- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

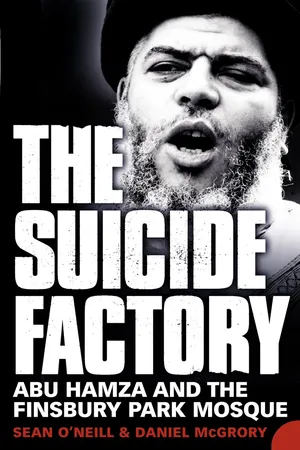

Two veteran journalists tell the inside story of convicted hate-monger Abu Hamza, his infamous Finsbury Park Mosque and how it turned out a generation of militants willing to die – and kill – for their cause…

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Suicide Factory by Sean O'Neill, Daniel McGrory in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & American Government. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Rise of Abu Hamza

1

Mostafa

‘We are all under the feet and the heavy boots of the kuffar [unbeliever].’

ABU HAMZA

The young Egyptian held the sheet of paper in both hands and, in his heavily accented English, read the words in front of him carefully: ‘I, Mostafa Kamel Mostafa, do solemnly and sincerely affirm that 1 will be faithful and bear true allegiance to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, Her Heirs and Successors, according to the law.’

Mostafa then signed the official form bearing the same pledge; his signature was formally witnessed by his solicitor and the document placed in the out-tray to be posted to the Immigration and Nationality Directorate of the British Home Office.

Just ten days later a certificate of naturalisation, declaring him to be a citizen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, dropped through the letterbox of Mostafa’s London council flat.

For the man who would become known as Abu Hamza al-Masri – possibly the most hated man in Britain and someone who would angrily despise British values – this was quite an achievement. Citizenship of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland was a goal he had pursued almost from the day he stepped off a flight from Cairo seven years before.

Abu Hamza had accomplished his aim with a display of ruthless and cynical dishonesty. Had his applications for refugee status been properly scrutinised by immigration officials, he could have been deported from Britain as an illegal immigrant and a fraudster long before he caused the trouble that he went on to stir up. Those investigations were never undertaken. Instead, on Tuesday, 29 April 1986, he swore allegiance to the Crown and won the right to stay in Britain for ever.

Ironically, he took that oath of allegiance as he was on the cusp of his conversion to a brand of political and religious fanaticism that would lead him to regard his adopted country as a godless, decadent land whose Queen deserved the sword rather than his allegiance. England, he became fond of proclaiming, was ‘a toilet’.

But Abu Hamza, the fanatical preacher of hatred, was a completely different person from Mostafa, the twenty-one-year-old student who disembarked at Heathrow airport on 13 July 1979. Tightly clutching his new Egyptian passport, number 172167, issued in Alexandria less than a fortnight before, he arrived in Britain in the middle of a year of revolutionary change. Margaret Thatcher had been swept into Downing Street, heralding an era of right-wing free-market radicalism that would shatter Britain’s post-war political consensus. The most feared terrorist organisation of the day, the Provisional IRA, struck that summer at the very heart of the British establishment, blowing up Lord Mountbatten, a senior member of the royal family, as he pottered around in a boat off the west coast of Ireland. In Europe, Pope John Paul II toured his native Poland, drawing massive crowds and throwing down the gauntlet to Eastern Bloc communism. On the other side of the world, Sandinista guerrillas seized power in Nicaragua and set about creating peasant socialism in America’s backyard.

But the changes that would have the longest-lasting global impact were happening in the Muslim world that Mostafa was leaving behind. 1979 began with the Shah of Iran fleeing into exile in the face of the modern world’s first Islamic revolt, and Ayatollah Khomeini returning to Tehran to seize power. The year drew to an end with the mighty Red Army of the Soviet Union pouring into Afghanistan to shore up its puppet government. The events that followed in poverty-stricken Afghanistan would change the world by reviving the Islamic concept of physical jihad in defence of the Muslim religion and lands. They spawned not just war without end for the Afghan people, but the brand of global terrorism that would be propagated by Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaeda.

Such things could not have been further from the mind of the young Mostafa Kamel Mostafa when he left his family’s comfortable middle-class home in Alexandria to travel abroad for the first time. There was a fashion among young Egyptians that year for visiting London, and almost from the moment he arrived, he wanted to stay. Although he was three years into a five-year degree course, he decided to abandon his engineering studies at Alexandria University. A powerful incentive for staying in England was the chance to avoid national service in the military back home.

He was a powerfully-built young man with a thick mop of curly hair, golden brown skin, an infectious smile and a mischievous twinkle in his eye. London offered things he hankered after more than a degree in engineering and years in the army – most especially women and wealth.

‘He had this huge chest, huge broad shoulders and big biceps, he had awesome genetics,’ remembered a friend. ‘He just had to look at a weight bar and he’d put on more muscle. He wore jeans and T-shirts and usually had a gold chain around his neck. He was cool and, yes, he was a womaniser – he was an Egyptian after all, what do you expect?’

Although his one-month visitor’s visa specifically ruled out working, the young man who would later be known as Abu Hamza quickly found a job, and he liked the feel of English pound notes in his pocket. A month after his arrival he applied to extend his stay by another month. Permission was granted without question, on the same ‘no work’ condition that he – like many others – was blissfully ignoring.

‘He was just like the rest of us,’ remembered Zak Hassan, another of the five or six hundred young Egyptian men having a youthful adventure in London that year. ‘We used to hang around in coffee shops in Queensway to talk and chat and eat. Everyone wore jeans, no one had a beard and nobody talked politics or religion, it wasn’t an issue any of us was interested in. Abu Hamza sat in the corner and joined in with everybody else. We talked about work, women and football. We were nearly all supporters of Al Ahly, Cairo’s biggest team, who play in red. So a lot of us started supporting Liverpool, because they played in red and they were the team of the moment in England. We were just ordinary young men looking for work. At night a lot of us went to pubs, not to drink but to chat up girls. But the priority was work. We had no families to support us, no mothers to go back to, so we had to earn money to rent our rooms and have enough food to eat.’

One of the future Abu Hamza’s several jobs was as night porter in a bed and breakfast hotel in Gloucester Place, not far from Paddington rail station. These establishments were often more hostels than hotels, with most of the residents living in cramped conditions as they waited to be housed in council accommodation. Here, in the spring of 1980, he met Valerie Traverso, a single mother of three young children who was pregnant by Michael Macias, her first husband, from whom she had recently separated.

Valerie, who was twenty-five at the time, felt an immediate attraction to the young Egyptian, and her feelings seemed to be reciprocated. He was a hunk, he paid her attention, and he made her laugh. She remembers his ‘nice, big hands’, his eyes and his coffee-brown skin; as a single parent, down on her luck, Valerie was flattered that the exotic young foreigner was interested in her.

But Abu Hamza’s interest in Valerie seems to have been more than just a physical one. He was an illegal immigrant. He had not renewed his visitor’s visa when it expired the previous September. Instead he blended into the black-market world of cash-in-hand casual work. Valerie’s pregnancy presented him with an opportunity which he could exploit. If he could marry her and persuade her to let him claim that he was the father of her child, his immigration status would be vastly improved.

He acted quickly. As night porter, Abu Hamza allowed Valerie to use the staff kitchen in the hotel to warm up milk for her toddler son. One night, not long after they first met, she was alone in the kitchen when he came straight up to her and kissed her passionately. He was direct and physical, and she found him hard to resist.

‘He made the first move,’ she said. ‘I’m not the sort of person to do that kind of thing. It was there in the kitchen. I was surprised, I didn’t think it would happen so soon because I hadn’t long come out of a long relationship and was surprised with myself more than anything. Things moved pretty fast. We became very close very quickly. But he was also a romantic man, quite tender and softly spoken. We laughed a lot.’

The sex was good, but when Abu Hamza suggested they get married, Valerie turned him down. He had proposed as they sat in the reception of the Four Seasons Hotel, Queensway – another of his places of employment – late one night. She was four years older than him, and felt that she would not be able to trust him.

There were lots of women after the young night porter, drawn by his rugged looks and ready charm. Valerie did not trust Abu Hamza to stay faithful when there were so many other women who would not encumber him with a brood of young children. Other women who lived or worked in the hotel were interested in him; one in particular, called Tracy, made no bones about the fact. She was always hanging around the reception desk or butting in when Valerie was chatting to her new man.

Regardless of what Tracy wanted, Abu Hamza had set his sights on Valerie. He persisted with his marriage proposal, and it was not long before she relented. They were married in Westminster Register Office on 16 May 1980, just ten months after he had arrived in Britain. Around twenty guests were present; acquaintances rather than friends. None of his family attended. His father was an Egyptian navy officer and his mother a schoolteacher and later a schools inspector. They were disappointed that he had decided to stay in Britain rather than return to Alexandria to complete his degree course.

Valerie has repeatedly insisted that the marriage was the result of a genuine love affair. But she can hardly have been unaware of Abu Hamza’s immigration status. Significantly, when they wed she spelt her name on the marriage register incorrectly, as ‘Traversa’ and not ‘Traverso’. At the time of her marriage to Abu Hamza she and her first husband were separated but not divorced. They did not divorce until July 1982. Her marriage to Abu Hamza was bigamous. Valerie has protested in interviews since that there was no intent on her or Abu Hamza’s part to marry illegally. It was a mix-up, a simple confusion. But just a few months later a second false entry was being made on an official register.

On 26 September 1980, Valerie gave birth to the child with whom she had been pregnant when she met Abu Hamza. Her daughter was born in the South London hospital in Clapham. Within four days of the baby’s birth, Abu Hamza instructed lawyers to write to the Home Office stating that the young Egyptian immigrant had married an Englishwoman and become a father. He had been living in Britain illegally, but now that he had a wife and child here he wanted to ‘regularise’ his stay. He wanted to remain in the country indefinitely.

Such a claim would have to be supported by documentary evidence, namely marriage and birth certificates. The wedding document the couple already had. On 22 October the birth of Valerie’s daughter was recorded at the office of the Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages in Lambeth. The child’s name was entered as Nahed Donna Mostafa, and the name of her father was registered as Mostafa Kamel Mostafa. He gave his birthplace as Egypt and his occupation as ‘labourer’. Abu Hamza signed the register ‘Mostafa’. The name of the child’s mother was recorded as Valerie Olga Macias – using the surname of her first husband, to whom she was still married, albeit bigamously. She gave her maiden name as Traverso – spelling it correctly on this occasion. Beside Mostafa’s signature, the name ‘V. Macias’ was signed.

The marriage of Abu Hamza and Valerie Traverso was not legal. It appears that the registration of Valerie’s daughter’s birth was also carried out illegally. Valerie insists to this day that she was pregnant when she met Abu Hamza – she is ‘150 per cent on that’. If that is true, the birth certificate for the child, which states that he is the father, is a fraudulent document. Now registered as both a husband and a father under British law, Abu Hamza had a strong claim to be allowed to live legally in Britain. But his claim was based on a double deception.

Abu Hamza seemed firmly set on the path to citizenship, but it was not to run as smoothly as he had hoped. On the night of 12 December 1980, police carried out a series of raids on clubs in Soho, the centre of London’s sex industry. They were looking for unlicensed premises and illegal workers from overseas. At Jan’s Cinema Club on Archer Street, a seedy porn-and-prostitutes joint owned like much of Soho at the time by a Maltese family syndicate, officers arrested a number of people, including the Egyptian doorman.

Abu Hamza’s muscular frame had made him ideal for work as a bouncer. It was relatively well-paid, strictly cash, no questions asked, and involved little more difficult than warding off drunks and protecting the club’s strippers and hostesses from the over-enthusiastic attentions of some of the clientele. The clubs operating on the wrong side of the law always employed security to keep the punters in order and reduce the chances of attracting any police attention. Jan’s Cinema Club was shut down, albeit temporarily, and the employees rounded up. The doorman was quickly identified as an illegal immigrant and charged.

The following February he was brought before Great Marlborough Street magistrates’ court, where past defendants have included Oscar Wilde and Mick Jagger. As Mostafa Kamel Mostafa he pleaded guilty to the offence of overstaying his visitor’s visa by fifteen months. But he had an effective sob story of love, marriage and fatherhood to tell the court. Furthermore, the magistrates were told, the doorman had already applied to ‘regularise’ his immigration situation and the file was being considered by the Home Office. On 3 February 1981 the magistrates handed down a conditional discharge and sent him on his way. Six months later, Abu Hamza was granted official permission to stay in Britain until May 1982 on the grounds of his marriage to a citizen. His request for permission to stay indefinitely was kept under review.

No one could have known it at the time, but the Great Marlborough Street bench had been presented with the opportunity to deport a man who would become one of the most potent recruiters for a brand of worldwide terrorism that was then unimaginable. Much has happened since: the grand old courthouse has become a fashionable hotel, restaurant and bar; Jan’s Cinema Club is long gone and Archer Street is down to its last sex shop; and Mostafa the doorman somehow transformed himself into a designated international terrorist.

Valerie Traverso’s life has changed greatly too. She has married two more husbands, but still denies adamantly that Abu Hamza used her as his fast track to British citizenship. She has insisted in interviews that they were in love, and that the relationship was cemented in early 1981 when she fell pregnant by him. Her then husband, she said, was ‘thrilled to bits’. When their son Mohammed was born in October 1981, Abu Hamza was every inch the doting father. ‘You couldn’t fault him with the kids. He took them everywhere, looked after them, provided us with money,’ she told The Times in 2006. He was ‘determined to be a brilliant father and a good husband’, she said in the Mail on Sunday in 1999. Family snapshots from the time seem to support her story. They show Abu Hamza, dressed in the fashions of the time, proudly holding his baby son or rolling about on the carpet, playing with the boy.

But the image of the family man was hard to maintain. Abu Hamza’s work in Soho took him to brothels and bed shows, and onto streets ripe with temptation for a young male. The working girls were often grateful for the protection of their musclebound guardian. Abu Hamza began at least one affair. He has always been coy about this period of his life, bemoaning the men who came ‘to fantasise’ at these places, but adding: ‘I was a very undisciplined Muslim.’

Back home, busy with nappies and night feeds and waiting for the scrape of his key in the lock each night, Valerie became increasingly suspicious of her husband’s nocturnal activities. He seemed to be arriving later and later at their flat in Putney, south-west London. And he would not tell her where he had been or, when he left home, where he was going. Eventually, after a noisy confrontation, he admitted that he had had an affair with a girl he met through the club. The Sun newspaper has reported that her former husband’s lover was a prostitute.

This confession was to be one of the key turning points that would put Abu Hamza onto the path of radical Islam. Until that moment he had shown little interest in being a Muslim. The Egypt he grew up in was Muslim in name but secular and nationalist in much of its outlook, although he followed some traditions, such as having men and women dine separately whenever his friends visited.

But when Abu Hamza admitted the affair, Valerie threatened to leave him. He could not afford to be deserted. His immigration status was not secure. ‘I told him that things had gone too far and I was leaving,’ she said. ‘He responded by saying that he would change and he would dedicate himself to Islam. He swore that he would never do it again. He was going to be religious, he was going to pray and ask for God’s help.’

Valerie, who had been born into a family of Spanish Roman Catholics, decided that she too would investigate this religion with her husband: ‘We would sit and read it [the Koran] together. When he started to study, I started to study. I started to learn Arabic. I tried to learn to write it too but it was pretty tough.’

The alien language was not the only tough aspect of her conversion. Walking on the street in Putney one day, Valerie and a friend were attacked because they were wearing the hijab, or headscarf. ‘A few lads came along, jumped out of their car and pulled our scarves off our heads and threw them in the road,’ she said. ‘Our friends were very troubled. They had wreaths put outside their door, their car was attacked and their children were bullied at school. My reaction was to stop wearing the hijab. Mostafa asked me why I had stopped. I told him it was my own choice, that I had started wearing it and that I could stop wearing it if I so wished.’

Despite the prejudice his wife had encountered, Abu Hamza was still keen on staying in Britain, and continued to pursue a resolution of his immigration situation. In April 1982 the Home Office informed him that he had to extend the validity of his Egyptian passport before it could consider his case further. The passport had expired, rendering him in a stateless limbo. He responded in June, claiming that the Egyptian embassy in London had refused to renew his passport because he was a young man of army age. He was supposed to return home for national service. Two months later, perhaps because the threat of conscription was considered oppressive, the Hom...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Chronology

- Prologue

- Part I: The Rise of Abu Hamza

- Part II: His Chosen Ones

- Part III: The Reckoning

- Epilogue: The Legacy

- Index

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Copyright

- About the Publisher