![]()

Part I

Threat to labour standards?

![]()

The Irish experience with post-2004 labour mobility and the regulation of employment standards

Torben Krings, Alicja Bobek, Elaine Moriarty, Justyna Salamońska and James Wickham

Introduction

The Irish migration experience at the beginning of the twenty-first century was quite extraordinary. Within the space of a decade, the country’s share of foreign-born population doubled to over 17 per cent (OECD, 2011, p. 385). In the context of an open labour market and an unprecedented economic boom, Ireland attracted large-scale migration from the new EU member states (NMS). Since EU enlargement in 2004, more than half a million citizens from the NMS, in particular from Poland, have arrived in the country. While this migration contributed to economic growth during the boom years, it also raised concerns about social dumping and a ‘race to the bottom’ in relation to employment conditions. Although the boom came to an abrupt end in 2008, compliance with wage agreements and employment regulations remains a significant challenge in the ‘post-Celtic Tiger’ era.

This chapter explores the impact of recent mass migration upon labour standards in Ireland. It focuses specifically upon two employment sectors – construction and hospitality – that have been major destinations for NMS migrants. Drawing upon qualitative interviews with Polish migrants and Irish firms,1 the chapter shows that employers have frequently used migrant labour as a cost-cutting strategy in what may be classified as instances of social dumping. However, these practices have varied, depending on the regulatory environment and the role of unions in each sector. In construction, where unions are a powerful force, social dumping mainly involved the breach of collective agreements through subcontracting arrangements at the more informal fringes of the sector. In hospitality, by now largely de-unionized and characterized by an informal work culture, social dumping was often synonymous with non-compliance with existing employment regulations.

More generally, both sectors experienced growing casualization of employment in the context of social dumping practices. While this was primarily an employer-driven strategy, migrants did not necessarily perceive the casualized employment relationship as a disadvantage, especially when the job was seen as only transitional and comparisons were made to Poland. However, the longer they stayed in the country, the more assertive migrants became about their employment rights, sometimes assisted by the unions. While some migrants were able to negotiate better working conditions during the boom years, the 2008 recession fundamentally transformed the labour market situation in Ireland. In times of rising unemployment, the bargaining position of employers strengthens as domestic and foreign workers alike struggle increasingly to meet growing demands for more flexibility in pay and working practices.

The chapter proceeds as follows. It first outlines the context of mass migration to Ireland and subsequent attempts to re-regulate the labour market. It then presents evidence from the two sectors to illuminate the experiences of migrants and the strategies of employers at the micro level. The chapter concludes by discussing the future of labour standards in post-boom Ireland, which continues to host a substantial migrant workforce.

Mass migration in a ‘gold-rush’ labour market

The context of large-scale migration to Ireland from the NMS and elsewhere was the ‘Celtic Tiger’ boom in the 2000s. Whereas in the 1990s the upswing was driven by foreign direct investment and high-tech manufacturing (Barry, 2007), the main driving force in the 2000s was the construction sector. An unprecedented building boom not only created one of the worst property bubbles in recent history but also generated a huge demand for additional labour. In the later boom years, this demand was largely met by mass migration from Poland and other NMS as the Irish labour market effectively ceased to be a ‘national’ labour market in the context of EU enlargement.

Unlike the ‘guest-worker’ migration of the 1960s and 1970s, this East–West mobility was not an organized form of labour migration but a free flow of people and information. For potential migrants in Poland, Irish job offers were visible on the Internet or communicated through informal social networks (Komito and Bates, 2009). New transport technologies made Dublin easier to reach from Warsaw than Warsaw from many provincial Polish towns. New arrivals could be fairly certain to find employment, while employers could be quite confident to have access to new labour. In short, the Irish ‘gold-rush’ labour market was characterized by an apparently infinite demand for and a seemingly infinite supply of new labour, whereby demand and supply mutually reinforced one another and led to an explosion of new jobs.

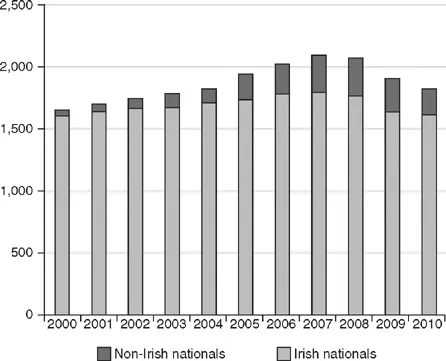

As the territorial boundaries of the Irish labour market became permeable, the composition of the workforce changed. In the 1990s, the vast majority of new jobs were taken up by Irish nationals. Ireland’s late baby boomers of the 1970s were entering the job market, more women were looking for work and Irish emigrants were returning. However, the picture changed in the 2000s. Especially from 2004 onward, two-thirds of new jobs were taken up by NMS nationals.2 In other words, in the final years of the boom, employment growth was largely driven by mass migration coming mainly from Poland, but also from Lithuania, Latvia and Slovakia. However, almost by definition, a ‘gold rush’ does not last forever. In 2008, the boom came to an abrupt end as Ireland was hit by a sharp recession and a concomitant decline in employment (see Figure 1.1).

At the time of EU enlargement in 2004, the unemployment rate in Ireland was quite low, at around 4 per cent, which is usually regarded as being close to full employment. The need for additional labour thus seemed self-evident in the light of a fast-rising number of jobs and vacancies in the ‘gold-rush’ labour market. However, it is worth bearing in mind that mass migration occurred at a time when the employment rate in Ireland was ‘only’ 66 per cent and as such below the ‘Lisbon target’ of 70 per cent set by the EU for its member states in 2000. In other words, for Ireland, importing labour was de facto preferable to mobilizing all the potential ‘indigenous’ workforce. This perhaps was not all that surprising given that liberal market economies are more prone to importing labour to compensate for skill and labour shortages (Menz, 2009). Whereas more ambitious active labour market programmes would have required more strategic and long-term planning, the boom years were characterized by instantaneous growth and short termism, which to some extent encouraged dumping practices, especially in the construction sector.

In relation to enlargement, there were particular concerns among many old EU member states that labour mobility from the NMS could lead to incidents of wage dumping and job displacement (Donaghey and Teague, 2006). However, in spite of the large-scale migrant inflows, Ireland did not experience major labour market dislocations. Its flexible labour market was able to incorporate the new arrivals to the workforce without undergoing major displacements or exhibiting the levels of segmentation that are characteristic of immigrant workforces in the Southern European countries (Schierup et al., 2006; see also Kahmann, Chapter 3, this volume). While wage growth may have been moderated in some less skilled occupations, employment opportunities for the domestic workforce have not declined in the context of recent migration (Barrett, 2010).

Figure 1.1 Total employment of Irish and non-Irish nationals aged 15 years and over (in ’000s) (source: European Labour Force Survey (Eurostat, 2013); data compiled by authors).

The flip side of Ireland’s flexible and fast-growing labour market was a weak enforcement of labour standards. Especially in the immediate aftermath of enlargement and Ireland’s opening up of its labour market, non-compliance with labour standards was quite widespread (Flynn, 2006; MRCI, 2006). However, since many such incidents occurred in non-unionized workplaces, they were initially not an issue of major concern for the Irish trade union movement. This began to change in 2004 when a multinational construction company, GAMA Construction, was found to be paying its Turkish building workers wages that fell well below the industry rates. Eventually, the Services, Industrial, Professional and Technical Union (SIPTU), Ireland’s largest union, became more actively involved and intervened on behalf of the migrant workers, many of whom were actually enrolled as members of SIPTU (Flynn, 2006).

If the GAMA case raised awareness about the plight of some migrants in Ireland, it was the 2005 Irish Ferries dispute (in many respects a paradigmatic example of social dumping) that captured the attention of Irish unions and the broader public. The decision of Irish Ferries to replace over 500 of its mostly unionized Irish staff with cheaper agency workers from Central-Eastern Europe in the name of ‘competitiveness’ sparked off huge public protests, culminating in a ‘National Day of Protest’ that saw around 100,000 people take to the streets in Dublin and other parts of the country. Although the protest marches organized by the Irish trade union movement had an inclusive outlook (‘Equal rights for all workers’), resentment towards migrants increased among some segments of the Irish public. There was particular concern about the impact of mass migration upon employment conditions (Brennock, 2006). To counter such tendencies and to prevent a segmentation of the workforce along national lines, the unions responded with a rights-based approach to ensure that ‘migrant workers have the same rights and protection as Irish workers’ (SIPTU, 2006, p. 21).

For the unions, besides efforts to put a greater emphasis on organizing migrants (see below), the social partnership process became the main forum for addressing issues such as labour market compliance. In negotiations for the 2006 partnership agreement Towards 2016, the unions eventually succeeded with their demand for a stronger enforcement regime, not least because the employer bodies were keen to maintain industrial peace and the continuation of the partnership process. Among the measures agreed on by the social partners was stronger protection against collective dismissals (so as to prevent an Irish Ferries scenario ‘on land’) and the establishment of a statutory agency for employment rights. Although the proposed Employment Law Compliance Bill has yet to be enacted – because employer groups began to resist some of the agreed measures, especially following the onset of the economic crisis (Doherty, 2011, p. 378) – the National Employment Rights Authority (NERA) was already established as an enforcement body in 2007. Since its inception, NERA has revealed relatively high rates of non-compliance with employment rights in sectors such as construction and hospitality that have a high proportion of migrants (NERA, 2009, p. 8). This situation will be illustrated below at the micro level by presenting evidence from a two-year qualitative panel study with a group of Polish migrants complemented by employer interviews.

Migrant employment in the construction sector: subcontracting and agency labour

In the first decade of the twenty-first century, Ireland experienced an unprecedented construction boom. Its main driving force was the expansion of domestic credit, leading to rapidly rising asset prices – a classic property bubble. As the sector burgeoned, construction employment skyrocketed: between the second quarter of 2002 and the same quarter of 2007, employment in this sector rose from 170,000 to 270,000 (CSO, 2011). After 2004 and the opening up of Ireland’s labour market, much of this increase came from mass migration (especially from Poland), which arguably contributed to sustaining the construction boom. Employment of Irish nationals also increased in those years, suggesting that inward migration was largely complementary to the domestic workforce (see Figure 1.2).3 As many Irish workers moved into semi-skilled job positions, there was a particular demand for less skilled construction labourers. At the same time, NMS migrants were also recruited for skilled trades occupations and, in smaller numbers, for higher skilled engineering positions. Much of the recruitment was quite informal, often relying on migrant...