more work I want to mention here is quite distinct, authored by the “Comunidad Campesina de Vicos” (2005) with the assistance of Florencia Zapata. Over several years, Zapata worked with the Vicosinos to prepare an oral history of their community by means of wide-ranging interviews on community history, daily life, work, identity, language use, education, health, beliefs, cultural practices, and concerns for the future. Reference to the community’s past relationship with the CPP, recalled particularly by elders, reveals the ambivalence and uncertainty of many about how the project shaped the course of their lives. Some expressed gratitude, but others recalled Cornell as simply another hacendado, or patrón (hacienda owner). This oral history is an invaluable contribution to what we know of the community and of the subjectivity of Vicosino men and women today.5

Another edited collection came out decades after the CPP had pulled up stakes in Vicos, as an assessment of fifty years of applied anthropology in Andean Peru, with Vicos as the model (Greaves, Bolton, and Zapata 2011).6 A variety of assessments appear in this collection, from the familiar testimonials to the project’s success, to a critical appraisal of the CPP as product of the US Cold War strategy and a discussion of the tensions that manifested within the community and among personnel.7 Yet there is no editorial effort to engage these evident differences, and readers are left to draw their own conclusions. It is worth noting the two chapters that comprise the final part of the book, “Vicos Today.” This follows a dozen chapters on remembering and evaluating the Vicos Project, two chapters comparing Vicos to other applied anthropology projects, and another that considers the migration alternative favored by a growing number of Peruvians. Given the past gender politics surrounding the project, it is hard to overlook the fact that these are the only chapters in the anthology by women, Billie Jean Isbell (2011) and Florencia Zapata (2011), who played key roles at Cornell University in bringing attention back to Vicos. They led initiatives to launch the “Vicos: A Virtual Tour” website;8 host a 2006 conference at Cornell, to which a number of us who had conducted research in Vicos and several Vicosino men were invited to participate; repatriate thousands of photographs taken in Vicos; and carry out the oral history project in the community. Their contributions balance the volume with observations concerning Vicosinos in the present context and are among the few that offer even brief attention to gender.

In her chapter, Zapata quotes several passages from the oral histories she gathered just over a decade earlier that corroborate what I found in the archives regarding Vicosinos’ views of the importance of both men’s and women’s work in the hacienda community. For example, a Vicosino man recalled that during pre-CPP times, “on the hacienda neither women nor men were idle; everyone had his or her own tasks, men as well as the women.” Another man commented, “The landlord exploited us a lot. . . . Like a contractor does now, just like that, they made us work fourteen hours, all the same, men and women” (Zapata 2011: 325–26). Opinions differed over the impact of the CPP, with one man proudly stating that with Cornell’s arrival, Vicos was “liberated from the patrones” (Zapata 2011: 326), and another remembering negative impacts, such as the introduction of chemical fertilizer and what he perceived as the use of Vicosino women and men as “servants” to the CPP (Zapata 2011: 328).

Schoolgirls playing on a tractor in Vicos, 2011. Photo by author.

The brief introduction and conclusion to the collection edited by Greaves and colleagues do not do justice to the diversity of views presented or to the unresolved questions and disagreements laid out in the volume. Concerning gender and my past work specifically, I was interested to find in the introduction a passing remark in a listing of twenty “issues and queries”: “The project’s inclusion or exclusion of the women of Vicos has been debated (e.g., Babb 1980a). Different authors have reached different conclusions. What is a fair assessment?” (Greaves and Bolton 2011: x). Unfortunately, the question was never addressed; although my work was one of just a half dozen citations in the introduction, there was no further discussion of gender. A useful contrast is provided in a chapter of the volume that considers the case of Kuyo Chico, another important but less-celebrated community development project in Peru that began just a few years after the Vicos Project. Jorge Flores Ochoa (2011) offers fairly extensive remarks about ways that this project drew women into literacy classes and helped them gain voting rights; he notes failures as well, including the introduction of urban cookstoves that were not suitable for women who customarily sat while cooking. Such a gender-conscious approach might have usefully informed the Vicos Project as well.

Women playing soccer in Vicos, 2015. Photo by author.

Over time, I have come to view the avoidance of the gender question in discussions of the Cornell-Peru Project as part of a broader reluctance to take seriously those critics who would decolonize the knowledge surrounding the CPP. Generally, the notion has been that the critics suffer from “intellectual hubris” and would rather issue critiques than make a positive difference through their work.9 Yet, certainly by now there have been enough sustained critiques within anthropology coming from both northern and southern perspectives, as well as from areas that have been the recipients of even the best-intended development interventions, that anthropologists must pay heed. Efforts to decolonize knowledge and practice do not have to mean a failure to act or to support initiatives that local populations desire, and in fact these intellectual efforts frequently go hand in hand with social-movement-based activism. We need only recall the individuals discussed in this book’s introduction who have called for attention to the coloniality of power, including Quijano, Mignolo, Escobar, and Lugones, to recognize the deep commitment of these scholars to a more equitable world.

My critique of gender relations in Vicos during and after the project seemed to strike a particularly sensitive nerve. After the first publication of my Vicos monograph as part of a working paper series, my advisor sent copies to a number of people, including several who had been part of the CPP. In December 1976, one former CPP member, Henry Dobyns, wrote a five-page, single-spaced letter to my advisor (which the latter passed along to me) protesting that...

Table of contents

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- Introduction: Rethinking Gender, Race, and Indigeneity in Andean Peru

- Part I. Gender and Rural Development: The Vicos Project

- Part II. Gender and the Urban Informal Economy

- Part III. Gendered Politics of Work, Tourism, and Cultural Identity

- Conclusion: Toward a Decolonial Feminist Anthropology

- Notes

- References

- Index