1

Introduction

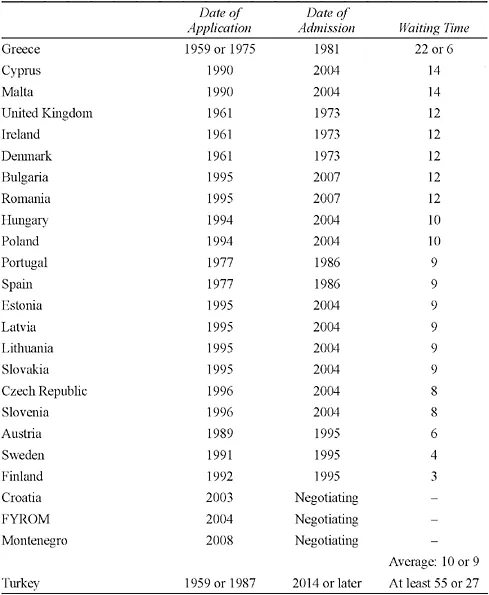

It has been fifty years since Turkey applied for associate membership of the European Economic Community (EEC) on 31 July 1959.1 As of 2009, Turkey is still not a member of the – now – European Union (EU), and by even the most optimistic estimates, it cannot become a member before 2014.2 Being the next applicant after Greece – who lodged its application to the EEC only a few weeks before Turkey, but who became a member in 1981 – Turkey’s long stay in the waiting room deserves closer examination. It is true that decades are like days in the lives of countries. It is also true that admission to a family of states may take a long time. For instance, among the states of the United States it took 40 years for Arizona, and 62 years for New Mexico to achieve their statehood status.3 In the case of the EU, the ‘average waiting time’ is around 9 or 10 years, whilst Turkey will have waited 55 or 27 years if it manages to become a full member in 20144 (see Table 1.1.)

This considerably long waiting time of Turkey has a few important connotations:

It is not good enough for things to be planned – they still have to be done; for the intention to become a reality, energy has to be launched into operation.

Walt kelly (American cartoonist, 1913–1973)

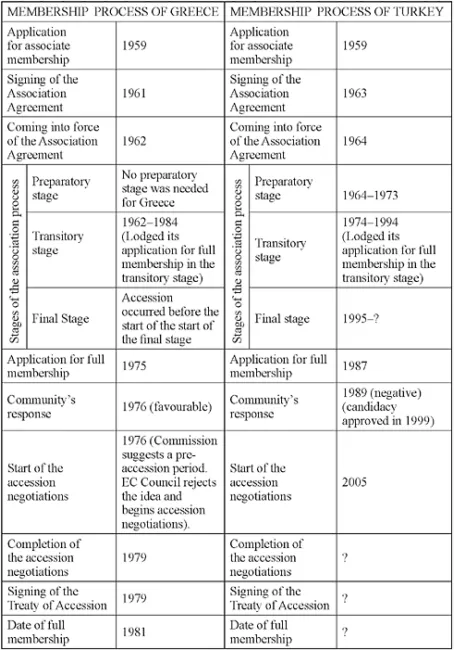

Since the coming into force of the Ankara Agreement in 1964, Turkey–EU relations have followed a certain schedule: the schedule that was put forward by the Agreement itself. Accordingly, the relations would go through three stages (Art. 2 of the Agreement): (i) a preparatory stage, (ii) a transitory stage, and (iii) a final stage. The final stage would possibly culminate with Turkey’s full membership (Art. 28).

This schedule has been duly followed to this day. Having established a customs union with the EU, Turkey is now in the final stage, engaged in accession negotiations with the EU. Thus, prima facie it may seem that there has been no delay in Turkey–EU relations. However, in reality a series of delays stretched out each of these stages to its limits. Together with the delay between the application in 1959 and the coming into force of the Ankara Agreement in 1964, the completion of Turkey’s membership process is taking much longer than

Table 1.1 Waiting times of the EU members and applicants

expected. A comparison between the membership chronology of Greece and that of Turkey may give a better idea about the prolongation in the case of the latter (see Table 1.2).

The delay in each of these stages had its own reasons; sometimes it was Turkey that dragged its feet, or actually asked for time extensions, and sometimes it was the Union or some of the Member States that insisted on procrastination. As partners in crime, Turkey, the EU and the Member States did not put enough energy into the plan, and pushed it into oblivion.

The contributors to this volume help us understand the reasons behind thisfifty-year delay.

Table 1.2 A comparison between the duration of the stages of the membership processes of Greece and Turkey

Delay always breeds danger, and to protract a great design is often to ruin it.

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (Spanish novelist, poet and playwright, 1547–1616)

The prospect of Turkey’s admission to the European Union bears greater importance than the accession processes of many other European states. If Turkey becomes a member of the Union, for both Turks and Europeans this will be the realisation of an age-old idea first contemplated by William Penn.5 This membership will mean the inclusion of a country with a 99 per cent Muslim population in Europe, heralding the peaceful coexistence or rather the blending of Christianity and Islam, of Europe and Asia as well as of the East and the West. It was with this vision and enthusiasm that Walter Hallstein, a Christian Democrat and the then President of the Commission of the EEC, uttered the following words on the occasion of the signing of the Ankara Agreement on 12 September 1963:

However, at the 27 September 2006 debates of the European Parliament, Hartmut Nassauer another Christian Democrat and the then vice chairman of the Group of the European People’s Party (Christian Democrats) and European Democrats (EPP-ED)7 claimed that ‘[i]t [was] inconceivable that Turkey should become a Member State of the EU without facing up to the facts of history’.8

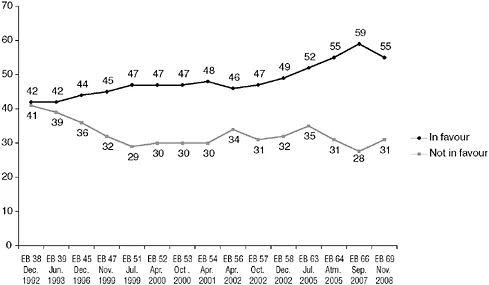

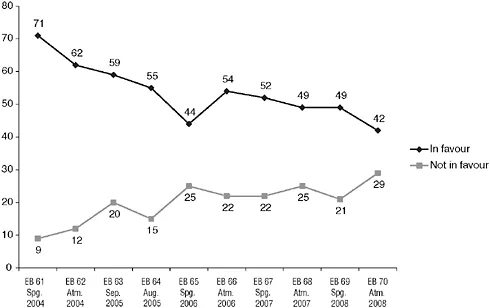

The change of attitude from September 1963 to September 2006 is an indicator of a deterioration that has evolved over a long period of time. This deterioration is becoming established in the minds of the European public and the number of EU citizens who are against Turkish membership of the EU is steadily increasing (see Figure 1.1).

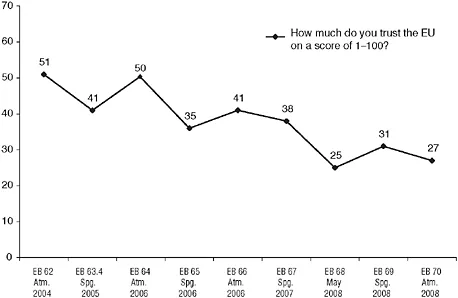

This fifty-year period has had its negative influence on the minds of Turks as well, and now ‘Turkey seems to have every reason to turn its back on the West’;9 Turkish public-support for EU membership has declined drastically (see Figure 1.2). In a similar vein, Turkish people’s trust in the EU is also in decline (see Figure 1.3).

This is a delay that has bred the danger of deterioration of the relations between Turkey and the EU, and imperilled the great design of anchoring Turkey to Europe. The peoples of both parties have been aloof from each other for some time.

Having this decline in mind, the contributors to this volume help us understand the costs of this fifty-year delay for Turkey, for the European Union as well as for intercivilisational dialogue.

Delay is the deadliest form of denial.

Cyril Northcote Parkinson (British naval historian and author, 1909–1993)

Since the second half of the nineteenth century, Turkey has turned its face towards the West. With the kemalist revolution, many parameters of Turkish society, from the alphabet to clothing, were changed in a dramatic and almost irreversible way. Politically, Turkey allied with the West by becoming a NATO member and a candidate for membership of the EU, and thus alienated itself from its Eastern neighbours and especially from Islamic countries. However, Turkey’s expectations went unfulfilled.